ART CITIES: London-Danh Vo

Through a body of personal work inspired also by historical and political events, Danh Vo probes into the inheritance and construction of cultural conflicts, traumas, and values. When Vo was a child, his family fled Vietnam and settled in Denmark: their assimilation to European culture and the political events that prompted their flight are intrinsic to his artistic investigations.

Through a body of personal work inspired also by historical and political events, Danh Vo probes into the inheritance and construction of cultural conflicts, traumas, and values. When Vo was a child, his family fled Vietnam and settled in Denmark: their assimilation to European culture and the political events that prompted their flight are intrinsic to his artistic investigations.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo White Cube Gallery Archive

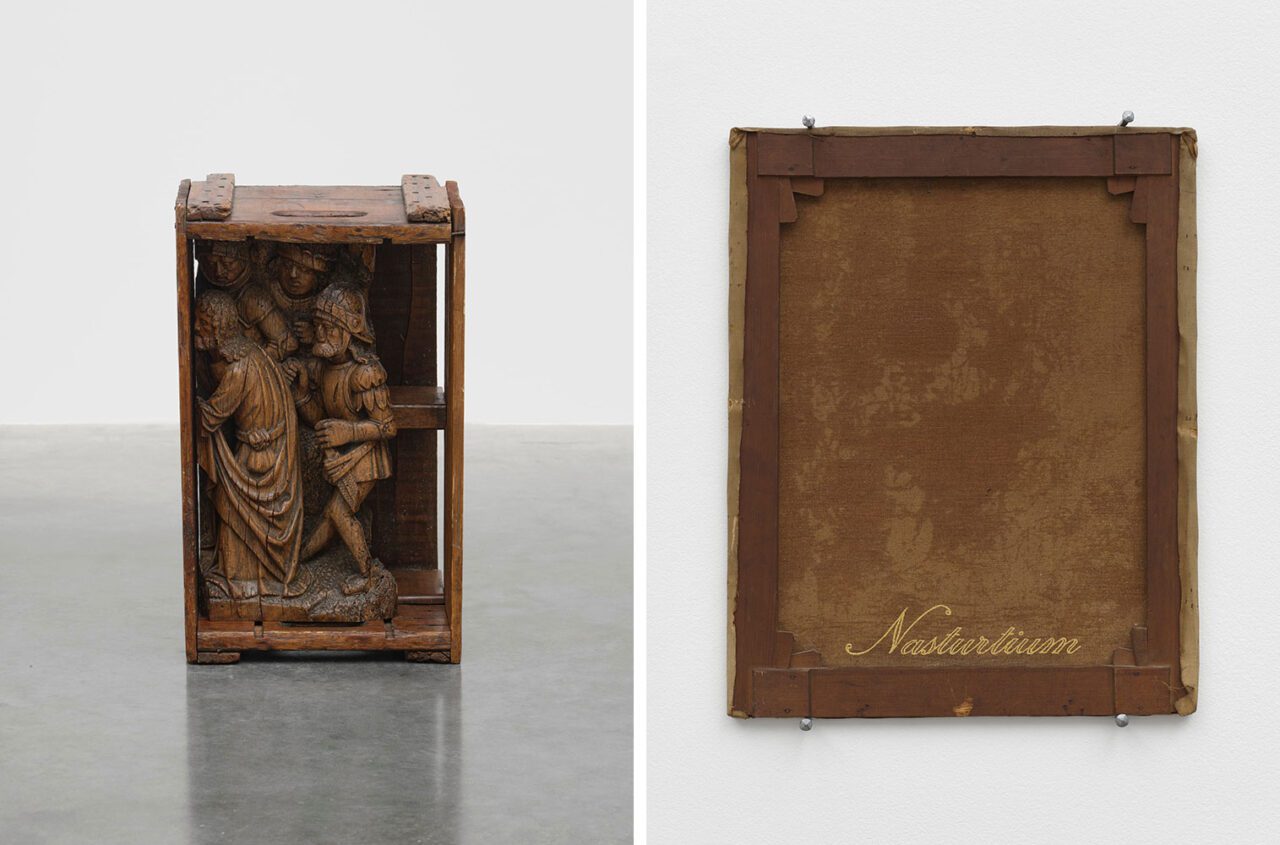

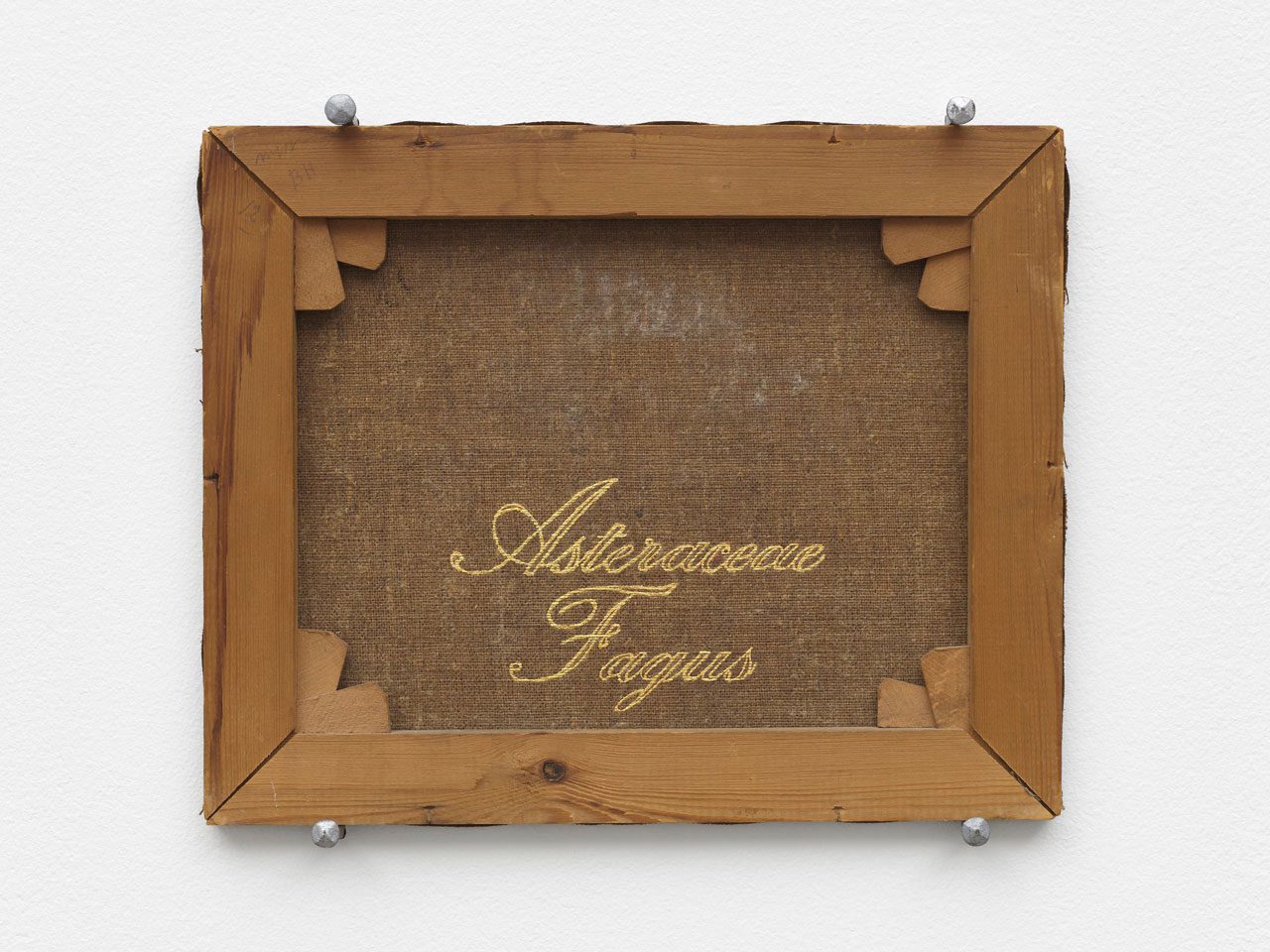

Dahn Vo’s work sheds light on the relation between the inseparable elements that shape our sense of self, both through collective history and private experience. Exhibiting objects based on the ready-made principle is a characteristic artistic strategy of Vo; through objects charged with symbolism that retains the sublimated desire and sadness of individuals and entire cultures, he examines how meaning changes with context. Vo’s work, enigmatic and poetic, deftly avoids didacticism as he explores the power structures behind liberal societies and the fragility of our nation-state notions. In his solo exhibition in White Cube Gallery Danh Vo, continues his exploration of power structures and their influence on both personal and collective identity. Vo’s last exhibition at the White Cube Gallery took place in the closing days of the 2020 US Presidential election, considered then the most consequential in history. It included a monumental depiction of the “13 colonies” flag that came to be seen as allegorical for the tensions of the time. Here, in the shadow of another such election, Vo’s found objects, oil paintings, bronzes and other works have a quieter quality, and consider how artistic labour finds ways to resist, adapt and survive no matter the political and social climate. In the ground-floor gallery, behind a provisional wall, a sculpture combining two fragments of ancient Roman marble is flanked by two paintings: Nancy Spero’s ”All Writing is Pigshit” (1969), which features a quote from the French poet and playwright Antonin Artaud, and a portrait of the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco by Leon Golub (1976). Vo makes temporary spatial interventions to shape corridors of light and