PHOTO:Masculinities-Liberation through Photography

The group exhibition “Masculinities: Liberation through Photography” explores the diverse ways in which masculinity is experienced, performed and socially constructed through photography and film from the 1960s to the present day. The exhibition is part of EMOP Berlin – European Month of Photography 2020 and builds on the Gropius Bau’s history as a platform for staging exhibitions by important 20th century and contemporary photographers

The group exhibition “Masculinities: Liberation through Photography” explores the diverse ways in which masculinity is experienced, performed and socially constructed through photography and film from the 1960s to the present day. The exhibition is part of EMOP Berlin – European Month of Photography 2020 and builds on the Gropius Bau’s history as a platform for staging exhibitions by important 20th century and contemporary photographers

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Gropius Bau Archive

At a time when ideas around masculinity are undergoing a global crisis and concepts such as “toxic” and “fragile” masculinity are shaping social discourse, the exhibition “Masculinities: Liberation through Photography” presents over 300 works by 50 international artists. Touching on themes of patriarchy, power, queer identity, race, class, sexuality and hyper-masculine stereotypes, as well as female perceptions of men, the works present masculinity as an unfixed, performative identity. Presented across six sections, the exhibition “Masculinities: Liberation through Photography,” grapples with masculinity in its expansive forms. The first chapter, “Disrupting the Archetype”, explores the representation of conventional and at times clichéd masculine subjects such as soldiers, cowboys, athletes, bullfighters, body builders and wrestlers. By reconfiguring the representation of traditional masculinity – loosely defined as an idealised, dominant heterosexual masculinity – the artists presented here challenge our ideas of these hypermasculine stereotypes. The second chapter, “Male Order – Power, Patriarchy and Space” invites the viewer to reflect on the construction of male power, gender and class. The artists gathered here have all variously attempted to expose and subvert how certain types of masculine behaviour have created inequalities both between and within genders. In contrast to the conventions of the traditional family portrait, the artists gathered in the third chapter, “Too close to Home: Family and Fatherhood”, set out to record the “messiness” of life, reflecting on misogyny, violence, sexuality, mortality, intimacy and unfolding family dramas, presenting a more complex and not always comfortable vision of fatherhood and masculinity. In defiance of the prejudice and legal constraints against homosexuality over the last century in Europe, the United States and beyond, the works presented in the forth chapter, “Queering Masculinity”, highlight how artists from the 1960s onwards have forged a new politically-charged queer aesthetic. The fifth chapter, “Reclaiming the Black Body” foregrounds artists who have, over the last five decades, consciously subverted expectations of race, gender and the white gaze by reclaiming the power to fashion their own identities. As the second-wave feminist movement gained momentum through the 1960s and 1970s, female activists sought to expose and critique entrenched ideas about masculinity and to articulate alternative perspectives on gender and representation. Against this background, the artists introduced in chapter six “Women on Men: Reversing the Male Gaze” have made men their subject with the intention of subverting power structures.

