TRACES: Jean-Michel Basquiat

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (22/12/1960-12/8/1988). Basquiat’s work is an example of how the American artists of the ‘80s could reintroduce the human figure in their work after the wide success of Minimalism and Conceptualism, thus establishing a dialogue with the more distant tradition of ‘50s Abstract Expressionism. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (22/12/1960-12/8/1988). Basquiat’s work is an example of how the American artists of the ‘80s could reintroduce the human figure in their work after the wide success of Minimalism and Conceptualism, thus establishing a dialogue with the more distant tradition of ‘50s Abstract Expressionism. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

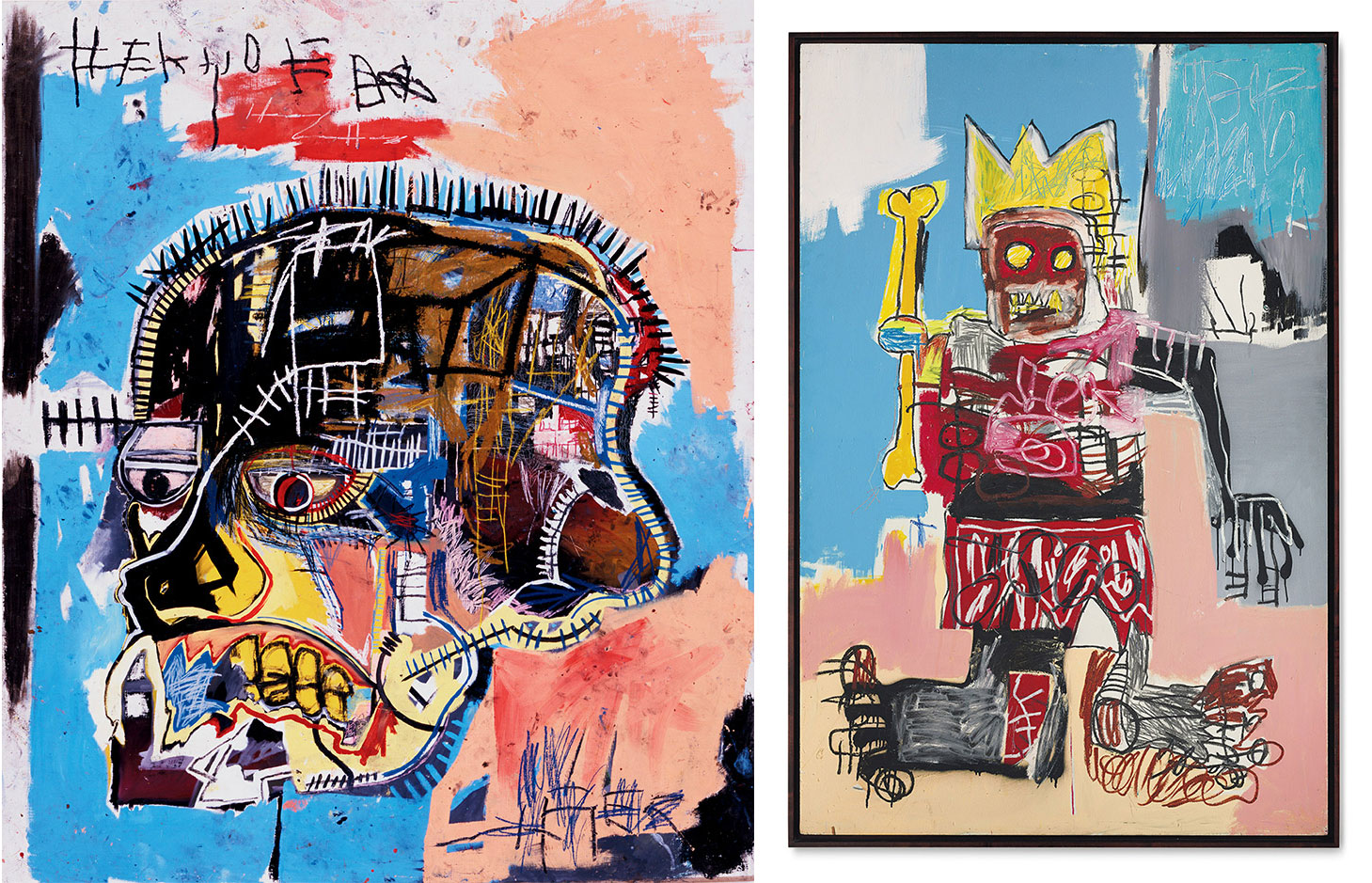

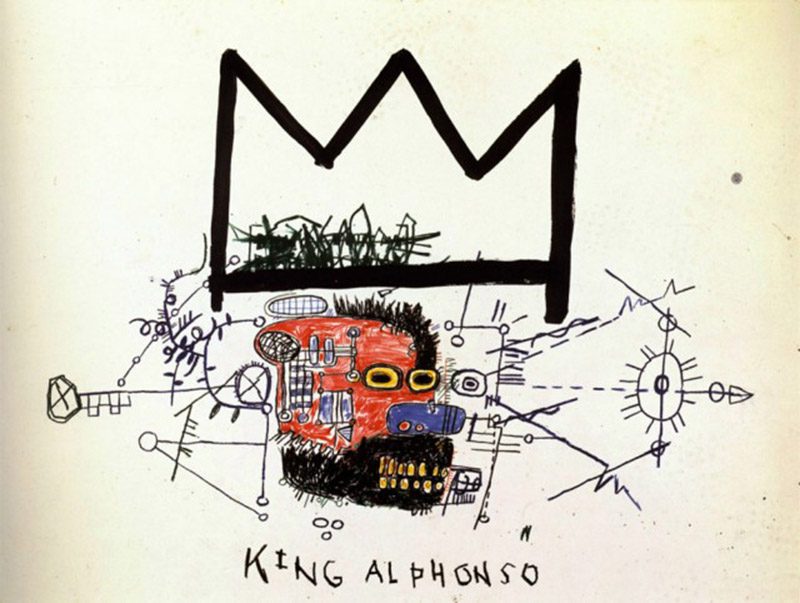

By Dimitris Lempesis

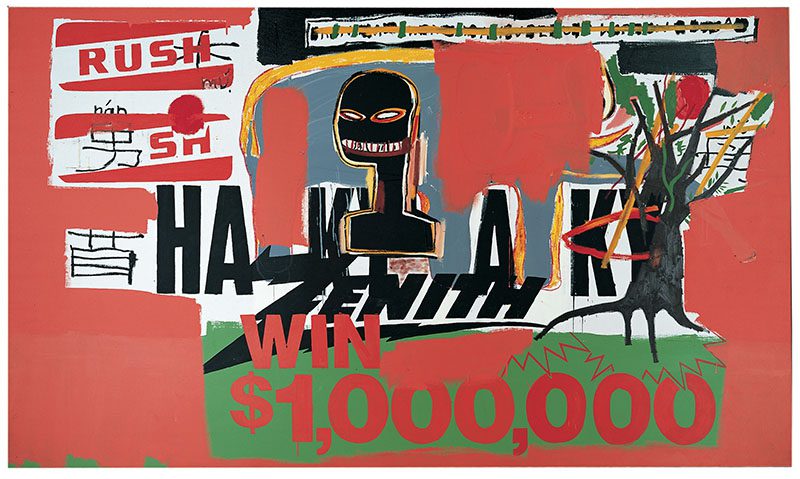

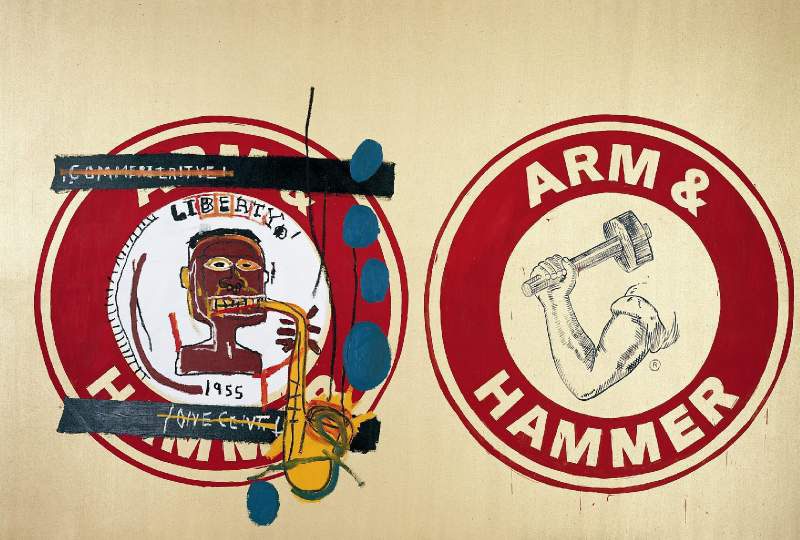

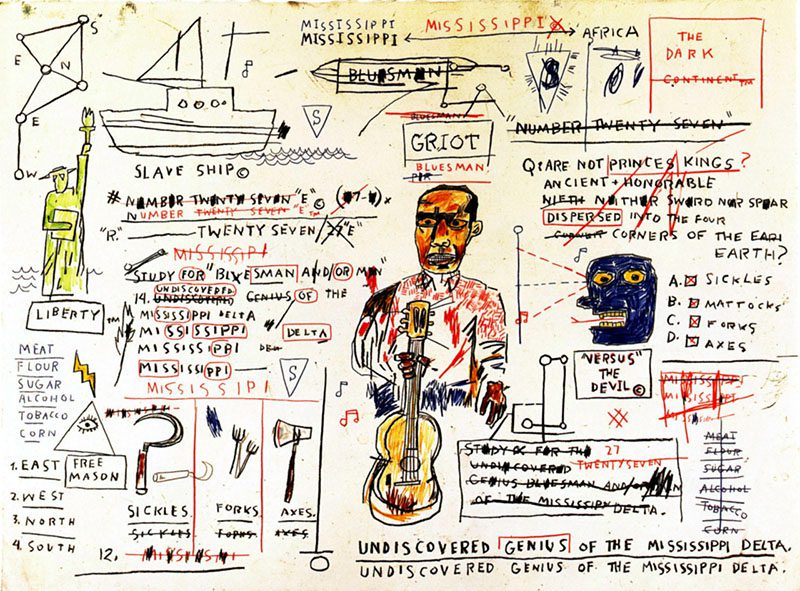

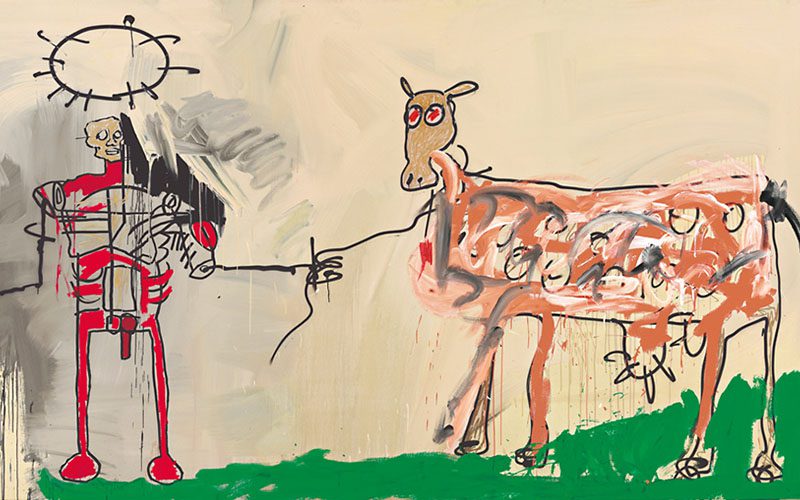

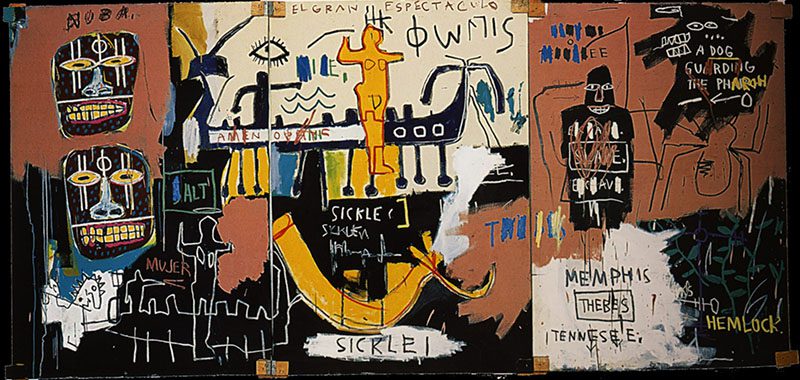

Jean-Michel Basquiat was born in Brooklyn, New York. His mother was of Puerto Rican heritage, and his father a Haitian immigrant. Basquiat displayed a talent for art in early childhood, learning to draw and paint with his mother’s encouragement. In September 1968, when Basquiat was about eight, he was hit by a car while playing in the street. His arm was broken and he suffered several internal injuries, and he eventually underwent a splenectomy. While he was recuperating from his injuries, his mother brought him the