ART-PRESENTATION: The Sky as a Studio. Yves Klein and his contemporaries

In a world marked by the still-present memory of the Second World War, and in the context of the Cold War and the atomic threat, artists started abandoning traditional techniques in favour of actions or performances where the intensity of life is ever present. Conversely, the use of monochrome, emptiness or light, the aspiration to a zone of silence, collective and festive manifestations are also part of another perception of the world, marked by reconstruction and the birth of new utopias.

In a world marked by the still-present memory of the Second World War, and in the context of the Cold War and the atomic threat, artists started abandoning traditional techniques in favour of actions or performances where the intensity of life is ever present. Conversely, the use of monochrome, emptiness or light, the aspiration to a zone of silence, collective and festive manifestations are also part of another perception of the world, marked by reconstruction and the birth of new utopias.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Centre Pompidou Metz Archive

The exhibition “The Sky as a Studio. Yves Klein and his contemporaries” at Centre Pompidou-Metz is devoted to Yves Klein, a major figure on the post-war French and European art scene. Beyond the Nouveaux Réalistes movement, Yves Klein developed close ties with a whole host of artists, from the spatial artists in Italy to the ZERO and NUL groups in Germany and the Netherlands. He also maintained certain affinities – albeit more distant and less assertive – with the Gutai group in Japan. Alongside these groups, Yves Klein, the “space painter”, took art into a new dimension where the sky, the air, the void and the cosmos are an immaterial workshop conducive to reinventing man’s relationship with the world, after the tabula rasa created by the war. “The Sky as a Studio. Yves Klein and his contemporaries” proposes a dialogue between the works of Yves Klein and those of his contemporaries, highlighting their historical ties as well as their aesthetic and philosophical affinities. The thematic journey gives an account of the evolution of a generational artistic practice, which operates a passage from the material to the immaterial, from the visible to the invisible, from the earth to the sky, from the human body to the cosmos. Taking the ruins of the war as a starting point, the journey gradually leads the visitor into space, the dreamed of studio of these artists. The scenography highlights the process of dematerialisation that took place at the turn of the 1960s. In the manner of spatialist works that go beyond the limits of the canvas to open them up to another dimension, the curved walls and blurred edges render obscure the boundary between the work and the spectator. The exhibition layout aims to create immersive environments, where the artists’ research around immaterial and natural elements becomes meaningful.

SECTION I-THE WORLD YEAR ZERO: Whilst the Second World War left devastated landscapes and ruined monuments, this dilapidated topography became a breeding ground for creativity. In Germany, where “zero hour” was decreed, the massive destruction prompted artists, such as the members of the future ZERO group, to create new art on the rubble. In 1956, Jiro Yoshihara, wrote in the manifesto of the Gutai (meaning “concrete” in Japanese), group he founded in 1954, “when we allow ourselves to be seduced by the ruins, the dialogue initiated by the cracks and crevices may well be the form of revenge that the material has taken to recover its original state”.

