ART-PRESENTATION: Global Groove Art, Dance, Performance and Protest

The major interdisciplinary exhibition to dance and its links to the fine arts, fashion design and performance art, “Global Groove. Art, Dance, Performance and Protest” looks back across 120 years of dance and art history, and beyond Europe and North America to Asia. The focus is on those trailblazing moments when artists from Western and (South) East Asian societies meet and new forms of artistic expression arise.

The major interdisciplinary exhibition to dance and its links to the fine arts, fashion design and performance art, “Global Groove. Art, Dance, Performance and Protest” looks back across 120 years of dance and art history, and beyond Europe and North America to Asia. The focus is on those trailblazing moments when artists from Western and (South) East Asian societies meet and new forms of artistic expression arise.

By Dimitris Lempesis

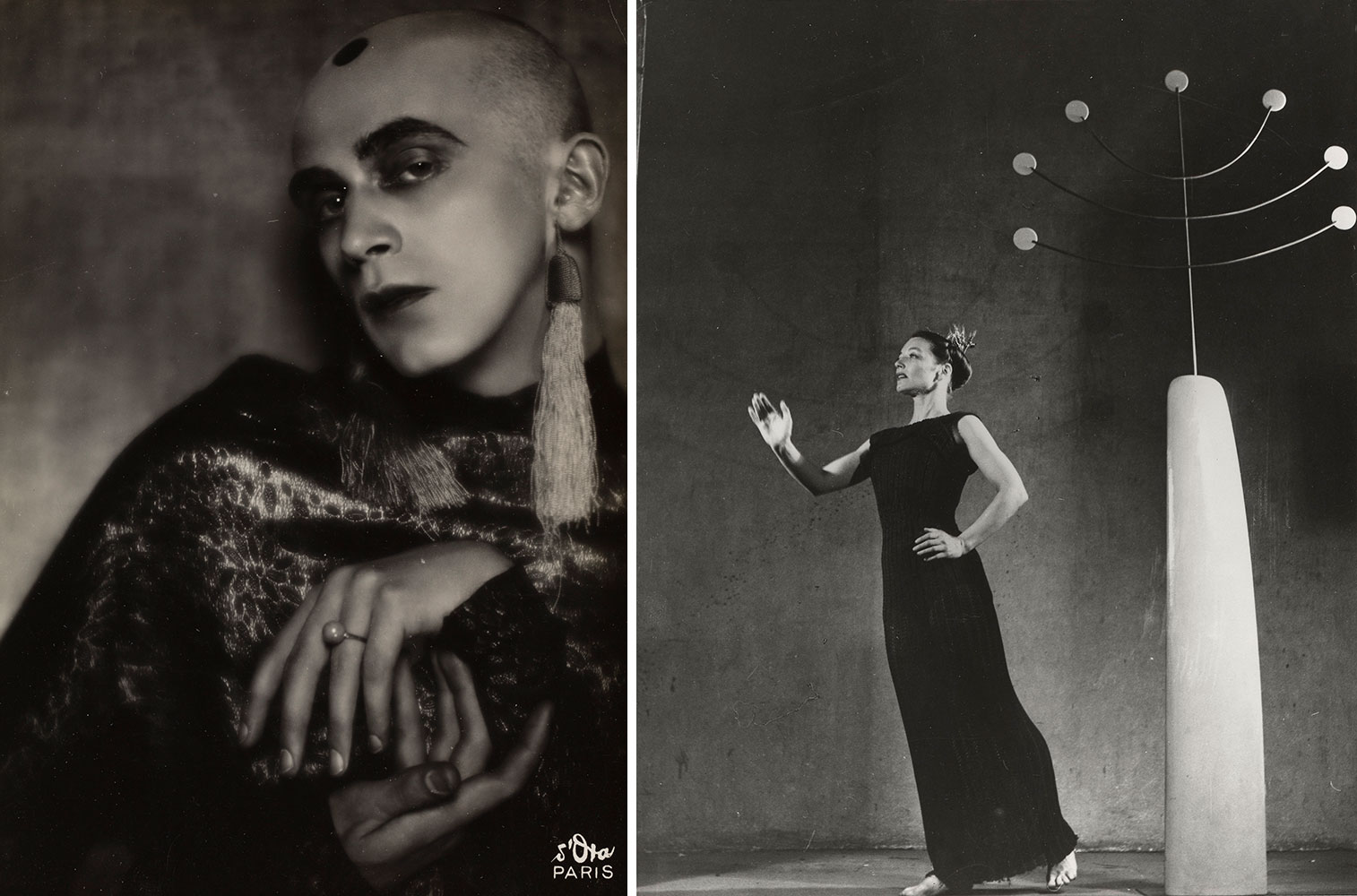

Photo: Museum Folkwang Archive

From the early performances by Asian dancers in Europe around 1900 to the pioneers of modern dance, and on to the first Happenings by Japanese Butoh dancers, the exhibition “Global Groove. Art, Dance, Performance and Protest” explores a West-East cultural history of contact—right up to contemporary collaborations. The linkages between the Western and Eastern avant-gardes are portrayed using the history of contact between choreographers, dancers, artists and intellectuals from Europe, the United States, and Asia. A prologue and six chapters highlight the power of dance to stimulate social developments. On show are over 300 exhibits by more than 80 different artists, amongst them John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham, Leiko Ikemura, Rei Kawakubo, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, William Klein, Harald Kreutzberg, Isamu Noguchi, Kazuo Ohno, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, Auguste Rodin, Ulrike Rosenbach, Sonia Khurana, and Mary Wigman. Paintings, sculptures, costumes, photographs, video works, extensive installations and performances guide visitors away from metropolises in the West, such as Paris and New York, and out into rural southern England and then beyond, to Cambodia and India, and even to the north of Japan. Two works form an associative space and prompt reflection on movement and transformation. In her renowned “dance of light” Loïe Fuller (1862– 1928) presented an abstracted body and its shape, in the unfurling of organic-amorphous veils on stage, and in so doing set new standards with her dance and media aesthetic. In her expansive “Foreverago tapestry” Pae White offers an astonishing combination of ornamental, organic, and technical elements. With their “aesthetics of the infinite”, both artists take us to the very limits of vision.

