TRACES: Ruth Asawa

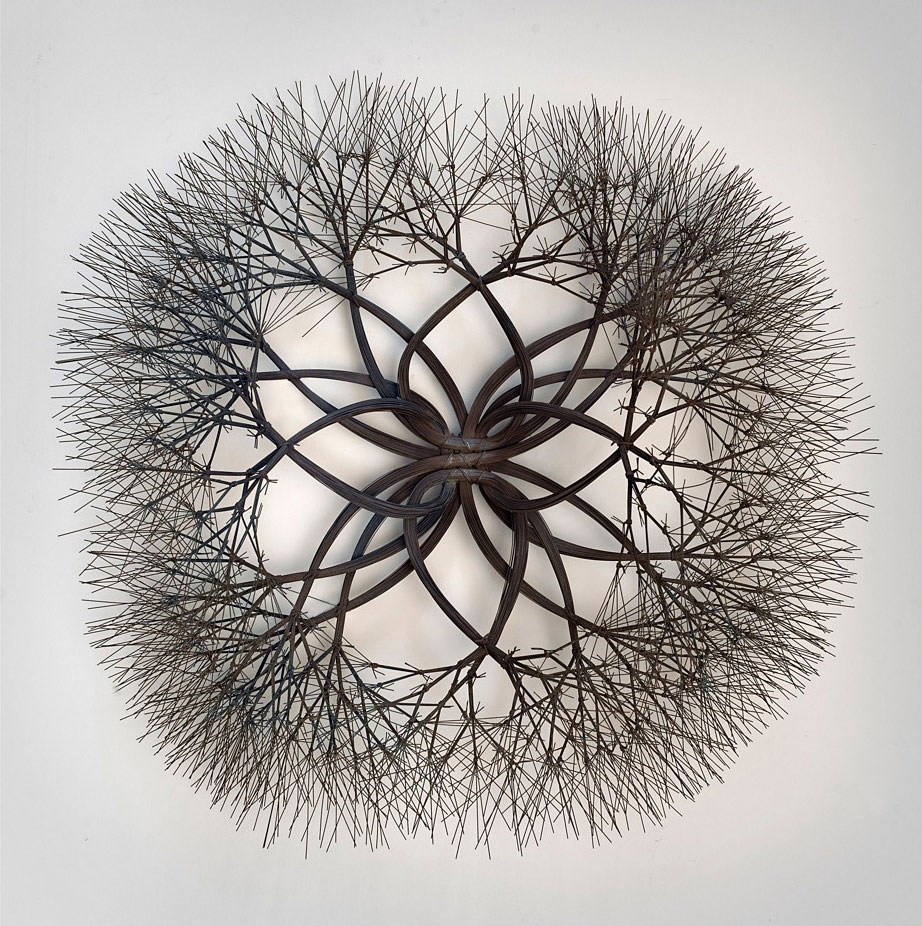

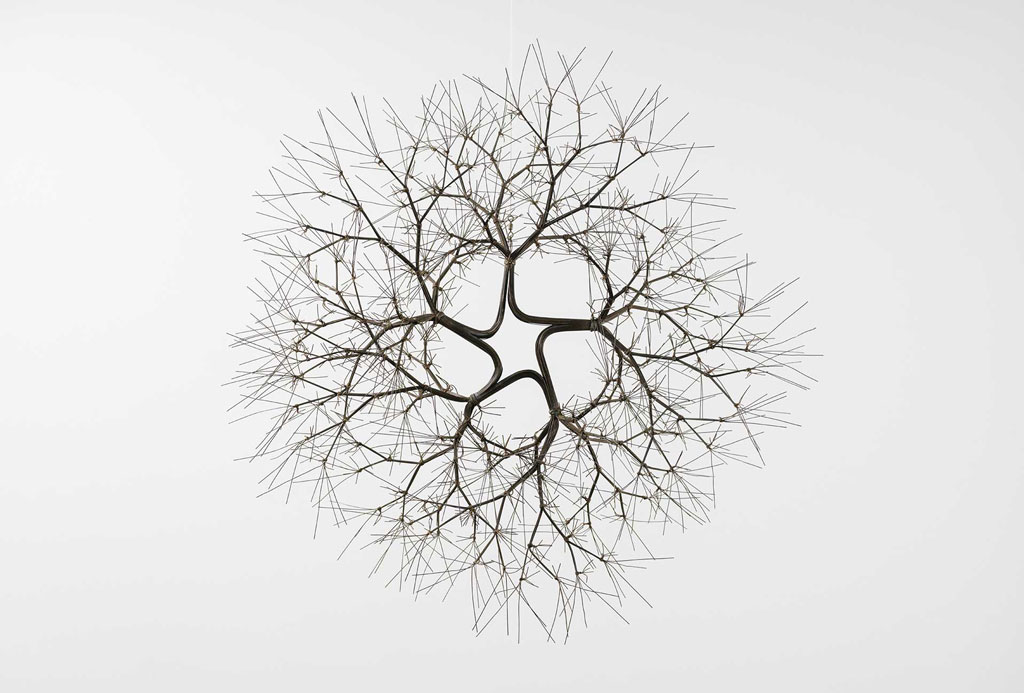

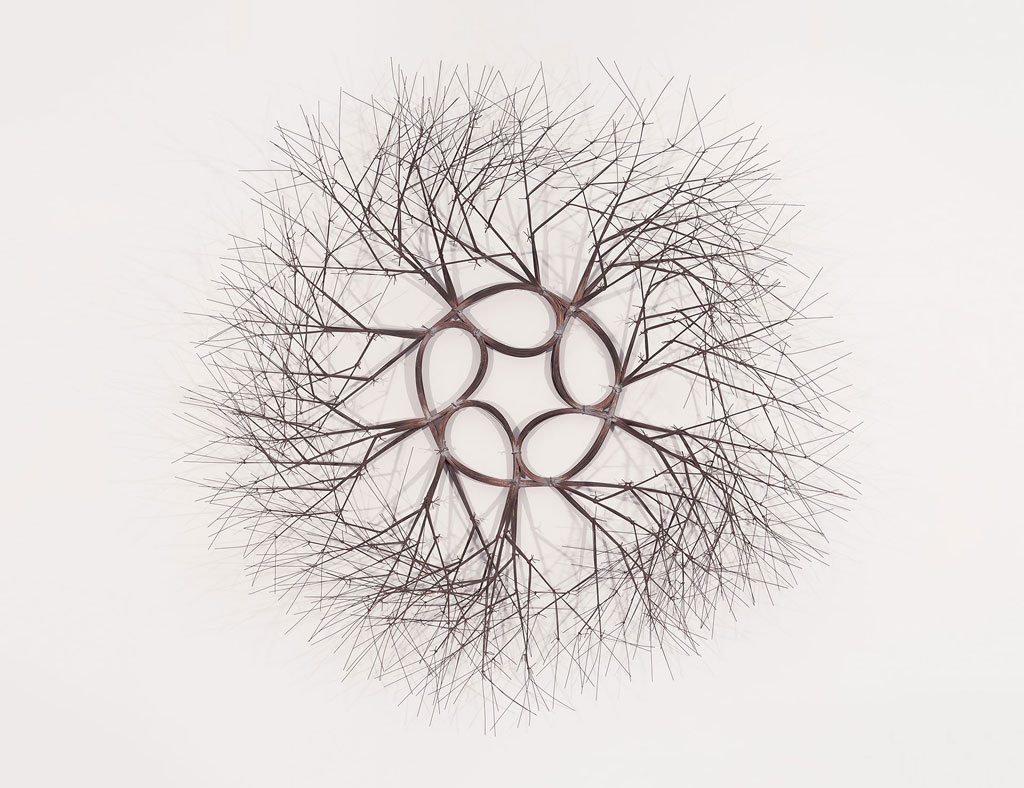

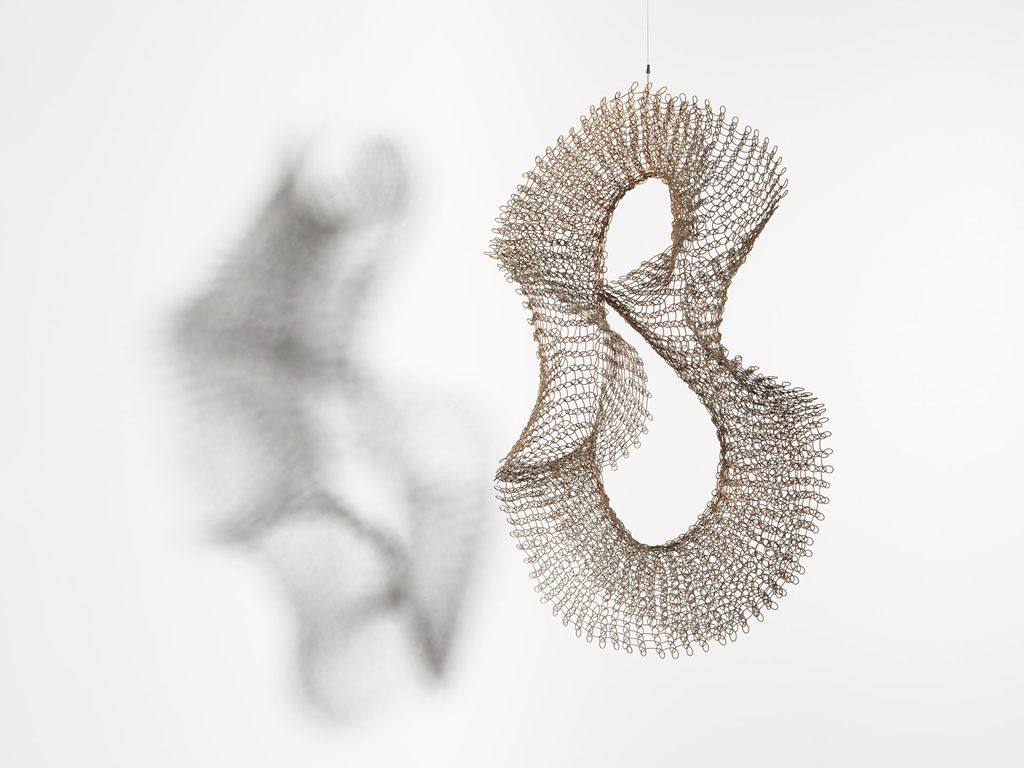

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Ruth Asawa (24/1/1926-5/8/2013), an artist best known for her sculptures “crocheted” from metal wire, figures she described as “drawings in space”, many of which were displayed suspended as mobiles. She later turned to large public projects and community activism. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Ruth Asawa (24/1/1926-5/8/2013), an artist best known for her sculptures “crocheted” from metal wire, figures she described as “drawings in space”, many of which were displayed suspended as mobiles. She later turned to large public projects and community activism. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Efi Michalarou

Ruth Asawa frequently cited her memories of growing up on a farm in California as an inspiration for her work. She was born in 1926 in Norwalk, California, one of seven children. Her parents, immigrants from Japan, operated a truck farm. In the hysteria following the outbreak of the World War II, the United States government feared that Japanese Americans would commit acts of sabotage against their country. Although no such act was ever committed by a Japanese American, some 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry living in the Western United States were removed from their homes and made to live in internment camps. Of these, almost 80,000 were United States citizens; 40,000 were children. Ruth Asawa was one of these citizen children. In February 1942, Ruth’s father Umakichi, a 60 year-old farmer who had been living in the United States for forty years, was arrested by FBI agents and taken to a camp in New Mexico. The family did not see him for almost two years. In April, Ruth was sent along with her mother and five siblings to the Santa Anita race track in Arcadia, California, where they lived for five