Gray’s Anatomy book, this book would prove to be influential in his future artistic outlook. His parents separated that year and he and his sisters were raised by their father. After his parents’ divorce, Basquiat lived alone with his father, his mother having been determined unfit to care for him owing to mental instability. Claiming physical and emotional abuse, Basquiat eventually ran away from home and was adopted by a friend’s family. Although he attended school sporadically in New York and Puerto Rico, he finally dropped out of Edward R. Murrow High School, in Brooklyn, in September 1978, at the age of 18.Basquiat’s art was fundamentally rooted in the ‘70s, New York City graffiti movement. In 1972, he and an artist friend, Al Diaz, started spray-painting buildings in Lower Manhattan under the name SAMO, an acronym for “Same Old Shit”. With its anti-establishment, anti-religion, anti-politics credo packaged in an ultra-contemporary format, SAMO soon received media attention from the counter-culture press, among them the Village Voice. When Basquiat and Diaz had a falling out, Basquiat ended the project with the terse message “SAMO IS DEAD”, which appeared on the facade of many SoHo art galleries and downtown buildings. After taking note of the mantra, contemporary street artist, Keith Haring, staged a mock wake for SAMO at his Club 57. Homeless and sleeping on park benches, Basquiat supported himself by panhandling, dealing drugs, and peddling hand-painted postcards and T-shirts. Basquiat frequented the Mudd Club and Club 57-both teeming with New York City’s artistic elite. During