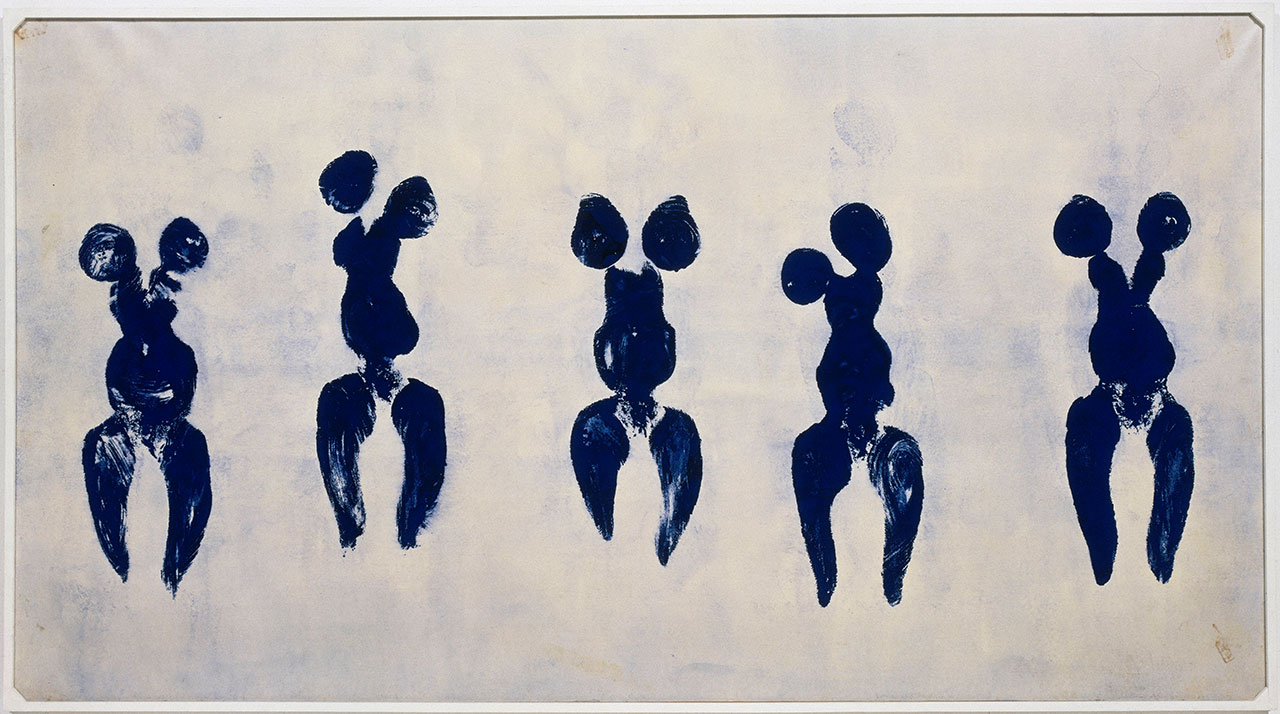

SECTION II-INTENSIVE BODIES: In Japan, the bombing of the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the summer of 1945 transformed the ethereal stillness of the sky into a place of atomic threats where the din of the explosions resounded. The film “Il est toujours bon de vivre” directed by Fumio Kamei, discovered by Yves Klein when it was released in 1956, shows the silhouettes, scorched onto the walls, of the bodies blown up by the bombs. “We must – and this is no exaggeration – realise that we live in the atomic age, where everything material and physical can disappear overnight…” warned Yves Klein. This revelation of the ephemeral is part of the upheavals in the visual arts initiated by a whole generation of artists and opens the way to immaterial art, at the crossroads between painting and performance. Klein’s “Anthropometries”, imprints left on the canvas by nude female models previously covered with pigments, Kazuo Shiraga’s inspired struggle with matter in “Challenging Mud” (1955), or the Footprints spread over the ground by Akira Kanayama in “Footprints” (1956), appear to be proof of the survival of the individual. Artists seem to be seeking to imprint themselves more literally on the world in order to fight against the inescapable disappearance of the being.

