ART-Tribute:Great Realism,Great Abstraction

The drawing takes on a special role in the 20th Century. It has always been a medium of searching, inventing and experimenting. In the modern age, it also gained independence and autonomy and became – especially in times of state surveillance and oppression – a medium of free thought. In its diversity, it also reflects the complexity of the rapidly changing culture and society of the 20th Century.

The drawing takes on a special role in the 20th Century. It has always been a medium of searching, inventing and experimenting. In the modern age, it also gained independence and autonomy and became – especially in times of state surveillance and oppression – a medium of free thought. In its diversity, it also reflects the complexity of the rapidly changing culture and society of the 20th Century.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Städel Museum Archive

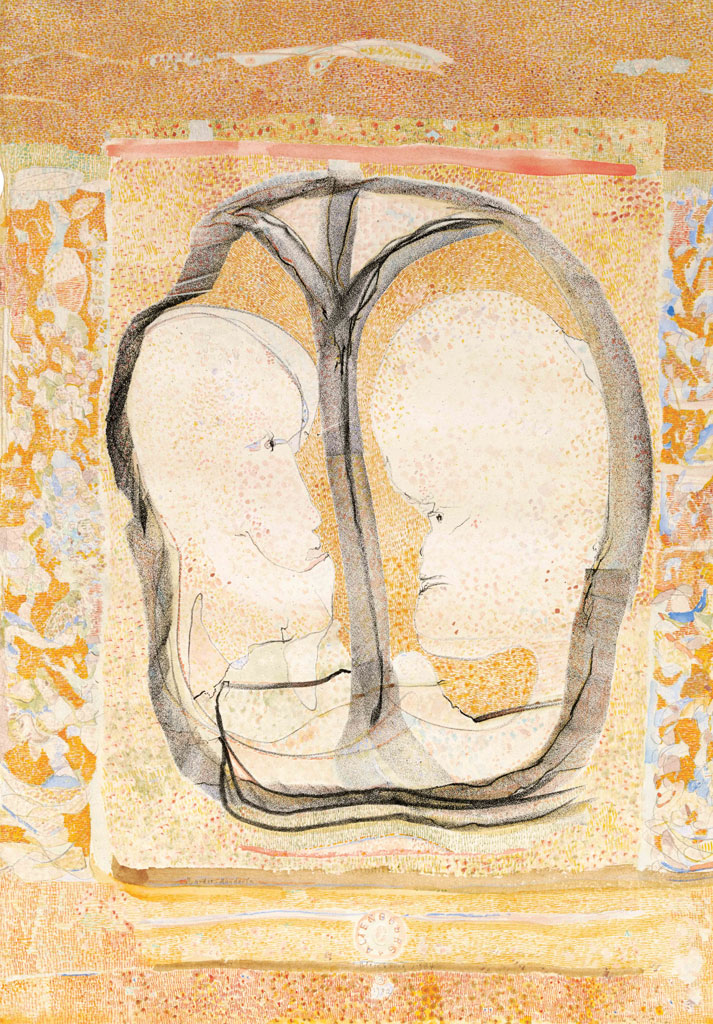

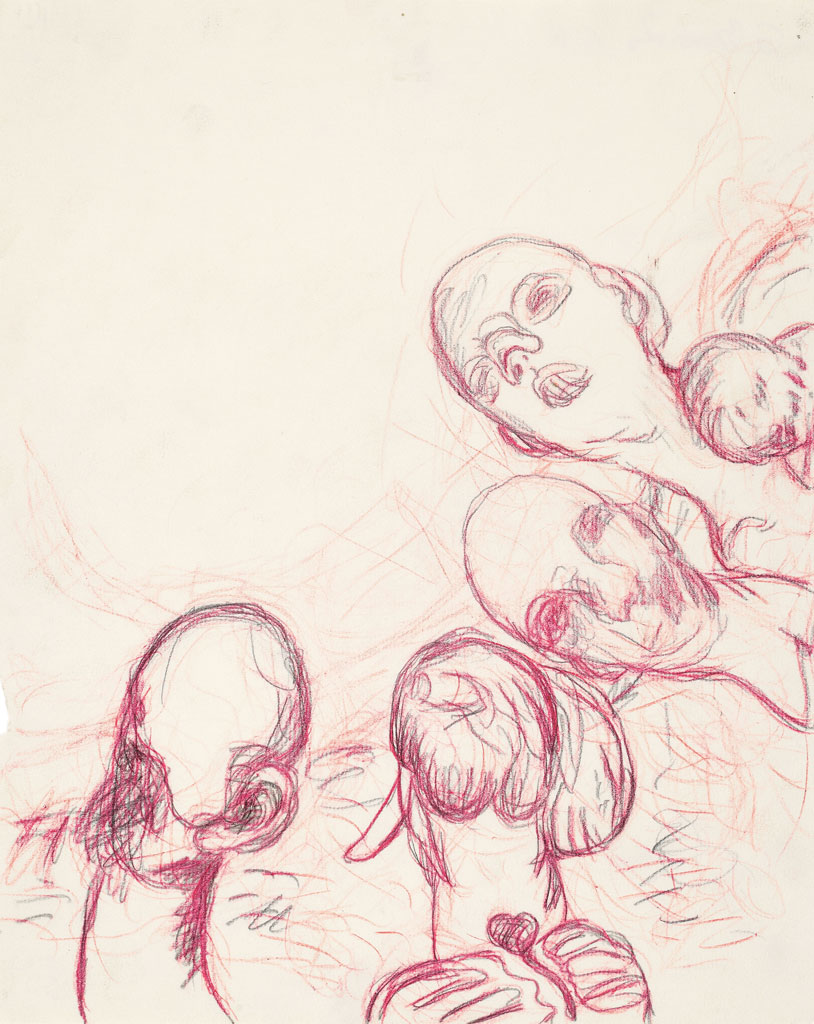

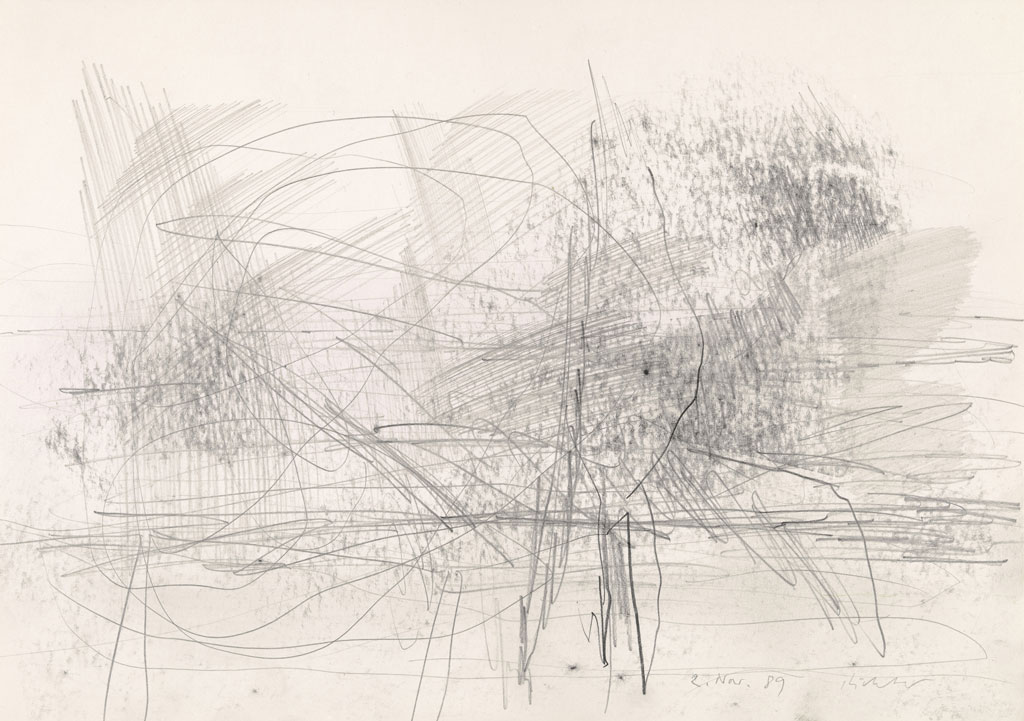

In the exhibition “Great Realism, Great Abstraction” the 100 works supplemented by 2paintings, are examined on the basis of various aspects, such as how the artists dealt with reality, how they questioned, further developed or undermined traditional pictorial ideas conveyed at the academies, and last but not least the fundamental significance of drawing within their respective oeuvres. The pencil sketches, brilliantly colorful pastels and aquarelles, and the monumental collages exhibited here also reveal the technical diversity of the medium of drawing, the specific characteristics of which the artists exploited, each in their own way. The drawings are loosely assigned to chronological groups which shed light in different ways on the relationship between closeness to the subject and abstract detachment from the model of nature. The Expressionists already used drawing as an autonomous art form, but at the same time it remained a medium of experimentation. Both are reflected in the first chapters of the exhibition dedicated to Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Max Beckmann. Shaken by the events of the WWI, Beckmann went to Frankfurt am Main in 1915 and initially withdrew to his private surroundings. He produced studies of the local environment as well as numerous portraits, including an intensive and personal pencil drawing of his close lady friend Fridel Battenberg from 1916 and a painterly pastel portrait of Marie Swarzenski from circa 1927. Marie Swarzenski was the wife of Georg Swarzenski, the then director of the Städelsches Kunstinstitut und Städtische