shadow in the gallery architecture, including pinewood construction scaffolding on the ground floor, which partially obstructs both physical and visual access. In the niche of a barricaded stairwell, the artist has hung a bronze cast of a 16th-century Spanish figure of Christ crucified. Though the figure is missing its arms, casts of the hands of the artist’s father, Phung Vo, appear in their place. They hold glass tubes growing “Tropaeolum majus”, a red flowering plant whose name borrows from the ancient Greek word for ‘trophy’. Is Vo taking a Catholic father and using him to mutate a religious relic in the name of utility? While the artist sometimes teases this kind of cruelty, it is rarely more than a patina. Is this rather a way for Vo to remember the lines on his father’s palms? A way to remember his father? Staging a meeting of craft across time, Vo’s floral canvases – originally painted by Northern European female artists between the late 19th and early 20th centuries – were procured through auction and inscribed on their verso by Phung Vo with the Latin names of the depicted flowers. The canvases later journeyed to Thailand where artisans applied gold gilding to the calligraphic lettering. An enduring motif in Vo’s work, flowers carry a rich symbolic lexicon, variously embodying beauty and love, sovereignty and resilience. Many of these paintings took place in the context of related movements, such as Skønvirke in Denmark. In response to industrialisation, artists turned to an ornate beauty that could only be born from craft. As such, there was a strong emphasis on the dignity of labour. That the objects survive as contemporary art gives them an eerie politics: Vo’s layers build value and attraction, yet who exactly consented to this evolution? With Vo, such tensions between beauty, power and intimacy are key. Around the gallery, two vintage wooden crates are emblazoned with the Coca-Cola and Johnny Walker logos and respectively cradle a carved oak altarpiece and the torso of a wooden putto*. By splicing together these idiosyncratic objects the artist considers the persistence of iconographies – that brand names and religious narrative may be equally powerful tools of persuasion, each operating in their own way at the vanguard of colonial expansion. Two luxury-brand Rimowa suitcases housing priceless artefacts – the limbs of the aforementioned putto and a Gandharan schist relief – offer wry commentary on value paradigms. Contained within the suitcases, the objects evoke a range of associations, the travel souvenirs of the wealthy, globalised elite, or the clandestine routes of art smugglers. Rimowa pioneered aluminium cases renowned for the denting and scratches they pick up in travel. The company celebrates aluminium: ‘It changes! It evolves! It lives!’ This maxim also works, sometimes ironically, for any object with which Vo interacts. A suite of bronze sculptures cast from original East Asian stone-carved artefacts retain the distinctive marks of their casting process. Representing Hindu and Buddhist figures, the bronzes are exhibited from the behind, revealing abstract, hatched patterns made by looters who hacked and sawed the works from their stone edifices for sale to Western collections. The original works will travel to Vo’s gardens on his farm in Güldenhof near Berlin, where they will be allowed to age in nature. One of these bronzes was cast from a 17th-century wooden sculpture of St Catherine – the martyred saint and alleged muse of Joan of Arc. A black walnut bird feeder embedded into her verso side imbues the work with a new and unexpected purpose. This wood, a recurring element in Vo’s practice, was farmed by Craig McNamara, environmentalist and son of Robert McNamara, the US Secretary of Defense between 1961–68, known for his role in escalating the American War in Vietnam. Uniting the themes that have preoccupied his practice over the past decade, Vo’s curated realms are charged with restless histories and an endless chain of associations linking the objects within.

* A putto is a figure in a work of art depicted as a chubby male child, usually naked and very often winged. Originally limited to profane passions in symbolism, the putto came to represent a sort of baby angel in religious art, often called a cherub, though in traditional Christian theology a cherub is actually one of the most senior types of angel.

Photo: Danh Vo, Untitled, 2024, Bronze cast of 2nd–3rd-century Gandharan figure of Goddess Hariti and pinewood, Edition 2 of 6, Sculpture: 172 x 55 x 22 cm | 67 11/16 x 21 5/8 x 8 11/16 in., Installed: 40 x 175.5 x 55 cm | 15 3/4 x 69 1/8 x 21 5/8 in., © Danh Vo, Courtesy the artist and White Cube Gallery

Info: White Cube Gallery, White Cube Mason’s Yard, 25 – 26 Mason’s Yard, London, United Kingdom, Duration: 11/10-16/11/2024, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-18:00, www.whitecube.com/

Right: Danh Vo, Untitled, 2024, Oil on canvas, writing by Phung Vo, gilded in Thailand, 57 x 45.5 cm | 22 7/16 x 17 15/16 in., © Danh Vo, Courtesy the artist and White Cube Gallery

Right: Danh Vo, Untitled, 2024, Bronze cast of 7th-century Khmer figure of Durga and pinewood, Edition 2 of 6, Sculpture: 85 x 42 x 19 cm | 33 7/16 x 16 9/16 x 7 1/2 in., Installed: 96 x 65 x 19 cm | 37 13/16 x 25 9/16 x 7 1/2 in., © Danh Vo, Courtesy the artist and White Cube Gallery