INTERVIEW: Yiannis Theodoropoulos

With Υiannis Theodoropoulos the years and the interests that unite us, are as many as our existence in the field of Art. We met for the first time in 1992, withinPhotography, and from that year we are moving forward, coexist, converse, negotiate and share our love and our anxieties about Life and Art. The hearth and home (House) for each of us is the most important and sacred, it is the sanctuary of the soul and the body, but for an artist like Giannis Theodoropoulos is the whole world, since for years he has been photographing it with a multi-level approach. On the occasion of the Covid 19 Pandemic and the global lockdown, we are talking about the goods of the house, that for some it is a curse and for others a blessing. For the majority of the people self-imprisonment is just a pause as the artist say and we completely agree with him. Α necessary pause to regroup, rethink and comeback wiser than ever.

With Υiannis Theodoropoulos the years and the interests that unite us, are as many as our existence in the field of Art. We met for the first time in 1992, withinPhotography, and from that year we are moving forward, coexist, converse, negotiate and share our love and our anxieties about Life and Art. The hearth and home (House) for each of us is the most important and sacred, it is the sanctuary of the soul and the body, but for an artist like Giannis Theodoropoulos is the whole world, since for years he has been photographing it with a multi-level approach. On the occasion of the Covid 19 Pandemic and the global lockdown, we are talking about the goods of the house, that for some it is a curse and for others a blessing. For the majority of the people self-imprisonment is just a pause as the artist say and we completely agree with him. Α necessary pause to regroup, rethink and comeback wiser than ever.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Yiannis Theodoropoulos’ Archive

In these difficult times that we are experiencing on the global level, the home is a safe haven for some, a prison for others. What is it for you Mr. Theodoropoulos?

I am having quite a pleasant time – reading, music, tai chi, meditation, films, telephone calls with friends who now have more time on their hands, and of course photography, which, as anyone who is familiar with my work knows, was always done at home. I did not have to wait for the coronavirus to turn inwards… But this is only a personal impression, I know well that the new reality has meant that many people have no work, and who knows how things will turn out in the months ahead. In any case, the ambience in my neighbourhood, where I take a walk every evening, is much quieter, as if people needed this pause… Pause – a magical word!

We know that you grew up in an unusual house, a stone-built villa in the working-class neighbourhood of Kato Pefki, surrounded by a lawn but no fence, on the American model, at the edge of a small wood. How did that differentiate you from other children, and what was the role of that house, and that difference, in your adult life?

Due also to certain legal complications (which have persisted for some 50 years!), I would say that this house has definitely marked me – emotionally, financially, and especially artistically. Yes, my mother did not want a fence, she preferred the American model, and from a very young age this gave rise to a feeling of external threat on my part, which has also persisted to this day. I still feel uncomfortable in my garden, which now has a fence of course; children from the nearby school sometimes toss stones inside, and this makes me angry, brings back unpleasant memories from my childhood, and I really don’t know how to handle it… Perhaps this is pay-back from my karma, there were things I also did myself when I was an adolescent, I was not a model boy.

Was this house built legally or was it an illegal construction? And how did this bipolarity, but also the bipolarities of interior – exterior, security – insecurity, private space – public space, affect you?

The house is absolutely legal, all the necessary permits and paperwork are in place, but it is situated at the edge of a small wood and the status of a small part of that is unclear, affecting my property. Ideally, I would like it to become a museum to house works from the small collection I have assembled, mainly through exchanges with my colleagues; or I could sell it and make a new start!

When did you start understanding all that, assimilating it, and using it in your work? The Greenhouse Series has always seemed to me like a warm womb, an embrace.