Galerie, whom Beckmann captured shortly before his death in an impressive portrait, a charcoal drawing on blue paper, which can also be seen in the exhibition. These and other works illustrate Beckmann’s keen instinct for his vis-à-vis and the individual use of drawing utensils, and also document Beckmann’s changing formal language. The pre-war compositions are characterised by rounded lines and soft contours. The composition then became stricter, the motifs sharply outlined, revealing angular forms. For Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, drawing was the “key to his art”. One of the masterpieces is the pastel drawing “Berliner Straßenszene” (1914). The hasty glances of the two prostitutes depicted, their quick steps and those of the passers-by, define the image: Kirchner was fascinated by people in motion, by the hectic mood of the aspiring metropolis of Berlin, which he translated into striking lines. The reality of people’s lives was the source of his art. He abstracted what he saw by reducing natural forms to the essential. The close connection between man and nature linked Kirchner and Emil Nolde with each other, even after their time together in the artist group “Die Brücke”. In the 1920s and 1930s, a number of artists developed a strongly abstracted formal vocabulary, often following on from Expressionism. They also turned away from traditional compositional principles taught at the academies and initially tested new means of representation on paper. They abandoned naturalistic depictions and transformed what they had seen and experienced into fundamental pictorial elements such as line and surface, color and form. Rolf Nesch, Werner Gilles and Ernst Wilhelm Nay worked with two-dimensional colour forms, striking lines and geometric figural depictions and dispensed with an illusionistic representation of depth. Baumeister into relief-like surface structures reminiscent of rock formations. Two drawings by Paul Klee, who had travelled to Tunisia with August Macke and had been inspired by his impressions on this journey to increasingly abstract compositions, reflect his virtuosity and joy of experimentation in drawing. Against the background of the atrocities of National Socialism and the WW II, it seemed impossible for many young artists around 1945/50 to continue the art of the 1920s and 1930s. Like the generations before and after the WW I, they were searching for new forms of expression. They developed an abstract pictorial language based exclusively on color and form, which placed the expressive gesture at the centre of their art: Proceeding from early Tachist tendencies