his stint as a punk rocker, he appeared as a nightclub DJ in the Blondie music video, Rapture. After inclusion of his work in the historic, punk-art Times Square Show of June 1980, Basquiat had his first solo exhibition at the Annina Nosei Gallery, in SoHo (1982). Basquiat’s rise to wider recognition coincided with the arrival, in New York, of the German Neo-Expressionist movement, which provided a congenial forum for his own street-smart, curbside expressionism. Basquiat began exhibiting regularly with artists like Julian Schnabel and David Salle, all of whom were reacting, to one or another degree, against the recent historical dominance of Conceptualism and Minimalism. Neo-Expressionism marked the return of painting and the re-emergence of the human figure. Images of the African Diaspora and classic Americana punctuated Basquiat’s work at this time, some of which was featured at the prestigious Mary Boone Gallery in solo shows in the mid ‘80s. 1982 was a banner year for Basquait, as he opened six solo exhibitions worldwide and became the youngest artist ever to be included in Documenta. During this time, Basquiat created some 200 art works and developed a signature motif, a heroic, crowned black oracle figure. Dizzy Gillespie, Sugar Ray Robinson, and Muhammad Ali were among Basquiat’s inspirational precursors, sketchy and Neo-Expressionist in appearance, the portraits captured the essence rather than the physical likeness of their subjects. The ferocity of Basquiat’s technique, those slashes of paint and dynamic dashes of line, presumably revealed his subjects’ inner-self, their