TRACES: Felix Gonzalez-Torres

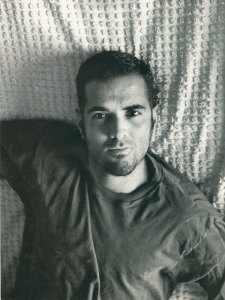

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the Cuban Artist, Felix Gonzalez-Torres (26/11/1957-9/1/1996), known for work in a variety of media that addresses issues of identity, desire, originality, loss, the metaphor of journey, and the private versus the public domain. Like many artists of the 1980s, Gonzalez-Torres used the postmodern strategy of appropriating ready-made motifs and objects to create his art, thereby challenging the idea of the unique art object that was so much a hallmark of Modernism. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the Cuban Artist, Felix Gonzalez-Torres (26/11/1957-9/1/1996), known for work in a variety of media that addresses issues of identity, desire, originality, loss, the metaphor of journey, and the private versus the public domain. Like many artists of the 1980s, Gonzalez-Torres used the postmodern strategy of appropriating ready-made motifs and objects to create his art, thereby challenging the idea of the unique art object that was so much a hallmark of Modernism. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

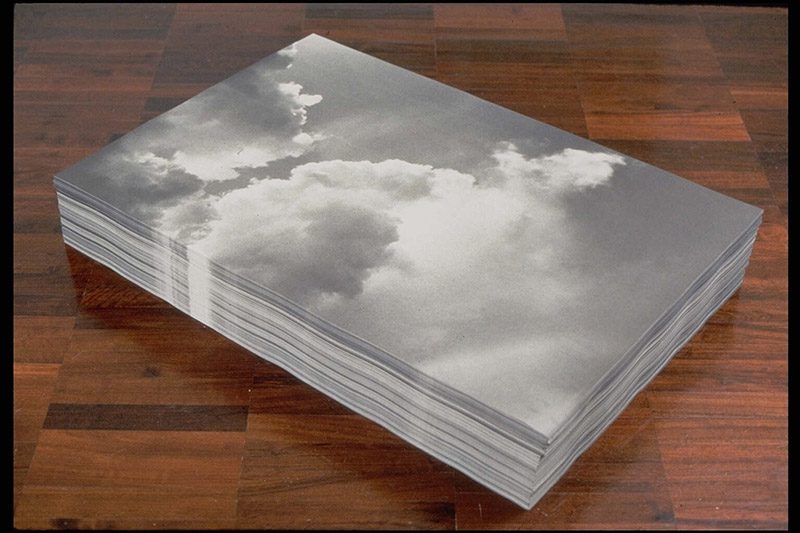

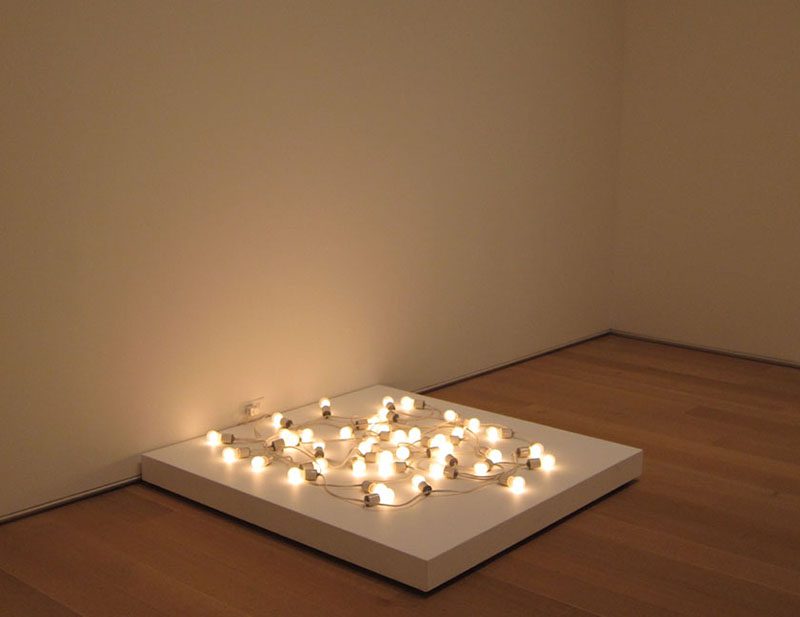

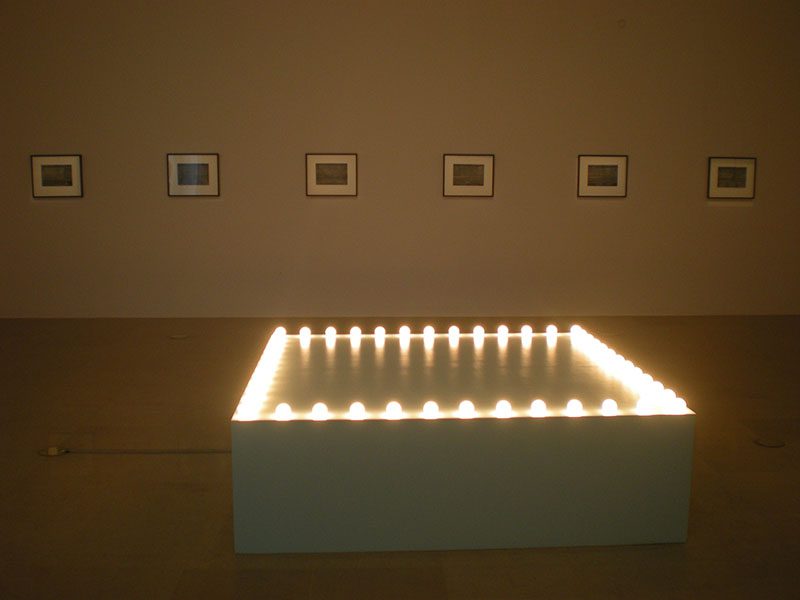

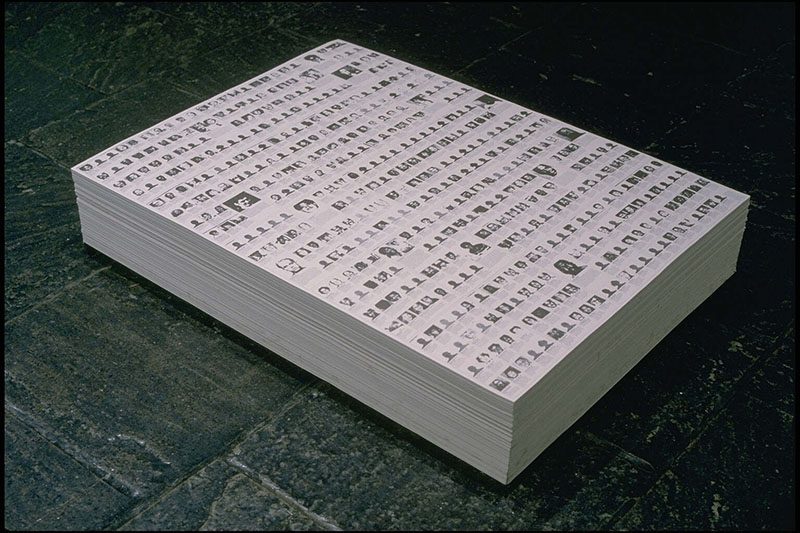

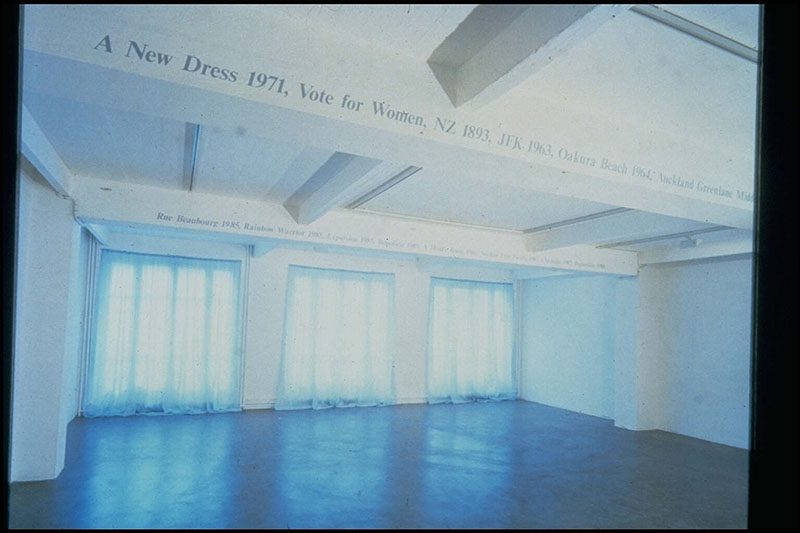

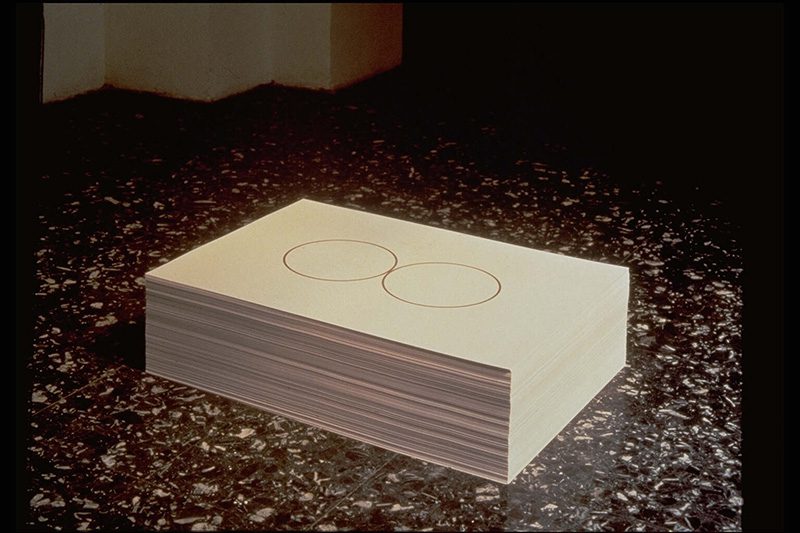