in France and influenced by Surrealism, Art Informel developed in Germany. At the beginning of the 1950s, Frankfurt am Main became the German centre of this new movement. Karl Otto Götz first visited the city in 1950 and met the like-minded artists Otto Greis, Bernard Schultze and Heinz Kreutz. In December 1952, they formed the loose artist group “Quadriga”. Götz drew quickly and developed a painting style based on movement. He covered his paintings with dynamic swirls and swaths of color, as in the untitled gouache from 1957. For this, he used a new technique, discovered rather by chance in the summer of 1952, in which he applied paint to paper and spread it across the surface with a knife or squeegee. In this way, he succeeded in dissolving formal elements. The many varieties of Art Informel can be seen in the exhibition: delicate bundles of lines in graphite, as well as color-intensive splashes and dabs of paint, fine nets of lines and paste-like paint spreading into the third dimension. Many artists of the post-war generation also clearly distinguished themselves from the representatives of Art Informel. As children, they had experienced the horrors and consequences of the Second World War and now made recent German history their theme. To this end, they explicitly resorted to a figurative visual language. Eugen Schönebeck and Georg Baselitz depicted deformed bodies covered with scars, wounds and ulcers in their colored pencil and ink drawings. In the 1960s, German artists not only began to focus more on their own recent past, but also on the bourgeois, consumer-oriented affluent society. In his drawings, Thomas Bayrle clothed a female nude with a coat, the pattern of which is composed of coffee cups. In addition, everyday drawing utensils previously deemed unworthy of art or newly developed, such as ballpoint, neon and fineliner pens, as well as spray paints were used. Sigmar Polke used them both for simple drawings as well as for complex collages. Many artists exceeded the usual formats of drawing and created monumental works: Antonius Höckelmann (1937–2000) stretched a network of winding loops over broad strips of paper, and Johannes Grützke staged his own person in large-format self-portraits. Peter Sorge reflected the changing media landscape and the increasing omnipresence of images in his colored pencil drawings composed of various pictorial quotations, which are more topical than ever today.

Info: Curator: Jenny Graser, Städel Museum, Schaumainkai 63, Frankfurt am Main, Duration: 13/11/19-16/2/20, Days & Hours: Tue-Wed & Sat-Sun 10:00-19:00, Thu-Fri 10:00-21:00, www.staedelmuseum.de