TRACES: Cindy Sherman

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Cindy Sherman (19/1/1954- ), by turning the camera on herself her work continually re-examines women’s roles in history and contemporary society, Sherman resists the notion that her photographs have an explicit narrative or message, leaving them untitled and largely open to interpretation. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Cindy Sherman (19/1/1954- ), by turning the camera on herself her work continually re-examines women’s roles in history and contemporary society, Sherman resists the notion that her photographs have an explicit narrative or message, leaving them untitled and largely open to interpretation. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

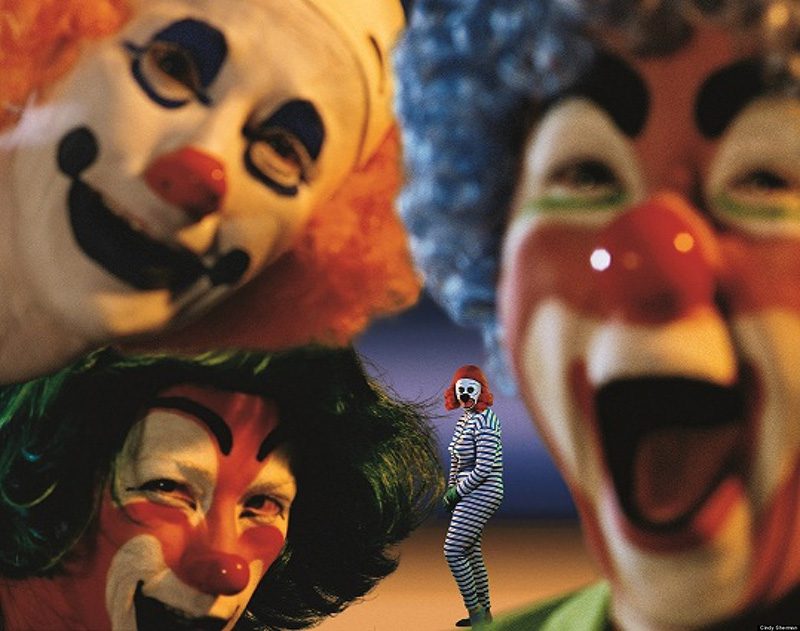

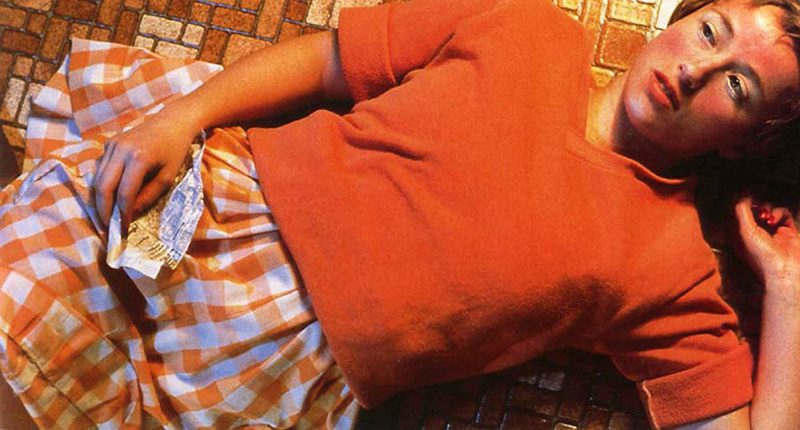

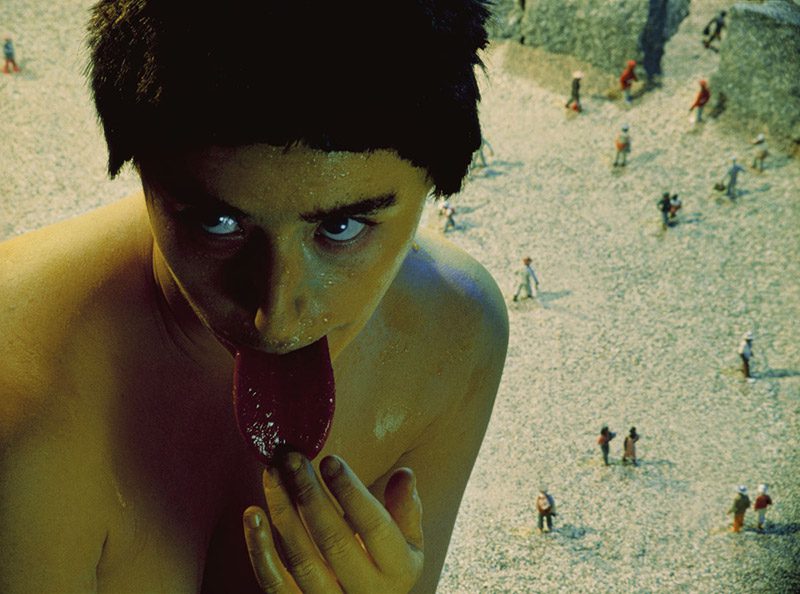

Although her parents shared a general disinterest in the arts, Cindy Sherman chose to study art in college, enrolling at the State University of New York, at Buffalo, in the early 70s. Sherman studied in Buffalo from 1972-76, she began as a painter, but she quickly found herself frustrated by what she considered certain limitations of the medium. Sherman has said that she felt that “There was nothing more to say (through painting). I was meticulously copying other art and then I realized I could just use a camera and put my time into an idea instead”. Sherman shifted her attention to photography. Although initially failing a required photography class, she later elected to repeat the course, which ignited her passion for the subject. During her studies, Sherman met fellow artists Robert Longo and Charles Clough, with whom she co-founded Hallwalls Center for Contemporary Art in 1974. In 1975, while still attending college, Cindy Sherman created her first series of five photographs entitled, Untitled A-E. Within these first photographs, Sherman attempts to alter her face with makeup and hats, attempting to take on different personas, such as a little girl in Untitled D, and a clown in Untitled A. During her studies, Sherman was exposed to Conceptual art and other progressive art movements and media under the widely influential art instructor, Barbara Jo Revelle. Upon graduation, Sherman moved to New York City to pursue her artistic career. In 1977, with her downtown residential and studio loft as her primary backdrop, Sherman began taking a series of photographs of herself, a project she would eventually refer to