PREVIEW: Cerith Wyn Evans-Borrowed Light Through METZ

Beginning his career in the 1970’s as an experimental filmmaker, Cerith Wyn Evans has maintained his correspondence with conceptual art in his sculptures and installations. His works retain the cinematic qualities of his earlier career; however, the viewers are no longer merely passive observers- their bodily presence and changing perspectives play a central role. For over forty years, the artist has developed a unique practice through which he explores the limits of perception, and, in the process, calls into question the conventions of exhibition-making.

Beginning his career in the 1970’s as an experimental filmmaker, Cerith Wyn Evans has maintained his correspondence with conceptual art in his sculptures and installations. His works retain the cinematic qualities of his earlier career; however, the viewers are no longer merely passive observers- their bodily presence and changing perspectives play a central role. For over forty years, the artist has developed a unique practice through which he explores the limits of perception, and, in the process, calls into question the conventions of exhibition-making.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Centre Pompidou-Metz Archive

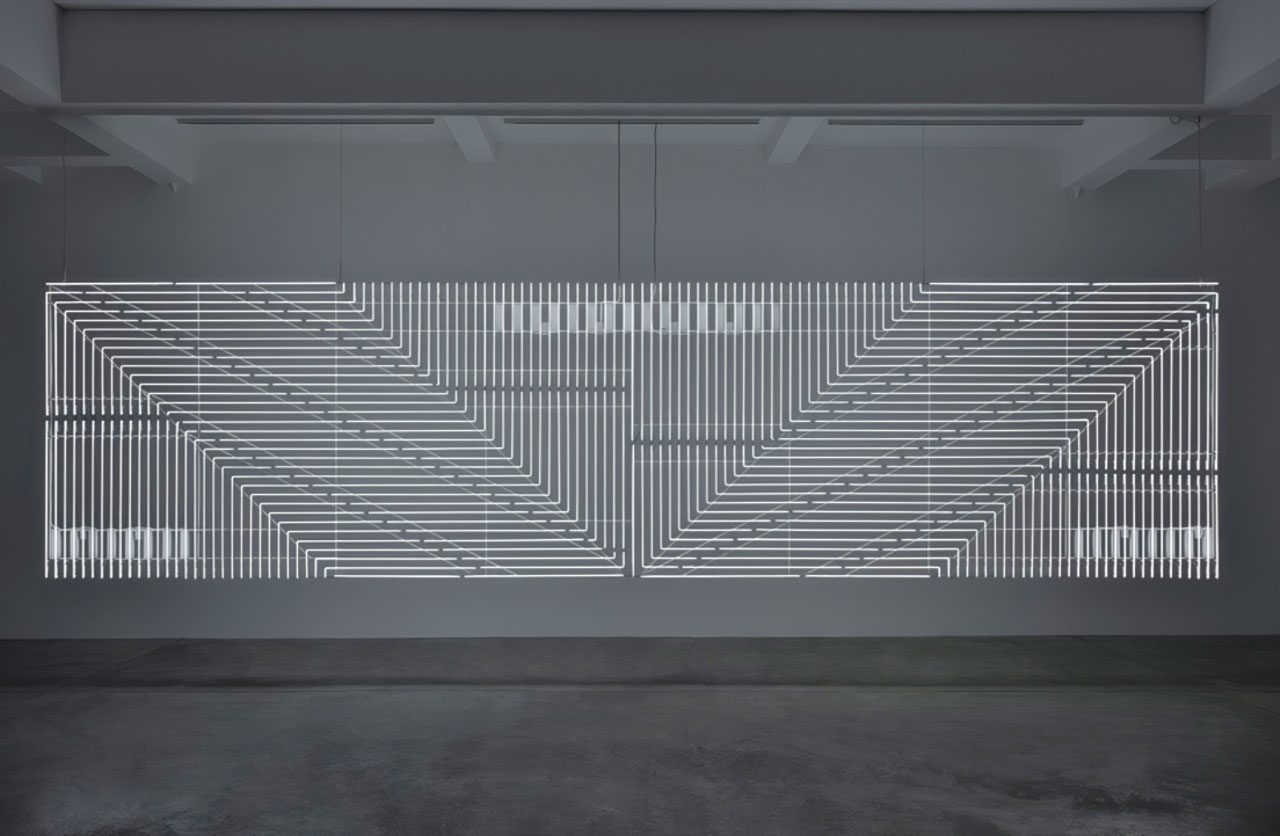

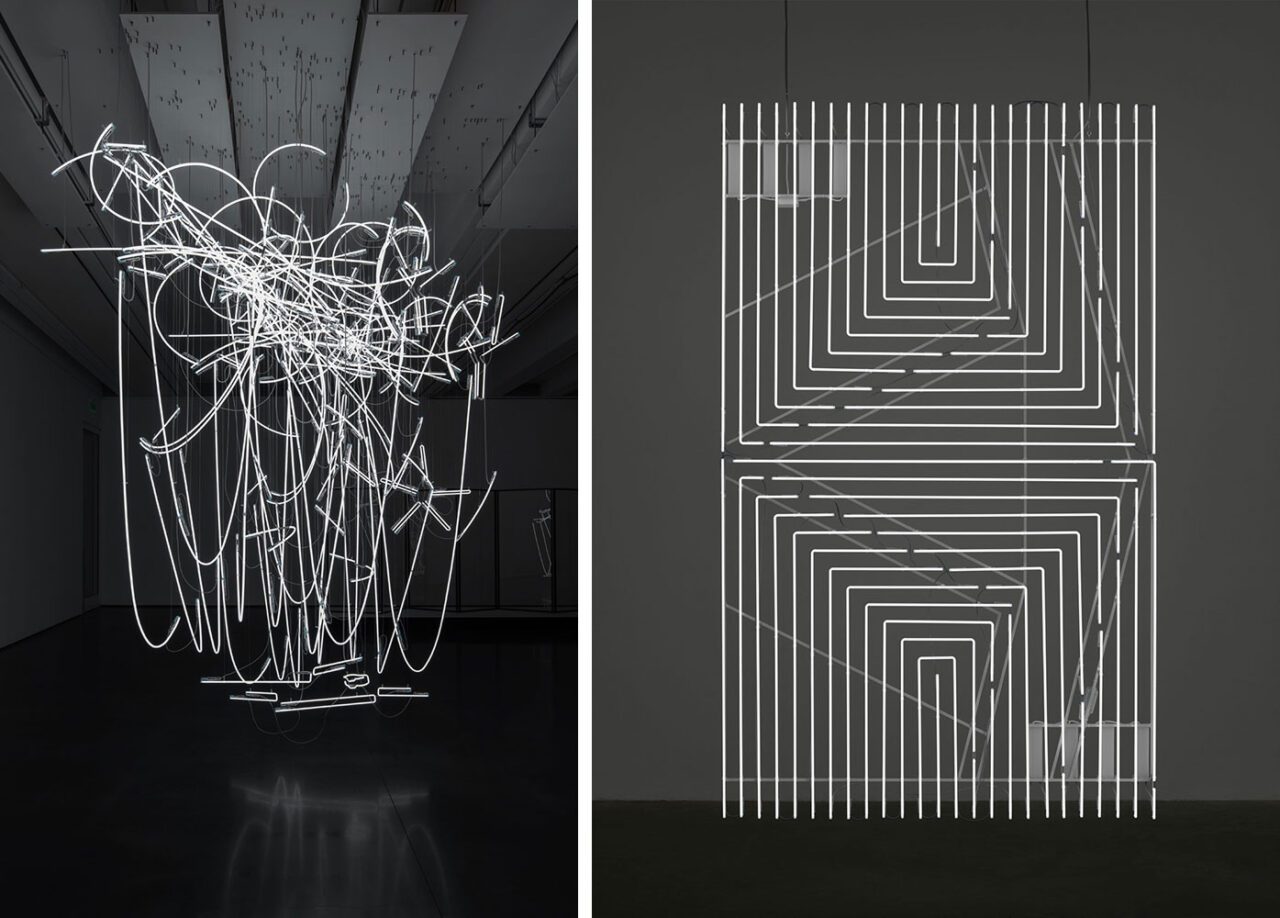

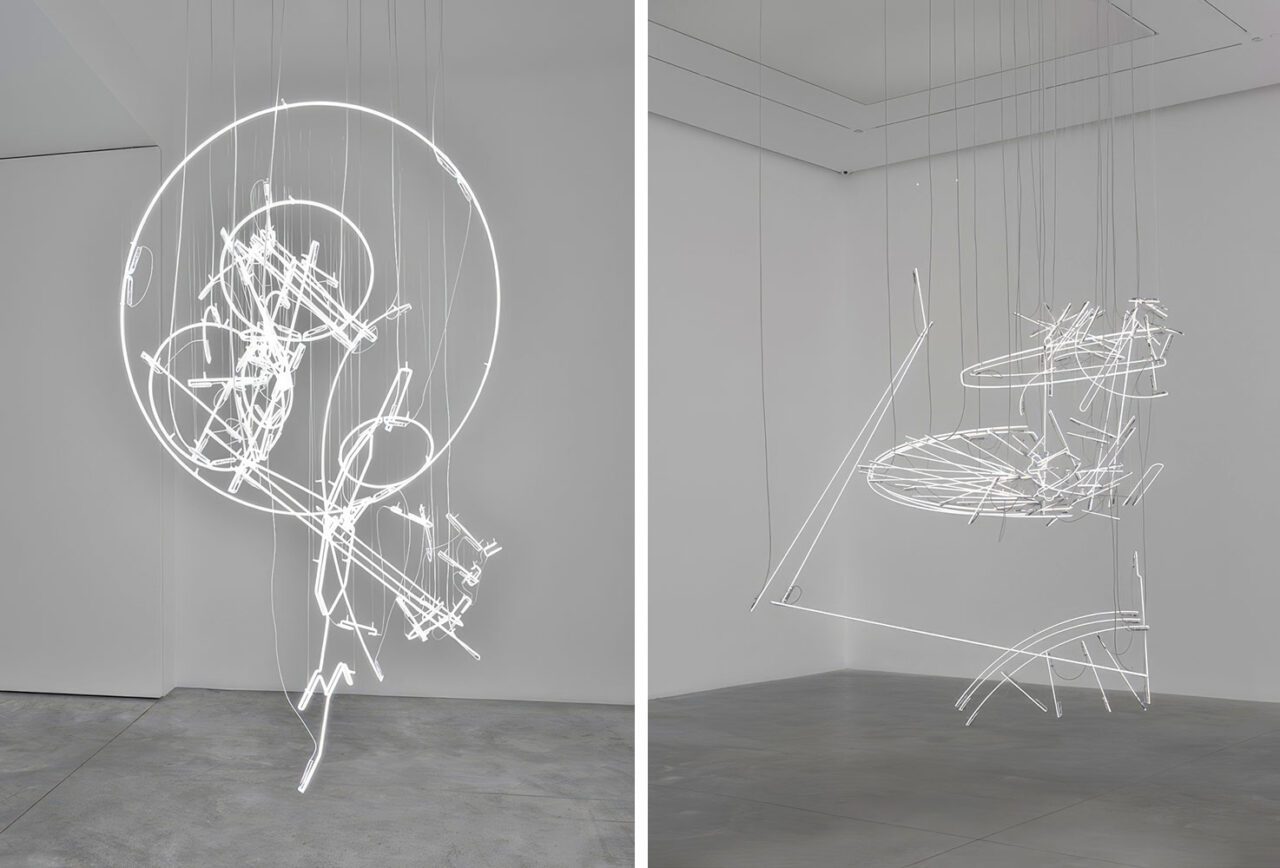

For “Borrowed Light Through METZ”, Cerith Wyn Evans presents his first solo exhibition in a French institution since his 2006 show at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris. Transforming the Forum and Gallery 3, he brings together light and sound works to occasion mises-en-scene of radiant visual and aural effects. Like characters in a repertory theater, older works return and interact with recent works to generate new scenarios. Each work remains singular yet the artist places them in concert in such a way that the exhibition constantly mutates as if animated by an inner life. The artist presents works that, among other themes, blurs the boundaries between nature and culture. At the same time, the garden plays off Shigeru Ban and Jean de Gastines’s architecture that folds the outside inside and the inside out. For this installation, the artist fills the space with plants that bathe in natural sunlight coming through the floor-to-ceiling windows. This light changes throughout the day and with the seasons. Cerith Wyn Evans’ many neon sculptures are animated from within by an invisible force the artist calls, ‘the illuminating gas.’ Neon bulbs can only produce light thanks to noble gases extracted from the atmosphere. Sealed inside the glass tubes, these inert gases, once an electric current passes through them, emit photons of light and glow. Speaking about the alchemical properties of the medium of neon, Wyn Evans states, ‘There’s a very mysterious, intractable, strange force, at work, energies that are very palpable.’ Playing on the fine line between the material and the immaterial, Wyn Evans’ series of suspended luminous sculptures, “Neon Forms (after Noh)” (2015–2019), acts as one such incarnation of this “magical” and “slightly otherworldly” gas. They have a colour temperature of 6500 kelvin, a cool blue light that equates to Northern daylight and leaves a lingering after image. Wyn Evans based these ‘neon forms’ on Noh theatre, a traditional form of Japanese theatre from the 14 century characterised by rigidly codified movements. Their design is based on ‘kata’ diagrams, the visual notations of Noh gestures used by actors to learn the complex and stylised choreography of Noh performances. These diagrams indicate gestures as subtle as the stamping of a foot, the cocking of a head, the opening and closing of a fan, and the slight folding of kimono fabric. In a process of translation and transition, the chandeliers in “Mantra” (2016) convert sound into light. This work consists of two ornate, more than two-metre-long chandeliers designed by the Venetian glass workshop of Galliano Ferro. Made from hand-blown Murano glass, the chandeliers have multiple arms that drape down like vines and blossom with intricately rendered flowers, a style that recalls a bygone elegance. In one of Wyn Evans’ typical sleights of hand, the chandeliers look identical when one of them is bigger than the other. What appear as mirror images do not reflect each other. Blinking on and off, the pair of light fixtures equipped with electronic processing devices reinterpret a recorded piano piece composed and performed by Wyn Evans himself. Since the early 2000s, Wyn Evans has made a number