The chapter “Foreign Dance” focuses on early encounters between Western and (South) East Asian dance avantgardes. Individual celebrities such as poet Rabindranath Tagore, dancer Raden Mas Jodjana or art collectors Karl Ernst Osthaus and Rolf de Maré were amongst the first to expand their radius through travel, and at the beginning of the 20th century they started questioning Eurocentric approaches. The Western pioneers found inspiration and material for their thoughts in art history museums and in the non-European cultures that arrived in Europe and North America thanks to the World and Colonial Exhibitions. Parallel to this, the first Asian ensembles confidently performed on Western stages. A hundred years later, in his installation entitled “At Twilight” Simon Starling addresses the enthusiasm among W. B. Yeats’ circle for Japanese culture and for dancer Michio Ito. Japan’s Gutai group symbolized artistic upheaval in the country. It was no coincidence that it started in the period of liberalization that began after the US occupation of Japan came to an end. In swift succession, from 1954 onwards trailblazing works arose that attributed a central role to the human body. Gutai member Kazuo Shiraga started as early as 1952 painting his canvases using his feet, both referencing traditional Japanese art and engaging with the paintings of Jackson Pollock, who related the body directly to the canvas. Pollock’s technique of dripping suddenly became known the world over in 1949 on the back of an article in Life magazine. From 1955 onwards the group brought out its own Gutai magazine, presenting images of its actions and performances – and the members also always sent a copy to Pollock in New York.

In 1959, Tatsumi Hijikata) staged the very first Butoh performance with the homoerotic duo Kinjiki (Forbidden Colors). The dancers were Kazuo Ohno and his son Yoshito with their faces blackened by oil, and they were accompanied by soft blues notes. The blackfacing was followed in Anma (The Masseurs) by the white facial and body powder that became the hallmark of Butoh dance. While Japan was fast emerging as the leading technology nation worldwide and Tokyo was preparing to host the 1964 Olympic Games, there was a pronounced rebellious rollback movement in young art that was critical of consumerism, something that led to an increase in performative art practices: abattoirs, streets, backyards and open fields all became stages for physical action and expression. In Hijikata’s “Asbestos Studio” half-commune, half-avantgarde salon, a loosely composed group of young people shared their lives, work, and art. Alongside John Cage, Hijikata was one of the most important minds stimulating a transgressive concept of art. Archaic, physical and ritual-like, Butoh dance put its finger firmly on a nerve in the climate of post-War Japan. Ever since the Second World War, the history of the USA has been closely bound up with that of Japan. Thus, from the 1950s onwards, there was also increased interaction between artists from both countries. In the West, John Cage was representative of an entire generation that was influenced by Zen Buddhism and its understanding of void and reduction. For their part, the Japanese artists responded to the Abstract Expressionism of Jackson Pollock, for example, and decisively shaped the Fluxus movement. Thanks to mobility between continents becoming ever easier, there was brisk movement between the two countries. New cultural stimuli resulted from the encounters between for example Merce Cunningham and Rei Kawakubo, Martha Graham and Isamu Noguchi, or Pina Bausch and Yohji Yamamoto.

