PHOTO: Life Dances On-Robert Frank in Dialogue

Characterized by their pointed and complex critique of American culture and society, Robert Frank’s images often capture people in the throes of daily life. “There is one thing the photograph must contain, the humanity of the moment,” he once explained. “This kind of photography is realism. But realism is not enough—there has to be vision, and the two together can make a good photograph.”

Characterized by their pointed and complex critique of American culture and society, Robert Frank’s images often capture people in the throes of daily life. “There is one thing the photograph must contain, the humanity of the moment,” he once explained. “This kind of photography is realism. But realism is not enough—there has to be vision, and the two together can make a good photograph.”

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: MoMA Archive

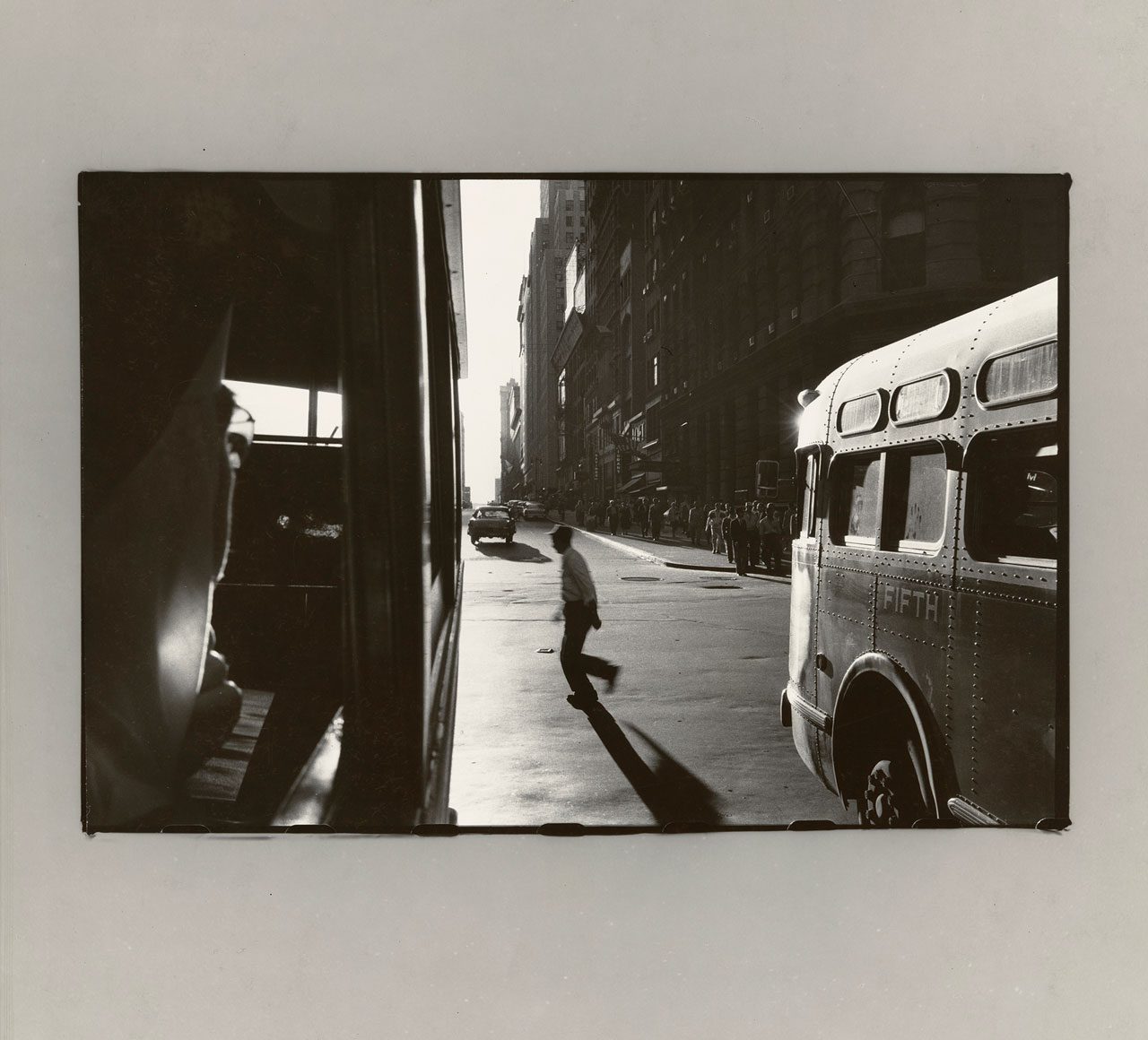

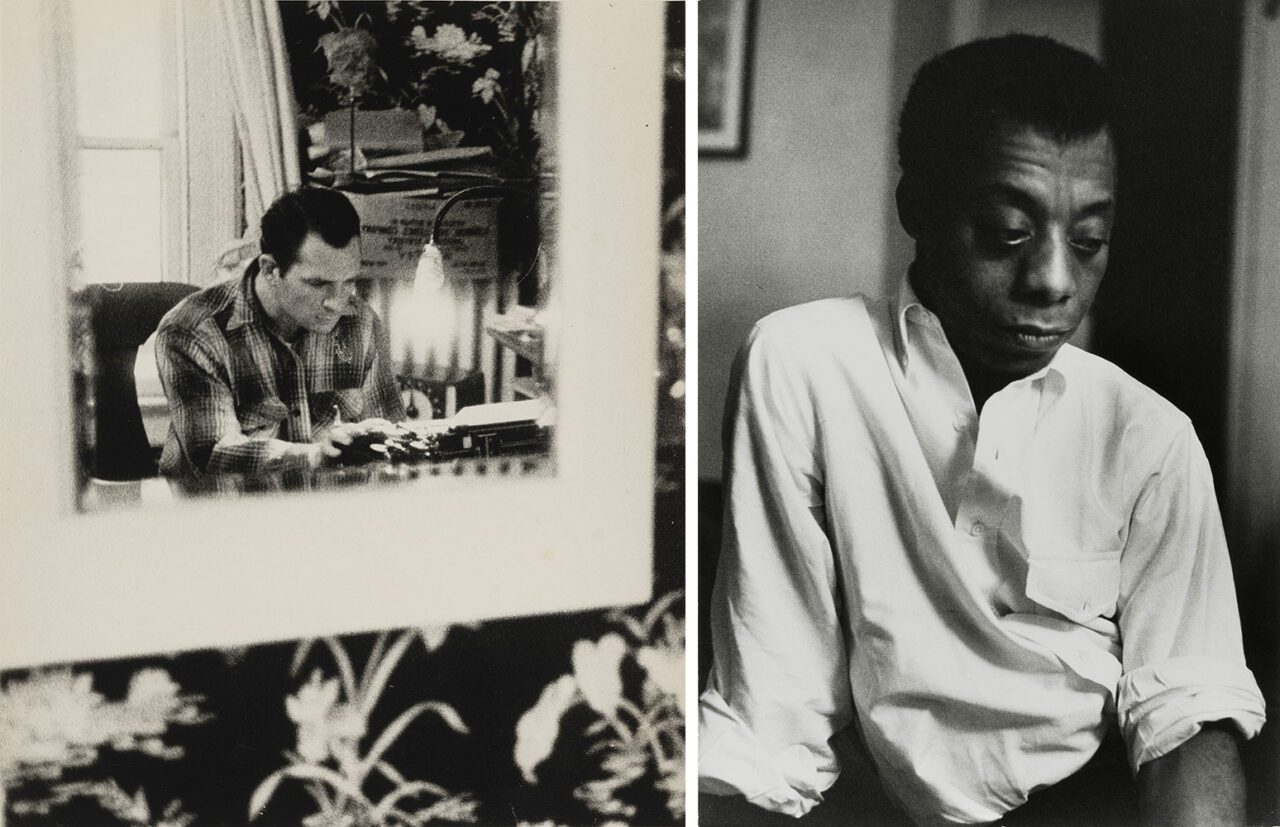

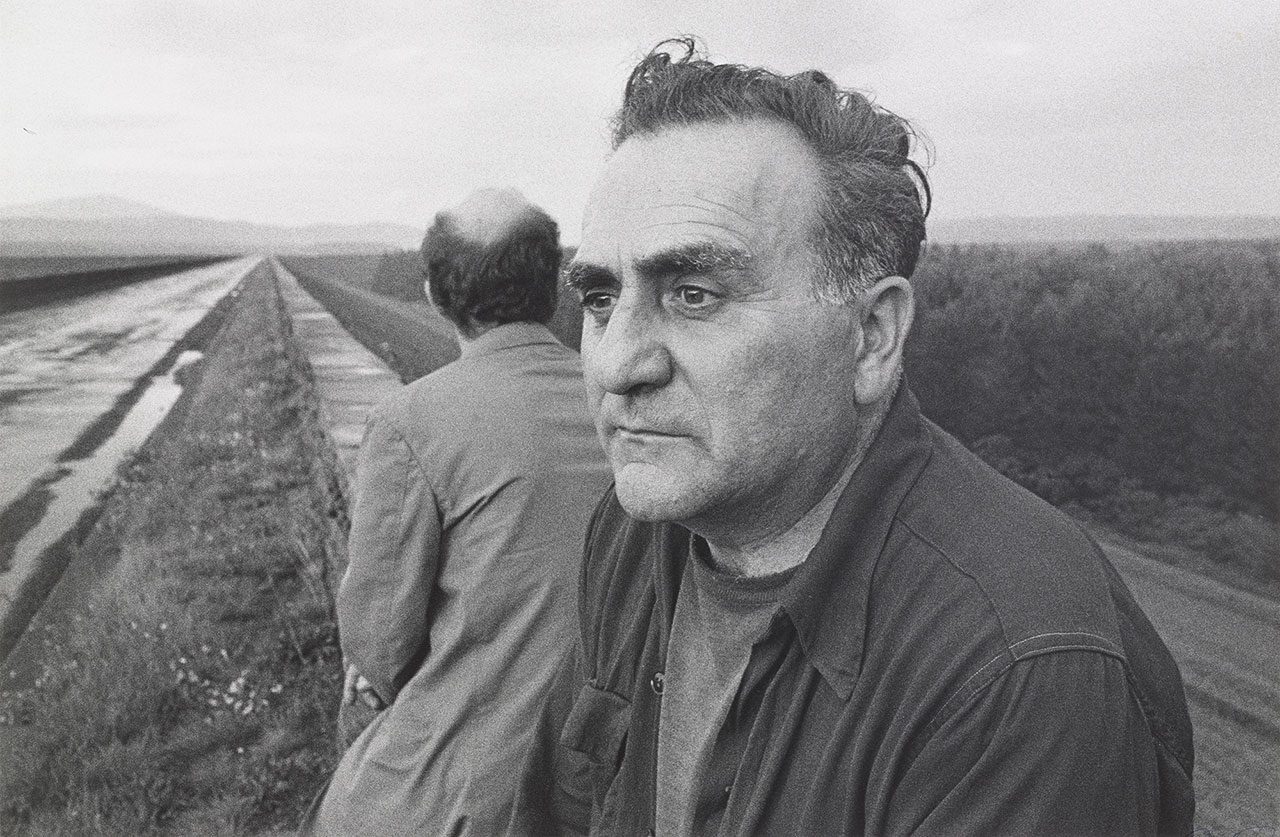

The exhibition “Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue”, provides new insights into the interdisciplinary and lesser-known aspects of photographer and filmmaker Robert Frank’s expansive career. Thee exhibition delves into the six decades that followed Frank’s landmark photobook “The Americans” (1958) until his death in 2019, highlighting his perpetual experimentation and collaborations across various mediums. Coinciding with the centennial of the artist’s birth, and taking its name from his 1980 film, “Life Dances On” explores Frank’s artistic and personal dialogues with other artists and with his communities. The exhibition features more than 250 objects, including photographs, films, books, and archival materials, drawn from MoMA’s extensive collection . Organized loosely chronologically, the exhibition focuses on the theme of dialogue in Frank’s work and reflects on the significance of individuals who shaped his outlook. Frank’s own words