PRESENTATION: Kazuko Miyamoto

Kazuko Miyamoto is an important protagonist of New York’s Lower East Side art scene, pushing the boundaries of Minimal Art by building bridges between Western art practices and her Japanese heritage. Miyamoto’s multilayered, radical works defy simple categorization and attribution: they find their starting point in Minimal Art, but go beyond its strict geometric abstraction. Her impressive string constructions—two- and three-dimensional works consisting of hundreds, sometimes thousands, of nails and cotton threads—as well as her later works made of twisted paper ropes and painted kimonos convey a strong, corporeal presence in space despite their ephemeral character.

Kazuko Miyamoto is an important protagonist of New York’s Lower East Side art scene, pushing the boundaries of Minimal Art by building bridges between Western art practices and her Japanese heritage. Miyamoto’s multilayered, radical works defy simple categorization and attribution: they find their starting point in Minimal Art, but go beyond its strict geometric abstraction. Her impressive string constructions—two- and three-dimensional works consisting of hundreds, sometimes thousands, of nails and cotton threads—as well as her later works made of twisted paper ropes and painted kimonos convey a strong, corporeal presence in space despite their ephemeral character.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Belvedere Archive

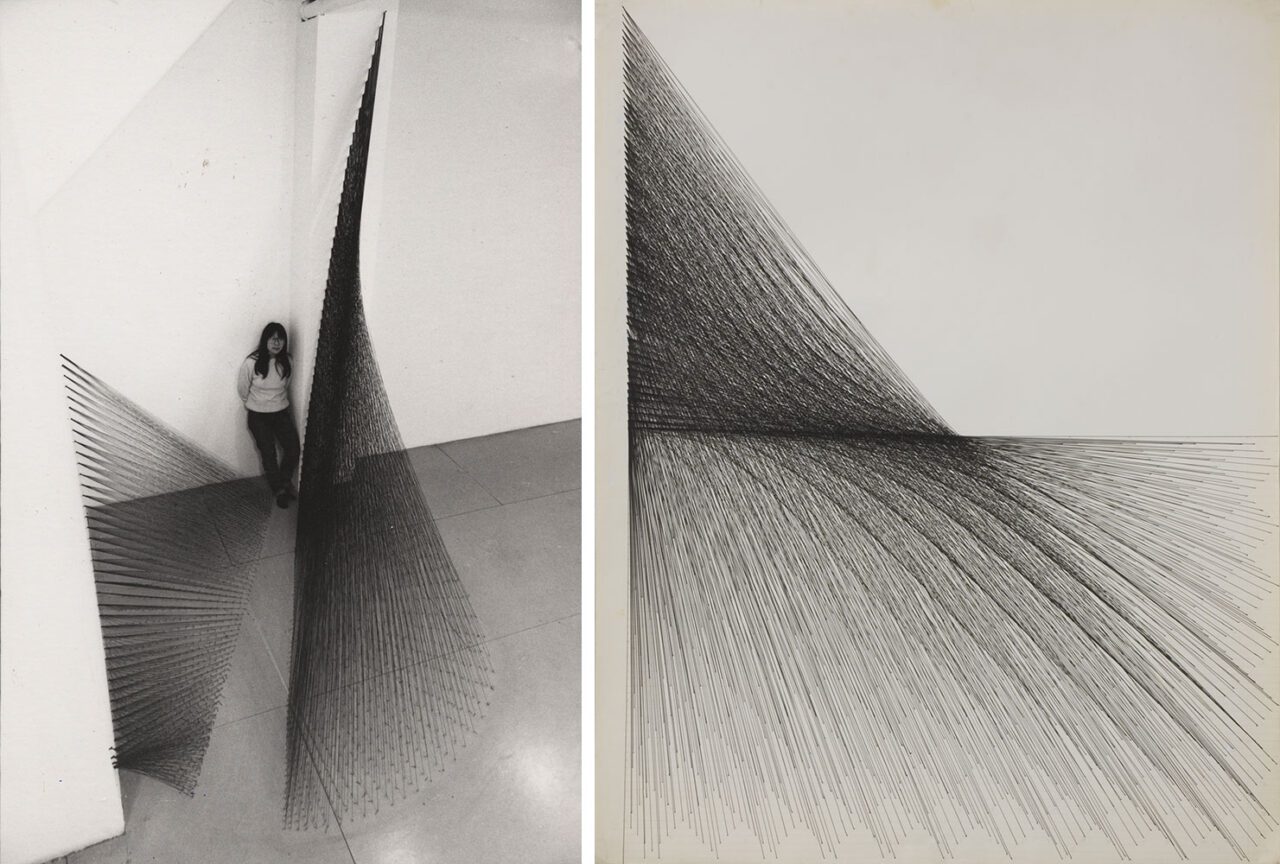

With her ephemeral, sometimes radical works, Kazuko Miyamoto expands the boundaries of Minimal Art and defies simple categorizations. The Belvedere is honoring the Japanese American artist’s oeuvre with the largest international retrospective to date. The exhibition comprises around 120 exhibits from the late 1960s to the 2010s, including loans from renowned institutions such as the Met, the Guggenheim, Lentos, SFMOMA, and MADRE. On display are the artist’s early paintings, photographs, drawings, installations, and iconic string constructions— including the approximately three-meter-high, two-part work “Black Poppy”, or the equally large-format work “Trail Dinosaur”, which was first shown in 1979 together with a performance by Japanese dancer Yoshiko Chuma and is now being presented for the first time since then. A special program at Belvedere 21 in February will also feature performers who will bring the works to life. When Kazuko Miyamoto moved from Tokyo to the United States in 1964, she began studying painting at the Art Students League of New York. Initially expressionist in style, her paintings were increasingly inspired by the simple, reduced forms of Minimal Art: patterns, grids and precise structures became the defining elements of the artist’s formal vocabulary.While the three-part work “Progression of Rectangles” (1969) still follows a clear pictorial structure—its