TRACES: Gerhard Richter

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Gerhard Richter (9/2/1932- ), who is widely regarded as one of the world’s leading contemporary artists. During a career spanning almost 60 years, the astonishing range of his work has become a defining characteristic, with painting at the centre of his development. Within that medium his scope and output have been prodigious and as a result Richter is seen by many as the greatest living painter. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Gerhard Richter (9/2/1932- ), who is widely regarded as one of the world’s leading contemporary artists. During a career spanning almost 60 years, the astonishing range of his work has become a defining characteristic, with painting at the centre of his development. Within that medium his scope and output have been prodigious and as a result Richter is seen by many as the greatest living painter. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

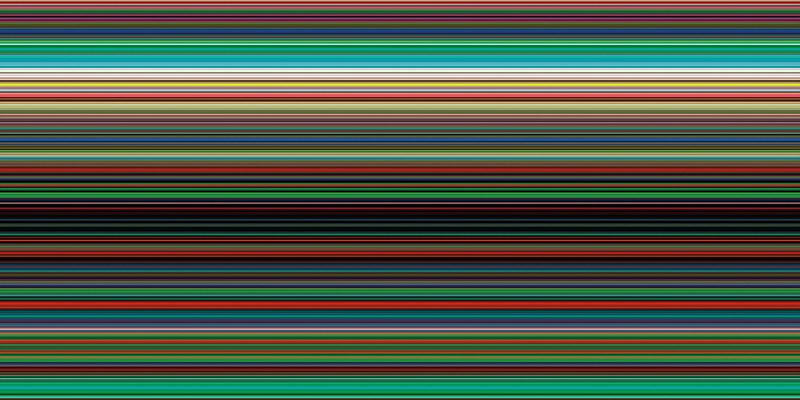

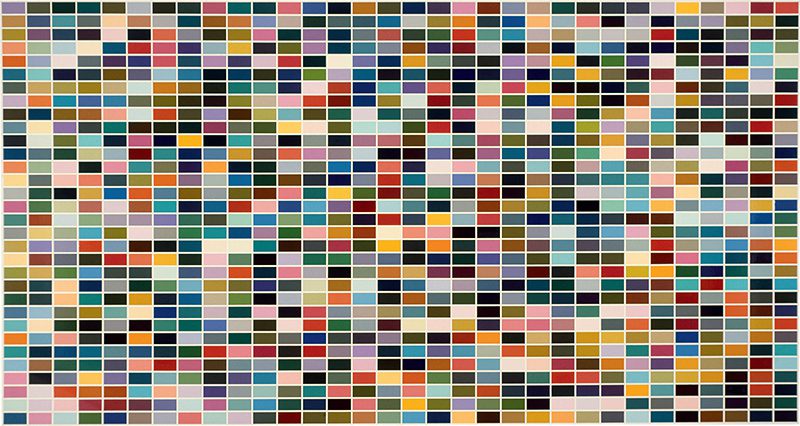

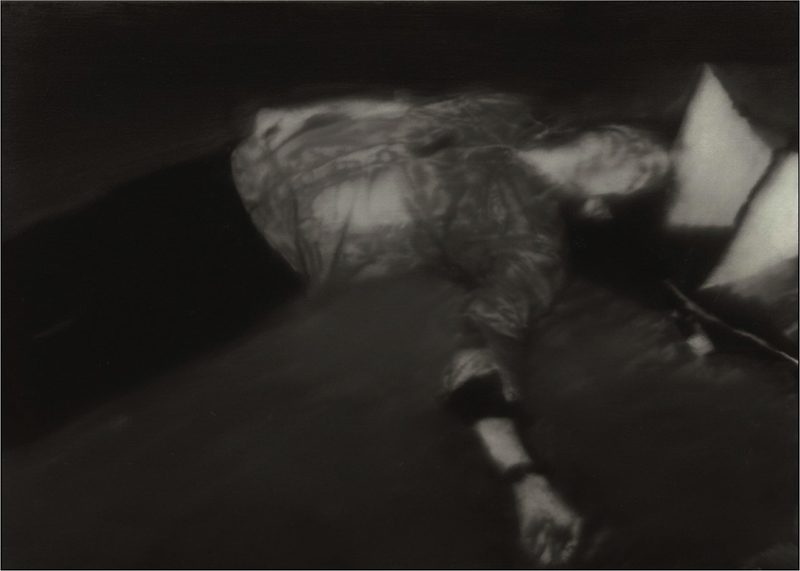

Gerhard Richter was born in Dresden, during the rise of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, or the Nazi Third Reich. Notably, some of Richter’s relatives were directly involved in the Nazi movement, namely his father, a schoolteacher, and an uncle. Richter’s mother, the daughter of a concert pianist, encouraged her son’s early talent for draftsmanship. While the years immediately following the end of World War II were in many ways difficult, Richter also has fond memories of this time, not least because he found he had access to books that had previously been forbidden under Nazi control. Speaking to Robert Storr, Richter explained: “It was very nasty, (but) when the Russians came to our village and expropriated the houses of the rich who had already left or were driven out, they made libraries for the people out of these houses. And that was fantastic”. In 1947, while still studying stenography, accounting and Russian at college in Zittau, Richter began attending evening classes in painting. In February 1950 he was taken on as an assistant set painter for the municipal theatre in Zittau. Richter had recently been involved with an amateur theatre group, so it was perhaps through this, or even, through friends from his evening classes, that he was aware of and disposed to the role at the theatre. His career in the theatre came to an abrupt end, however, when the he refused to do wall painting work on the theatre’s staircases, and was promptly dismissed. Beginning in 1951, Richter studied at the Kunstakademie, Dresden, where he painted murals and political banners commissioned by state-owned businesses. During this time, the East German communist regime imposed a Social Realist style on all practicing artists, this policy effectively turned art to the service of political propaganda. In keeping with this development, the government banned exhibitions of American Pop art and Fluxus. These circumstances severely limited Richter’s fledgling artistic style, as he was instructed to paint only landscapes in a manner heavily informed by pastoral romanticism. Having successfully completed his studies at the Academy in 1956, he was accepted onto a scheme run by the Academy for promising graduates. In exchange for teaching evening classes to the public, he received a studio and a modest income for the next three years. Richter’s break away from this mindset was in part inspired by a trip to documenta II in Kassel, West Germany, in 1959. Seeing works by Jackson Pollock, Jean Fautrier and Lucio Fontana among others made Richter aware that “There was something wrong with my whole way of thinking”, perceiving in their work the “Expression of a totally different and entirely new content”. In 1961, just prior to the government’s official completion of the Berlin Wall, Richter moved to Dusseldorf. Once again enrolling at the local Kunstakademie, Richter intended to work in a more uninhibited, avant-garde manner, in the process of rethinking his approach to art making, he purposely destroyed many of his early paintings from the ‘50s and the ‘60s.While continuing to paint in a realist manner, around 1961, Richter began using photographs, projecting and tracing images