hidden feelings, and their deepest desires. In keeping with a wider Black Renaissance in the New York art world of the same era, another epic figure, the West African griot, also features heavily in Basquiat’s work of the Neo-Expressionist era. The griot propagated community history in West African culture through storytelling and song, and he is typically depicted by Basquiat with a grimace and squinting elliptical eyes, their gaze fixed securely on the observer. At the suggestion of Swiss dealer Bruno Bischofberger, Warhol and Basquiat worked on a series of collaborative paintings between 1983 and 1985. In the case of “Olympic Rings”, Warhol made several variations of the Olympic five-ring symbol, rendered in the original primary colors. Basquiat responded to the abstract, stylized logos with his oppositional graffiti style. When Andy Warhol died on 22/2/87, Basquiat became increasingly isolated, and his heroin addiction and depression grew more severe. Despite an attempt at sobriety during a trip to Maui, Hawaii, he died on 12/8/88, of a heroin overdose at his art studio on Great Jones Street in Manhattan. In his short and largely troubled life, Jean-Michel Basquiat nonetheless came to play an important and historic role in the rise of Punk Art and Neo-Expressionism in the New York art scene. While the larger public latched on to the superficial exoticism of his work and were captivated by his overnight celebrity, his art, often described inaccurately as “Naif” and “Ethnically gritty”, held important connections to expressive precursors, such as Jean Dubuffet and Cy Twombly.