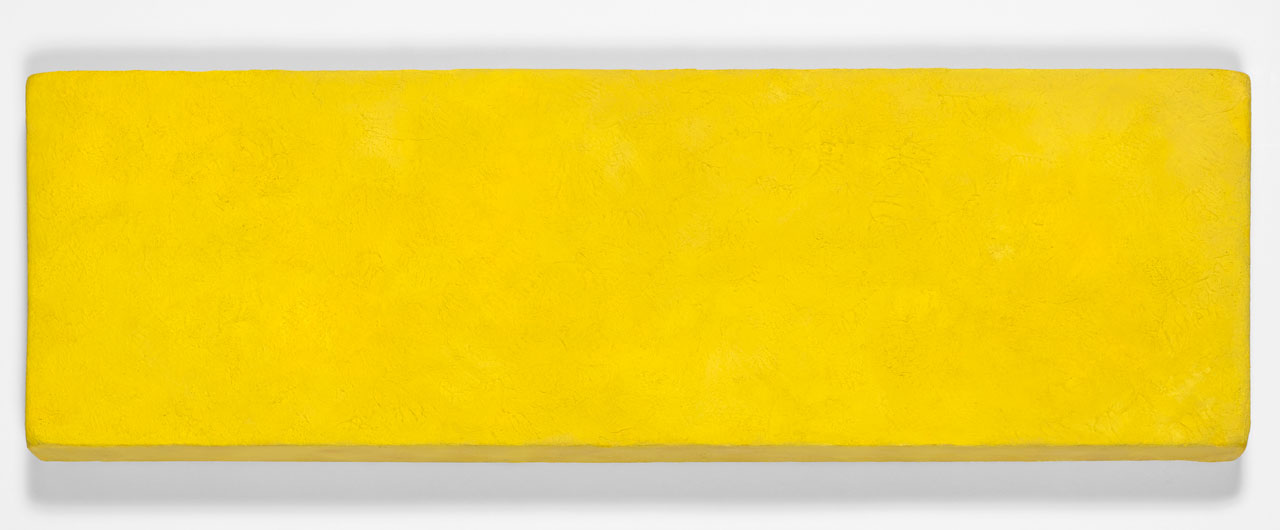

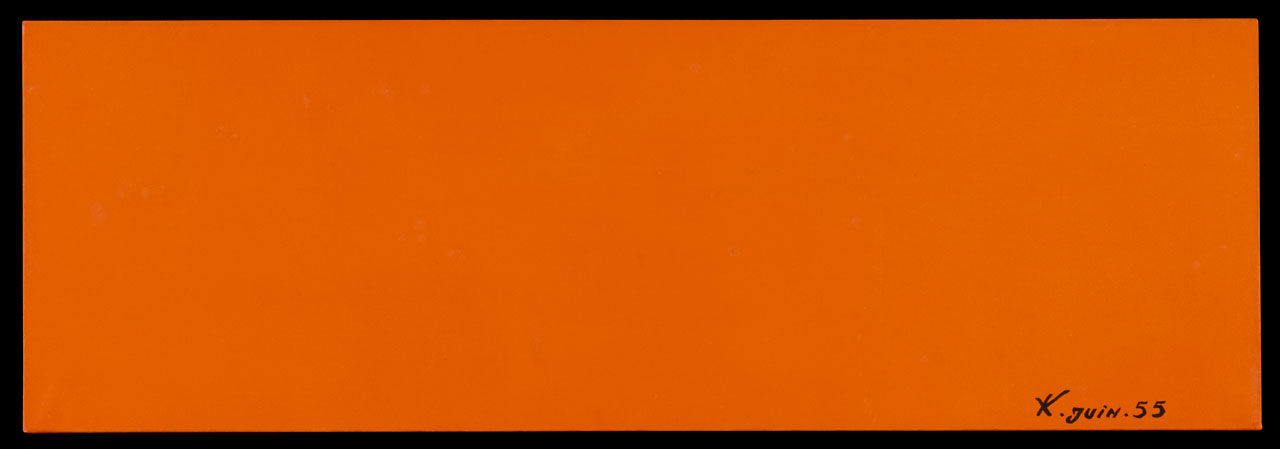

SECTION III-WHITE ZONES: From 1961 to 1966, a dozen group exhibitions took up the theme of white monochrome, attesting to the diversity of its developments. A symbol of purity and rebirth, white meets the aspirations of artists who want to wipe out the past. Whether it implies the invisible, the infinite, silence, space or light, it allows the total liberation of the surface. Applied rigorously on a canvas or more broadly on walls, it invades the space of representation in which the spectator is invited to enter. If Kasimir Malévitch was the first to experiment with monochrome, by exhibiting his “White on White” in 1918, it was only after the war that a generation of artists, set out to rewrite the world on this blank page of history. As early as 1946, Lucio Fontana inspired the publication of the Manifiesto Blanco, which laid the foundations of his spatialist theory, a new artistic concept aspiring to go beyond the flatness and materiality of the surface. Under the aegis of this tutelary figure, the new Milanese generation was able to discover Klein’s first blue monochromes as early as 1957 at the Galleria Apollinaire. Piero Manzoni, wanting to abolish colour, then gave birth to his white works, which he generically named “Achromes” in 1959. Made of kaolin, fibreglass, pleated fabrics or woven cotton, Manzoni’s “Achromes” do not involve painting and exclude interpretation. With Enrico Castellani, who shares this same need for white, Manzoni creates “Azimut(h)”, a gallery and magazine that from 1959 would be the instrument of their exchanges and collaborations with the European and Japanese groups that would participate in the monochrome adventure. In France, Claude Bellegarde produced white monochromes as early as 1951, revealing a spiritual quest that was not without influence on Klein’s work. In 1957 he began a series of 13 white monochromes, which he completed in 1960, and which prefigured the immaterial space of the Void, which took place in April-May 1958 at the Iris Clert Gallery in Paris. Created in 1961 for his first institutional retrospective (Yves Klein: Monochrome und Feuer, at the Museum Haus Lange in Krefeld, Germany), the “Empty Room”, a completely void room entirely covered with white paint, appears to be another absolute manifestation of this ethereal expansion. As a homage to Yves Klein’s “Vide”, Günther Uecker performed at the event “Zero. Edition Exhibition Demonstration” at the Schmela Gallery in Düsseldorf on 5th July 1961. Equipped with a “broom-paintbrush”, he drew a large white circle on the cobblestones, designed as a take-off runway leading to the new mysteries and artistic creations of his time. From the beginning, ZERO had always referred to it as “a zone of silence and pure possibilities for a new beginning, as in the countdown when the rockets take off”. For Otto Piene and Heinz Mack, the founders of ZERO, white is coveted for its structuring capacities that promote the vibration of the pictorial surface and are part of their search for the exaltation of light. For Uecker and Klein, the color white is conducive to a spiritual experience, and can also reveal other forces.

