ART CITIES: Paris-Expanded Horizons, American Art in the 70s

Assembling major works by 21 of the most influential artists working in USA the exhibition “Expanded Horizons: American Art in the 70s” retraces the radical artistic developments of this tumultuous decade. Bringing into conversation works across mediums that challenged the limits and expanded the horizons of artmaking, whether in scale, material, or the way they interact with the world around them, this exhibition encourages a re-examination of an important decade, and reflects on how the pioneering artists working during it interrogated and redefined contemporary conceptions of art.

Assembling major works by 21 of the most influential artists working in USA the exhibition “Expanded Horizons: American Art in the 70s” retraces the radical artistic developments of this tumultuous decade. Bringing into conversation works across mediums that challenged the limits and expanded the horizons of artmaking, whether in scale, material, or the way they interact with the world around them, this exhibition encourages a re-examination of an important decade, and reflects on how the pioneering artists working during it interrogated and redefined contemporary conceptions of art.

By Dimitris Lempesis

PHOTO: Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery Archive

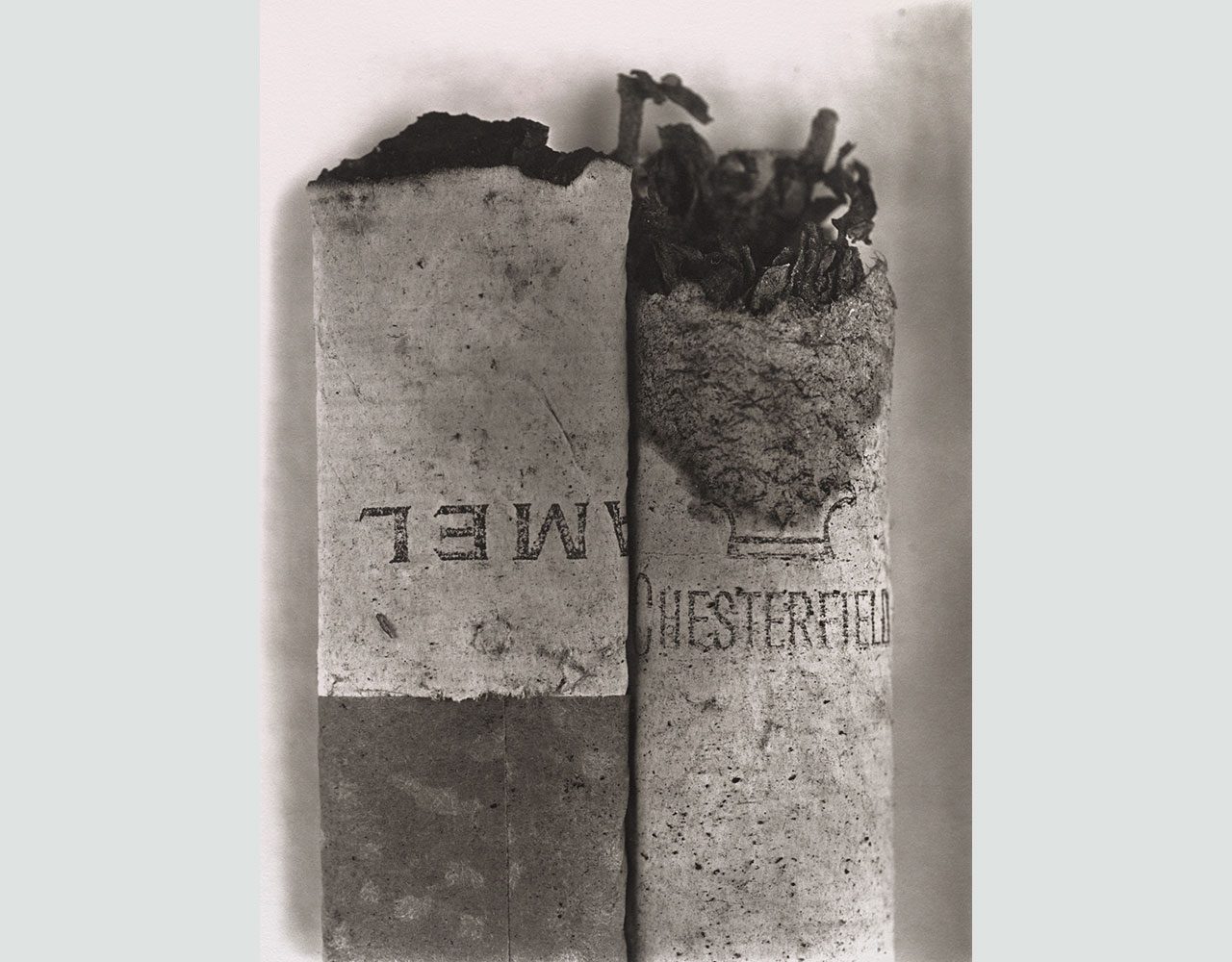

In the United States, the ‘counter-cultural’ 1960s came to a close amidst socio-political unrest – protests against the Vietnam War, the climax of the Civil Rights movement, as well as an ever-accelerating rhythm of technological breakthroughs. The dawn of the 70s was marked by upheaval and transformation. In 1970, Robert Rauschenberg moved to Captiva, Florida and Mary Lovelace O’Neal to California, and the following year, James Rosenquist relocated to Florida and Donald Judd set up his studio in Marfa, Texas. This exodus provided these artists with larger studio spaces that allowed them to scale up their practices in the image of their new open-skied surroundings. Many of the works on view harness monumental scale and three-dimensional space to expand the scope of the art object, in some cases even beyond the bounds of the work itself, to become environmental or immersive. Among them is Rauschenberg’s “Bank Job” (1979), a work closely related to his “Spread” series. Made up of 15 panels, the work is one of the largest the artist ever produced and is shown here for the first time in Europe. For Judd, who had abandoned the canvas entirely to work directly in ‘real space’, the transition to working in three dimensions liberated him from the pictorial conventions of the two-dimensional canvas. Frank Stella meanwhile, had been pushing the boundaries of the picture plane since the 1960s through shaped canvases which adopted progressively more daring and irregular polygonal forms. In 1970, he commenced his decisive series of “Polish Village” works when his friend, the architect Richard Meier, gave him a book about wooden synagogues in Poland, whose striking angular forms Stella abstracted to make monumental wall reliefs. Building on the silhouettes of the shaped canvases of the previous decade, this series of “Polish Villages” was the first in the artist added a third dimension to create works that transcend the limitations of the canvas. James Rosenquist’s monumental 1970 installation “Horizon Home Sweet Home” takes the form of a ‘room’, made up of 27 distinct panels, which fills intermittently with knee-high fog. This fog is an ephemeral yet integral part of the installation and its presentation, enveloping the work’s lower half like a cloud, disorienting the viewer and challenging or unsettling their assumptions about where a horizon line might fall on the panels. The rarely exhibited installation, which was first presented in the year of its creation at Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, ‘was an extension of my concept of dissolving the painting as an object, immersing the viewer in the painting, and making it an environment’, explained the artist. A Sol LeWitt “Wall Drawing”, meanwhile, intervenes in the space on an even more