TRACES: Eva Hesse

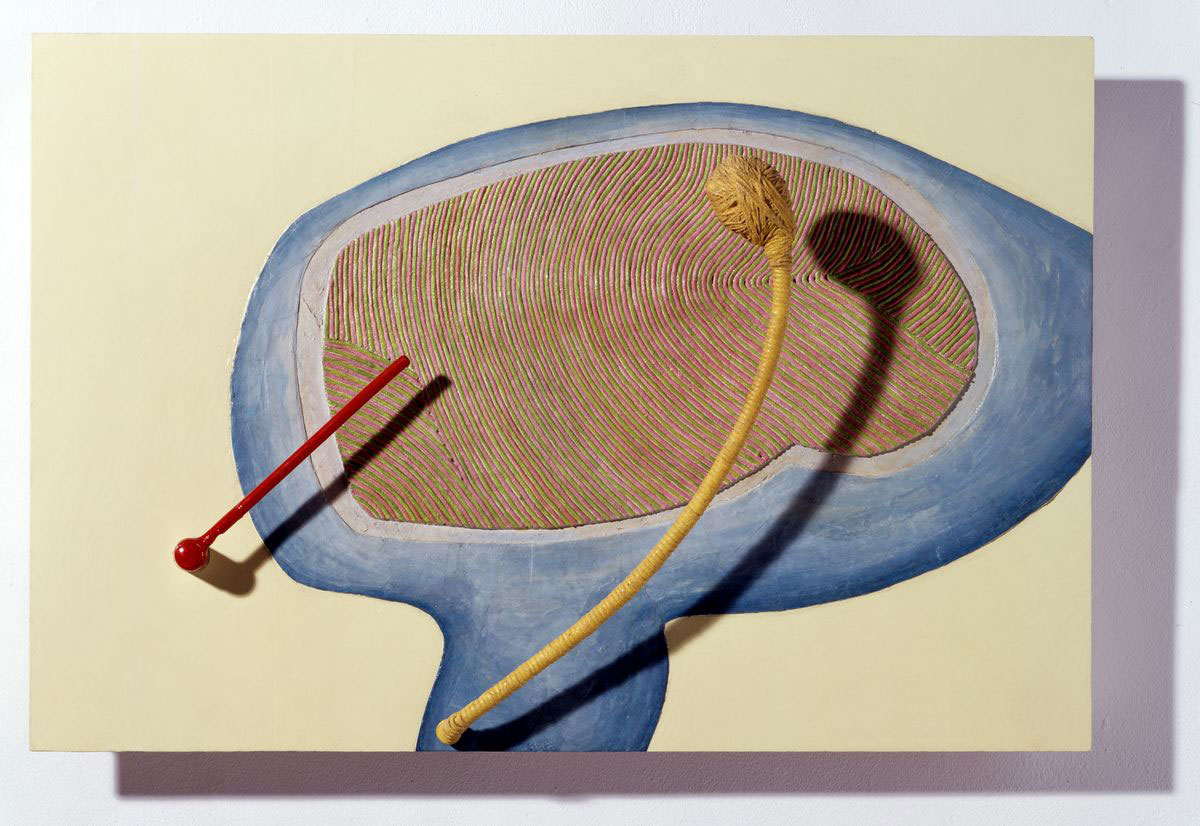

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Eva Hesse (11/1/1936-29/5/1970). She was one of the great artists of the 1960s, and her major sculptural works stand out as singular achievements of that era. At once drawing on Minimalist strategies of repetition and seriality, and pushing nontraditional materials toward new modes of expression, Hesse created an art that evoked emotion, absence, and contingency. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Eva Hesse (11/1/1936-29/5/1970). She was one of the great artists of the 1960s, and her major sculptural works stand out as singular achievements of that era. At once drawing on Minimalist strategies of repetition and seriality, and pushing nontraditional materials toward new modes of expression, Hesse created an art that evoked emotion, absence, and contingency. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Efi Michalarou

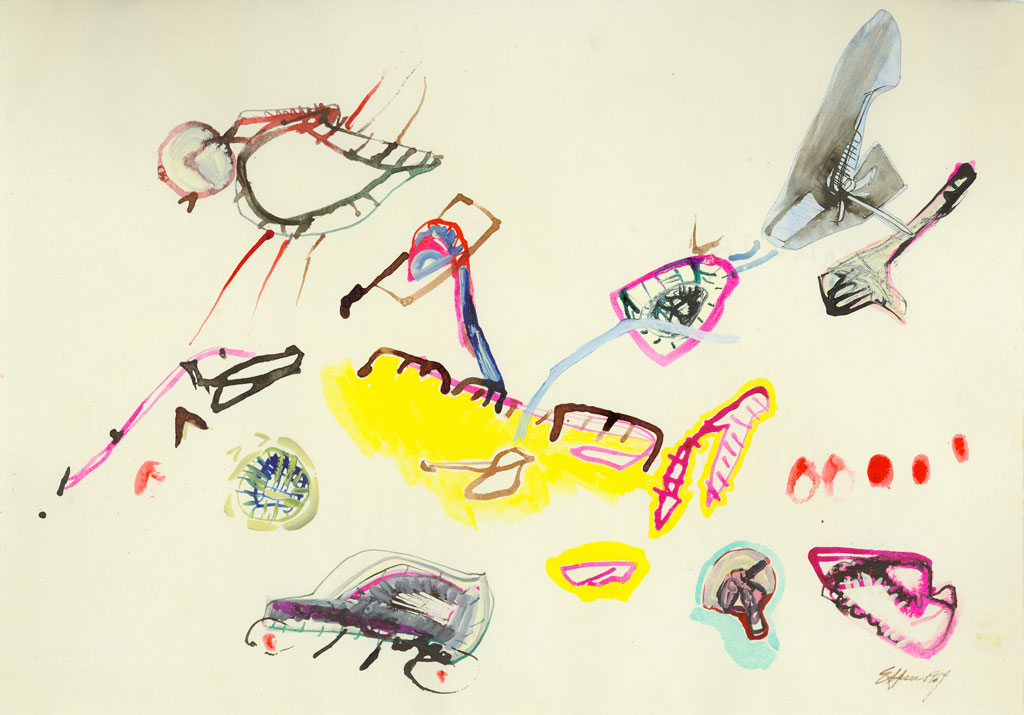

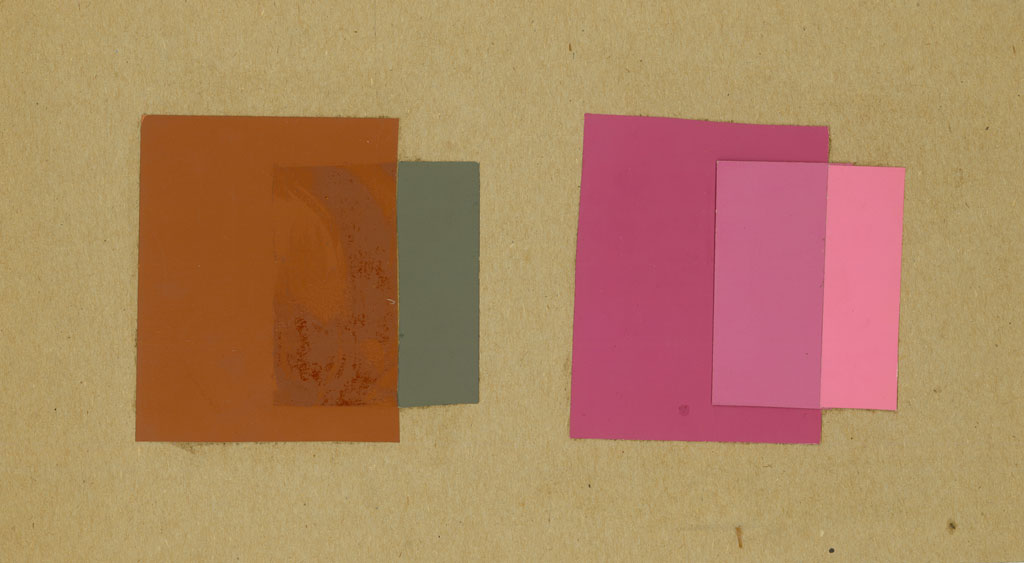

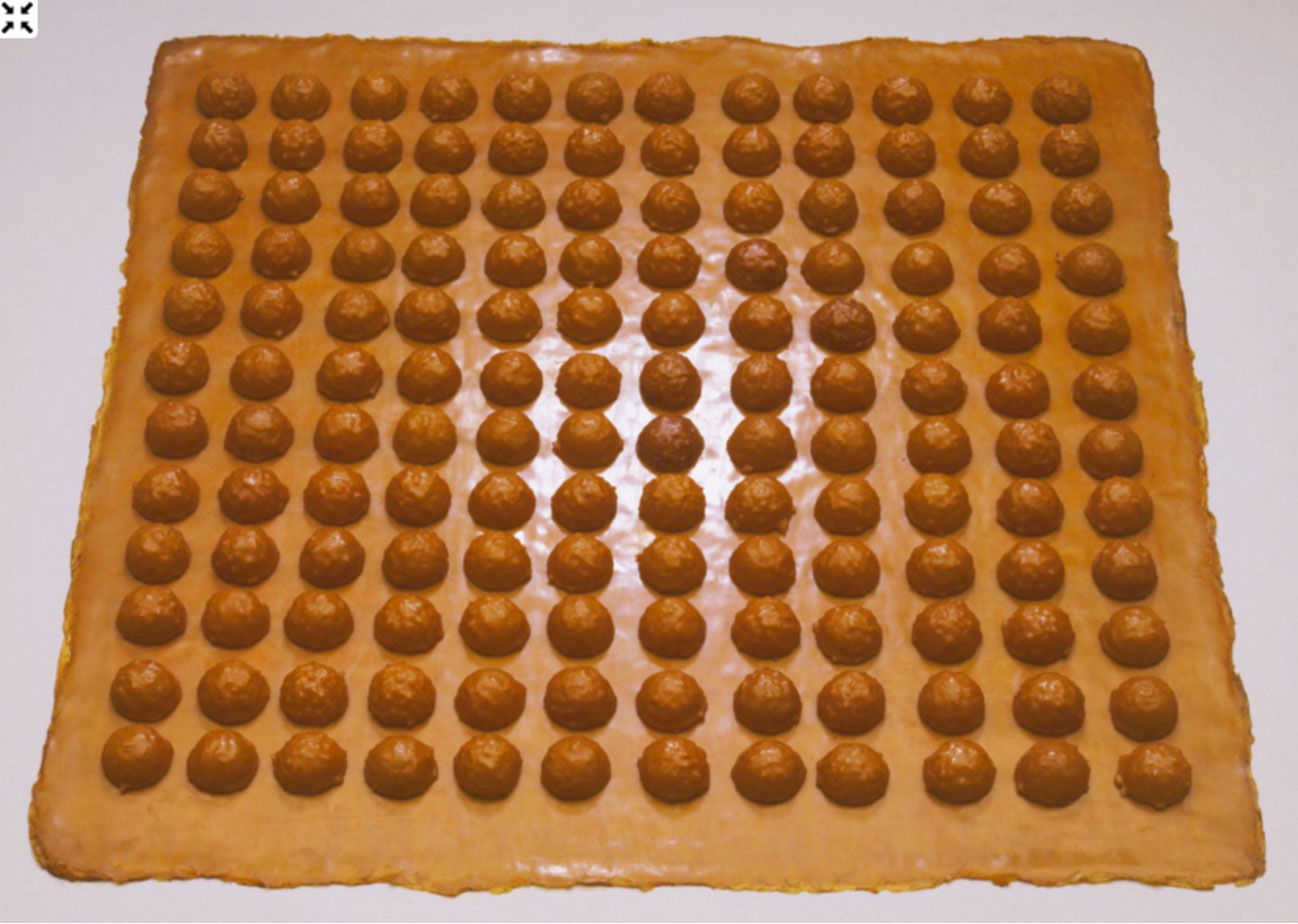

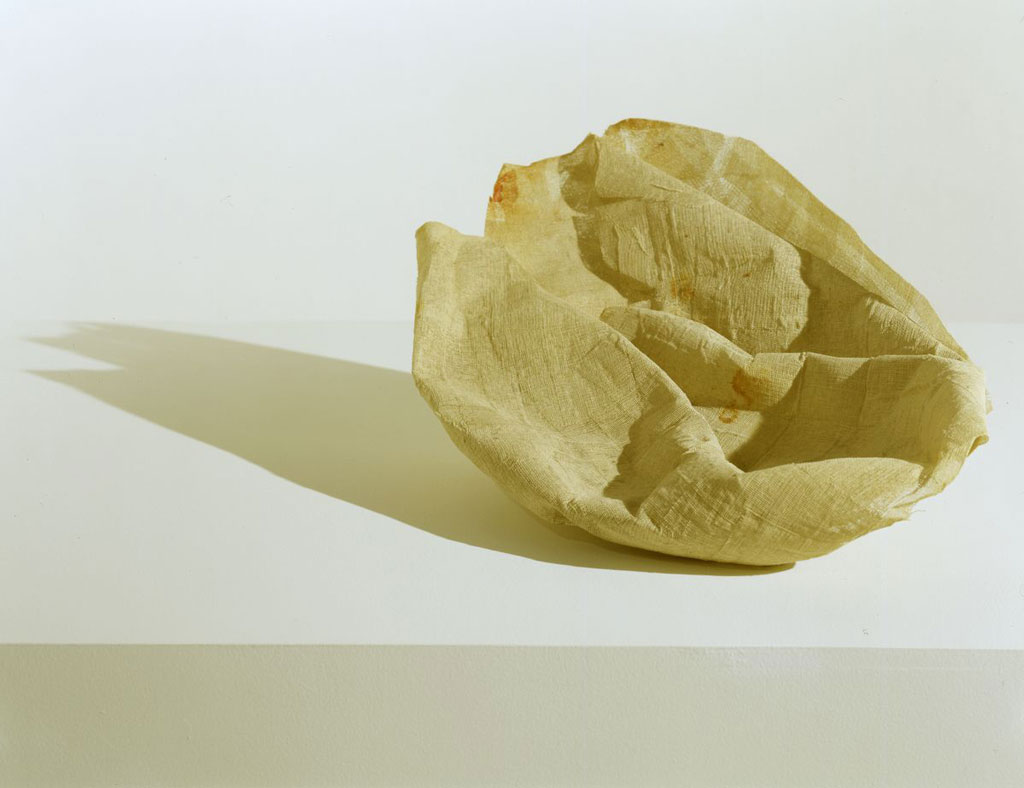

