ART-TRIBUTE:Donald Judd-Judd

Donald Judd was among a generation of artists in the 1960s who sought to entirely do away with illusion, narrative, and metaphorical content. He turned to three dimensions as well as industrial working methods and materials in order to investigate “real space”. To Judd, his works, which he called “specific objects,” were neither paintings nor sculptures but simply autonomous objects which were merely self-referential since they did not represent anything else. These objects were created using everyday industrial materials with the intention of eliminating any kind of personal imprint.

Donald Judd was among a generation of artists in the 1960s who sought to entirely do away with illusion, narrative, and metaphorical content. He turned to three dimensions as well as industrial working methods and materials in order to investigate “real space”. To Judd, his works, which he called “specific objects,” were neither paintings nor sculptures but simply autonomous objects which were merely self-referential since they did not represent anything else. These objects were created using everyday industrial materials with the intention of eliminating any kind of personal imprint.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: MoMA Archive

“Judd” is the first major US retrospective dedicated to the work of Donald Judd in over three decades. The exhibition explores the remarkable vision of an artist who revolutionized the history of sculpture, highlighting the full scope of Judd’s career through 70 works in sculpture, painting, drawing, and prints, from public and private collections in the US and abroad. The retrospective explores the work of an artist who changed the course of modern sculpture. Born in Excelsior Springs, Missouri, Donald Judd began his career as an abstract painter in New York City in the mid-1950s, but in 1962 he began to work in three dimensions. By the mid-1960s he had begun to develop a distinctive and intentionally narrow vocabulary, articulating objects that occupied, as Judd said, “real space”. The apparent simplicity of Judd’s works has long provoked suspicion as to whether they are actually “art.” They were made to Judd’s specifications by outside fabricators rather than by his own hand or those of assistants in his studio. Evidence of personal gesture is absent, as is any direct or symbolic reference to the human figure. Judd’s materials come from industrial or utilitarian contexts rather than those of fine art. Colors are those native to a given material, or commercially applied to seem so. Fundamentally, the works challenge prior assumptions regarding sculpture’s solidity and weight. They are concerned more with space than with mass: his objects implicate the space within, between, and around their component units. Judd resisted the word “sculpture,” believing that his innovations set his work apart from historical precedent. Whatever the terminology, it put sculpture at the forefront of artistic experimentation in the 1960s and lifted it from its longtime position as secondary to painting. Judd’s activities over the course of three decades extended far beyond the realm of making works of art. He was a prolific essayist, an innovator in the fields of architecture and design, and deeply committed to democratic and environmental causes. Half a century later, the radical ramifications of Judd’s achievement continue to unfold.

