TRACES: Andreas Gursky

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the German Photographer Andreas Gursky (15/1/1955- ), who is widely regarded as one of the world’s foremost contemporary photographers. Among the hallmarks of his work are his use of color, his supersize formats and his excessive deployment of digital image processing. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the German Photographer Andreas Gursky (15/1/1955- ), who is widely regarded as one of the world’s foremost contemporary photographers. Among the hallmarks of his work are his use of color, his supersize formats and his excessive deployment of digital image processing. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

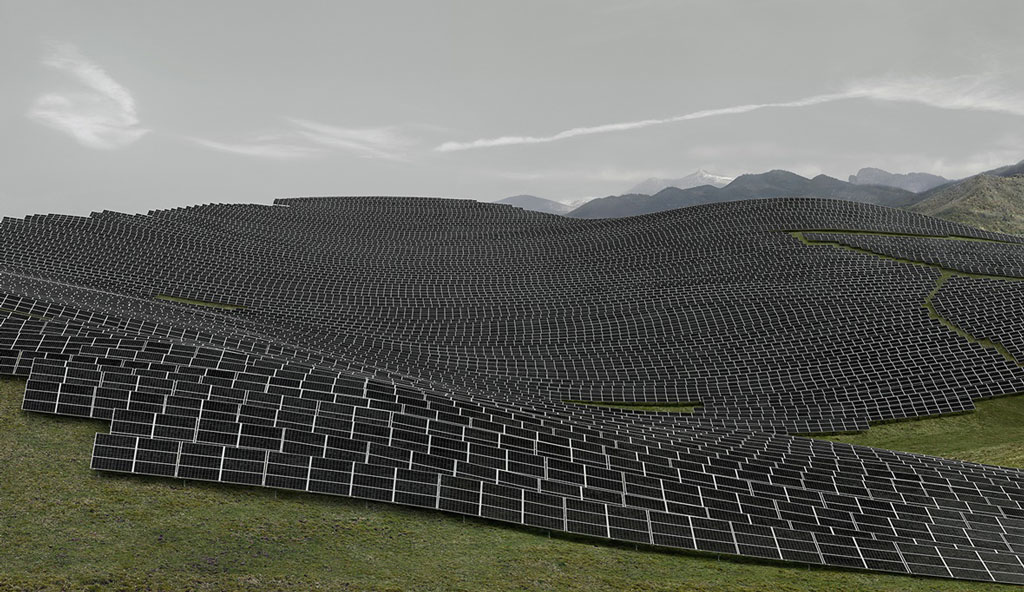

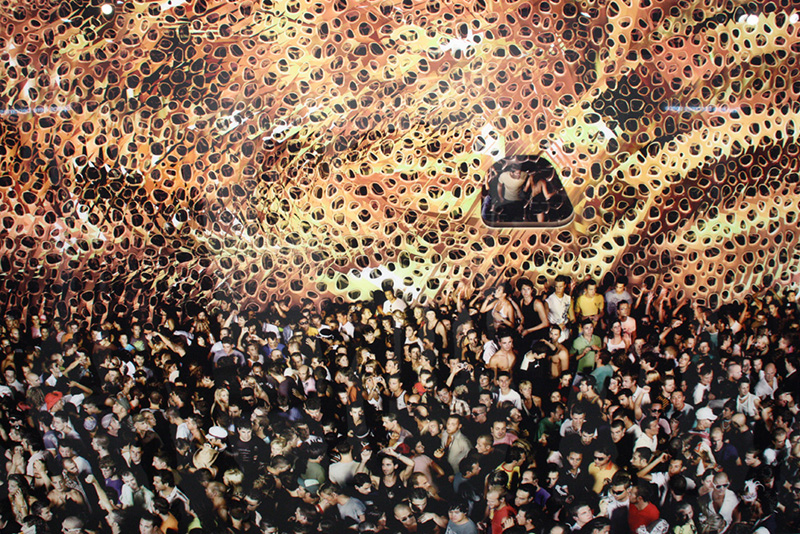

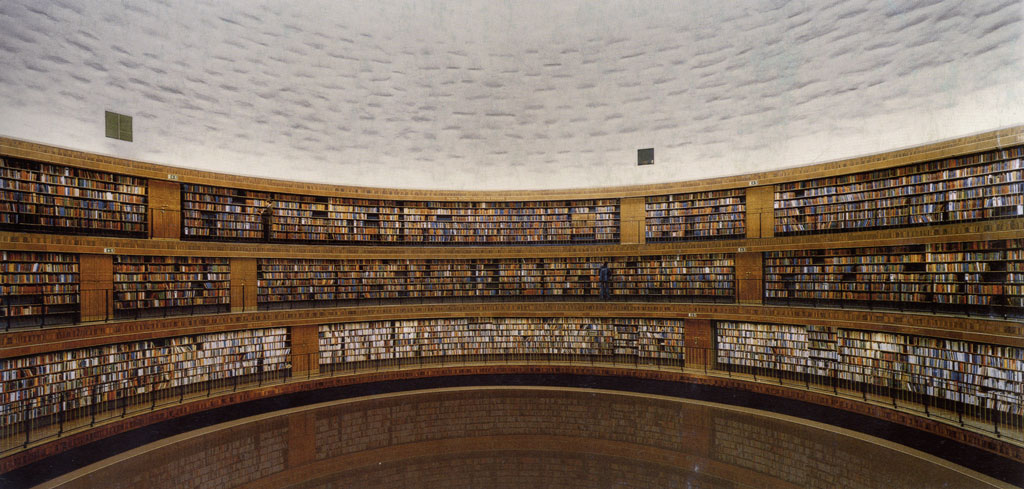

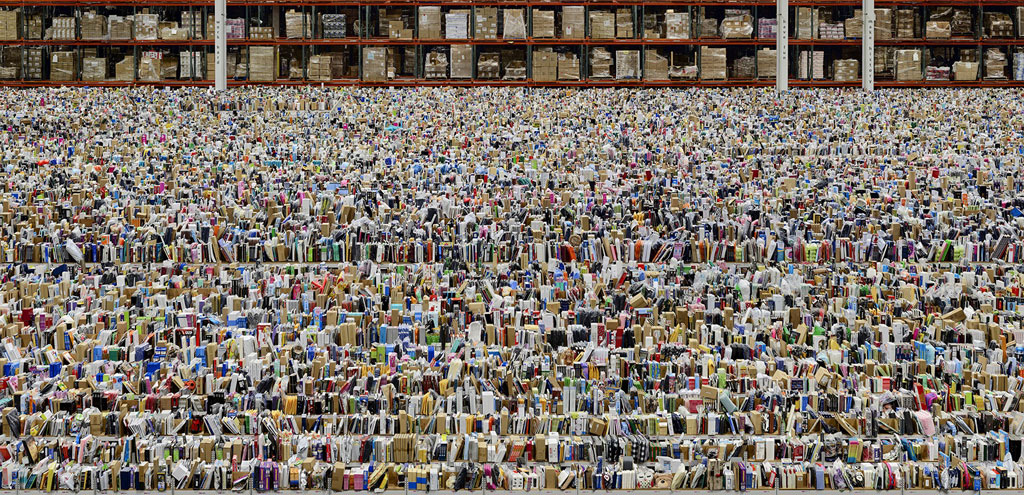

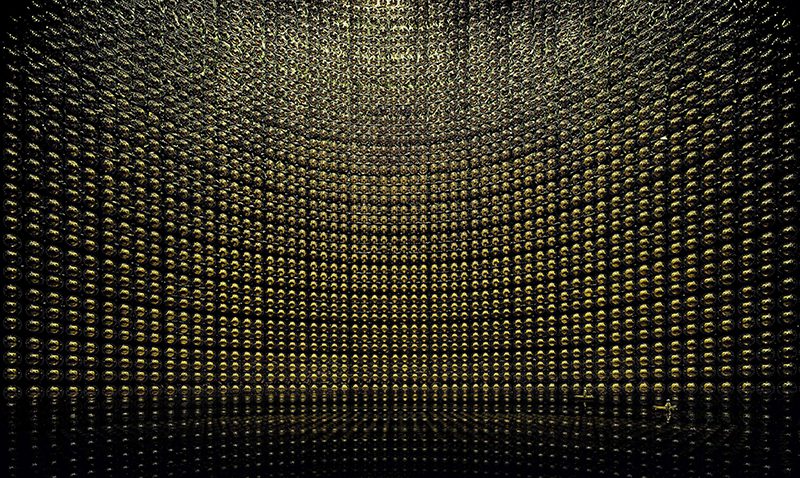

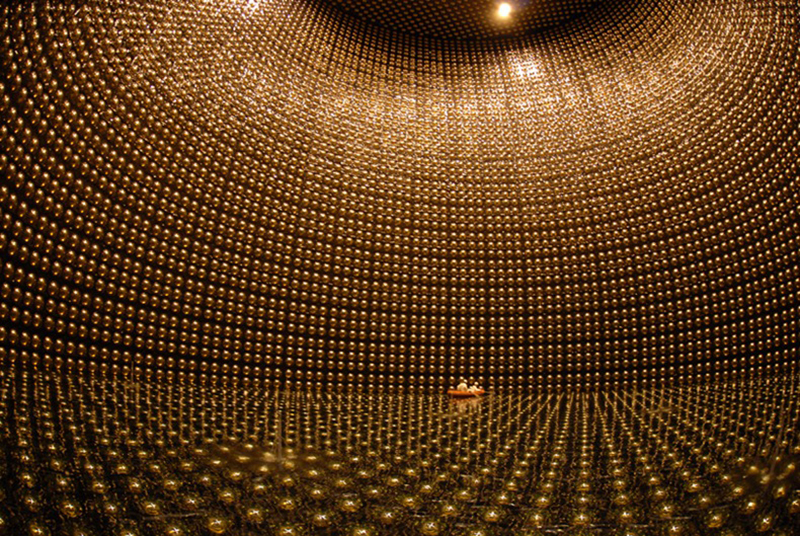

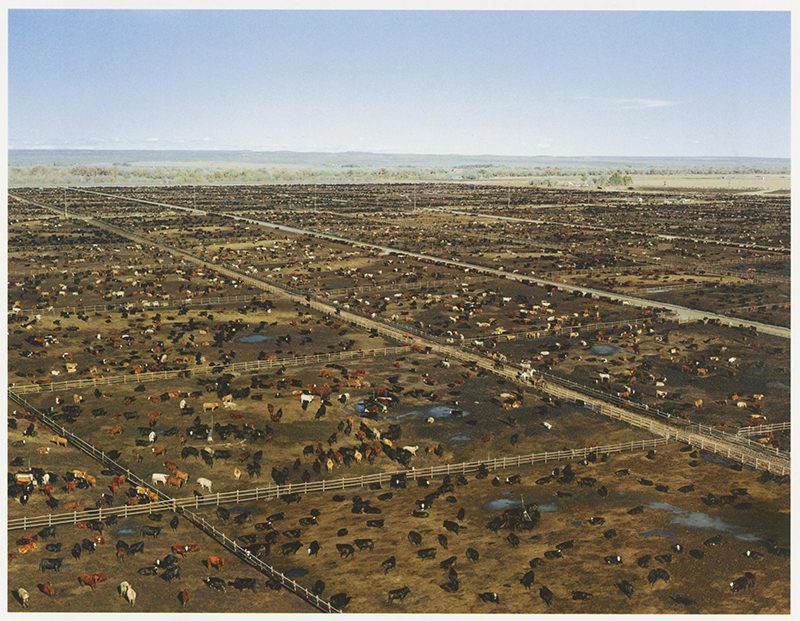

Gursky was born in Leipzig, Germany in 1955. His family relocated to West Germany, moving to Essen and then Düsseldorf by the end of 1957. We might say that Andreas Gursky learned photography three times. Born in Leipzig, a town of the former East Germany. His family relocated to West Germany, by the end of 1957, he grew up in Düsseldorf, the only child of a successful commercial photographer, learning the tricks of that trade before he had finished high school. In the late ’70s, he spent two years in nearby Essen at the Folkwangschule, which