directly onto the canvas. Richter believed that he was, as an artist, “Not painting a particular person, but a picture that has nothing in common with the model”. Thus while he painted individuals from photographs, Richter’s replica images were often blurred and bore nothing distinctively identifiable about the subject, an effect that forced the viewer to consider the fundamental components of the painting itself, such as composition, color scheme, and so forth, rather than leaving the viewer to identify with, or be distracted by, a picture’s implied content or its emotional element of “humanity.” Eventually finding himself frustrated over whether to pursue abstraction or figuration, Richter decided to concentrate on the chance details that emerged from the painting process. Using the same method as employed in his representational paintings, Richter began blurring, scraping, and concealing various painted layers in his new canvases. In 1966, he created a series of grey paintings that featured compositional structure and paint application rather than realistic subject matter. Richter applied the paint in thick brushstrokes, or with rollers and an aggressive sweep of a squeegee (ironically, a tool commonly used for window cleaning and clarifying one’s scope of vision). In this particular body of work, Richter minimized the visual impact of realist imagery in favor of a spontaneous, gestural illusion of space. 1966 witnessed the introduction of a surprising new weapon to his painterly arsenal, geometric abstraction. When asked in 1986 whether this departure was in part influenced by the work of Blinky Palermo, Richter explained “Yes, it certainly did have something to do with Palermo and his interests, and later with Minimal Art as well; but when I painted my first colour charts in 1966, that had more to do with Pop Art…” In 1971, Richter became a professor at the Kunstakademie, Dusseldorf. This marks the beginning of his “color chart” paintings, in which he systematically applied square hues of solid color to large canvases. During this time, Richter received wide criticism for his express refusal to be identified with a specific artistic movement, as well as for his work’s apparent unwillingness to acknowledge various social and political issues pertaining to the WWII Nazi regime. Richter embraced the title, Abstract Painting, in 1976, as a generic one for all his subsequent canvases, a move that effectively forced viewers to interpret a given work without explanation provided by the artist. Richter found two main routes forward in 1977. The first perhaps marked a satisfactory conclusion to the inward logic of the monochrome and took the form of two sculptural pieces made of panes of glass and painted grey on one side, Richter’s second breakthrough of 1977 was the development of a substantial number of colourful abstract works he described simply as “Abstraktes Bild”. A series of works created between 1982 and 1983 with candles as their primary subject. Although they received surprisingly little attention when first exhibited in Germany these have come to be regarded as some of Richter’s most iconic works and have perhaps endeared him to the general public as much as to arts professionals. Landscapes were also to be a recurring theme in Richter’s Photo Paintings of the ‘80s, but it was another series of photo-paintings from the following year that was to prove to be his most significant body of work of the decade, and indeed, one of the most important of Richter’s career. Entitled “October 18, 1977”, the title of the series, refers to the date on which Gudrun Ensslin, Andreas Baader and Jan-Carl Raspe were found dead in their cells in Stuttgart-Stammheim prison. This was undoubtedly Richter’s most politically provocative body of work to date. Richter continued primarily producing abstract works interspersed with the occasional photo painting throughout the late ;90s. Speaking about this in 1999, Richter commented “I love figurative painting and find it very interesting. I’ve not done a lot of figurative work because I lack subjects. Abstract is something everyday for me, as natural as walking or breathing”. 2002 was a significant year for Richter due to his major retrospective exhibition “Forty Years of Painting” at MoMA in New York. Curated by Robert Storr, the exhibition featured 190 works, was one of the most comprehensive exhibitions of Richter’s works of his career. It was also the exhibition that confirmed Richter’s status as one of the leading artists in the world. In 2007 Richter completed arguably his largest commission, a major stained glass window for Cologne Cathedral to replace a window that had been destroyed during World War II. He had been invited to undertake the commission back in 2002 and had devoted considerable time to developing and completing the project in the following five years.