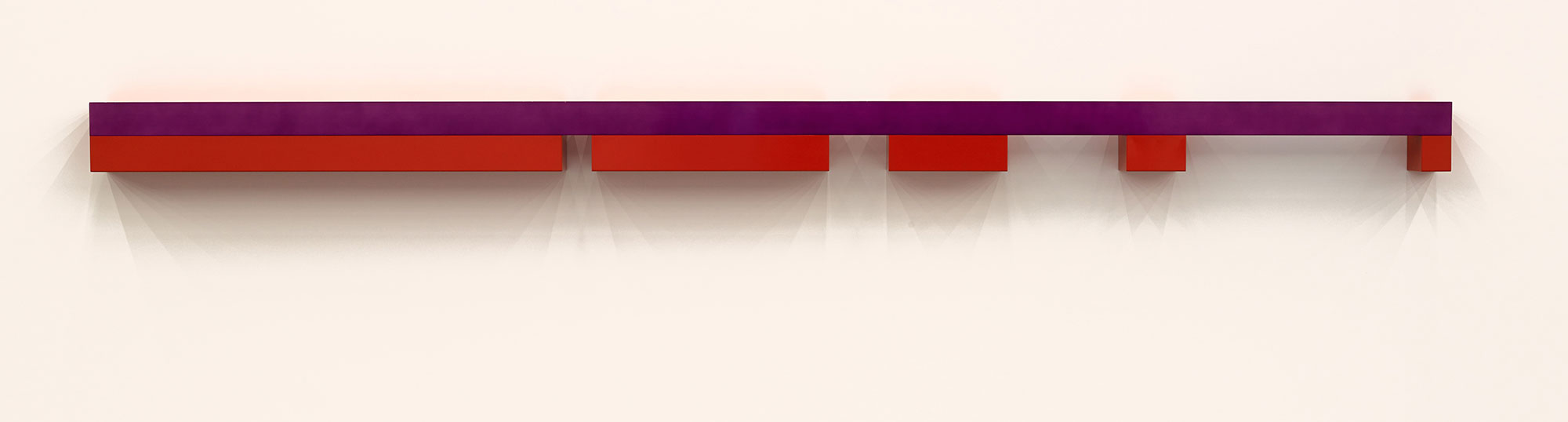

During the early years of his career, Judd was more visible as an art critic than as an artist, publishing nearly 600 reviews from 1959 to 1965. While working as a critic, Judd gradually intensified the threedimensionality of his paintings and began to incorporate found elements. Judd soon enlisted his father, a skilled carpenter, to help him make wall reliefs and freestanding box-like forms, using wood, metal, and materials sourced from odds-and-ends vendors. “I spent a lot of time looking around,” he later recalled. “I’d see a nice piece of aluminum tubing or a strip of plastic on Canal Street and I’d buy it”. In 1963, Judd debuted these objects in two group shows, and then a solo exhibition, at the trailblazing Green Gallery. Most of the works were painted in cadmium red light, a color that Judd said he chose because it “really makes an object sharp and defines its contours and angles”. Judd was not fully satisfied with the cumbersome process of making his three-dimensional objects, or the homemade look of their painted wooden surfaces and found materials. A breakthrough occurred in early 1964, when the artist walked into Bernstein Brothers Sheet Metal Specialties, a shop near his loft. Judd learned that the metalworkers there could produce his objects to order, working from his detailed instructions to form the sheet metal they normally used for products such as industrial sinks and ventilation ducts into works of art. During the intensely fruitful months that followed, Judd explored various new formats and materials for the thin, hollow units he could have made by Bernstein. Among the first objects produced in that period, were a collapsible floor box comprising three frosted amber Plexiglas sides and two steel endplates, held together by the tension of interior wires and turnbuckles, and a wall work consisting of four galvanized iron boxes of the same dimensions connected by a blue aluminum bar.