lines and the rectangles in between can be imagined as infinite—the geometric severity of her style was already softening by the time she created “GO” (1971). The title of this large-format canvas is derived from a board game popular in Japan and China, in which two players alternately place black and white pieces on the free intersections of a grid. In Miyamoto’s work, the black pieces cover almost the entire surface—an improbable arrangement. Executed in charcoal, the contours blur and vibrate, thus bearing similarities to the Japanese tie-dyeing technique shibori. Such imprecisions, introduced by Miyamoto in her early paintings, characterize her own, liberated approach to Minimal Art. Kazuko Miyamoto’s encounter with the US artist Sol LeWitt, whom she met in New York in 1968, had a lasting influence on her artistic practice. A pioneer of Minimal Art and Conceptual Art, LeWitt developed the ideas for his own works but had them executed by other people. When Miyamoto began working for him that year as a production assistant, she was entrusted with the realization of his modular sculptures and “Wall Drawings”. At the same time, Miyamoto was also working in her own studio, where she was carrying out intensive explorations of the line as a motif—initially still on paper. Characterized by repetition and overlapping, concentration and emptiness, her drawings break away from the strict structures of Minimal Art through their deliberate irregularities. The unevenly spaced, partially overlapping strokes not only raise questions about space and form finding; the artist was also establishing an increasingly individual, minimalist language. Her drawings on paper are autonomous works that sometimes also served as preparatory sketches for the string constructions that followed. For the “string constructions” she created from the early 1970s onwards, Kazuko Miyamoto began experimenting with cotton threads, which she stretched along the wall in her studio at regular intervals and fixed in place with nails. The simple geometric patterns, which initially followed the joints between the bricks, became increasingly complex and eventually acquired a three-dimensional quality. In these works, Miyamoto transfers lines into space and through their condensation develops a wide variety of geometric forms that are elongated: “Female I” (1977), conical like “Untitled” (1978), or rounded like “Archway to Cellar” (1978). Other works, such as the two-part construction “Black Poppy” (1979), are formed from curved shapes that open up and demarcate an intermediate space. The result of a lengthy manual process, the artist’s string constructions are ephemeral installations that temporarily occupy the exhibition space. Their rhythmic repetition of lines in space produces an optical effect that lends these structures a unique presence and makes them appear to vibrate.