months in two horse stalls. They took only what they could carry. Suddenly Ruth did not have to work long hours on the family farm, and she used her free time to draw. Among the internees were animators from the Walt Disney Studios, who taught art in the grandstands of the race track. In September, the Asawa family was sent by train to an internment camp in Rohwer, Arkansas, where Ruth continued to spend most of her free time painting and drawing. Ruth was fortunate because her period of incarceration lasted only eighteen months. A Quaker organization called the Japanese American Student Relocation Council gave her a scholarship to attend college in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. In August 1943, she was issued an identification card by the War Relocation Authority that permitted her to travel to Milwaukee. Ruth never returned to visit her family in Rohwer who were released from the camp in November 1945. She did not see her parents again until 1948. By the time Asawa arrived in Black Mountain College, in the summer of 1946, it had been in operation 13 years. Protected by its rural isolation, the college had succeeded in creating a safe environment where a truly individualized education was possible. Asawa’s time at Black Mountain proved formative in her development as an artist, and she was particularly influenced by her teachers: Josef Albers, Buckminster Fuller, and the mathematician Max Dehn. She also met architectural student Albert Lanier, whom she would marry in 1949 and with whom she would raise a large family and build a career in San Francisco. Josef Albers’ design courses taught Asawa the importance of relationships and the relativity of perception. These relationships were present among humans, among colors, between forms, figure and ground, positive and negative. It was because of her lessons from Albers that Asawa discovered a new use for wire on a visit to Mexico in 1947. A craftsman in Toluca, Mexico showed her how he made egg baskets by looping wire. Through