Eva Hesse was born on 11/1/1936, in Hamburg. Her family fled the Nazis and arrived in New York in 1939. She became a United States citizen in 1945. When Hesse was ten years old, her mother committed suicide. Racked with anxiety throughout most of her life, Hesse nonetheless persevered in her single-minded pursuit of making art. She attended the School of Industrial Art, then Pratt Institute in Brooklyn in 1952, and Cooper Union from 1954 to 1957. After winning a scholarship to the Yale Norfolk Summer School of Music and Art, Norfolk, Connecticut, in 1957, she was accepted by the School of Art and Architecture at Yale University, New Haven, where she studied painting with Josef Albers. In 1959, Hesse received her B.F.A. from Yale and returned to New York, where she worked as a textile designer. In 1961, Hesse exhibited drawings and watercolors for her first shows at John Heller Gallery, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Wadsworth Atheneum. In April of the same year, she met the sculptor Tom Doyle, whom she married six months later. She made her first 3-dimensional object (a costume made of chicken wire and soft jersey) for a Happening organized by Allan Kaprow, Walter De Maria, and others in 1962. Hesse had her first solo show, of drawings, the following year at the Allan Stone Gallery, New York. In 1964, she and Doyle spent over a year living in Kettwig-am-Ruhr, Germany, under the patronage of a German textile manufacturer and art collector. While in Europe, they