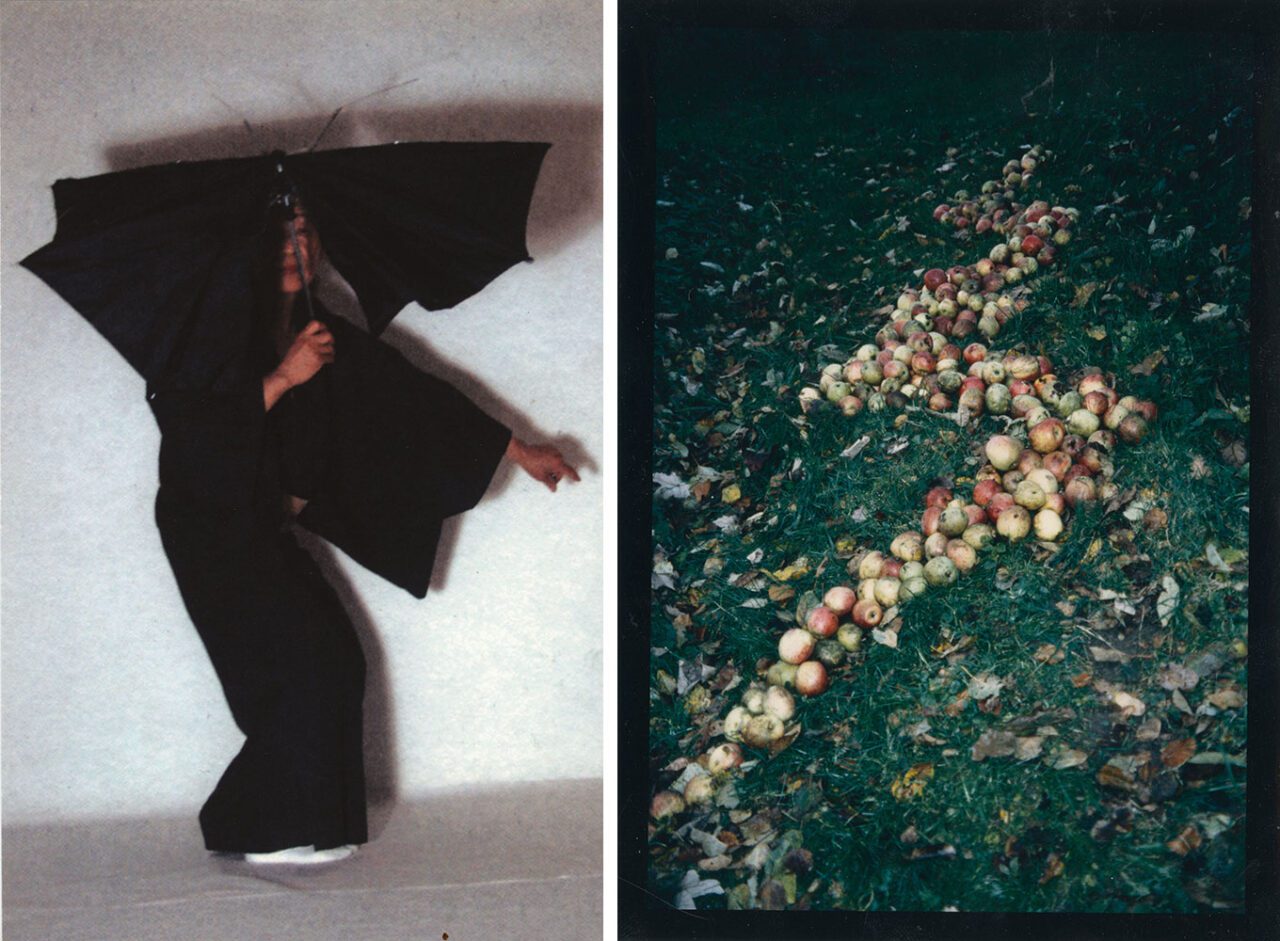

In 1980, Kazuko Miyamoto developed her first sculptural intervention in public space for the group exhibition “Art Across the Park”: “Shelter”, a free-standing construction made of branches and colorful ribbons, evoked the makeshift shelters erected by the numerous unhoused people who lived in Central Park at the time. In the same year, Miyamoto presented expansive objects made of twisted paper and branches in her solo exhibition “Nesting” at A.I.R. Gallery in New York. Reminiscent of birds’ nests, spirals, and ladders, the works allow for an intensive exploration of the bridge as a motif. Since then, the artist has realized most of her installations outdoors, connecting treetops or roofs together. While the raw material and archaic forms of this entirely new body of work may seem like a radical departure from the “string constructions”, these structures are also made from simple materials, are ephemeral in nature, and respond sensitively to their immediate surroundings. By presenting more of her work outdoors, Miyamoto opens her art to a broader audience and a direct interaction with the general public. Kazuko Miyamoto continuously combines her Japanese origins with Western influences, particularly those from her New York environment. In her practice, questions about the role of rituals and gestures crystallize in the motif of the kimono in particular, which is both a central element of her performances and an object in its own right. As traditional items of clothing that are passed down through generations, these garments are charged with cultural meaning. For Miyamoto, the kimono becomes a carrier of the personal memories that are inscribed in the object and therefore become an integral part of her art: For example, a photograph of her naked father, taken in secret, is printed onto delicate silk fabric (Standing Man, 1984), or a charcoal drawing of the Bowery Mission—a non-profit organization supporting the unhoused—is executed on a cotton kimono (Bowery Mission Kimono, 1990). The artist experimented with textiles, newspaper, and natural materials, making oversized kimonos or ones for her pets. Like other works in which she incorporates traditional Japanese elements, her kimonos also refer to bodily performance, cultures of memory, and the tense transfer of cultural codes. In her performances and staged photographs from the 1980s onwards, Kazuko Miyamoto explores issues relating to identity and femininity, self-determination and social status, ethnicity and memory. However, this shift from geometric, abstract works to an intensive engagement with personal themes is gradual and by no means exclusive; both aspects of