are present throughout the exhibition—in the texts he scrawled directly onto his photographic negatives and in the spoken narrative accompanying his films. Also revealed throughout the exhibition is Frank’s innovation across multiple mediums, from his first forays into filmmaking alongside other Beat Generation artists, with films such as “Pull My Daisy”(1959), to the artist’s books he called “visual diaries,” which he produced almost yearly over the last decade of his life. By focusing on dialogue and experimentation, the exhibition explores such enduring subjects as artistic inspiration, family, partnership, loss, and memory through the lens of Frank’s own personal traumas and life experiences. Among the works presented in the exhibition is a selection of photographs drawn from Frank’s footage for his 1980 film “Life Dances On”. These works reflect on the significance of individuals who shaped Frank’s own outlook—in this case, his daughter Andrea and his friend and film collaborator Danny Seymour. Like much of his work, the film finds its setting in Frank’s own communities in New York City and in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, where he and his wife, the artist June Leaf, moved in 1970. An abundance of material was loaned to the exhibition by the June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation, including works from the artist’s archives that are shown publicly for the first time, as well as personal artifacts, correspondence, and book maquettes. The summer of 1958 marked a shift in Frank’s work. He had already finalized the selection of pictures that would appear in his photobook The Americans. For a new series, Frank photographed passersby from the window of a New York bus as it traversed Fifth Avenue. The pictures—a sequence of frames that appear linked by his own movement—indicated a notable moment of change beyond a single, static image. In 1972 he reflected on their significance: “When I selected the pictures and put them