Otto Steinert had established as West Germany’s leading training ground for professional photographers. At Essen, Gursky encountered photography’s documentary tradition, a sophisticated art of unembellished observation, whose earnest outlook was remote from the artificial enticements of commercial work. Finally, in the early ‘80s, he studied at the Staatliche Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf, which thanks to artists such as Joseph Beuys, Sigmar Polke, and Gerhard Richter had become the hotbed of Germany’s vibrant postwar avant-garde. There Gursky learned the ropes of the art world and mastered the rigorous method of Bernd and Hilla Becher, a photographic team known for their distinctive, dispassionate method of systematically cataloging industrial machinery and architecture. The Photos of Bernd and Hilla Becherhad achieved prominence within the Conceptual and Minimal Art movements. Other notable influences are the British landscape photographer John Davies, whose highly detailed high vantage point images had a strong effect on the street level photographs Gursky was then making, and to a lesser degree the American photographer Joel Sternfeld. During his training, Gursky used the traditional formats (30 or 36 inches). From 1988 he introduces large formats, and from 2000 onwards he even proceeds to combining sheets to produce giant prints up to five meter. When Gursky began to win recognition in the late ‘80s, his photography was interpreted as an extension of his teachers’ aesthetic. But the full range of Gursky’s photographic educations has figured in his mature work, enabling him to outgrow all three of them. His photographs, big, bold, rich in color and detailconstitute one of the most original achievements of the past decade and, for all the panache of his signature style, one of the most complex. Before the 1990s, Gursky did not digitally manipulate his images. In the years since, Gursky has been frank about his reliance on computers to edit and enhance his pictures, creating an art of spaces larger than the subjects photographed. Is said that Gursky uses 100 ASA Fuji film in two large-format Linhof cameras that are positioned side by side, one with a slight wide-angle lens, the other with a standard one. Exposure time: 1/8, f-stop 5.6 to 8. He needs this for depth of field, and the relatively low-speed film for the resolution. Any occasional blurred movement is discarded later in the process. He gains speed by underexposing the film stock one f-stop, and has it developed using push processing. After scans his negatives to work on them digitally. The most drastic digital intervention is the combination of distinct shots in one and the image. The number of shots may vary from two “Montparnasse” (1993) to some dozen in images like “Stockholders Meeting” (2001). In “99 cent II Diptychon” (1999) also the reflection of the merchandise on the ceiling is added, and in “Mayday V” (2001) some stores are added to the Westfalenhalle. Such digital collage necessitates the above mentioned homogenising of colour, because Gursky’s collages are not collages in the traditional sense of the word. In traditional collage, heterogeneous elements are combined to an estranging whole. In his construction of a new reality, Gursky does not hesitate, finally, to remove unwanted elements from his photos. In his “Rhein II” (1999) every trace of industrialisation is eliminated, so that it seems as if a virgin river streams through unspoilt nature, and in “Stockholm public library” (1999) the floor and an elevator are omitted. The perspective in many of Gursky’s photographs is drawn from an elevated vantage point. This position enables the viewer to encounter scenes, encompassing both centre and periphery, which are ordinarily beyond reach. Visually, Gursky is drawn to large, anonymous, man-made spaces, high-rise facades at night, office lobbies, stock exchanges, the interiors of big shops. Gursky tends to focus on crowds of people and the places where they assemble, and on the structures of the globalised world with its production, trade, consumption and leisure. In one of his most recent cycles of photographs, Pyongyang , he takes this theme one step further, casting his gaze on a country that is one of the last unmistakably non-globalised societies in the world. This is no everyday scenario, but an organised mass event with an ideological back ground. Gursky, however, does not use the images to make a statement about the political background of the event. Instead, he uses them as visual raw material to be processed according to his own distinctive compositional approach.

