ART-PRESENTATION: Bruce Nauman

For more than 50 years Bruce Nauman has continually tested and reinvented what an artwork can be. His work is difficult to confine to any one movement, genre or medium. However his highly experimental approach makes him a key figure within art today. His interest in ambiguity and shades of meaning relates to daily human experience, where certainty is not always guaranteed.

For more than 50 years Bruce Nauman has continually tested and reinvented what an artwork can be. His work is difficult to confine to any one movement, genre or medium. However his highly experimental approach makes him a key figure within art today. His interest in ambiguity and shades of meaning relates to daily human experience, where certainty is not always guaranteed.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Tate Archive

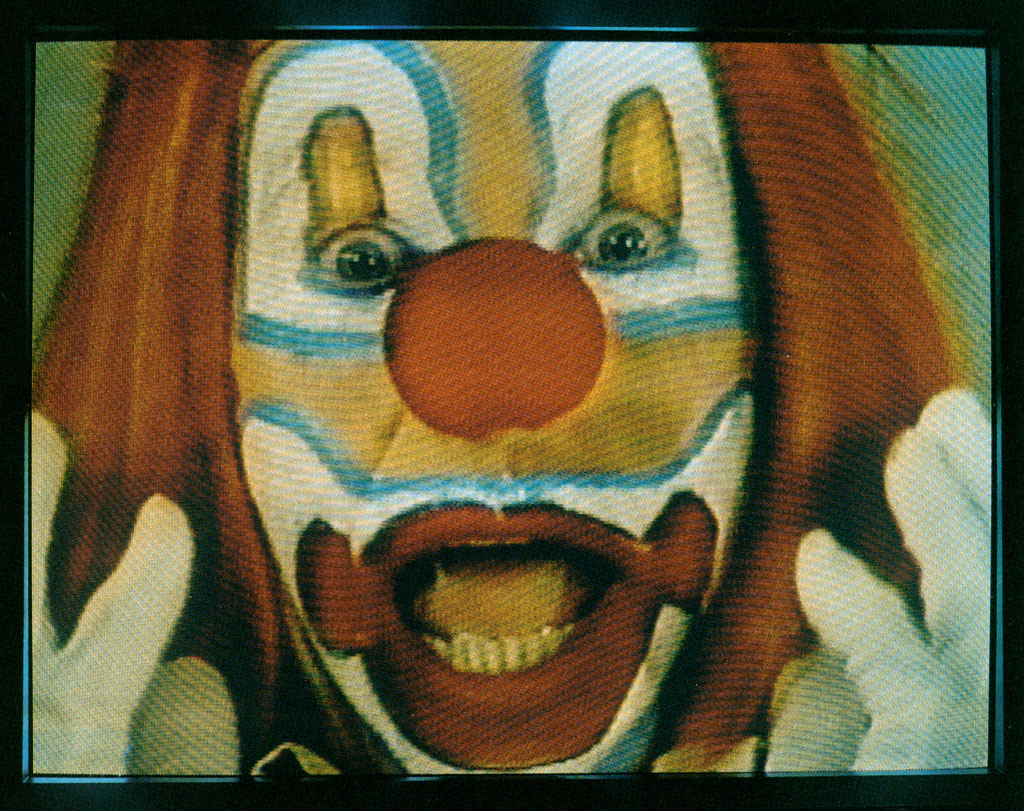

The exhibition at Tate Modern is a survey of Bruce Nauman’s work but is not displayed chronologically. It explores how he has been preoccupied by themes such as the artist’s studio, the body, language, and control. His work is full of ideas, and is often described as conceptual, but he also enjoys playing with material and making objects in the studio. Throughout his long career, Nauman has refused to assign specific meanings to his artworks. He thereby encourages viewers to bring their own experiences to the work, and to create alternative readings. Sixteen years after it was commissioned for Tate Modem’s Turbine Hall, Bruce Nauman’s “Raw Materials” is once again installed at the museum. Consisting of a collage of spoken text recorded by Nauman over 40 years, this pioneering work has been specially reconfigured for the public stairwell. Inspired by his background in music, sound has always been central to Nauman’s practice and the voice is often an important component within many of his works. “Raw Materials” brings together 22 recordings of text from works across Nauman’s career, producing what could be considered an aural retrospective of the artist’s work to date. This includes the powerful “Anthro/Socio (Rinde