Jean-Michel Basquiat was born in Brooklyn, New York. His mother was of Puerto Rican heritage, and his father a Haitian immigrant. Basquiat displayed a talent for art in early childhood, learning to draw and paint with his mother’s encouragement. In September 1968, when Basquiat was about eight, he was hit by a car while playing in the street. His arm was broken and he suffered several internal injuries, and he eventually underwent a splenectomy. While he was recuperating from his injuries, his mother brought him the Gray’s Anatomy book, this book would prove to be influential in his future artistic outlook. His parents separated that year and he and his sisters were raised by their father. After his parents’ divorce, Basquiat lived alone with his father, his mother having been determined unfit to care for him owing to mental instability. Claiming physical and emotional abuse, Basquiat eventually ran away from home and was adopted by a friend’s family. Although he attended school sporadically in New York and Puerto Rico, he finally dropped out of Edward R. Murrow High School, in Brooklyn, in September 1978, at the age of 18.Basquiat’s art was fundamentally rooted in the ‘70s, New York City graffiti movement. In 1972, he and an artist friend, Al Diaz, started spray-painting buildings in Lower Manhattan under the name SAMO, an acronym for “Same Old Shit”. With its anti-establishment, anti-religion, anti-politics credo packaged in an ultra-contemporary format, SAMO soon received media attention from the counter-culture press, among them the Village Voice. When Basquiat and Diaz had a falling out, Basquiat ended the project with the terse message “SAMO IS DEAD”, which appeared on the facade of many SoHo art galleries and downtown buildings. After taking note of the mantra, contemporary street artist, Keith Haring, staged a mock wake for SAMO at his Club 57. Homeless and sleeping on park benches, Basquiat supported himself by panhandling, dealing drugs, and peddling hand-painted postcards and T-shirts. Basquiat frequented the Mudd Club and Club 57-both teeming with New York City’s artistic elite. During his stint as a punk rocker, he appeared as a nightclub DJ in the Blondie music video, Rapture. After inclusion of his work in the historic, punk-art Times Square Show of June 1980, Basquiat had his first solo exhibition at the Annina Nosei Gallery, in SoHo (1982). Basquiat’s rise to wider recognition coincided with the arrival, in New York, of the German Neo-Expressionist movement, which provided a congenial forum for his own street-smart, curbside expressionism. Basquiat began exhibiting regularly with artists like Julian Schnabel and David Salle, all of whom were reacting, to one or another degree, against the recent historical dominance of Conceptualism and Minimalism. Neo-Expressionism marked the return of painting and the re-emergence of the human figure. Images of the African Diaspora and classic Americana punctuated Basquiat’s work at this time, some of which was featured at the prestigious Mary Boone Gallery in solo shows in the mid ‘80s. 1982 was a banner year for Basquait, as he opened six solo exhibitions worldwide and became the youngest artist ever to be included in Documenta. During this time, Basquiat created some 200 art works and developed a signature motif, a heroic, crowned black oracle figure. Dizzy Gillespie, Sugar Ray Robinson, and Muhammad Ali were among Basquiat’s inspirational precursors, sketchy and Neo-Expressionist in appearance, the portraits captured the essence rather than the physical likeness of their subjects. The ferocity of Basquiat’s technique, those slashes of paint and dynamic dashes of line, presumably revealed his subjects’ inner-self, their hidden feelings, and their deepest desires. In keeping with a wider Black Renaissance in the New York art world of the same era, another epic figure, the West African griot, also features heavily in Basquiat’s work of the Neo-Expressionist era. The griot propagated community history in West African culture through storytelling and song, and he is typically depicted by Basquiat with a grimace and squinting elliptical eyes, their gaze fixed securely on the observer. At the suggestion of Swiss dealer Bruno Bischofberger, Warhol and Basquiat worked on a series of collaborative paintings between 1983 and 1985. In the case of “Olympic Rings”, Warhol made several variations of the Olympic five-ring symbol, rendered in the original primary colors. Basquiat responded to the abstract, stylized logos with his oppositional graffiti style. When Andy Warhol died on 22/2/87, Basquiat became increasingly isolated, and his heroin addiction and depression grew more severe. Despite an attempt at sobriety during a trip to Maui, Hawaii, he died on 12/8/88, of a heroin overdose at his art studio on Great Jones Street in Manhattan. In his short and largely troubled life, Jean-Michel Basquiat nonetheless came to play an important and historic role in the rise of Punk Art and Neo-Expressionism in the New York art scene. While the larger public latched on to the superficial exoticism of his work and were captivated by his overnight celebrity, his art, often described inaccurately as “Naif” and “Ethnically gritty”, held important connections to expressive precursors, such as Jean Dubuffet and Cy Twombly.