The year 1970 saw the collaboration between the non-profit organization E.A.T. founded amongst others by Billy Klüver and Robert Rauschenberg and the Indian feminist and choreographer Chandralekha. In New York a film was made with Andy Warhol, in which Chandralekha demonstrates a series of symbolic hand gestures. Photographers Harry Shunk and Janos Kender were present during filming, and a series of photos was produced showing Chandralekha performing the hand gestures the so-called “Hasta Mudras”. In the early 1970s, the second generation of Butoh dancers impressively gave this dance form international reach. Artist duo Eiko Otake and Takashi Koma Otake left Japan in 1972 for Europe and the US. Along with them they took three books: a book on Noh theatre; Vincent van Gogh’s letters to his brother Theo; and the diary of Russian dancer Vaslav Nijinsky. In Hanover, Mary Wigman introduced the couple to actors in the German dance scene. Setting themselves off from the Dance of Darkness of the Butoh founders, they called their early performances “White Dance” (1972-74). With their Poor Art Style, the duo championed a narrative thrust that through the subjective, pain and protest fostered a sense of historical reality. French dancer and choreographer Boris Charmatz calls his homage to Japanese expressive dance Rebutoh. He shares with Butoh inventor Tatsumi Hijikata the idea of the human body as an archive of (hi)stories. In Rennes in France, Charmatz founded the Musée de la Danse, where he collects movements and gestures. His new terrain initiative is a dance house without roofs or walls: Human bodies form a mobile structure on a green base. Each piece breaks a taboo or explodes a shape. Inspired by the karstic grounds of the Haniel slag heap in Bottrop, the film loop Levée shifts between dance and documentary film. It throws dance into a no man’s land be-tween battle arena, disaster zone, and sci-fi. The dancers are devoured by a huge vortex like refugees. The choreography is based on 25 gestures. Repetition and spiral-like movements engender an endless alphabet of dance.

Artists: Charles Atlas, Pina Bausch, Alice Boner, James Byrne, John Cage, Chandralekha, Boris Charmatz & César Vayssié, Padmini Chettur, Merce Cunningham, Ruth St. Denis, Eiko & Koma, Siegfried Enkelmann, Hans Evert, Loïe Fuller, John Godfrey, Martha Graham, Marion Gray, Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, George Groslier, Atelier Frans Hals, Philippe Halsman, Madame Hanako, Bernd Hartung, Minoru Hirata, Tatsumi Hijikata, Claire Holt, Eikoh Hosoe, Leiko Ikemura, Mette Ingvartsen, Raden Mas Jodjana, Kurt Jooss, Dora Kallmus (Madame d’Ora), Rei Kawakubo, Edmund Kesting, Sonia Khurana, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, William Klein, Harald Kreutzberg, Anouk Kruithof, Shigeko Kubota, Brüder Lumière, Victor Magito, Albert & David Maysles, Margaret Mead & Gregory Bateson, Peter Moore, Bimol Mukherjee, Kelly Nipper, Isamu Noguchi, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, Irving Penn, Ad Petersen, Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Timm Rautert, Albert Renger-Patzsch, Atelier Robertson Auguste Rodin, Ulrike Rosenbach Charlotte Rudolph, Thomas Ruff, Otto Sarony, Sasha (Alexander Stewart) Tejal Shah, Uday Shankar, Kazuo Shiraga, Harry Shunk & Janos Kender, Julius Hans Spiegel, Simon Starling, Edward J. Steichen, White Studio, Shomei Tomatsu, Umbo, François Antoine Vizzavona, Walter Vogel, Pae White, Mary Wigman, Yohji Yamamoto, Sada Yacco, Haegue Yang and Zygmunt Szajer.

Photo: Mette Ingvartsen, The Life Work, 2021, Voices and performance Taeko Gericke, Yoko Iso, Michiko Meid, Kumiko Watanabe, Installation with soundtrack 65 min, Tree, lenses, stones, light, dimensions variable, A produktion by Mette Ingvartsen / Great Investment, Co-produced on behalf of Ruhrtriennale, In Cooperation with the Museum Folkwang, Essen, © Mette Ingvartsen, Photo: Katja Illner

Info: Curators: Anna Fricke, Marietta Piekenbrock, Brygida Ochaim and Christin, Museum Folkwang, Museumsplatz 1, Essen, Germany, Duration: 13/8-14/11/2021, days & Hours: Tue-Wed & Sat-Sun 10:00-18:00, Thu-Fri 10:00-20:00, www.museum-folkwang.de

Right: Auguste Rodin, Dancer from Royal Cambodian Ballet, 1906, Pencil and watercolour on paper, 30.7 x 19.5 cm, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Photo: Erik Cornelius / Nationalmuseum

![Boris Charmatz/César Vayssié, Levée, 2014, Video, colour, mute, 14:22 Min., Recording : Ruhrtriennale, 23.8.2021, Distribution: [terrain], © Musée de la danse / Same Art – 2014, Photo credit: © César Vayssié](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/MFolkwang_Global_Groove_Boris_Charmatz_César_Vayssié_Levée_2014_300.jpg)

Right: Isamu Noguchi, Set Element (Pillar with Pink Leaves) for Martha Graham’s Dark Meadow, 1926, B/W-Photography, 20.3 x 25.4 cm, The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York, © The Noguchi Museum / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021