together, I knew and I felt that I had come to the end of a chapter. And in it was the beginning of something new.” From his window across a courtyard, Frank could watch the painter Willem de Kooning as he paced in his studio and contemplated his canvas. “I think that the people that influenced me most were the abstractionist painters I met; and what influenced me strongly was the way these painters lived,” Frank said of his time embedded in New York City’s vibrant arts community. “They were people who really believed in what they did. So it reinforced my belief that you could really follow your intuition… You could photograph what you felt like.” During these years, Frank continued to earn a living by photographing artists and writers for magazine print commissions, while also embracing the creative challenges of filmmaking alongside photography. His proximity to a diverse group of painters, sculptors, writers, and poets in the late 1950s would lead to boundary-pushing explorations like his first finished film, “Pull My Daisy” (1959), co-directed with artist Alfred Leslie, and filmed in Leslie’s own loft. In 1968 Frank premiered his first feature-length film, Me and My Brother, at the Venice Film Festival. Built as a film within a film, the story prompts questions about participation in traditional society and culture, and about what experiences of life are understood as valid. “The truth is somewhere between the documentary and the fictional, and that is what I try to show,” Frank explained. “What is real one moment has become imaginary the next.” In the late 1960s and early 1970s, as Frank turned his camera toward friends and neighbors, he also captured events of the time—manifested in political protests, music, poetry, and other aspects of social change and counterculture. During this period, Frank contributed cinematography to films directed by others and also spearheaded his own projects, which featured both recognizable figures and everyday folks on the street.