Born in Cuba, the artist moved to New York in 1979 and trained as a photographer, though he would go on to work in a variety of media, including sculpture and installation. In 1989 Gonzalez-Torres began making his stack pieces: blocklike stacks of paper printed with content related to his private life, from which the viewer is invited to take a sheet. Rather than constituting a solid, immovable monument, the stacks can be dispersed, depleted, and renewed over time. And unlike minimalist sculpture, from which their clean geometric forms are derived, they invite the public to interact with them. As the artist stated, “Without the public these works are nothing. I need the public to complete the work. I ask the public to help me, to take responsibility, to become part of my work, to join in”. Relinquishing his work, however, was always a bittersweet undertaking for the artist, as it was tied emotionally to loss of his long-term partner, Ross Laycock, to AIDS in 1991. “I wanted to make an artwork that could disappear”, Gonzalez-Torres related, “That never existed, and it was a metaphor for when Ross was dying. So it was a metaphor that I would abandon this work before it would abandon me”. Around the time of Ross’s death, Gonzalez-Torres made his first lightstring piece (two intertwined lightbulbs on cords dangling from a nail on the wall) as a meditation on lifelong partners and perfect, endless love. In “Untitled (North)” (1993), we see strands of light suspended from the ceiling, some gently resting on the ground, each one representing a human being that at any course of the installation’s duration might be extinguished. While the strands act as reminders of our interconnectedness as humans, the light bulbs also represent the inevitability of death. Hope, however, is never far from Gonzales-Torres’ works, as each light bulb is extinguished it will, eventually, be replaced by another one. His strength as an artist is engaging with themes that deeply affected his personal life, and in so doing, offered the radical notion that these are issues we should all be concerned with, personal issues are at the crux of the relationship between man and society. The artist’s candy spills, piles of candies heaped in a corner from which visitors are welcome to help themselves, are likewise celebrations of generosity and love. Piled usually in the corners of galleries or spread across a gallery floor-again, like minimalist floor installations, the candy sculptures had a designated ideal weight, pieces of candy were intended to be replenished by the exhibitors as the supplies were depleted. Gonzalez-Torres chose evocative weights, specifying that one such sculpture have a weight of 80 kg to represent the ideal weight of the average male while also referring to the weight loss and eventual death of Ross Laycock. His work “Untitled (Perfect Lovers)”, consists of two identical clocks synchronised to mark the same time, but by doing so reiterating the fact that these two clocks will eventually fall out of sync, going in different directions. Even in our most perfect unions, it will be impossible to avoid the simple yet undeniable force of time. All of Gonzalez-Torres’s work shares this enduring hope in the face of loss and impermanence. There is a deep sense of connectedness to others and to the world, as well as an acknowledgment of the faith, trust, and vulnerability that accompany opening ourselves up to something or someone else.