traveled intermittently to Italy, France, and Switzerland. Hesse’s first solo show of sculpture was presented at the Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Düsseldorf, in 1965. She and Doyle returned to New York in 1965 and separated after several months. The year 1966 saw two landmark group shows in which she exhibited: “Stuffed Expressionism” at Graham Gallery, and “Eccentric Abstraction” curated by Lucy R. Lippard at Fischbach Gallery. Her work was singled out and critically praised in both shows. (1966 also saw the dissolution of her marriage to Doyle through separation.) The next year Hesse was given her first solo show at Fischbach, and was included in the Warehouse Show, “9 at Leo Castelli” along with fellow Yale alumnus Richard Serra. She was the only woman artist among the nine to be given the honor. Hesse began to use latex to make sculpture in 1967, and then fiberglass the following year. She started to gain recognition by the late 1960s, with solo shows at the Fischbach Gallery, New York, and inclusion in many important group exhibitions. While Hesse’s work shows affinities with the concerns of Minimalism, it cannot be easily characterized under any particular art movement. Hesse worked in a milieu of similarly-minded artists in New York, many of whom she called her friends. Nearest and dearest to her, however, was sculptor Sol LeWitt, who she called one of the two people “who really know and trust me”. The two artists equally exchanged influence and ideas, perhaps the most famous example of which is LeWitt’s letter to Hesse, encouraging her to quit distracting herself with insecurity and just “DO.” Months after her death, LeWitt dedicated the first of his famous wall drawings using “not straight” lines to his late friend. From 1968 to 1970, Hesse taught at the School of Visual Arts, New York. Her use of unconventional materials like latex has sometimes meant that her work is difficult to preserve. Hesse said that, just as “life doesn’t last, art doesn’t last.” Her art attempted to “dismantle the center” and destabilize the “life force” of existence, departing from the stability and predictability of minimalist sculpture. Her work was a deviation from the norm and as a result has had an indelible impact on sculpture today, which uses many of the looping and asymmetrical constructions that she pioneered. Hesse developed a brain tumor at the age of 33 and died in May 1970 at the age of 34. Though Hesse did not live to participate in it, the women’s movement of the 1970s championed her work as a female artist and ensured her lasting legacy as a pioneer in the American art world.