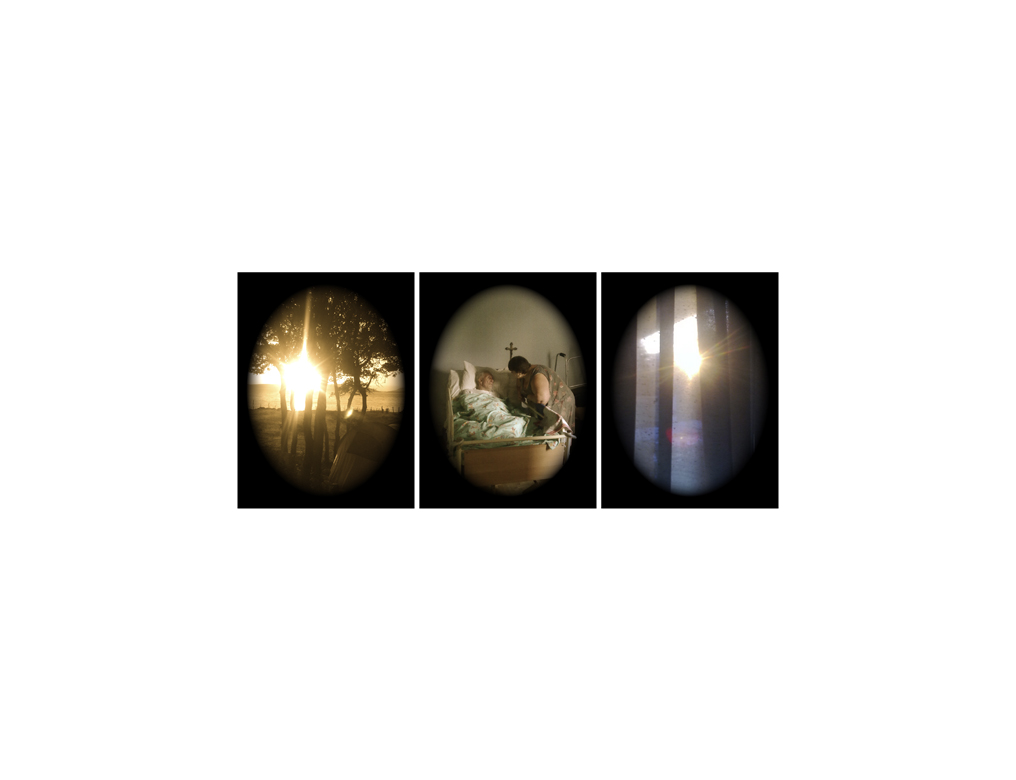

Looking back to the Greenhouse Series from a distance of almost 24 years (I think I started on that venture in 1996), the greenhouses seem like a prelude to all my subsequent work, a sense of sweet, luminous protection from the threatening “outside”; they seem quite relevant in the situation we find ourselves in now.

“I obsessively seek security, exploring the landscapes of the house beneath the tables, within clothes, on the furniture”. I am quoting your own phrase so we can decipher it here. Looking at those photographs I have always wondered how they came about and what they mean. They represent a puzzle for me, and perhaps for others, that we would like you to resolve for us.