her oeuvre continue to exist side by side. Seemingly mundane actions such as standing on a ladder (Manya and Kazuko in the loft on Chrystie Street, 1988), wearing a kimono (Plant Kimono, 1991), or sitting in the snow (Woman in Snow, 1998) are documented and recoded by Miyamoto. In Umbrella Dance (2004), for example, she combines the methodical movements of traditional Japanese dances such as odori with uninhibited gestures to American jazz music. The props used by Miyamoto, which are closely linked to her personal history and have a unique performative quality, serve as tools for redefining her individual, social and cultural identity. On her daily dog walks around the Lower East Side, Kazuko Miyamoto would closely observe her immediate surroundings. In the late 1970s, this historic New York neighborhood was badly neglected. Sex workers, street hawkers, and windshield cleaners known as squeegee men would all conduct their business here. The Bowery Mission, located right behind Miyamoto’s apartment, is a shelter for people seeking refuge. Equipped with a camera, the artist not only documented the urban landscape and its architectural features on her set routes, as in “Archways to Cellar” (1977); she also developed a growing familiarity with the people who lived there and made them the subject of her work. The black-and-white photograph “Ms. Broome and Ms. Chrystie” (1983), for example, portrays two sex workers standing at an intersection with their backs to the camera. To protect their identities, the women are named after the two streets and their faces cannot be recognized. With the presence of marginalized social groups as a recurring motif in her art, Miyamoto renders the often overlooked reality of poverty, unemployment, and social inequality visible—even taking on the role of an unhoused person herself in the performance “Waiting for Carnival”( 1983).

Photo: Exhibition view Kazuko Miyamoto, Belvedere 21, Photo: Kunst-Dokumentation.com, Manuel Carreon Lopez / Belvedere, Vienna

Info: Curator: Eva Fabbris, Assistant Curator Andrea Kopranovic, Belvedere 21, Arsenalstraße 1, Vienna, Austria, Duration: 12/9/2024-2/3/2025, Days & Hours: Tue-Wed & Fri-sun 11:00-18:00, Thu 11:00-21:00, https://www.belvedere.at/en

Right: Exhibition view Kazuko Miyamoto, Belvedere 21, Photo: Kunst-Dokumentation.com, Manuel Carreon Lopez / Belvedere, Vienna

Right: Kazuko Miyamoto, Fatatabi, 1987, Lentos Kunstmuseum Linz, Photo: Reinhard Haider

Right: Kazuko Miyamoto, Apple Snake dedicated to Tita in Ramsau, 1998, Installation of collected and arranged apples in the shape of a snake, Courtesy Kazuko Miyamoto

Right: Kazuko Miyamoto, Untitled, 1973, Courtesy Kazuko Miyamoto and EXILE