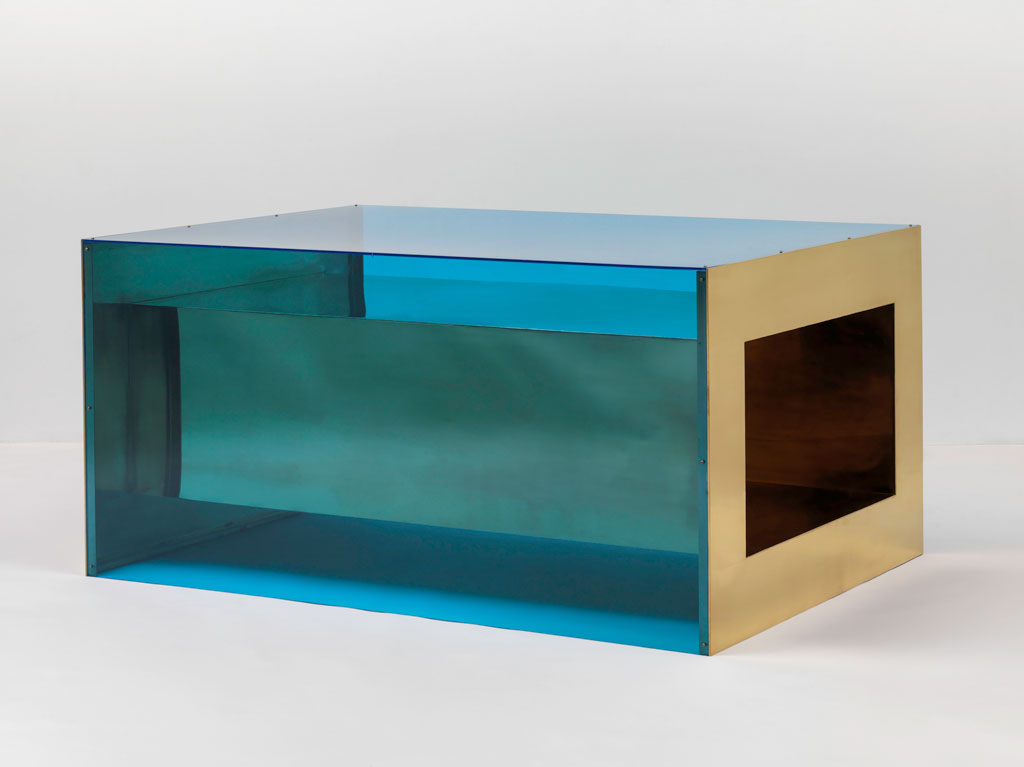

Judd had his first solo museum exhibition in 1968, at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. The show featured an open layout of 30 objects that introduced the public to Judd’s commitment to basic forms free of metaphorical or expressive intent. It served to identify Judd as the leader of a “Minimalist” movement made up of artists who shared a pared-down aesthetic, an interest in repeating forms, and the use of industrial materials and methods. Included in addition to the “stacks” were wall works known as “progressions” which consist of a hollow bar connecting a number of L-shaped box units whose respective lengths (and, in reverse, the distances between them) correspond to a mathematical logic such as simple doubling or the Fibonacci sequence. “Bullnose” progressions feature units with rounded profiles. In the early 1970s, Judd began to engage space in new ways, making works that responded to the specific parameters of a given room. In gallery installations, as well as in pieces commissioned for particular indoor or outdoor sites, he investigated the ways in which an object defines the space it occupies. He started making work in plywood, an affordable and utilitarian material (available in large sheets) that resonated with the architectural nature of his work. Judd also began to make expansive multi-unit pieces, such as the twenty-one-part floor work in this gallery, in which each unit has a unique configuration. This evolution of the works’ scale and reference to site corresponded to a dramatic shift in Judd’s circumstances: he was recentering his practice in Marfa, a small town in West Texas long past its economic heyday. There Judd acquired buildings and land large enough to satisfy his need for space to situate his art. Over the next two decades, he established permanent installations of his work and that of selected peers, in what he saw as a necessary counterpoint to the temporary displays at museums such as this one. Throughout his career, Judd retained a painter’s attention to color. The inherent colors of his materials offered an expansive palette, which he further enhanced with industrially applied paint and richly hued sheets of Plexiglas. Until the 1980s, however, Judd limited each of his works to one or two colors. Judd’s work took a decisive turn in 1984, when he began to work with Lehni AG, a Swiss manufacturer of aluminum products. The resulting multicolored works, inspired by the technology available at Lehni, are shallow, outward-facing open boxes of folded aluminum. The aluminum was powder coated in colors selected from the RAL color chart, a standardized resource for commercial and industrial use. Judd arranged the colors to achieve overall balance while avoiding patterns or the appearance of a system at play. “I wanted all of the colors to be present at once, I didn’t want them to combine. I wanted a multiplicity all at once that I had not known before”. At the same time, Judd continued to experiment with novel ideas for his signature forms, investigating new chromatic and spatial structures within his metal and plywood boxes. He was also deeply engaged with his writing, his projects for buildings, and new commissions. At the time of his death from cancer in 1994, at the age of 65, much remained to be done.

Info: Curators: Ann Temkin, Yasmil Raymond and Erica Cooke, MoMA-Museum of Modern Art), 11 West 53 Street, Manhattan, New York, Duration: 1/3-11/7/20, Days & Hours: Mon-Thu & Sat-Sun 10:30-17:30, Fri 10:30-21:00, www.moma.org

Right: Donald Judd. Untitled. 1989. Clear anodized aluminum with amber acrylic sheet, 100 × 200 × 200 cm. Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland © 2020 Judd Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: © Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art