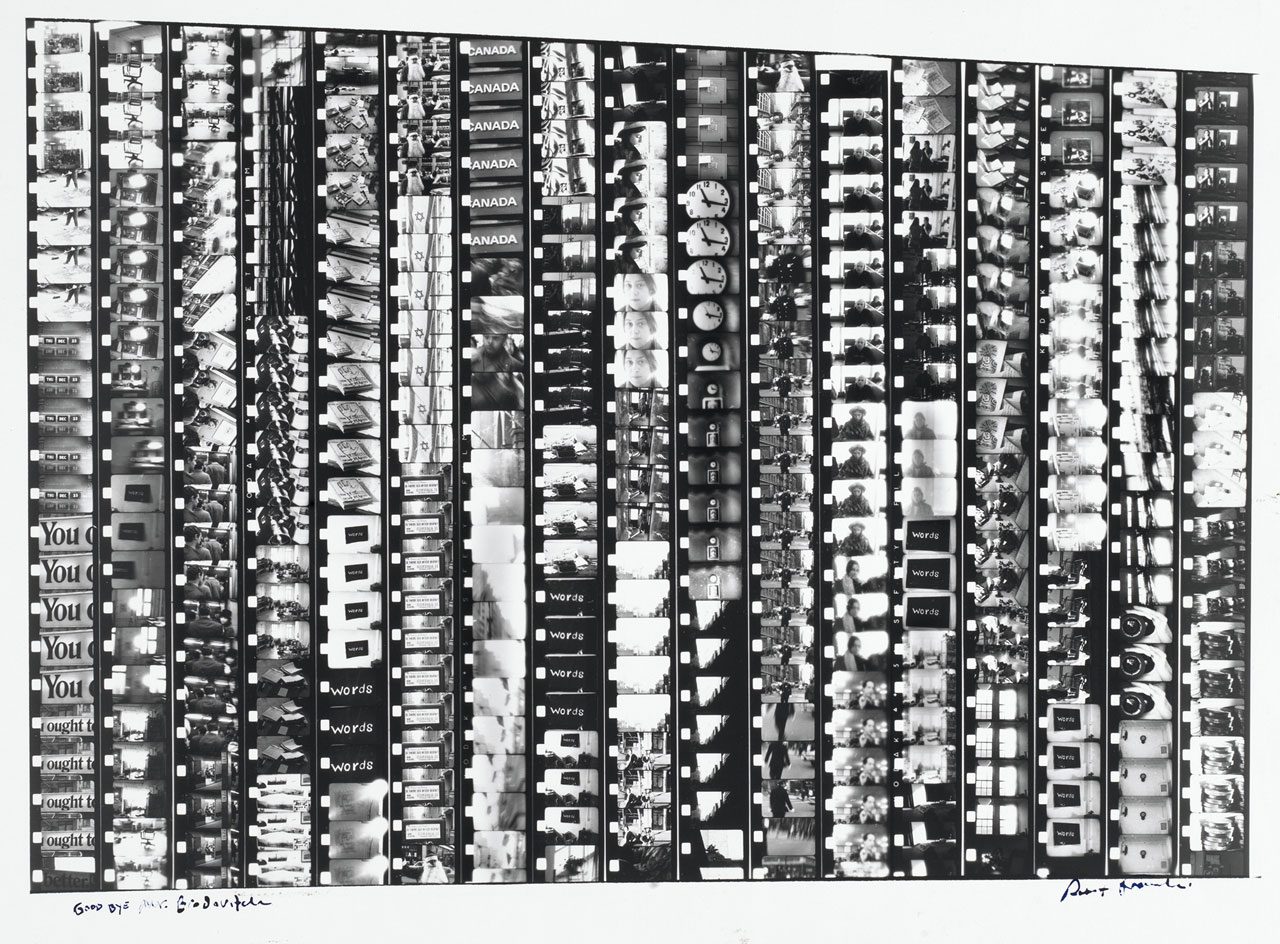

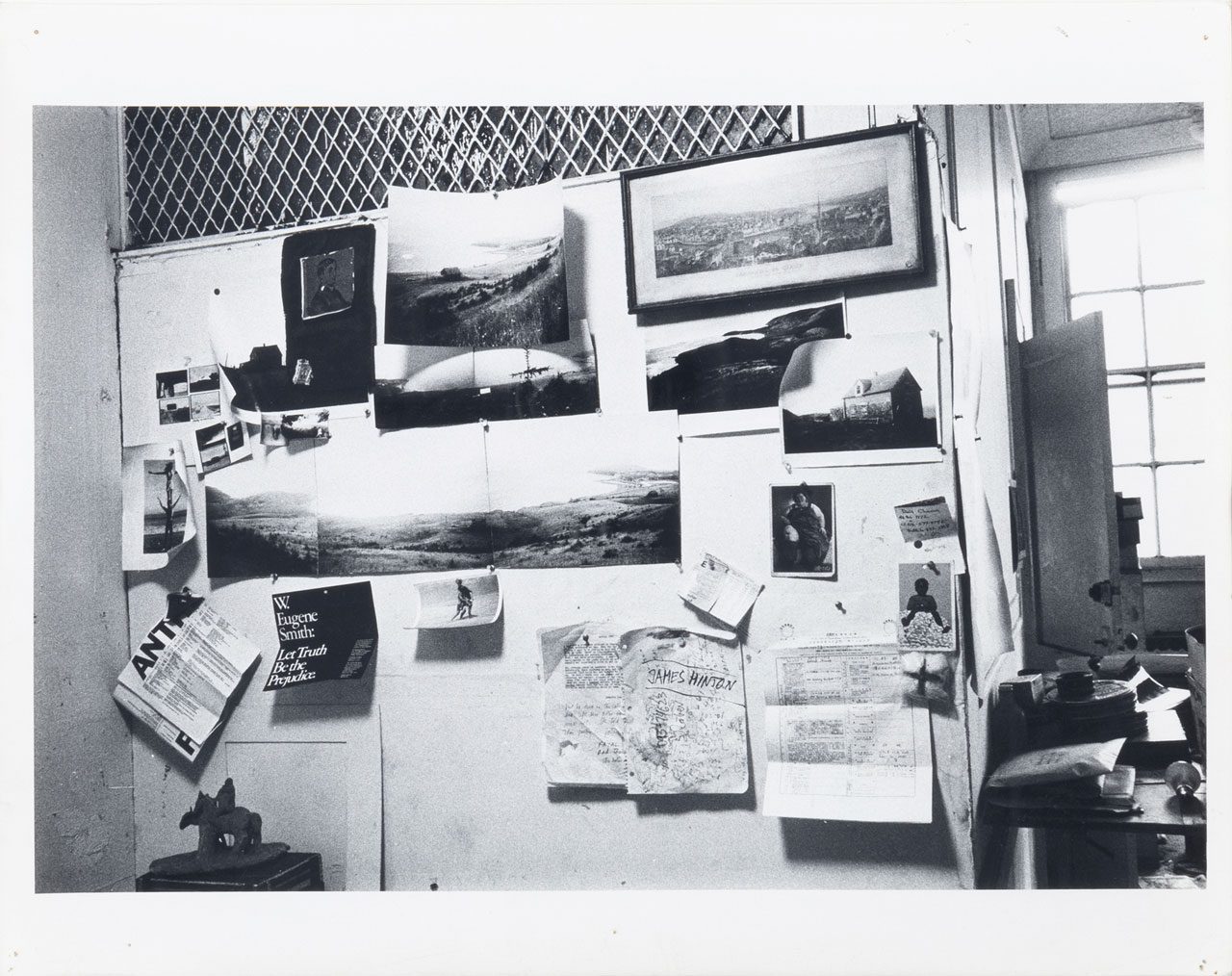

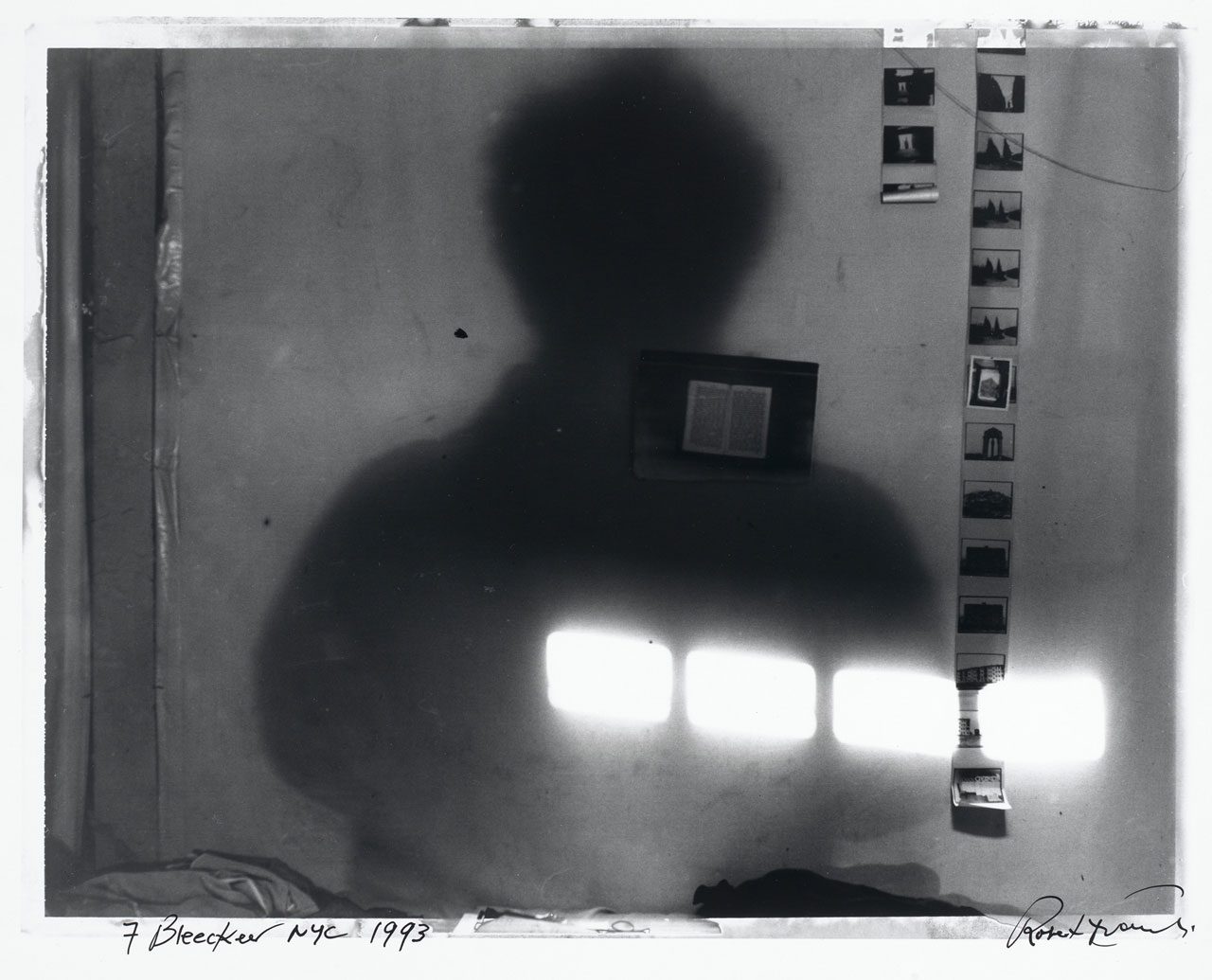

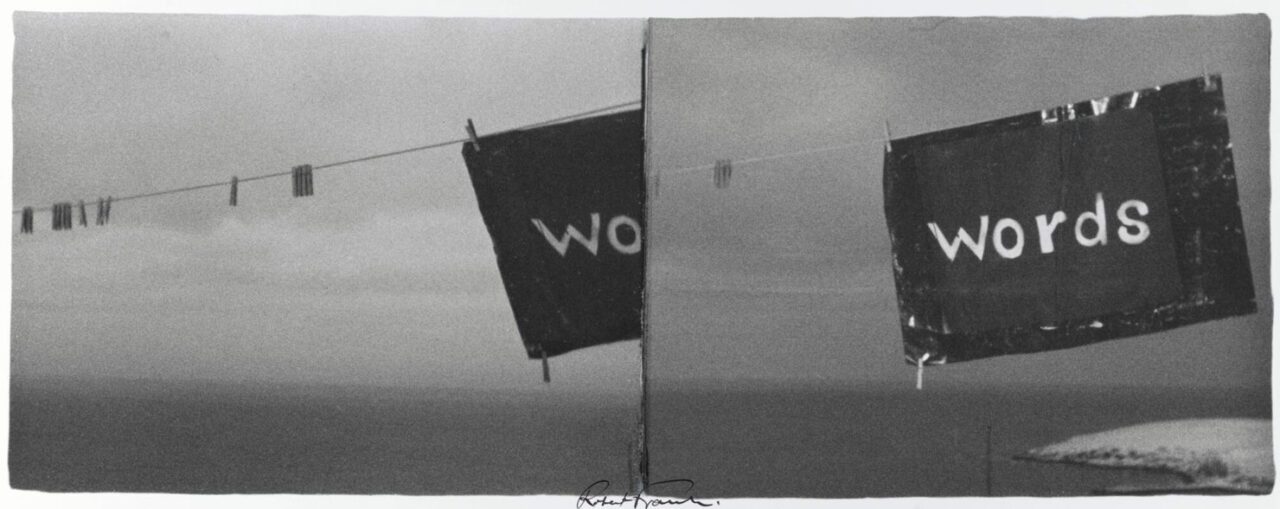

Frank’s photobook “The Lines of My Hand” offers a retrospective view of his career up until the date of its publication, in 1972. Pairing text and image, the book begins with early photographs made in Switzerland in the 1940s and ends with montages of film strips from Frank’s films of the 1950s and ’60s. Its title, perhaps a rumination on one’s past and one’s fate, is drawn from a sign pictured in a 1949 photograph of a Paris fortuneteller’s booth, on view here. “The Lines of My Hand” demonstrates Frank’s particular interest in the visual effects and meaning produced from combinations of images, either within a single photograph or formed by printing multiple negatives together to create a dense montage. In later editions, in keeping with his practice of revisiting and rearranging his images, Frank made changes to the photographs and graphic design and updated the book with his most recent works, using photocopies and notebooks to sequence the book’s new iterations. In 1970 Frank and Leaf relocated from New York City to the rural town of Mabou on Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, Canada. The photographer Walker Evans, Frank’s friend and mentor, came to visit them soon after at their old fisherman’s cabin overlooking the sea. Evans’s photographs capture the house’s hulking wood stove and the clothesline strung outside it, elements of the couple’s daily routine that also became material for artistic work. Living there, they “learned a completely different rhythm of life.” In Mabou, Frank’s work shifted its focus, becoming a means of processing his feelings, including profound grief. His change of environment, he acknowledged, had been significant. For Frank, the sea was a dynamic ground against which to measure his life. In the 1970s, Frank began regularly incorporating an instant print process, commonly known by the brand name Polaroid, into his work. He valued the immediacy of Polaroids, which enabled him to create an image instantly but then consider a work’s full composition over time. Throughout the rest of his career, Frank experimented with images by scratching words directly into the negatives and collaborating with printers to enlarge them into bigger prints and combinations. This process became especially significant for him after the sudden death of his daughter, Andrea, late in 1974. Frank began constructing monuments out of wood and materials around him in the landscape, which then figured into photographic memorials. In the early 1980s, Frank started using a Sony Portapak, a portable video camera that allowed him to instantly play back recordings. He could then erase, edit, and add new content on the tape. On video, Frank brought together fragments that at first seem unrelated, but through the choices he made while assembling them, offer a window into his personal preoccupations. “Home Improvements” (1985), Frank’s first work in video, was made between New York City and Mabou. From it, the artist made a new work in which he captured still images of the footage using a large-format Polaroid camera. The resulting photographs feature snippets of found text; portraits of family members; and—in the last image—Frank himself, captured in a reflection behind his camera. “I’m always looking outside, trying to look inside,” Frank narrates in the video. “Trying to say something that’s true. But maybe nothing is really true. Except what’s out there. And what’s out there is always different.” In his last decades, Frank’s work centered ever more upon his own life. Instead of traveling and looking outward, he found stories and compositions by panning his camera around his homes. His camera lingered on collected objects: figurines on the windowsill, postcards pinned to the wall, the typewriter on the table, and— always—photographs from years earlier. Frank also collected memories in his “visual diaries,” small, softcover books in which he, with his assistant, the photographer A-chan, arranged new and old pictures in sequences with personal resonance. Toward the end of his life, these photobooks became his main artistic output. Looking back at the souvenirs of his life—the settings in which it had taken place and the people who populated it—was incredibly generative: “Memory helps you,” he mused. “Like stones in a river help you to reach the shore.”

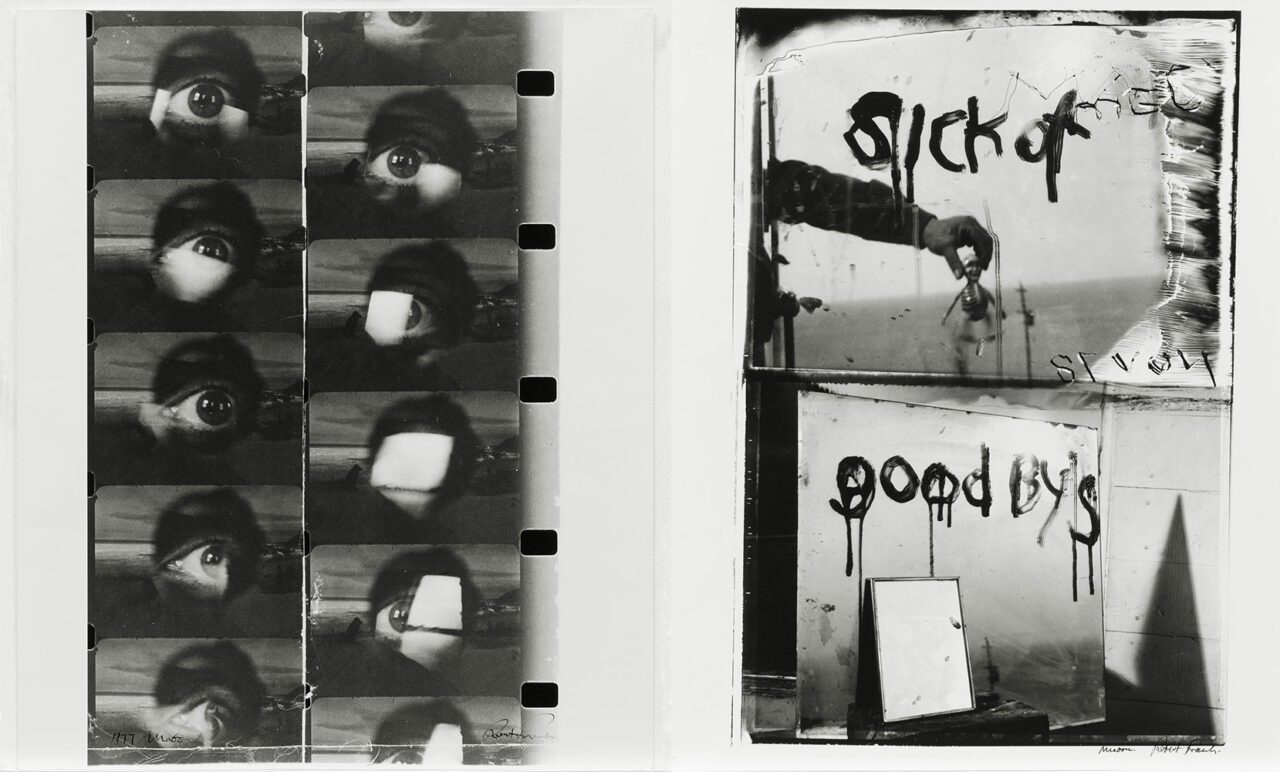

Photo: Robert Frank. Andrea. 1975. Five gelatin silver prints and ink on paper, 10 15/16 × 13 7/8″ (27.8 × 35.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, NY. Gift of the June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation in honor of Clément Chéroux and Lucy Gallun. © 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