fundamental level, being executed on the gallery wall itself following the conceptual artist’s instructions. Judy Chicago created pioneering performances outdoors that rejected the traditional modes of exhibition and commodification of art. Her 1971–1972 series of pyrotechnic performances, which took place in the California desert and are immortalised in the video work “Women and Smoke, California”, , also speaks to contemporary feminist concerns – Chicago enveloped the landscape in a haze of colored smoke to “soften that macho Land Art scene” – as well as to the emerging ecological movement: rather than altering or damaging the landscape, as did the interventions of the major male figures of the Land Art movement. In the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, Robert Morris moved away from the rigidity of his previous Minimalist works and towards a softer materiality, epitomised by his use of felt. In the 1978 work “Untitled (Brown Felt)”, loose pleats of the fabric fall away from the work’s central rectangular form in a symmetric composition that recalls the folds of origami and demonstrates the effects of the natural and inevitable force of gravity on a pliable material. Also on view are two “Drape” paintings by Sam Gilliam, acrylic-painted unstretched canvases that are draped from the wall, forming natural folds that give this traditional support an unprecedented sense of movement and depth. Works from this series enter into conversation with the surrounding space, revising the codes of the canvas and leading the way in the movement to free it from the stretcher. The exhibition features artists who engaged with the ‘real world’ by integrating found objects into their practice, an act that challenged and expanded contemporary definitions of what could be considered a work of art. Robert Rauschenberg’s “Cardboards” (1971–72), which he created in his then-newly opened studio in Florida, are made from found boxes that he either cut and reassembled to form a wall sculpture or stacked to form a freestanding installation. After Irving Penn’s mentor and fellow photographer Alexey Brodovitch died of cancer in 1971, Penn began his pivotal “Cigarettes” series, collecting discarded cigarette butts from the streets and taking them back to the studio. There, he carefully laid them out to produce photographic compositions that, with their refined geometry, echo Rauschenberg’s stacking and stapling cardboard boxes into pared-back and focused configurations against the wall. Penn’s attentive composition and magnification of the overlooked details of the cigarettes elevated them from litter to art object while uncannily personifying them in a comment on a society damaged by corporate irresponsibility and governmental negligence. In this way, the significance of Penn’s cigarettes goes beyond the status shift from generic debris to art: they are also imbued with a very particular narrative symbolism. Joan Snyder incorporated found materials – such as the chicken wire and fake fur seen in “Vanishing Theatre/The Cut” (1974). Their tactile materiality, alongside the words and letters arranged in a storyboard fashion in three parts, creates a dramatic narrative: that of the artist’s own experience of moving through the world. Snyder was a key figure in the women’s art movement that flourished in the 1970s, developing as part of the wider Second Wave period of feminist activity that occurred between the early 1960s and early 1980s. The movement sought to place women’s lives and realities at the heart of artistic expression, as well as calling for equality in the representation of women artists within the established art scene. In 1974, the year that Snyder painted the three-part work “Vanishing Theatre/The Cut”, she left behind her New York studio for a farm in Martins Creek, Pennsylvania. This year also marked a radically new painterly direction for the artist. Coming after a period during which she dissected the fundamentals of painting through intensive investigation of gesture and brushstroke, in this new series, Snyder gave the picture plane a new dimensionality through impasto layered with a lush materiality.