Eva Hesse was born on 11/1/1936, in Hamburg. Her family fled the Nazis and arrived in New York in 1939. She became a United States citizen in 1945. When Hesse was ten years old, her mother committed suicide. Racked with anxiety throughout most of her life, Hesse nonetheless persevered in her single-minded pursuit of making art. She attended the School of Industrial Art, then Pratt Institute in Brooklyn in 1952, and Cooper Union from 1954 to 1957. After winning a scholarship to the Yale Norfolk Summer School of Music and Art, Norfolk, Connecticut, in 1957, she was accepted by the School of Art and Architecture at Yale University, New Haven, where she studied painting with Josef Albers. In 1959, Hesse received her B.F.A. from Yale and returned to New York, where she worked as a textile designer. In 1961, Hesse exhibited drawings and watercolors for her first shows at John Heller Gallery, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Wadsworth Atheneum. In April of the same year, she met the sculptor Tom Doyle, whom she married six months later. She made her first 3-dimensional object (a costume made of chicken wire and soft jersey) for a Happening organized by Allan Kaprow, Walter De Maria, and others in 1962. Hesse had her first solo show, of drawings, the following year at the Allan Stone Gallery, New York. In 1964, she and Doyle spent over a year living in Kettwig-am-Ruhr, Germany, under the patronage of a German textile manufacturer and art collector. While in Europe, they traveled intermittently to Italy, France, and Switzerland. Hesse’s first solo show of sculpture was presented at the Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Düsseldorf, in 1965. She and Doyle returned to New York in 1965 and separated after several months. The year 1966 saw two landmark group shows in which she exhibited: “Stuffed Expressionism” at Graham Gallery, and “Eccentric Abstraction” curated by Lucy R. Lippard at Fischbach Gallery. Her work was singled out and critically praised in both shows. (1966 also saw the dissolution of her marriage to Doyle through separation.) The next year Hesse was given her first solo show at Fischbach, and was included in the Warehouse Show, “9 at Leo Castelli” along with fellow Yale alumnus Richard Serra. She was the only woman artist among the nine to be given the honor. Hesse began to use latex to make sculpture in 1967, and then fiberglass the following year. She started to gain recognition by the late 1960s, with solo shows at the Fischbach Gallery, New York, and inclusion in many important group exhibitions. While Hesse’s work shows affinities with the concerns of Minimalism, it cannot be easily characterized under any particular art movement. Hesse worked in a milieu of similarly-minded artists in New York, many of whom she called her friends. Nearest and dearest to her, however, was sculptor Sol LeWitt, who she called one of the two people “who really know and trust me”. The two artists equally exchanged influence and ideas, perhaps the most famous example of which is LeWitt’s letter to Hesse, encouraging her to quit distracting herself with insecurity and just “DO.” Months after her death, LeWitt dedicated the first of his famous wall drawings using “not straight” lines to his late friend. From 1968 to 1970, Hesse taught at the School of Visual Arts, New York. Her use of unconventional materials like latex has sometimes meant that her work is difficult to preserve. Hesse said that, just as “life doesn’t last, art doesn’t last.” Her art attempted to “dismantle the center” and destabilize the “life force” of existence, departing from the stability and predictability of minimalist sculpture. Her work was a deviation from the norm and as a result has had an indelible impact on sculpture today, which uses many of the looping and asymmetrical constructions that she pioneered. Hesse developed a brain tumor at the age of 33 and died in May 1970 at the age of 34. Though Hesse did not live to participate in it, the women’s movement of the 1970s championed her work as a female artist and ensured her lasting legacy as a pioneer in the American art world.