experimentation, she would elevate this looping-wire technique from functional baskets to her original looped-wire sculptures. Her sculptures enclose space without masking it and incorporate shadow into the works themselves. Although the making of the looped-wire sculptures is a repetitive process, the conceptualization is complex and modern. In 1968, Asawa co-founded the Alvarado School Arts Workshop, with friend and fellow parent, Sally Woodbridge. It was an innovative program that involved parents and professional artists in the public schools so that young children had the chance to develop more fully as individuals. They started with almost no money and throwaway objects like milk cartons, egg cartons, scraps of yarn, and flour, salt and water. They spent the summer working with baker’s clay. It was a cheap and safe material to introduce children to sculpture. At about the same time, Asawa became a member of the San Francisco Arts Commission and began lobbying politicians and charitable foundations to support arts programs that would benefit young children and average San Franciscans. At its peak, the Alvarado School Arts Workshop was in 50 public schools in San Francisco. It employed artists, musicians, and gardeners and recruited thousands of parents to be involved in public education. Asawa would go on to serve on the California Arts Council, the National Endowment for the Arts, and become a trustee of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. As an arts advocate, her focus was always on arts education. Asawa was instrumental in founding the public arts high school in San Francisco in 1982. In 2010, the school was named the Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts in her honor. Her vision was that the school be located next to the ballet, opera, and symphony in the Civic Center arts corridor in San Francisco. Her time at Black Mountain College convinced her of the importance of giving students opportunities to work directly with professional artists.