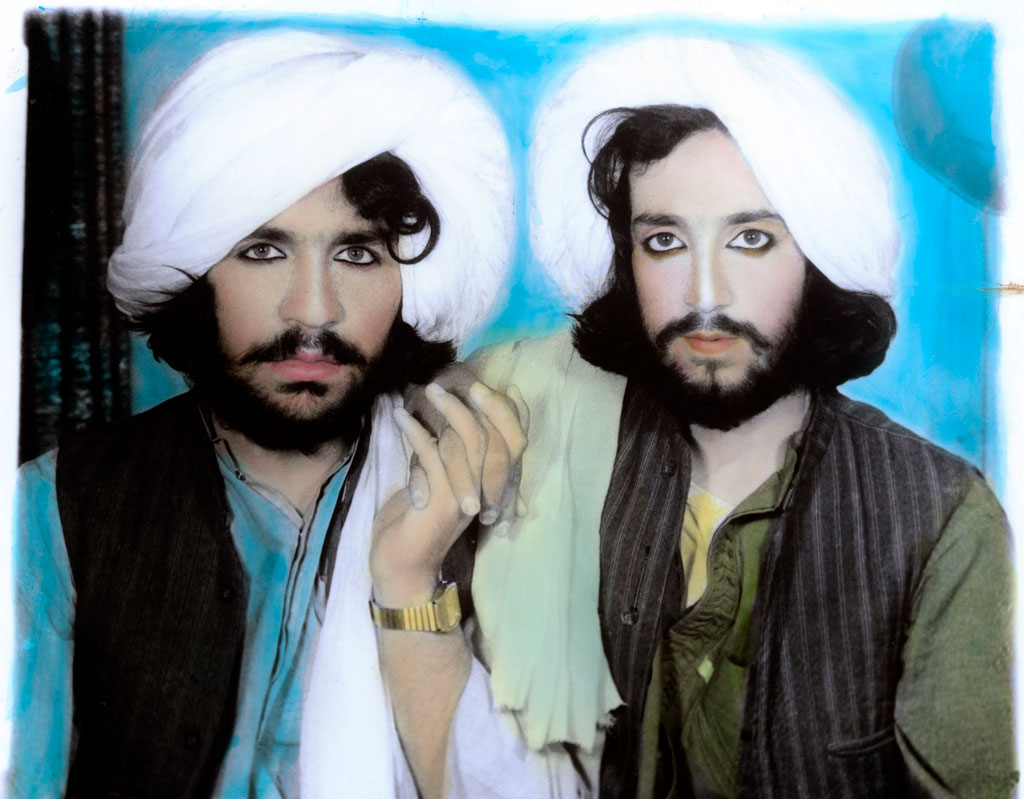

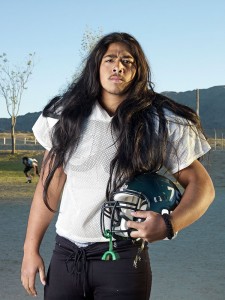

Seeking to disrupt and destabilise the myths surrounding modern masculinity, highlights include the work of artists who have consistently challenged stereotypical representations of masculinity, including Collier Schorr, Adi Nes, Akram Zaatari and Sam Contis, whose series “Deep Springs” (2018) draws on the mythology of the American West and the rugged cowboy. Contis spent four years immersed in an all-male liberal arts college north of Death Valley meditating on the intimacy and violence that coexists in male-only spaces. Complicating the conventional image of the fighter, Thomas Dworzak’s acclaimed series “Taliban” consists of portraits found in photographic studios in Kandahar following the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, these vibrant portraits depict Taliban fighters posing hand in hand in front of painted backdrops, using guns and flowers as props with kohl carefully applied to their eyes. Trans masculine artist Cassils’ series “Time Lapse” (2011), documents the radical transformation of their body through the use of steroids and a rigorous training programme reflecting on ideas of masculinity without men. Elsewhere, artists Jeremy Deller, Robert Mapplethorpe and Rineke Dijkstra dismantle preconceptions of subjects such as the wrestler, the bodybuilder and the athlete and offer an alternative view of these hyper-masculinised stereotypes. The exhibition examines patriarchy and the unequal power relations between gender, class and race. Karen Knorr’s series “Gentlemen” (1981-83), comprised of 26 black and white photographs taken inside men-only private members’ clubs in central London and accompanied by texts drawn from snatched conversations, parliamentary records and contemporary news reports, invites viewers to reflect on notions of class, race and the exclusion of women from spaces of power during Margaret Thatcher’s premiership. Toxic masculinity is further explored in Andrew Moisey’s 2018 photobook “The American Fraternity: An Illustrated Ritual Manual” which weaves together archival photographs of former US Presidents and Supreme Court Justices who all belonged to the fraternity system, alongside images depicting the initiation ceremonies and parties that characterise these male-only organisations. With the rise of the Gay Liberation Movement through the 1960s followed by the AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s, the exhibition showcases artists such as Peter Hujar and David Wojnarowiz, who increasingly began to disrupt traditional representations of gender and sexuality. Hal Fischer’s critical photo-text series “Gay Semiotics” (1977) classified styles and types of gay men in San Francisco and Sunil Gupta’s street photographs captured the performance of gay public life as played out on New York’s Christopher Street, the site of the 1969 Stonewall Uprising. Other artists exploring the performative aspects of queer identity include Catherine Opie’s seminal series “Being and Having” (1991) showing her close friends in the West Coast’s LGBTQ+ community sporting false moustaches, tattoos and other stereotypical masculine accessories. Elle Pérez’s luminous and tender photographs explore the representation of gender non-conformity and vulnerability, whilst Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s fragmented portraits explore the studio as a site of homoerotic desire. During the 1970s women artists from the second wave feminist movement objectified male sexuality in a bid to subvert and expose the invasive and uncomfortable nature of the male gaze. In the exhibition, Laurie Anderson’s seminal work “Fully Automated Nikon (Object/Objection/Objectivity)” (1973) documents the men who cat-called her as she walked through New York’s Lower East Side while Annette Messager’s series “The Approaches” (1972) covertly captures men’s trousered crotches with a long-lens camera. German artist Marianne Wex’s encyclopaedic project “Let’s Take Back Our Space: ‘Female’ and ‘Male’ Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures” (1977) presents a detailed analysis of male and female body language and Australian indigenous artist Tracey Moffatt’s awkwardly humorous film “Heaven” (1997) portrays male surfers changing in and out of their wet suits. Further highlights include New York based artist Hank Willis Thomas, whose photographic practice examines the complexities of the black male experience; celebrated Japanese photographer Masahisa Fukase’s “The Family” (1971-89), chronicles the life and death of his family with a particular emphasis on his father; and Kenneth Anger’s technicolour experimental underground film “Kustom Kar Kommandos” (1965) explores the fetishist role of hot rod cars amongst young American men.

Participating Artists: Bas Jan Ader, Laurie Anderson, Kenneth Anger, Liz Johnson Artur, Knut Åsdam, Richard Avedon, Aneta Bartos, Richard Billingham, Cassils, Sam Contis, John Coplans, Jeremy Deller, Rineke Dijkstra, George Dureau, Thomas Dworzak, Hans Eijkelboom, Fouad Elkoury, Hal Fischer, Samuel Fosso, Anna Fox, Masahisa Fukase, Sunil Gupta, Kiluanji Kia Henda, Peter Hujar, Isaac Julien, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Karen Knorr, Deana Lawson, Hilary Lloyd, Robert Mapplethorpe, Peter Marlow, Ana Mendieta, Annette Messager, Duane Michals, Tracey Moffatt, Andrew Moisey, Richard Mosse, Adi Nes, Catherine Opie, Elle Pérez, Herb Ritts, Kalen Na’il Roach, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Collier Schorr, Clare Strand, Mikhael Subotzky, Larry Sultan, Wolfgang Tillmans, Hank Willis Thomas, Piotr Uklański, Andy Warhol, Karlheinz Weinberger, Marianne Wex, David Wojnarowicz and Akram Zaatari.

Info: Curator Alona Pardo, Gropius Bau, Niederkirchnerstraße 7, Berlin, Duration: 16/10/20-10/1/21, Days & Hours: Mon & Wed-Sun 10:00-19:00, thu 10:00-21:00, www.berlinerfestspiele.de