Info: Curators: Lucy Gallun and Casey Li, MoMA (Museum of Modern Art), 11 West 53 Street, Manhattan, New York, NY, USA, Duration: 15/9/2024-11/1/2025, Days & Hours: Mon-Fri & Sun 10:00-17:30, Sat 10:30-19:00, www.moma.org/

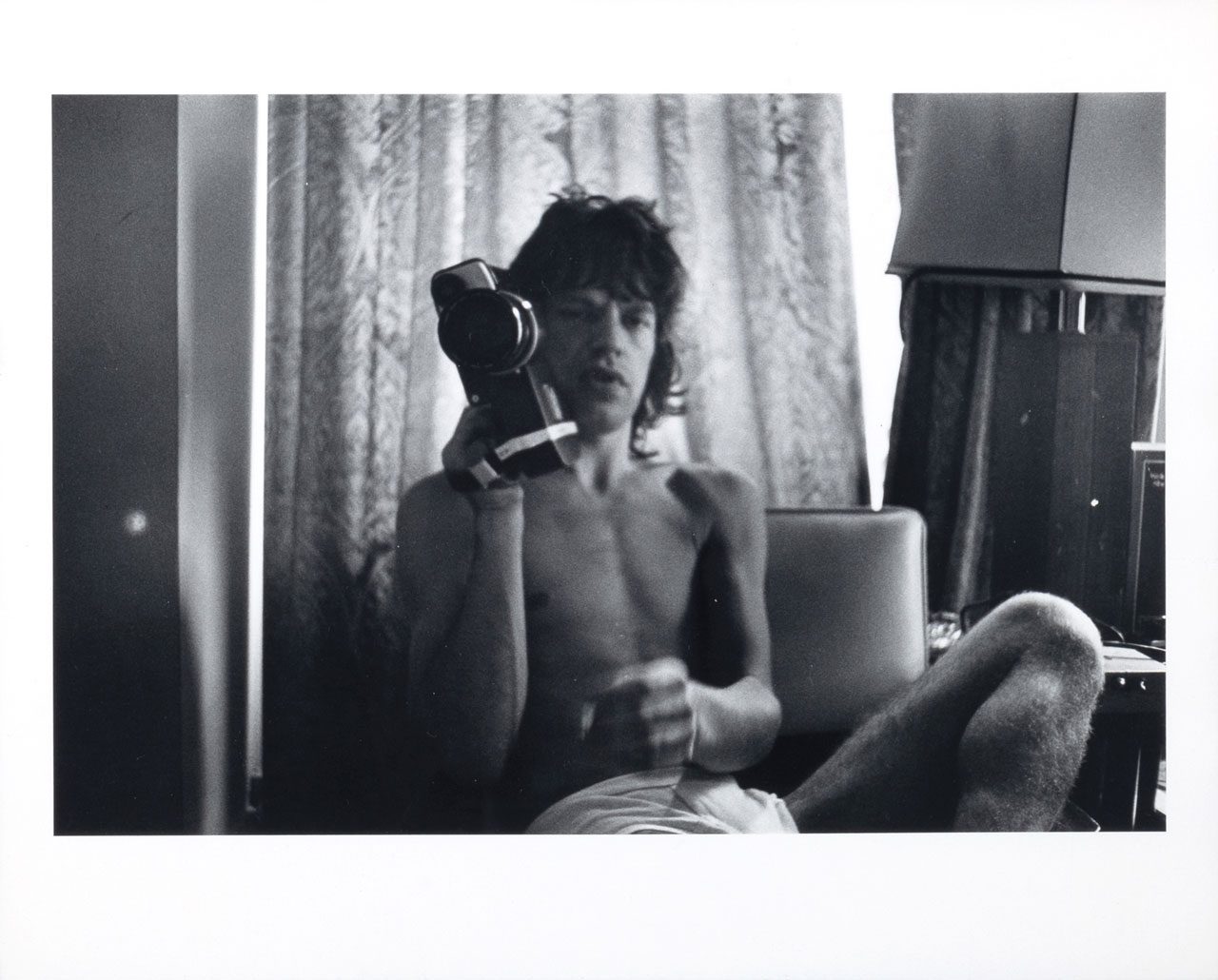

Right: Robert Frank. James Baldwin. c. 1963. Gelatin silver print, 13 15/16 × 9 13/16″ (35.4 × 24.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the artist. © 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