as the “Untitled Film Stills”. In this series, Sherman embodies the character of “Everywoman”. Re-fashioning herself repeatedly into the guise of various female archetypes, Sherman played the girly pin-up, the film noir siren, the housewife, the prostitute, and the noble damsel in distress. The black-and-white series occupied her for about three years, so that by 1980 Sherman had virtually exhausted a myriad of seemingly timeless cliches referring to the “feminine”. She has said “Everyone thinks these are self-portraits but they aren’t meant to be. I just use myself as a model because I know I can push myself to extremes, make each shot as ugly or goofy or silly as possible”. With the debut of Untitled Film Stills, Sherman secured her position in the New York art world, leading to her first solo show at the non-profit exhibition space, The Kitchen. Shortly after, she was commissioned to create a centerfold image for Artforum magazine. Photos of a pink-robe-clad Sherman were ultimately deemed too racy by editor Ingrid Sischy and rejected. There is no knowing whether a subsequent series shot from 1985 to 1989, Disasters and Fairy Tales was in some sense a response to that act of rejection, but, notably, it is a much darker endeavor than its prettified predecessor. Its gloomy palette and scenes strewn with vomit and mold challenged viewers to find beauty in the ugly and the unqualified grotesque. Sherman’s next series took on the hallowed subject of the art tableau. History Portraits again presented Sherman-as-model, but this time she assumed the air of European art history’s most famous “leading ladies.” Living in Europe at the time of its creation, Sherman drew inspiration from the West’s great museums Sherman’s next career move was to a raunchy pornographic depiction of individuals called the Sex Pictures. Using mannequins and body parts form medical catalogues, she constructs hybrid dolls. Rather then showing the dolls having sex, Sherman proudly shows the sex. Sherman created these works in response to the controversy over the National Endowment for the arts and the debates over the constitute obscenity in the arts. Over the last decade, Sherman dons clown’s make-up in a series of still photography (2003) and, even more recently, she explored carefully staged female “Suburban” identities. In the latter series, Sherman photographed herself in various states of awkward make-up, superimposing stodgy, highly self-conscious portraits over contrived domestic and faux-monumental backdrops.