Spinning)” (1992) which can be viewed in full inside the exhibition. The title “Raw Material” was first coined for videos made by Nauman in the early 90s – when videographer Dennis Diamond asked how to title the raw material they had recorded together, Nauman replied “Raw Material – that sounds good”. “MAPPING THE STUDIO II with color shift, flip, flop & flip/flop (Fat Chance John Cage)” (2001) exemplifies Nauman’s curiosity about the usually overlooked aspects of the world surrounding him. Seven large video projections present different views within Nauman’s studio, in New Mexico, US. They were all filmed at night over a period of several weeks. The subject matter is particularly mundane. As a consequence, whenever a mouse, moth or cat enters the frame, it becomes an event. Nauman has described how, while viewing the individual channels of this work, it is difficult to focus on any one part of an image. ‘You have to kind of not watch anything, so you can be aware of everything’, he advised. As the title suggests, the images are sometimes digitally ‘flipped’ or ‘flopped’ – turned back to front or upside down. Their colour gradually shifts as the sun rises, heightening the awareness of time passing. The title also refers to experimental composer John Cage. From his earliest works in “Clown Torture” (1987) Nauman has frequently explored the response of the body to physical and psychological pressure. Here, in contrast to the clowns found in children’s entertainment, he explores the menacing side of this archetype. The clown is played by an actor. Nauman has said, “when you think of a vaudeville clown, there is a lot of cruelty and meanness … Then there’s the history of the unhappy clown”. The clown’s obligation to perform, and to obscure their ‘true’ self, interested Nauman. As the work is playing continuously in the gallery, viewers can encounter the videos at any given moment. Nauman takes advantage of circular tales that can be understood at any point in the repetitive sequence: “Pete and Repeat were sitting on a fence: Pete fell off. Who was left? Repeat: Pete and Repeat were sitting on a fence…”