of chandeliers that communicate through blinking lights. In a techno-animistic duet, the chandeliers appear to channel outside voices as they glitter in a silent symphony of light. Wyn Evans in “Pli S=E=L=O=N Pli” (2020) transformed seventeen transparent glass panels into speakers and suspended them from the ceiling. These panels create ‘chambers’ into which the visitors can enter and be enveloped in sound. Each panel diffuses a mixture of sounds and songs that include a piano score composed and played by the artist himself and sounds from outer space. For the latter, the artist used clips from r a d i o q u a l i a, an experimental music station that in the early 2000s used specialised equipment to capture and broadcast sounds transmitted by satellites orbiting the Earth. The title was derived from Pierre Boulez’s musical composition “Pli selon pli. Portrait de Mallarmé” (1957-1990). According to Boulez, the composition paints a portrait of the poet ‘fold by fold’. This phrase Boulez took from a Mallarmé poem which describes how a morning fog covering the city of Bruges slowly unfolds until the stone buildings of the city emerge. Wyn Evans creates images of such unstable, formless states. In addition, the title of the piece enfolds into itself the philosophy of Deleuze, who has been a constant inspiration for Wyn Evans. In his book “The Fold”, Deleuze brings up Boulez’s composition based on Mallarmé and writes that the fold was the poet’s most important notion. Consisting of a multiplicity of particles of heightened kinetic energy, the images in Pli S=E=L=O=N Pli hover at the threshold of immateriality. Evans’ source material for his “Neon after Stella” (2022) works is the group of black paintings Frank Stella began in 1958. On why he chose this series as his subject, Wyn Evans states, ‘to a certain extent, I think of the Stella originals as some kind of score that I’m playing by transcribing it into another visual and spatial register.’ For this series, Wyn Evans remade the black paintings in white neon. More precisely, he left void the predominant black bands of the paintings and he transmuted the intervening stripes of blank canvas into neon tubes. He, thereby, reversed the positive and negative fields of Stella’s geometric, symmetrical order while also breaching their wholeness. Like most of Wyn Evans’ works in the exhibit, these large luminous screens hang from the ceiling, and visitors can walk around them as well as see through them. Varying with the point of view, the screens overlap and combine to create moiré interference patterns. Wyn Evans instills his work with an ongoing performativity. Subject and object evolve in time as their relation to each other constantly changes in an aesthetic flux. As a number of Wyn Evans’ sculptures, “phase shifts (after David Tudor)” (2023), allude to Duchamp’s “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even”. The series consists of car and truck windscreens hung together as mobiles in groups of two or three. The artist broke the glass himself with a hammer. The cracks mark the meeting of an intensive force and an extensive matter, i.e. time and space. Like many of the works in the exhibit, these windscreens can be walked around and looked through. The cracked glass continuously reflects, refracts, fragments, and distorts the surrounding works and visitors in a dizzying change of point of view. These windscreens recall computer screens, particularly those of frequently cracked cell phones, which have become ubiquitous interfaces in a global network. The ‘phase shifts’ of the title refers to a process often used in electronic music by experimental composer David Tudor and others. Synthesising multiple waveforms, they generate feedback loops or sonic echoes.

Photo: Cerith Wyn Evans, phase-shifts (after David Tudor) II , 2023, Installation view Marian Goodman Gallery Paris, © Cerith Wyn Evans / Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman, Gallery / Photo credits: Rebecca Fanuele

Info: Curator: Zoe Stillpass, The Centre Pompidou-Metz, 1 parvis des Droits-de-l’Homme , Metz, France, Duration: 1/11/2024-21/4/2025, Days & Hours: Mon & Wed-Sun 10:00-18:00 (1/11-31/3) & Mon, Wed-Thu 10:00-18:00, Fri-Sun 10:00-19:00 (1-21/4), www.centrepompidou-metz.fr/

Right: Cerith Wyn Evans, Neon after Stella (Arundel Castle), 2022, Installation view Marian Goodman Gallery Paris © Cerith Wyn Evans Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery / Photo credits: Rebecca Fanuele

Right: Cerith Wyn Evans, …take Apprentice in the Sun, 2020 © Cerith Wyn Evans. Photo © White Cube (Theo Christelis)