Born in Cuba, the artist moved to New York in 1979 and trained as a photographer, though he would go on to work in a variety of media, including sculpture and installation. In 1989 Gonzalez-Torres began making his stack pieces: blocklike stacks of paper printed with content related to his private life, from which the viewer is invited to take a sheet. Rather than constituting a solid, immovable monument, the stacks can be dispersed, depleted, and renewed over time. And unlike minimalist sculpture, from which their clean geometric forms are derived, they invite the public to interact with them. As the artist stated, “Without the public these works are nothing. I need the public to complete the work. I ask the public to help me, to take responsibility, to become part of my work, to join in”. Relinquishing his work, however, was always a bittersweet undertaking for the artist, as it was tied emotionally to loss of his long-term partner, Ross Laycock, to AIDS in 1991. “I wanted to make an artwork that could disappear”, Gonzalez-Torres related, “That never existed, and it was a metaphor for when Ross was dying. So it was a metaphor that I would abandon this work before it would abandon me”. Around the time of Ross’s death, Gonzalez-Torres made his first lightstring piece (two intertwined lightbulbs on cords dangling from a nail on the wall) as a meditation on lifelong partners and perfect, endless love. In “Untitled (North)” (1993), we see strands of light suspended from the ceiling, some gently resting on the ground, each one representing a human being that at any course of the installation’s duration might be extinguished. While the strands act as reminders of our interconnectedness as humans, the light bulbs also represent the inevitability of death. Hope, however, is never far from Gonzales-Torres’ works, as each light bulb is extinguished it will, eventually, be replaced by another one. His strength as an artist is engaging with themes that deeply affected his personal life, and in so doing, offered the radical notion that these are issues we should all be concerned with, personal issues are at the crux of the relationship between man and society. The artist’s candy spills, piles of candies heaped in a corner from which visitors are welcome to help themselves, are likewise celebrations of generosity and love. Piled usually in the corners of galleries or spread across a gallery floor-again, like minimalist floor installations, the candy sculptures had a designated ideal weight, pieces of candy were intended to be replenished by the exhibitors as the supplies were depleted. Gonzalez-Torres chose evocative weights, specifying that one such sculpture have a weight of 80 kg to represent the ideal weight of the average male while also referring to the weight loss and eventual death of Ross Laycock. His work “Untitled (Perfect Lovers)”, consists of two identical clocks synchronised to mark the same time, but by doing so reiterating the fact that these two clocks will eventually fall out of sync, going in different directions. Even in our most perfect unions, it will be impossible to avoid the simple yet undeniable force of time. All of Gonzalez-Torres’s work shares this enduring hope in the face of loss and impermanence. There is a deep sense of connectedness to others and to the world, as well as an acknowledgment of the faith, trust, and vulnerability that accompany opening ourselves up to something or someone else.