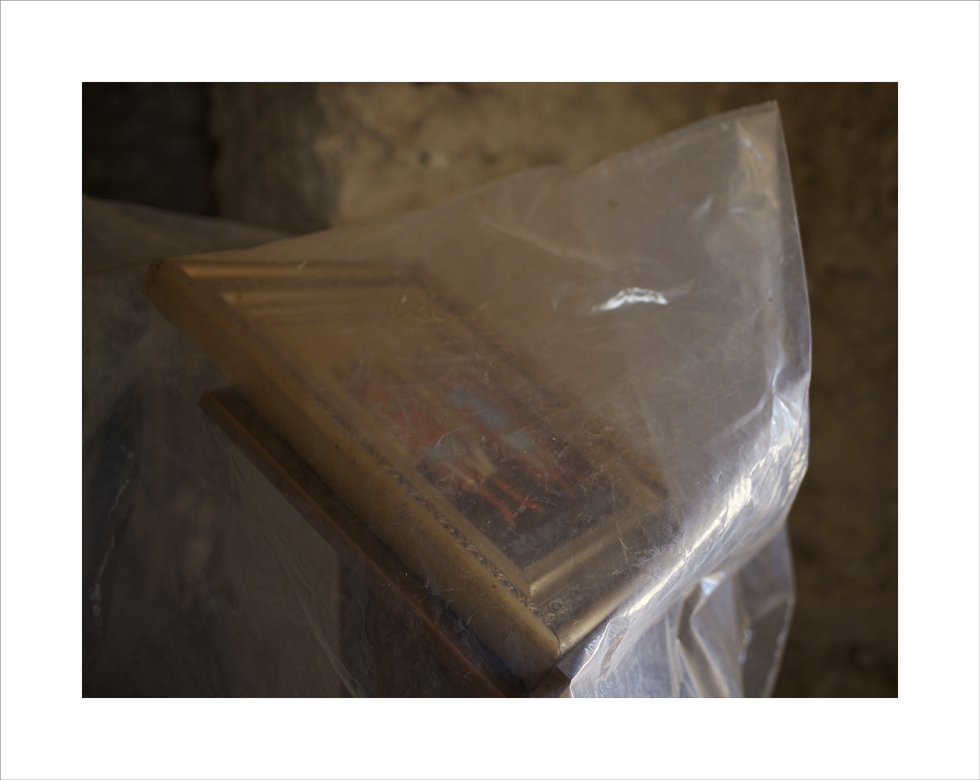

I have always felt like an explorer in my own home, discovering corners, objects, hidden places that the lens transformed into utopian landscapes. I had a particular obsession about certain pieces of furniture, the green sofa by Saridis, of which the pleats made me think of utopian green fields, the yellow settee, again by Saridis, on which I place my clothes because I never store them in cupboards. I was bored, meaning that all of my work was, and is, connected to my every-day life, which is why I call it Experiential Sculpture. There is a personal relationship with the objects I photograph or relocate in a different context, they are not random objects. I feel much closer to modern sculptors than to photographers, at least as concerns Greece. In the last two years I arrange certain objects and clothes on a table to photograph them, so there is an element of construction I could say, though again the objects are chosen through personal reminisces, whether earlier or recent; a diver’s suit, stones I have brought back from my travels to exotic destinations, postcards from places I have loved. I would say that my work is a process in which my internal world, the objects in my house, and of course the light, pursue an on-going dialogue redefining the present, the past and perhaps the future. Perhaps one part of my work focuses on a very personal universe and essentially seems like an autobiography constructed around objects, but I believe it might perhaps be relevant to many people that have similar cultural backgrounds. In any case, perhaps our personal space is the last haven for the holy, perhaps it has still escaped the transparency of evil. Perhaps…

In past years you, and all of us, had the freedom to embark on both inward and outside solitary wanderings and peregrinations in the city. Now we have been deprived of that freedom – what does that mean and how are you dealing with it? What did the metropolis signify a short time ago and what does it signify now?

In truth, the only things that I really miss are the sea and the walks I made with my friend Dimitris in the Royal Estates.

Does “Experiential Sculpture” include those images from your family home? What does family mean for you and what was the role of your family (with two women, your mother and your aunt, who had very strong personalities) in your life and your work?

It is true that my mother, despite the fact that when she was 40 she retreated into the house and never ventured out again (a pioneer, considering the current situation!) was a highly intelligent woman. If family and social conditions had allowed it, she might have excelled in some fields, which is why I consider inexcusable this surrender of hers to the circumstances of fate. I was very moved when a friend from the old days whom I met again recently told me that the most interesting conversations he has ever had were with my mother.

How much and in what ways has this unprecedented situation we are experiencing with the coronavirus affected you, and how are you dealing with it in your work?

The crisis has not affected me very much on the personal level. I have continued to work as usual. But whether it has affected some artists, and in what ways, will be seen much later. Art is, or at least should be, a slow, internal process.

I would like to close this very interesting discussion with a saying attributed to Tibetan monks: “Crisis is a wake-up call”. What, if anything, do you think will be different afterwards?

I agree with the Tibetan monks, it is an opportunity for those who live alone to consider what they have accomplished with themselves in all this time and for those who live with others to consider what they have accomplished with their partners and their children. I would like here to stress once again that I am referring to people who do not face any immediate health problem or financial difficulties. Things are different then, and would require another sort of discussion, concerning the entire planet. But such a discussion is outside the scope of an interview like this one.

Cover Photo: Yiannis Theodoropoulos, Self-portrait with T-shirt of T-shirτ of Greeκ Hellenic Football Federation, 2014, inkjet print on aluminium frame, 180x165cm, © Yiannis Theodoropoulos, Courtesy the artist

Download Greek Version of Interview here.

First Publication: www.dreamideamachine.com

© Interview-Efi Michalarou