Ruth Asawa frequently cited her memories of growing up on a farm in California as an inspiration for her work. She was born in 1926 in Norwalk, California, one of seven children. Her parents, immigrants from Japan, operated a truck farm. In the hysteria following the outbreak of the World War II, the United States government feared that Japanese Americans would commit acts of sabotage against their country. Although no such act was ever committed by a Japanese American, some 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry living in the Western United States were removed from their homes and made to live in internment camps. Of these, almost 80,000 were United States citizens; 40,000 were children. Ruth Asawa was one of these citizen children. In February 1942, Ruth’s father Umakichi, a 60 year-old farmer who had been living in the United States for forty years, was arrested by FBI agents and taken to a camp in New Mexico. The family did not see him for almost two years. In April, Ruth was sent along with her mother and five siblings to the Santa Anita race track in Arcadia, California, where they lived for five months in two horse stalls. They took only what they could carry. Suddenly Ruth did not have to work long hours on the family farm, and she used her free time to draw. Among the internees were animators from the Walt Disney Studios, who taught art in the grandstands of the race track. In September, the Asawa family was sent by train to an internment camp in Rohwer, Arkansas, where Ruth continued to spend most of her free time painting and drawing. Ruth was fortunate because her period of incarceration lasted only eighteen months. A Quaker organization called the Japanese American Student Relocation Council gave her a scholarship to attend college in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. In August 1943, she was issued an identification card by the War Relocation Authority that permitted her to travel to Milwaukee. Ruth never returned to visit her family in Rohwer who were released from the camp in November 1945. She did not see her parents again until 1948. By the time Asawa arrived in Black Mountain College, in the summer of 1946, it had been in operation 13 years. Protected by its rural isolation, the college had succeeded in creating a safe environment where a truly individualized education was possible. Asawa’s time at Black Mountain proved formative in her development as an artist, and she was particularly influenced by her teachers: Josef Albers, Buckminster Fuller, and the mathematician Max Dehn. She also met architectural student Albert Lanier, whom she would marry in 1949 and with whom she would raise a large family and build a career in San Francisco. Josef Albers’ design courses taught Asawa the importance of relationships and the relativity of perception. These relationships were present among humans, among colors, between forms, figure and ground, positive and negative. It was because of her lessons from Albers that Asawa discovered a new use for wire on a visit to Mexico in 1947. A craftsman in Toluca, Mexico showed her how he made egg baskets by looping wire. Through experimentation, she would elevate this looping-wire technique from functional baskets to her original looped-wire sculptures. Her sculptures enclose space without masking it and incorporate shadow into the works themselves. Although the making of the looped-wire sculptures is a repetitive process, the conceptualization is complex and modern. In 1968, Asawa co-founded the Alvarado School Arts Workshop, with friend and fellow parent, Sally Woodbridge. It was an innovative program that involved parents and professional artists in the public schools so that young children had the chance to develop more fully as individuals. They started with almost no money and throwaway objects like milk cartons, egg cartons, scraps of yarn, and flour, salt and water. They spent the summer working with baker’s clay. It was a cheap and safe material to introduce children to sculpture. At about the same time, Asawa became a member of the San Francisco Arts Commission and began lobbying politicians and charitable foundations to support arts programs that would benefit young children and average San Franciscans. At its peak, the Alvarado School Arts Workshop was in 50 public schools in San Francisco. It employed artists, musicians, and gardeners and recruited thousands of parents to be involved in public education. Asawa would go on to serve on the California Arts Council, the National Endowment for the Arts, and become a trustee of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. As an arts advocate, her focus was always on arts education. Asawa was instrumental in founding the public arts high school in San Francisco in 1982. In 2010, the school was named the Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts in her honor. Her vision was that the school be located next to the ballet, opera, and symphony in the Civic Center arts corridor in San Francisco. Her time at Black Mountain College convinced her of the importance of giving students opportunities to work directly with professional artists.