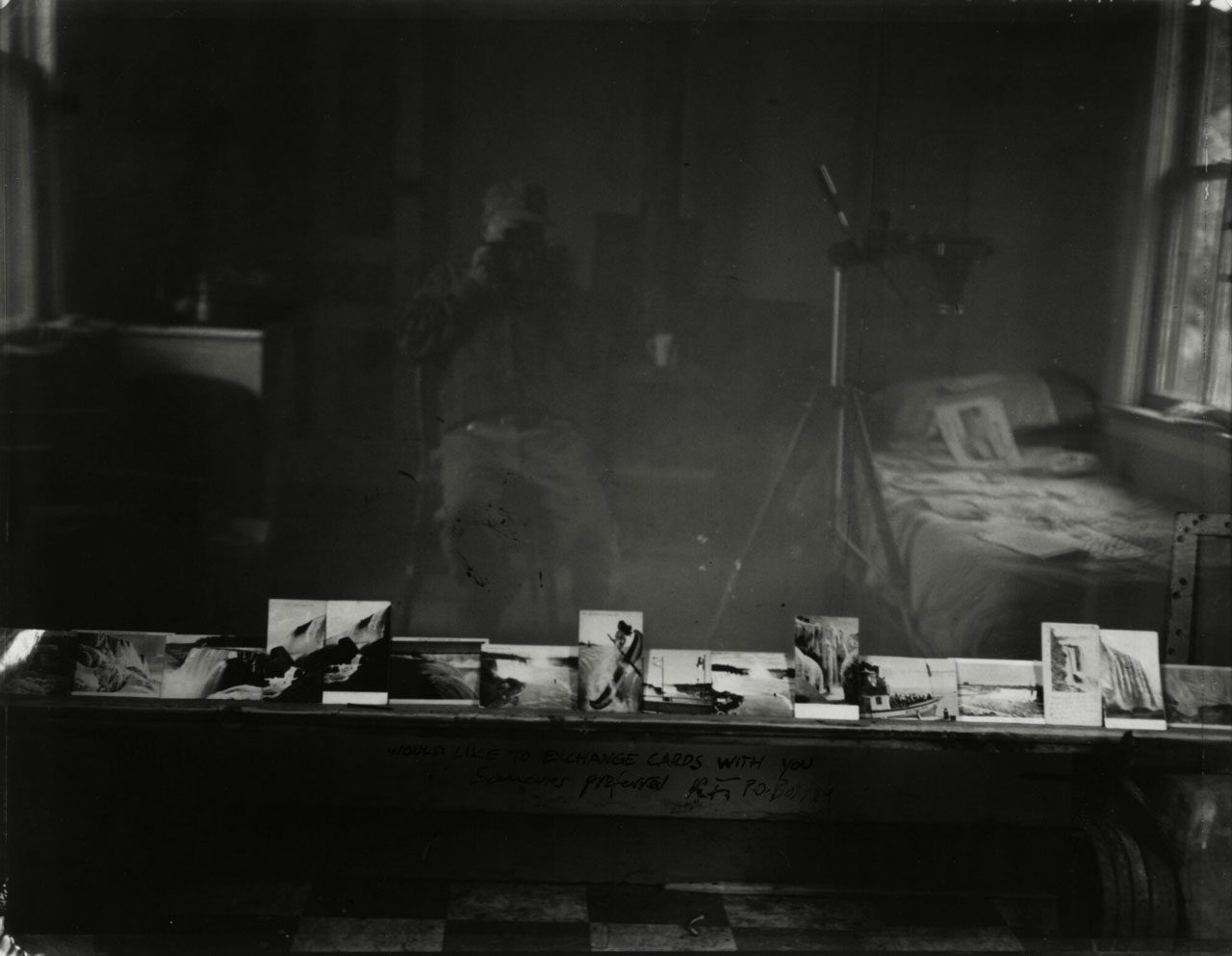

Right: Robert Frank. Sick of Goodby’s. 1978. Gelatin silver print, 21 15/16 × 12 11/16″ (55.8 × 32.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase. © 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

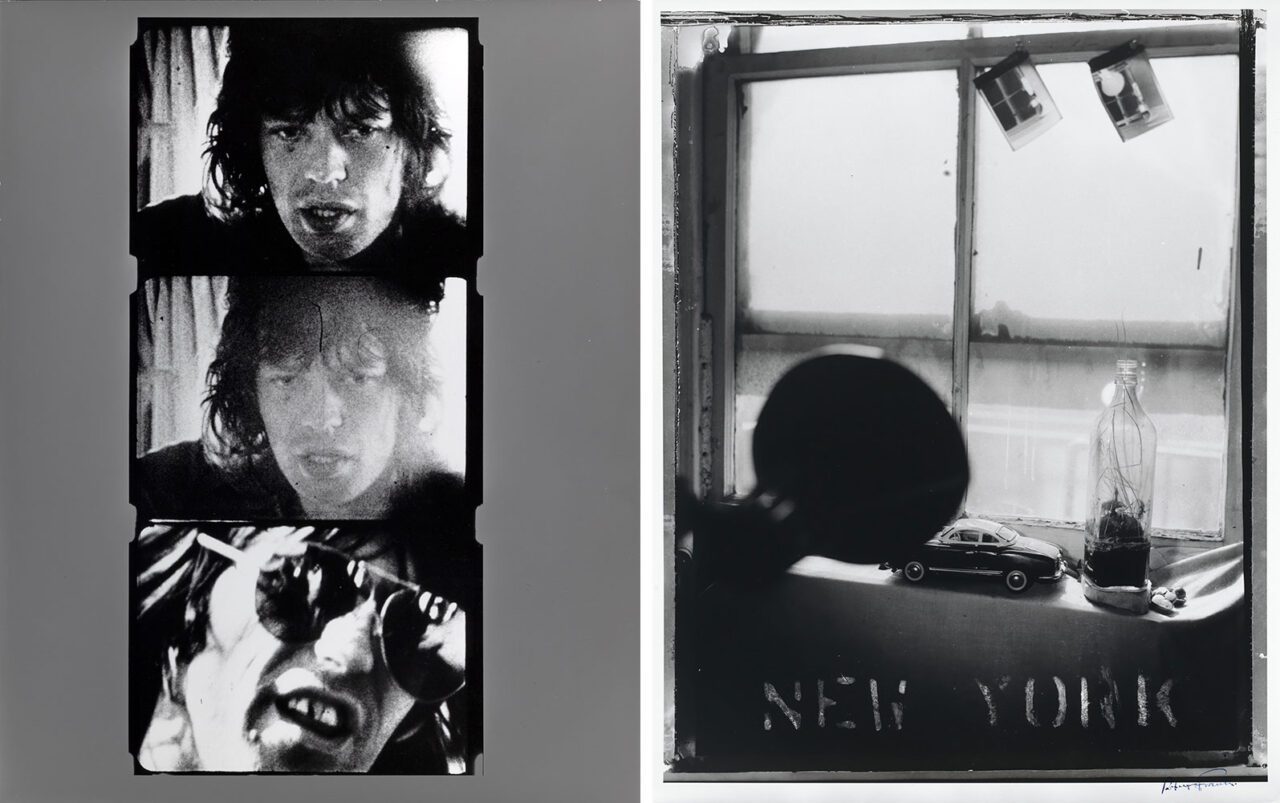

Right: Robert Frank. Pablo’s Bottle at Bleecker Street, New York City. 1973. Gelatin silver print, 19 13/16 × 15 7/8″ (50.3 × 40.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Promised gift of Michael Jesselson. © 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation