PRESENTATION: Robert Colescott -Art and Race Matters

The career of the American painter Robert Colescott has never been more relevant than at this present moment in time. Given the crisis of race relations, image management, and political manipulation in the current American landscape, his perspectives on race, life, social mores, historical heritage, and cultural hybridity forthrightly confront the state of global culture today.

The career of the American painter Robert Colescott has never been more relevant than at this present moment in time. Given the crisis of race relations, image management, and political manipulation in the current American landscape, his perspectives on race, life, social mores, historical heritage, and cultural hybridity forthrightly confront the state of global culture today.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Chicago Cultural Center Archive

The exhibition “Art and Race Matters The Career of Robert Colescott” brings together over 50 paintings and works on paper spanning 50 years of Robert Colescott’s prolific career. The exhibition invites a renewed examination of the artist, whose work is still as challenging, provocative and relevant now as it was when he burst onto the art scene over five decades ago. Presenting works from across Colescott’s career, the exhibition traces the progression of his stylistic development and the impact of place on his practice, revealing the diversity and range of his oeuvre: from his adaptations of Bay Area Figuration in the 1950s and 60s, to his signature graphic style of the 1970s, and the dense, painterly figuration of his later work. “Art and Race Matters The Career of Robert Colescott” also explores prevalent themes in Colescott’s work, including the complexities of identity, societal standards of beauty, the reality of the American Dream and the role of the artist as arbiter and witness in contemporary life. Soon after graduating from high school in 1943, Colescott enlisted in the army and served in Europe. In 1946, he enrolled in San Francisco State University and then the University of California, Berkeley. In 1949, he went to France on the GI Bill, where he studied in the studio of the French modernist Fernand Léger. When Colescott arrived in Paris, he brought with him a portfolio of works on paper in the abstract style. The modernist pioneer explained to Colescott that he had turned away from his earlier involvement with abstraction because it was not accessible to ordinary people. Colescott decided to adjust to the situation and work from the models and props that Léger had set up in his teaching studio. As he made the transition in his own work, Colescott produced works imitative of Léger’s.

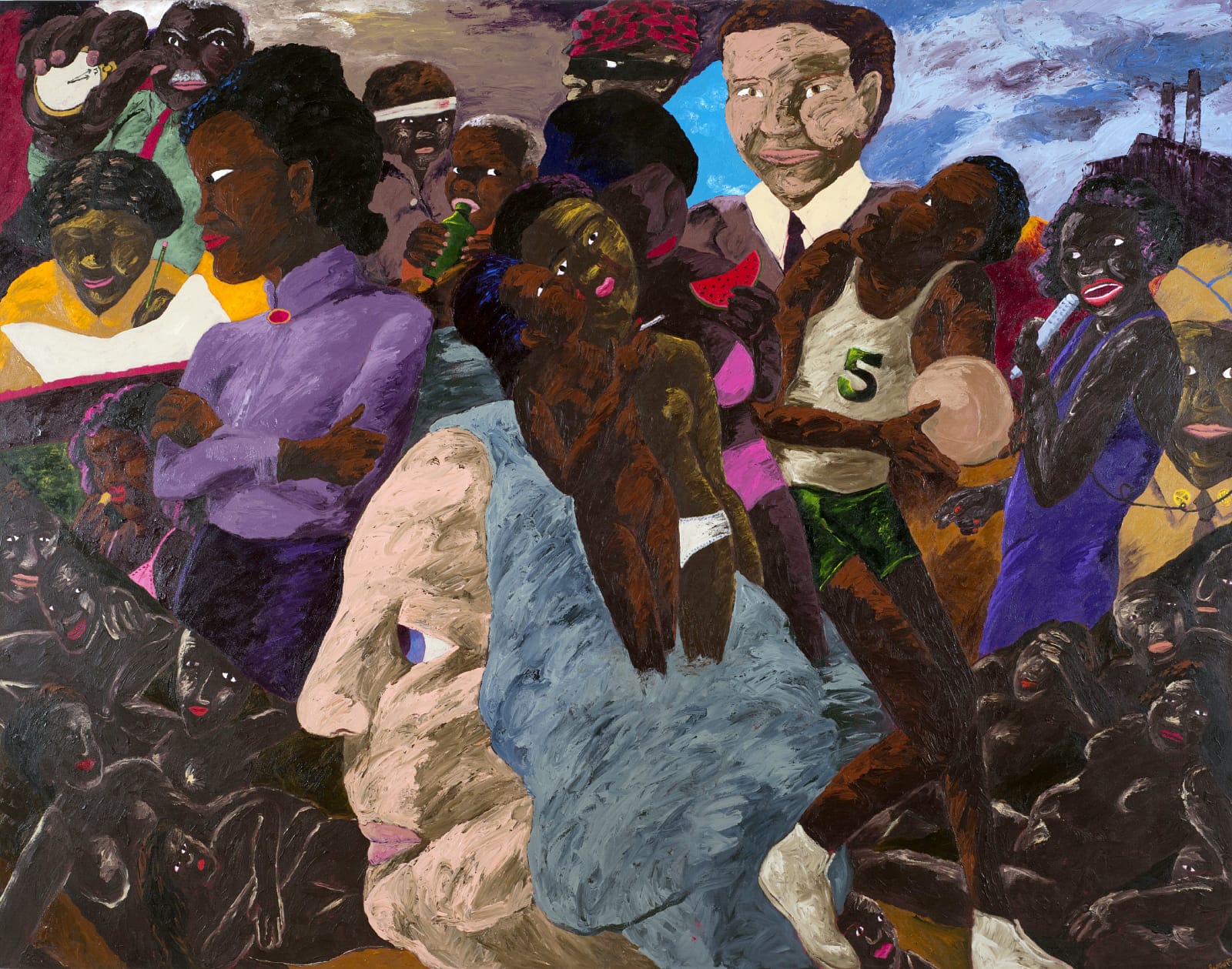

In 1964, Colescott applied for a position at the American Research Center in Cairo, Egypt and became the first artist-in-residence at the Center in the fall of that year. Traveling to Egypt was perhaps the most pivotal turning point in Colescott’s life and career. He was immediately enamored with his new environment, which was very different from the cool, lush Pacific Northwest where he had lived for the past several years. It felt like the change that he had been seeking. Colescott’s “Egyptian” paintings present more abstract representations of the figure in space. On the one hand this could signify a return to earlier stylistic interests, and on the other it might be said that this effect was inspired by the eroded reliefs of the Valley of the Queens, an ancient burial ground south of Cairo. The partly effaced surfaces of these reliefs, with the fragmentary remnants of faces and figures, suggested to Colescott a spirit world or picture of the afterlife, which was, of course, a cornerstone of early Egyptian religion. The figures are sometimes fragmentary or upside down. There is no attempt to describe actual space, as the paintings are built up through large areas of pure color. Colescott returned to the United States in 1969–70, settling in Oakland, California, where he had grown up. His style morphed from the lively zones of color and figuration that marked his Egyptian paintings into a cartoonish style inspired by the comic strips that he enjoyed as a child. In addition, they were also reflective of the countercultural imagery of his West Coast contemporaries, such as Joan Brown, Carlos Villa, Robert Arneson, Roy de Forest, William Wiley, and H.C. Westermann, as well as the Funk cartoonist Robert Crumb. Their work was characterized by an irreverent, no-holds barred approach to making art that reflected a Bay Area sensibility that made it a hotbed of political activism and artistic ferment, having been a key site of the counterculture in the late 1960s and early 70s. Colescott would have his debut on the New York art scene in the 1970s when he showed at the Spectrum and Razor Galleries. His fresh approach to figuration led to his being included in the groundbreaking exhibition “Not for Laughs Only” curated by Marcia Tucker at the New Museum in 1981. His initial strategy was to revisit the work of prominent artists in history such as Vincent van Gogh, Eugène Delacroix, Emanuel Leutze, and Pablo Picasso, and selectively render figures in the original compositions as Black people. This allowed him to address subject matter that was largely ignored by art history, while introducing a larger universe for aesthetic and artistic discourse.

By the mid-1970s, Colescott was fully engaged in his appropriation of art history. “Eat Dem Taters” a spoof of van Gogh’s “Potato Eaters: is particularly notorious. Here Colescott replaces van Gogh’s somber peasants with exuberantly grinning minstrel figures in order to send up the myth of the “happy darky.” The notion that Black people could be happy with very little was a staple of pre-World War II Hollywood films. This concept was also included in school textbooks of the period, in which Black people were described as fortunate to be enslaved, since slavery removed them from their previous, barbaric circumstances in Africa. Colescott effectively uses the stylization of racist stereotypes of Black people to draw viewers into the painting; and, regardless of their reaction, he forced them to confront their racist attitudes, anger or compliance. In “Les Demoiselles d’Alabama: Vestidas” (1985), is one of two appropriations of Pablo Picasso’s 1907 “Demoiselles d’Avignon” in the Museum of Modern Art that Colescott painted in 1985. He designated the two versions “desnuda” (nude) and “vestida” (clothed) referring as well to Francisco Goya’s two representations of a “maja” (lower-class woman). The “Les Demoiselles d’Alabama” are rendered in Colescott’s characteristic fleshy, gestural style, which contrasts with Picasso’s more linear, graphic style. This version shows the figures dressed in exuberant clothing and styles. He explained that these appropriations were “about sources and ends,” as Picasso “started with European art and abstracted through African art, producing ‘Africanism but keeping one foot in European art.

As in his reconstructions of masterpieces of Western art history, Colescott enjoyed debunking the narrative twists and turns of the “official” versions of biblical stories, as seen in his version of the story of the Garden of Eden in “A Legend Dimly Told” (whose title revisits a 1961 painting also in this exhibition) or “Susanna and the Elders (Novelty Hotel)”, and in his ahistorical encounters between Aunt Jemima and Colonel Sanders. Aunt Jemima, in particular, seems to have captured his imagination. In two additional story lines, she becomes the consort of a Western gold rusher, Cactus Jack, or the impressive avatar of Willem de Kooning’s awesome image, “Woman I”. As Colescott noted in 1989, “I think the way I have appropriated painting is subversive because my version of the “Déjeuner sur l’herbe” or the de Kooning woman puts into question the ownership of the idea. The fact that the original work can be redone questions its value.” He also noted that if he created “something that really sticks in people’s minds” when they see the original version, “they’re going to think of mine.” The most notable apparition of Aunt Jemima is in Colescott’s 1978 appropriation of Willem de Kooning’s “Woman I” of 1952-53 (Museum of Modern Art), one of the icons of Abstract Expressionism. “I Gets a Thrill, Too, When I Sees De Koo” replaces the grimacing figure in the de Kooning with a mischievous grinning avatar of Aunt Jemima. But this painting is also a variation of a Pop Art riff: “I Gets a Thrill When I See Bill” by Mel Ramos, where the head of the woman in the de Kooning is replaced with the headshot of a contemporary 1970s model. Colescott navigates a path from the gestural distortion of the de Kooning, through the glamorized version by Ramos. Thus, his Aunt Jemima acquires the sexual gloss of the Ramos, even as Colescott circles back technically to the gestural figuration of the de Kooning and the 1950s and 60s figural trends from which he has developed his style.

Since the 1980s, the issue of identity has preoccupied our increasingly globalized society. In Colescott’s career, that sense of identity was explored in various ways, including how he saw himself as a rogue romantic figure and an artist. Colescott was an astute and diligent student of cultural history and employed metaphor and allusion to deal with a variety of current events he experienced throughout his life. He deftly dealt with the ironic situation of the Black soldier, the dichotomy between domestic policy and foreign relations; interracial relationships were considered along with political assassinations, the struggles in the Middle East, and the US/ Mexico border. His New Orleans, Creole roots also drew him to the complexities of interracial identity, and his inherently bourgeois upbringing forced him to deal with the risks of assimilation—alienation from community, the possible loss of positive self-imagery and the endurance of trite stereotyping as the exotic “other.” Colescott embarked on a series of paintings in the 1980s whose titles played on the platitude “those who ignore the past are doomed to repeat it;” but, the titles provide a slight switch in nuance: “Knowledge of the Past Is the Key to the Future”. In this exhibition, works from this series examine the overlooked role of the African American Matthew Henson, who actually led the way to the North Pole as part of Admiral Peary’s expedition team, the legacy of miscegenation and unacknowledged ancestry and the social and economic challenges of the disenfranchised . In these paintings, Colescott not only captures the kernel of the event, he surrounds it with “subtexts, pretexts, post-texts and narratives-within narratives” as how critic Henry Louis Gates, Jr. once described the work of writer Ishmael Reed. In the early 2000s, Colescott had to face the effects of Parkinson’s syndrome. Despite the physical challenges he faced, Colescott continued to paint, as his figurative style evolved into richly modulated compositions that became increasingly abstract. Works such as “Alas, Jandava” present a more esoteric narrative in a child-like scribbly style. In”Pick a Ninny Rose and Sleeping Beauty?”, form, gesture, fully saturated color, and blank space come together in works that are dream-like and nightmarish at the same time. It would seem that Colescott allowed his subconscious to roam freely in an unresolved way, which relates morphologically and compositionally to the character of his paintings in the first few years of the twenty-first century.

Photo: Robert Colescott , Sleeping Beauty?, 2002, Acrylic on canvas, 85¼ x 145⅛ inches. © 2019 Estate of Robert Colescott / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the Estate and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles / New York / Tokyo. Photo credit: Joshua White. L2019.104.2

Info: Curators: Lowery Stokes Sims and Matthew Weseley, Chicago Cultural Center, 78 E. Washington St., Chicago, IL, USA, Duration: 4/12/2021-29/5/2022, Days & Hours: Daily 10:00-17:00

Right: Robert Colescott , Nubian Queen, 1966, Acrylic on canvas, 78 x 59 inches. © 2019 Estate of Robert Colescott / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Private Collection; New York City, NY. Photo credit: Adam Reich. L2019.104.47