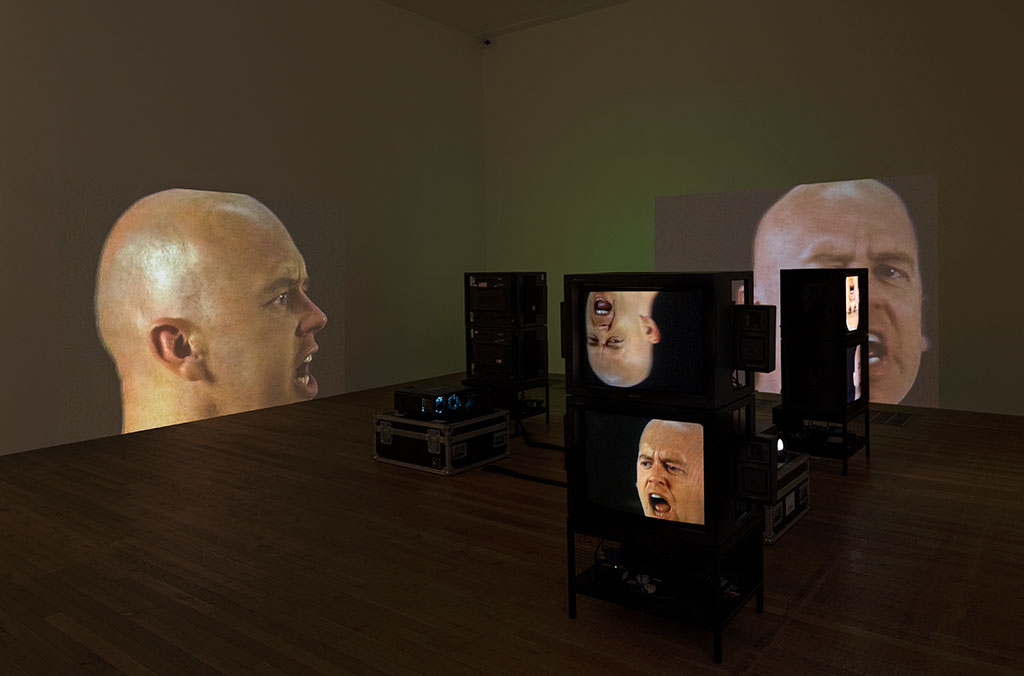

“Double Steel Cage Piece” (1974) consists of two cages, one contained inside the other. The work’s modular appearance resonates with minimalist art made in the US during the 1970s. As with other works Nauman made at this time, its dimensions correspond to the size of his own body. There is a narrow gap between the two cages, barely sufficient for anyone to squeeze through. Nauman recognised that moving sideways along this gap could provoke feelings of anxiety and entrapment. His use of steel mesh, evocative of prison yards, increases this feeling of confinement and surveillance. Nauman intended that the doorway of the cage should be left open, offering viewers the possibility of entering the work. Today at Tate Modern, visitors are not allowed to enter but footage of the experience can be seen on the adjacent screen. In “Anthro / Socio (Rinde Spinning)” (1992), projected on three sides of the room is the rotating, disembodied head of a man. It shouts ‘Feed Me, Eat Me, Anthropology’, ‘Help Me, Hurt Me, Sociology’ and ‘Feed Me, Help Me, Eat Me, Hurt Me’. Aggressive and unsettling, Nauman’s performer screams for fulfilment of the most base human instincts. Before creating this work, Nauman had been experimenting with making sculptures of heads cast in wax. Anthro/Socio is a translation of this interest into video. He has retained some sculptural elements with the projectors sitting on cardboard boxes, surrounded by stacked monitors. The performer in this work is classically trained actor and singer Rinde Eckert. Eckert’s skills as a performer are evident. He maintains a consistent, stern expression as he is shouting, making it seem as though his voice is detached from his body. The meaning of the work “Black Marble Under Yellow Light” (1981-88) remains ambiguous, emphasised by the descriptive factual title. This is in contrast to the poetic titles favoured by Nauman for other floor-based, sculptural installations from the late 1970s, which were often accompanied by passages of printed text. The marble blocks are in two slightly different sizes ‘because I thought it disturbed the space in a horizontal way’. Fluorescent lighting is a feature Nauman used in his corridor installations of the early 1970s. Here, the insistent yellow light is chosen for its unsettling qualities, associated with the sodium lights of underpasses and railway goods yards. The neon “Hanged Man” (1985) is based on the eponymous children’s game. A player attempts to identify all the letters of a word in the mind of their opponent. Incorrect guesses contribute incrementally towards the sketch of a hanged man. As in Clown Torture, we see Nauman’s interest in the disturbing aspects of children’s entertainment. The original game has a gendered title, “Hangman: but the sex of the figure is not usually defined. By adding the genitalia, in accordance with the myth that an erection follows the death of a hanged man, Nauman gives his neon an erotic dimension in which sex and death are entwined. Nauman considers the theme of individual agency in this work.

Info: Curators: Andrea Lissoni, , Nicholas Serota, Katy Wan, Leontine Coelewij and Martijn van Nieuwenhuyzen, Tate Modern, Bankside, London, Duration: 7/10/20-21/2/21, Days & Hours: Daily 10:00-18:00 (All visitorsneed to book online in advance, www.tate.org.uk

Right: Bruce Nauman, The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (Window or Wall Sign), 1967, Neon tubing with clear glass tubing suspension frame, 1499 x 1397 x 51 mm, Kunstmuseum Basel, © Bruce Nauman / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2020, Courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York

Right: Bruce Nauman, One Hundred Live and Die, 1984, Installation view at Tate Modern 2020, Photo: Tate Photography (Matt Greenwood). Artwork © Bruce Nauman / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2020

Right: Bruce Nauman, Washing Hands Normal, 1996, Installation view at Tate Modern 2020, Photo: Tate Photography (Matt Greenwood). Artwork © Bruce Nauman / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2020