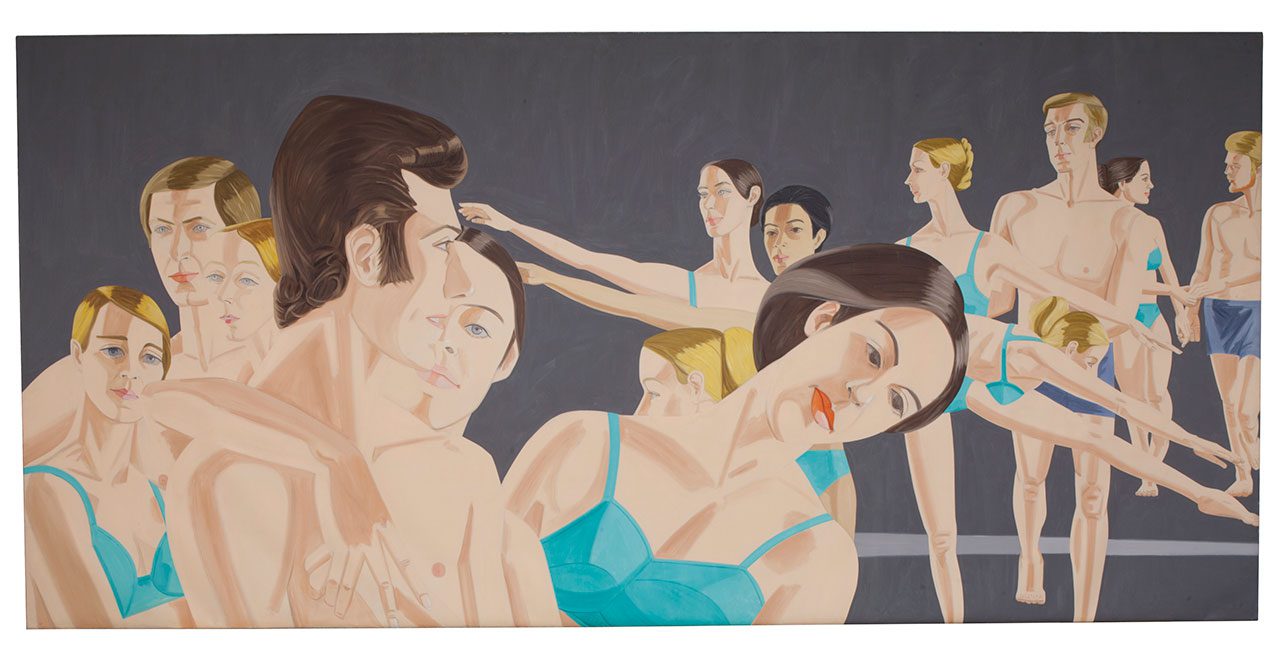

A John Chamberlain sculpture belonging to his most notable series of works assembled from found scrap automobile metal is shown alongside a copper work by Carl Andre. Andre, who made sculptures made from ordinary industrial materials, arranged on the floor in simple linear or grid-like compositions, passed away earlier this year. After Irving Penn’s mentor and fellow photographer Alexey Brodovitch died of cancer in 1971, Penn began his best-known series, “Cigarettes”, collecting discarded cigarette butts from the streets and taking them back to the studio. There, he carefully laid them out to produce photographic compositions, which elevated them from litter to art object, while un- cannily personifying them in a comment on a society damaged by corporate irresponsibility and governmental negligence. By working with scrap materials in their original condition, complete with stains, defaults or dirt, these artists draw attention to the character of the material itself. Other artists create a similar effect through paint, using expanses of uniform color to highlight their medium’s specific qualities, exploring notions of surface, space and light. Robert Ryman encourages an examination of the surface and boundaries of the picture plane by painting it entirely in white-on-white: ‘I am not a picture painter. I work with real light and space’. Judd’s deliberate use of color, which he viewed as something physical – a concrete formal entity – conveys the shape of his objects, lending definition to their planes and edges. By painting expanses of the work on view in blue, he brings together its color and its spatial dimension: ‘Color and space occur together’, as do light and space in the work of Dan Flavin. Rosenquist’s installation rejects figurative imagery, alternating canvases painted with planes of flat color with panels stretched with reflective silver Mylar film to create, in the artist’s words, ‘color as a state of mind’. Similarly, in paintings by Lovelace O’Neal and Snyder, panel-like blocks of color which seem to jostle within the picture plane as if competing for room allow for a more focused meditation on surface, space and texture, from Snyder’s pastose application to Lovelace O’Neal’s expressive brushwork, reconciling the intimate and the monumental, encouraging at once a focus on intricate materiality and a sense of its place as part of a wider vision. As Snyder explained: ‘I wanted more in painting, not less’. Both Lovelace O’Neal and Snyder worked against the conventions of male-dominated contemporary Minimalism and Color Field painting to explore the scope of abstraction to explore deeply personal and wider sociological narratives related to their lived experiences of womanhood, and, in Lovelace O’Neal’s case, Black womanhood, in 1970s America. In 1970, self-described ‘painter sculptor’ Rosemarie Castoro moved away from her previous colorful paintings in protest against the Vietnam War to dedicate herself to monochrome sculptural experimentation. The monumental works on view were made by applying gesso, modelling