Gursky was born in Leipzig, Germany in 1955. His family relocated to West Germany, moving to Essen and then Düsseldorf by the end of 1957. We might say that Andreas Gursky learned photography three times. Born in Leipzig, a town of the former East Germany. His family relocated to West Germany, by the end of 1957, he grew up in Düsseldorf, the only child of a successful commercial photographer, learning the tricks of that trade before he had finished high school. In the late ’70s, he spent two years in nearby Essen at the Folkwangschule, which Otto Steinert had established as West Germany’s leading training ground for professional photographers. At Essen, Gursky encountered photography’s documentary tradition, a sophisticated art of unembellished observation, whose earnest outlook was remote from the artificial enticements of commercial work. Finally, in the early ‘80s, he studied at the Staatliche Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf, which thanks to artists such as Joseph Beuys, Sigmar Polke, and Gerhard Richter had become the hotbed of Germany’s vibrant postwar avant-garde. There Gursky learned the ropes of the art world and mastered the rigorous method of Bernd and Hilla Becher, a photographic team known for their distinctive, dispassionate method of systematically cataloging industrial machinery and architecture. The Photos of Bernd and Hilla Becherhad achieved prominence within the Conceptual and Minimal Art movements. Other notable influences are the British landscape photographer John Davies, whose highly detailed high vantage point images had a strong effect on the street level photographs Gursky was then making, and to a lesser degree the American photographer Joel Sternfeld. During his training, Gursky used the traditional formats (30 or 36 inches). From 1988 he introduces large formats, and from 2000 onwards he even proceeds to combining sheets to produce giant prints up to five meter. When Gursky began to win recognition in the late ‘80s, his photography was interpreted as an extension of his teachers’ aesthetic. But the full range of Gursky’s photographic educations has figured in his mature work, enabling him to outgrow all three of them. His photographs, big, bold, rich in color and detailconstitute one of the most original achievements of the past decade and, for all the panache of his signature style, one of the most complex. Before the 1990s, Gursky did not digitally manipulate his images. In the years since, Gursky has been frank about his reliance on computers to edit and enhance his pictures, creating an art of spaces larger than the subjects photographed. Is said that Gursky uses 100 ASA Fuji film in two large-format Linhof cameras that are positioned side by side, one with a slight wide-angle lens, the other with a standard one. Exposure time: 1/8, f-stop 5.6 to 8. He needs this for depth of field, and the relatively low-speed film for the resolution. Any occasional blurred movement is discarded later in the process. He gains speed by underexposing the film stock one f-stop, and has it developed using push processing. After scans his negatives to work on them digitally. The most drastic digital intervention is the combination of distinct shots in one and the image. The number of shots may vary from two “Montparnasse” (1993) to some dozen in images like “Stockholders Meeting” (2001). In “99 cent II Diptychon” (1999) also the reflection of the merchandise on the ceiling is added, and in “Mayday V” (2001) some stores are added to the Westfalenhalle. Such digital collage necessitates the above mentioned homogenising of colour, because Gursky’s collages are not collages in the traditional sense of the word. In traditional collage, heterogeneous elements are combined to an estranging whole. In his construction of a new reality, Gursky does not hesitate, finally, to remove unwanted elements from his photos. In his “Rhein II” (1999) every trace of industrialisation is eliminated, so that it seems as if a virgin river streams through unspoilt nature, and in “Stockholm public library” (1999) the floor and an elevator are omitted. The perspective in many of Gursky’s photographs is drawn from an elevated vantage point. This position enables the viewer to encounter scenes, encompassing both centre and periphery, which are ordinarily beyond reach. Visually, Gursky is drawn to large, anonymous, man-made spaces, high-rise facades at night, office lobbies, stock exchanges, the interiors of big shops. Gursky tends to focus on crowds of people and the places where they assemble, and on the structures of the globalised world with its production, trade, consumption and leisure. In one of his most recent cycles of photographs, Pyongyang , he takes this theme one step further, casting his gaze on a country that is one of the last unmistakably non-globalised societies in the world. This is no everyday scenario, but an organised mass event with an ideological back ground. Gursky, however, does not use the images to make a statement about the political background of the event. Instead, he uses them as visual raw material to be processed according to his own distinctive compositional approach.