SECTION IV-PIERCING THE SKY: In the post-war period, artists showed a willingness to go beyond painting and canvas and to experiment with new materials. The use of fire as a medium was a response to this quest to dematerialize the work of art. Alberto Burri was one of the first European artists to integrate this element into his paintings: he burned the support of his works as early as 1955, before turning to “Combustioni plastiche” which intensified from 1961 onwards. That same year, the concomitant research of Yves Klein, Otto Piene and Bernard Aubertin led to the creation of fire paintings. A destructive and creative force, fire fascinated these artists because of its symbolic power. Yves Klein, as a demiurge artist, was passionate about this element, as powerful as it is fleeting, which allowed him to capture in a poetic event the very essence of the life that his works bear the memory of: “My paintings are only the ashes of my art”. These experiments echo the research of Italian artists Lucio Fontana and Dadamaino. Fontana, after having laid the foundations of an art “based on the unity of time and space” as early as 1946, is the inventor of “Buchi” (1949) and “Tagli” (1958), philosophical expressions of a space open to infinity. Inspired by a creative context that advocates a new beginning from scratch, Dadamaino pierces the canvas to the point of leaving only the edges, in a radical gesture of exploration of emptiness and immateriality. This quest for infinity expresses a reflection on the vastness of the cosmos, as suggested by Otto Piene’s poetic invitation, which shows how the radicality of Fontana’s gestures has been decisive for a whole new generation of artists: “When will we make a hole in the sky, Lucio Fontana?”

SECTION V-VOID THEATRES: During his collaboration at the Gelsenkirchen opera-theatre building site, where between 1958 and 1959 he produced four monumental panels in IKB blue, Yves Klein discovered the exceptional qualities of pictorial sensitivity projected on a monumental scale. The artist’s physical involvement in this in situ production resonates with the physicality at work in the Anthropometries sessions, also central to the gestures of Lucio Fontana, Saburō Murakami and Günther Uecker. The opening of the painting into an infinite space, at the heart of spatialist research, leads here to a performative dimension on a larger scale. The body finds itself projected into space – that of the work, its environment, and finally, the sky itself. The central space of the exhibition, an elevated structure offering the public an overhanging viewpoint, formalises the desire for ascent. In the context of the conquest of space, the artists develop their own means of occupying celestial space in a peaceful manner: an immaterial film projected on a balloon (Gil J. Wolman), inflatable sculptures (Yves Klein, Piero Manzoni, Otto Piene, Jean Tinguely) and magnetic sculptures (Takis), an exhibition in the sky organised by Gutai.

SECTION VI-AIR ARCHITECTURE: Upon his return from Gelsenkirchen in 1959, inspired by his large-scale work and his collaboration with Werner Ruhnau, Yves Klein developed the project of an Air Architecture. This immaterial architecture aimed to build the city of tomorrow from the natural elements of fire, air and water. His main research centred upon the roof of air, which was to replace the closed roof, this “shield that separates us from the sky, from the blue of the sky” and which enables the protection of its inhabitants without creating dividing walls. Klein continued the development of this aerial architecture with Claude Parent, who produced the drawings. The inhabitants of this “immense cosmic house” were to be freed from all constraints and devote themselves exclusively to leisure activities. The collaboration between Klein and Parent gives substance to Fontana’s desire to see a “fusion of artists and architects in the ‘architecture-space’ relationship. Parallel to Klein’s research, other artists were imagining utopian architectural projects: Gyula Kosice was designing plans for a hydrospace city floating at an altitude of more than 1,000 metres that used hydraulic energy as a building material, and Constant was working on the New Babylon, a city of suspended spaces whose inhabitants were also freed from work thanks to automation. These projects were part of a context of reconstruction and development of cities that was favourable to architectural utopias.