paste and marble dust to Masonite panels, giving the works a distinctive gritty yet refined texture. Castoro’s approach to artmaking was also informed by her background in dance, exhibiting a distinctly performative character and understanding of space and movement. With paintings depicting dancers, both Joan Brown and Alex Katz bring this same sense of depth and movement into the two-dimensional realm. As Katz recounts in his autobiography, his collaborations with dancers and choreographers as a set and costume designer ‘expanded the idea of what I could do. You’re not just a painter, you’re a person who has an idea about the art. Once you get that through your head, you have an expanded way of dealing even with your painting.’ The figure of the dancer rep- resents the multidisciplinary expansion of art in the 1970s, while testifying to the same understanding of motion, fluidity and the body in space evoked by Gilliam’s “Drape” paintings and Brown’s hanging work. Other artists use a more direct means to explore the human body and to examine how it exists in space and the world. Andy Warhol employed urine to produce a series of audacious “Piss” paintings, which he made by inviting members of his circle to provide samples or urinate directly onto the canvases. A monumental Piss work, measuring almost five metres in length, is included in the exhibition, as is a “Body Prin”t by David Hammons. Made by greasing his own body and pressing it against the paper, before embellishing the print with minute details of skin, hair or clothing through a process of one-to-one transfer and overlaying with accents in dry pigment, these works form intricate depictions of his own embodied experience as a Black man in America. Bringing into dialogue an exemplary body of works from this transformative decade, the exhibition sheds light on the 1970s as a watershed. Through their unconventional and radically egalitarian approach to materials and their common desire to deepen the way their practice occupies and interacts with the physical and conceptual landscape, the distinct practices of the 20 artists on view are united by a search to forge new lines of expression that spoke to the rapidly changing world around them, expanding art-historical conversation in a way that remains relevant to this day.

Works by: Carl Andre, Joan Brown, Rosemarie Castoro, John Chamberlain, Judy Chicago, Dan Flavin, Sam Gilliam, David Hammons, Donald Judd, Alex Katz, Sol LeWitt, Mary Lovelace O’Neal, Senga Nengudi, Irving Penn, Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist, Robert Ryman, Joan Snyder, Frank Stella, Andy Warhol

Photo: Joan Snyder, Vanishing Theatre/The Cut, 1974, oil, acrylic, paper mache, thread, fake fur, paper, chicken wire on canvas, 152,4 x 304,8 cm (60 x 120 in, © Joan Snyder, Courtesy the artist and Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Seoul

Info: Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery, 69 avenue du Général Leclerc, Pantin, Paris, France, Duration: 21/9/2024-25/1/2025, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-19:00, https://ropac.net/