Gerhard Richter was born in Dresden, during the rise of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, or the Nazi Third Reich. Notably, some of Richter’s relatives were directly involved in the Nazi movement, namely his father, a schoolteacher, and an uncle. Richter’s mother, the daughter of a concert pianist, encouraged her son’s early talent for draftsmanship. While the years immediately following the end of World War II were in many ways difficult, Richter also has fond memories of this time, not least because he found he had access to books that had previously been forbidden under Nazi control. Speaking to Robert Storr, Richter explained: “It was very nasty, (but) when the Russians came to our village and expropriated the houses of the rich who had already left or were driven out, they made libraries for the people out of these houses. And that was fantastic”. In 1947, while still studying stenography, accounting and Russian at college in Zittau, Richter began attending evening classes in painting. In February 1950 he was taken on as an assistant set painter for the municipal theatre in Zittau. Richter had recently been involved with an amateur theatre group, so it was perhaps through this, or even, through friends from his evening classes, that he was aware of and disposed to the role at the theatre. His career in the theatre came to an abrupt end, however, when the he refused to do wall painting work on the theatre’s staircases, and was promptly dismissed. Beginning in 1951, Richter studied at the Kunstakademie, Dresden, where he painted murals and political banners commissioned by state-owned businesses. During this time, the East German communist regime imposed a Social Realist style on all practicing artists, this policy effectively turned art to the service of political propaganda. In keeping with this development, the government banned exhibitions of American Pop art and Fluxus. These circumstances severely limited Richter’s fledgling artistic style, as he was instructed to paint only landscapes in a manner heavily informed by pastoral romanticism. Having successfully completed his studies at the Academy in 1956, he was accepted onto a scheme run by the Academy for promising graduates. In exchange for teaching evening classes to the public, he received a studio and a modest income for the next three years. Richter’s break away from this mindset was in part inspired by a trip to documenta II in Kassel, West Germany, in 1959. Seeing works by Jackson Pollock, Jean Fautrier and Lucio Fontana among others made Richter aware that “There was something wrong with my whole way of thinking”, perceiving in their work the “Expression of a totally different and entirely new content”. In 1961, just prior to the government’s official completion of the Berlin Wall, Richter moved to Dusseldorf. Once again enrolling at the local Kunstakademie, Richter intended to work in a more uninhibited, avant-garde manner, in the process of rethinking his approach to art making, he purposely destroyed many of his early paintings from the ‘50s and the ‘60s.While continuing to paint in a realist manner, around 1961, Richter began using photographs, projecting and tracing images directly onto the canvas. Richter believed that he was, as an artist, “Not painting a particular person, but a picture that has nothing in common with the model”. Thus while he painted individuals from photographs, Richter’s replica images were often blurred and bore nothing distinctively identifiable about the subject, an effect that forced the viewer to consider the fundamental components of the painting itself, such as composition, color scheme, and so forth, rather than leaving the viewer to identify with, or be distracted by, a picture’s implied