SECTION VII-COSMOGONIES: In his White Manifesto, Lucio Fontana declared that “art nouveau draws its elements from nature”. Even before the emergence of Land Art, a generation of artists integrated natural phenomena and forces into their work, flirting with chance, the unfinished, even the shapeless. This reappropriation of nature transcribes a cosmogonic and phenomenological vision of art, where forms and elements refer to a cosmic whole, which is expressed in its constant immediacy. The sharing of the world that Klein concluded during the summer of 1947, in Nice, with his artist friends, Claude Pascal and Armand Fernandez, the future Arman, testifies to a desire to appropriate the inappropriable: to Arman goes the earth and its riches, to Claude Pascal the air, and to Yves Klein, the painter of blue, the sky and its infinity. Later on, Tinguely would be given magnetism and Norbert Kricke water and light. In March 1960, in Cagnes-sur-Mer, Klein produced his first “Naturemétries” (as opposed to “Anthropometries”) or “Cosmogonies”, recording on sheets of paper the traces of plants impregnated with blue, or the passage of wind and rain, before fixing his signature on these “natural moments of being”. Hans Haacke also integrates water and air into his pieces, where natural phenomena intersect with social phenomena, while Heinz Mack is the painter of light. By exposing the pure IKB pigment on the floor, Klein focuses on the vibration of the color blue. Outdoor monumental and collaborative projects, such as the exhibition Zero op Zee conceived by artist Henk Peeters in 1965, which brought together artists from the groups ZERO, NUL and Gutai on the harbour pier in Scheveningen, in the Netherlands, articulating rationality and sensoriality, reflecting the emergence of new attitudes.

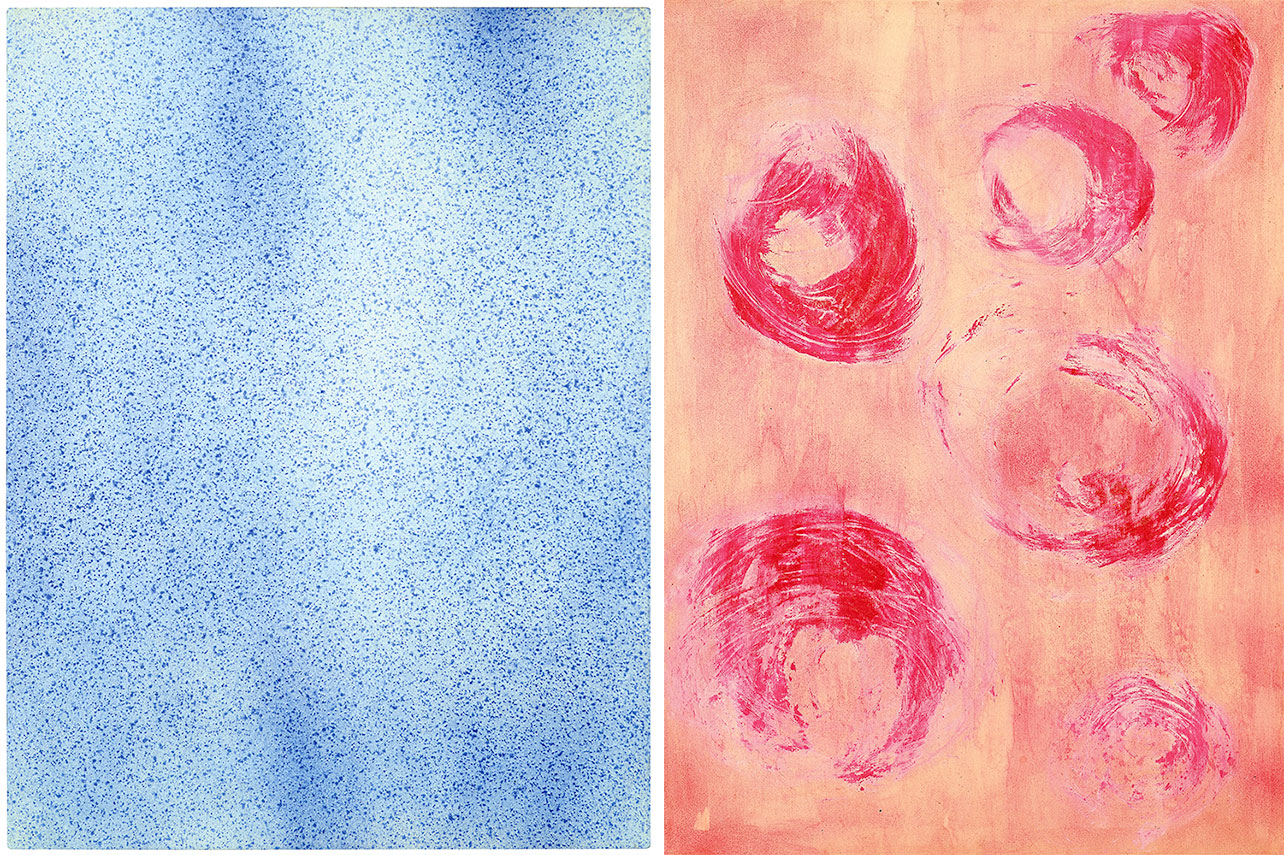

SECTION VIII-COLOURS INHABITING SPACE: Yves Klein and Sadamasa Motonaga had repeatedly expressed their desire to have their work performed outdoors. The occupation of public space was a theme dear to the artists of the Gutai group, who, as early as 1955, abandoned the traditional concept of an enclosed exhibition space in favour of the vast world with the infinite dome of the blue sky above. The ethereal space of nature offered infinite visual arts possibilities that also fascinated Yves Klein. Characterised only by a date, a place name and a dimension inscribed below, the uniformly pastel surfaces of Klein’s first monochromes, published in the portfolio “Yves peintures” in 1954, are reminiscent of atmospheric landscapes. The lithographs glued on paper appear soaked with the colourful climate of the city they are supposed to represent. For the artist, “colours are living beings, highly evolved individuals who integrate themselves into us, like everything else. Colours are the true inhabitants of space.” By choosing water as a binder, Motonaga also invites life to infiltrate his work. Clinging to the pine trees in Ashiya Park during the 2nd Outdoor Gutai Art Exhibition in the summer of 1956, the long membranes filled with coloured liquids remind us of cocoons, and the promise of the blossoming of colour. The tinted solutions, suspended in the air, are a challenge to gravity. For Klein, colour “bathes […] in cosmic sensitivity”. With their imperceptibly rounded edges and undulating surfaces, his monochromes with their indistinct contours create the sensation of a coloured nebula and recall the “marvellous rainbows” that Lucio Fontana dreamed of making appear in the sky at the same epoch.

SECTION IX-COSMIC VISIONS: The information brought back by Youri Gagarine upon his return from space in 1961 enchanted Yves Klein: he was right, the Earth is blue, an intense and deep blue. As early as 1957, when the Sputnik satellite was put into orbit, the “astronaut painter”, as Arman was nicknamed, produced a series of blue globes, reflecting this premonitory vision. In 1961, Klein continued his series of “Planetary Reliefs”, consisting of casts of topographical maps that he had acquired from the National Geographic Institute and covered with his IKB blue, giving his vision of a blue planet seen from the sky, like fragments of immeasurable space. The context of the conquest of space and the upheavals it brought to the representation of space in the broadest sense fascinated a whole generation of artists who aspired to reconquer the sky with their artistic sensitivity as their only weapon. Their works evolved in a natural way towards circular, spherical, ovoidal forms. These motifs, symbols of eternity and purity, evoke space in all its dimensions, from the microscopic to the infinite. The works of Otto Piene, Günther Uecker and Liliane Lijn, with their moving lights, share the same cosmic vision and offer a meditation on the place of the human being in the universe

On presentation are works by: Bernard Aubertin, Claude Bellegarde, Alberto Burri, Enrico Castellani, Constant, Dadamaino, Lucio Fontana, Hans Haacke, Oskar Holweck, Eikō Hosoe, Fumio Kamei, Akira Kanayama, Yves Klein, Gyula Kosice, Yayoi Kusama, Liliane Ljin, Heinz Mack, Piero Manzoni, Sadamasa Montanaga, Saburö Murakami, Claude Parent, Henk Peeters, Otto Piene, Giuseppe Pinot-Gallizio, Roberto Rossellini, Rotraut, Shözö Shimamoto, Fujiko Shiraga, Kazuo Shiraga, Takis, Jean Tinguely, Günther Uecker, Jef Verheyen, Lothar Wolleh and Gil J. Wolman

Info: Curators: Emma Lavigne and Daniel Moquay, Research and exhibition managers: Colette Angeli and Chloé Chambelland, Centre Pompidou Metz, 1 parvis des Droits-de-l’Homme, Metz, Duration: 18/7/20-1/2/21, Days & Hours: Mon, Wed-Thu 10:00-18:00, Fr—Sun 10:00-19:00 (Apr 1-Oct 31) or Mon & Wed-Sun 10:00-18:00 (Nov 1-March 31), www.centrepompidou-metz.fr