content or its emotional element of “humanity.” Eventually finding himself frustrated over whether to pursue abstraction or figuration, Richter decided to concentrate on the chance details that emerged from the painting process. Using the same method as employed in his representational paintings, Richter began blurring, scraping, and concealing various painted layers in his new canvases. In 1966, he created a series of grey paintings that featured compositional structure and paint application rather than realistic subject matter. Richter applied the paint in thick brushstrokes, or with rollers and an aggressive sweep of a squeegee (ironically, a tool commonly used for window cleaning and clarifying one’s scope of vision). In this particular body of work, Richter minimized the visual impact of realist imagery in favor of a spontaneous, gestural illusion of space. 1966 witnessed the introduction of a surprising new weapon to his painterly arsenal, geometric abstraction. When asked in 1986 whether this departure was in part influenced by the work of Blinky Palermo, Richter explained “Yes, it certainly did have something to do with Palermo and his interests, and later with Minimal Art as well; but when I painted my first colour charts in 1966, that had more to do with Pop Art…” In 1971, Richter became a professor at the Kunstakademie, Dusseldorf. This marks the beginning of his “color chart” paintings, in which he systematically applied square hues of solid color to large canvases. During this time, Richter received wide criticism for his express refusal to be identified with a specific artistic movement, as well as for his work’s apparent unwillingness to acknowledge various social and political issues pertaining to the WWII Nazi regime. Richter embraced the title, Abstract Painting, in 1976, as a generic one for all his subsequent canvases, a move that effectively forced viewers to interpret a given work without explanation provided by the artist. Richter found two main routes forward in 1977. The first perhaps marked a satisfactory conclusion to the inward logic of the monochrome and took the form of two sculptural pieces made of panes of glass and painted grey on one side, Richter’s second breakthrough of 1977 was the development of a substantial number of colourful abstract works he described simply as “Abstraktes Bild”. A series of works created between 1982 and 1983 with candles as their primary subject. Although they received surprisingly little attention when first exhibited in Germany these have come to be regarded as some of Richter’s most iconic works and have perhaps endeared him to the general public as much as to arts professionals. Landscapes were also to be a recurring theme in Richter’s Photo Paintings of the ‘80s, but it was another series of photo-paintings from the following year that was to prove to be his most significant body of work of the decade, and indeed, one of the most important of Richter’s career. Entitled “October 18, 1977”, the title of the series, refers to the date on which Gudrun Ensslin, Andreas Baader and Jan-Carl Raspe were found dead in their cells in Stuttgart-Stammheim prison. This was undoubtedly Richter’s most politically provocative body of work to date. Richter continued primarily producing abstract works interspersed with the occasional photo painting throughout the late ;90s. Speaking about this in 1999, Richter commented “I love figurative painting and find it very interesting. I’ve not done a lot of figurative work because I lack subjects. Abstract is something everyday for me, as natural as walking or breathing”. 2002 was a significant year for Richter due to his major retrospective exhibition “Forty Years of Painting” at MoMA in New York. Curated by Robert Storr, the exhibition featured 190 works, was one of the most comprehensive exhibitions of Richter’s works of his career. It was also the exhibition that confirmed Richter’s status as one of the leading artists in the world. In 2007 Richter completed arguably his largest commission, a major stained glass window for Cologne Cathedral to replace a window that had been destroyed during World War II. He had been invited to undertake the commission back in 2002 and had devoted considerable time to developing and completing the project in the following five years.