ART CITIES:N.York-Sur Moderno,Journeys of Abstraction

In the years after the WWII, South American Avant-Garde groups sought to reinvent abstract art, creating scores of manifestos, journals, and exhibitions. Artists from Montevideo, Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Caracas built upon the legacies of European abstraction, transforming them in order to produce one of the most vibrant and radical chapters in the history of South American modernism.

In the years after the WWII, South American Avant-Garde groups sought to reinvent abstract art, creating scores of manifestos, journals, and exhibitions. Artists from Montevideo, Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Caracas built upon the legacies of European abstraction, transforming them in order to produce one of the most vibrant and radical chapters in the history of South American modernism.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: MoMA Archive

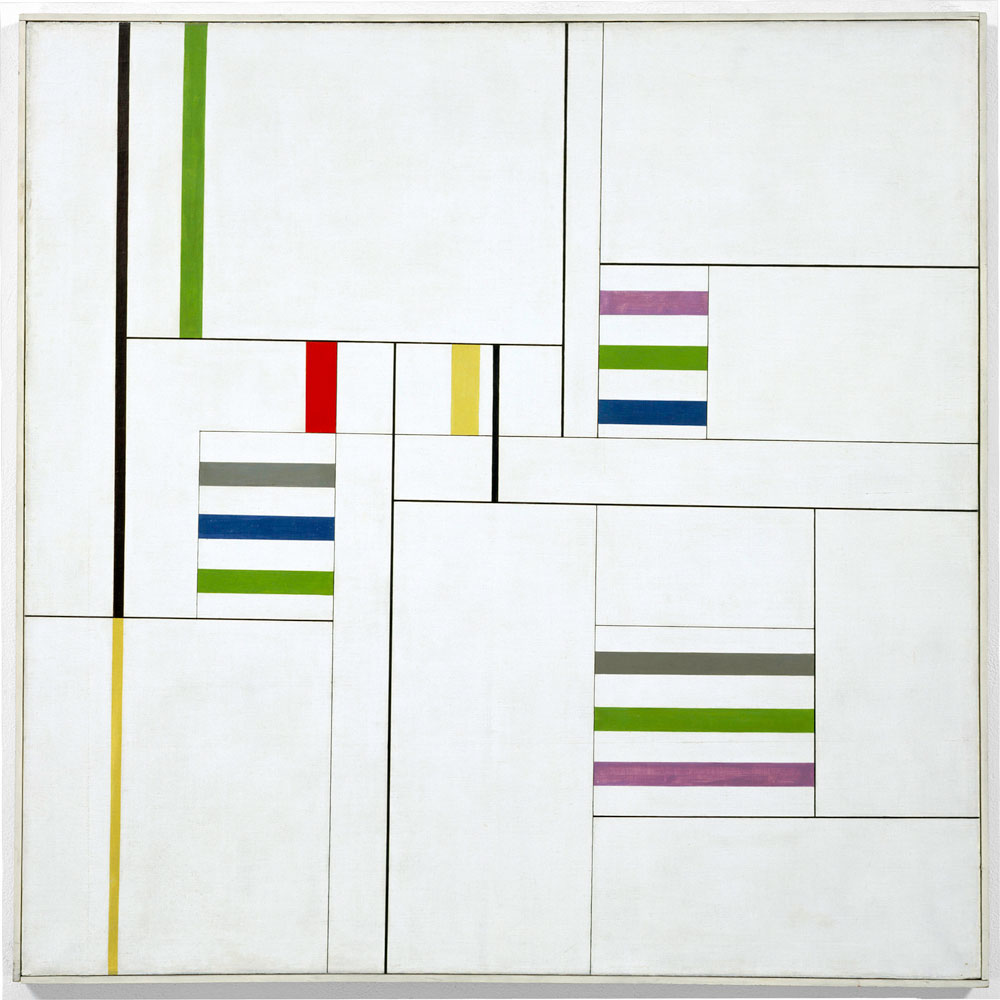

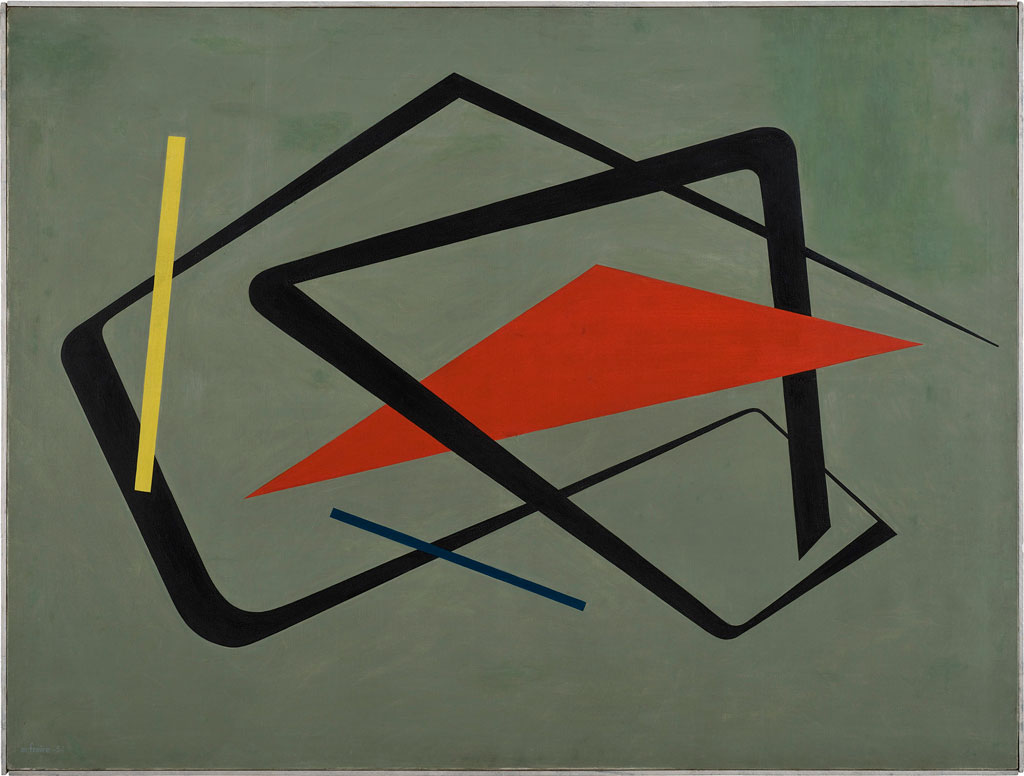

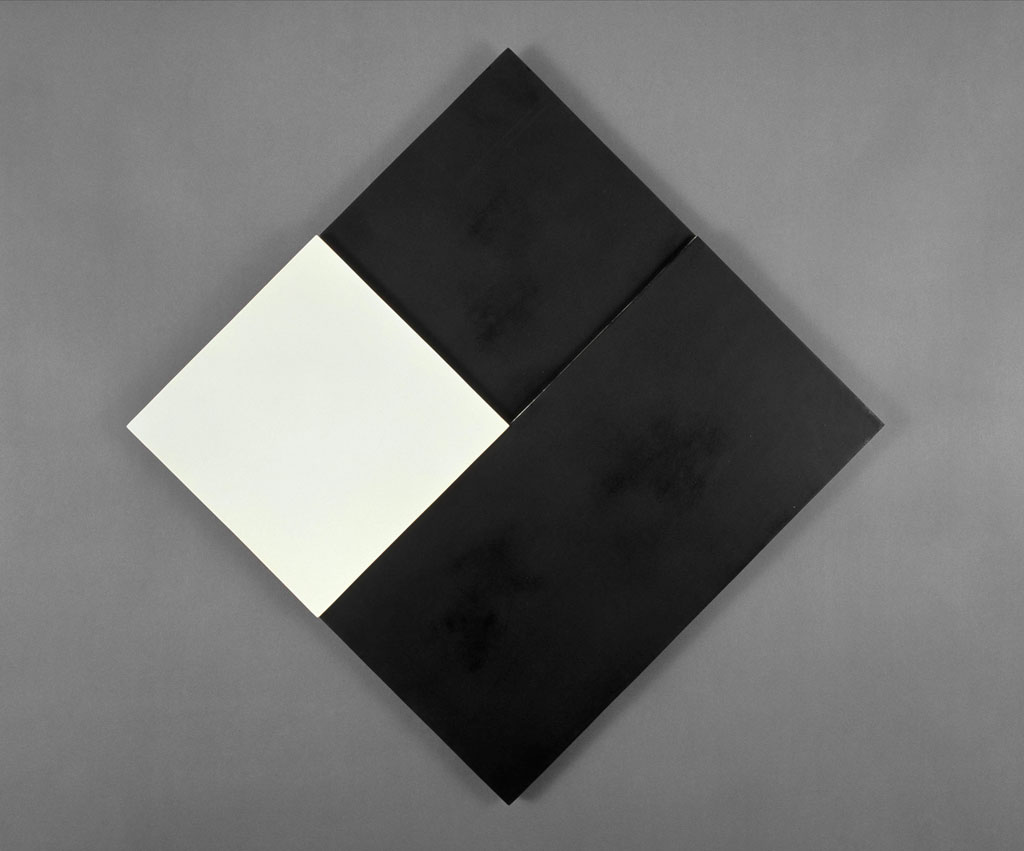

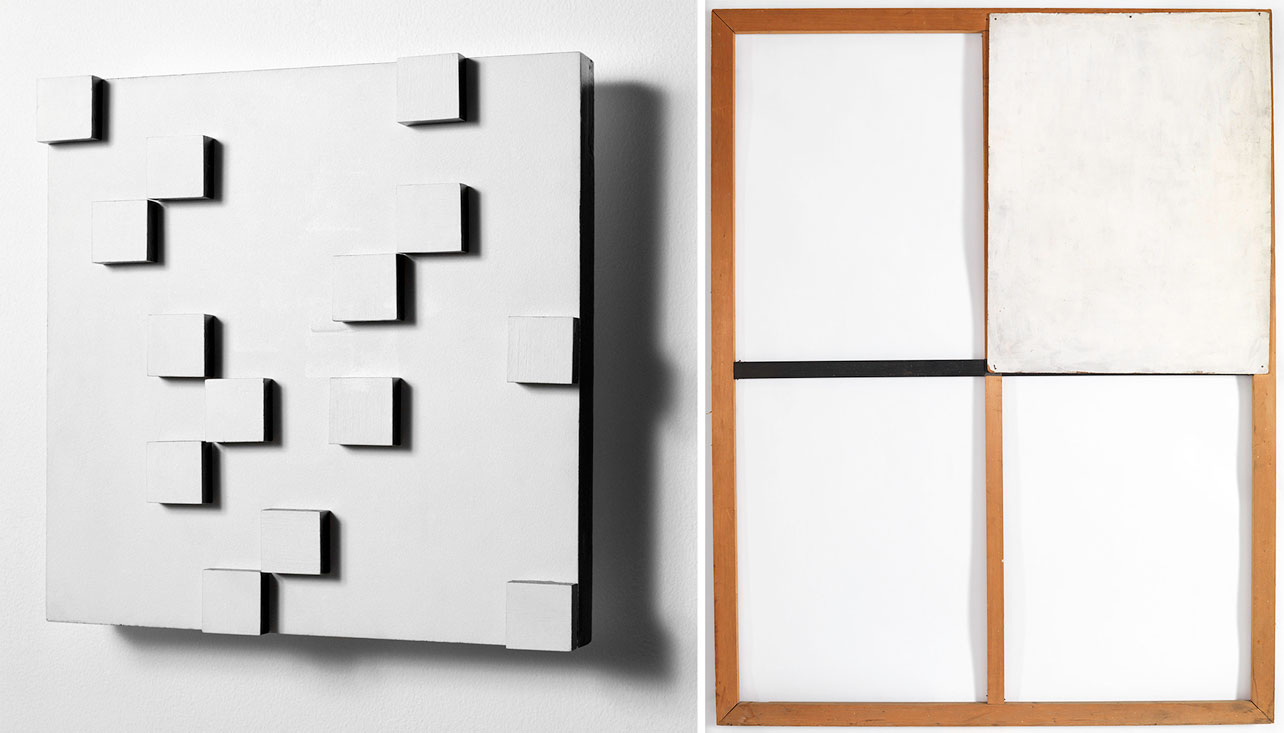

The exhibition “Sur moderno: Journeys of Abstraction-The Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Gift” celebrates the arrival of the most important Collection of abstract and concrete art from Latin America by dedicating an entire suite of galleries on MoMA’s third floor to the display of artists from Brazil, Venezuela, Argentina, and Uruguay. The exhibition highlights the work of Lygia Clark, Gego, Raúl Lozza, Hélio Oiticica, Jesús Rafael Soto, and Rhod Rothfuss, among others, focusing on the concept of transformation: a radical reinvention of the art object and a renewal of the social environment through art and design. The exhibition is also anchored by a selection of archival materials that situate the works within their local contexts. The exhibition is divided into two main sections based on the concept of transformation. The first section, “Artworks as Artifacts, Artworks as Manifestos” presents a group of works that subverted the conventional formats of painting and sculpture. Cuts, folds, articulated objects, cut-out frames, and experiments that question the autonomy of the art object are some examples of these artists’ material explorations. The works in the sub-section “Cuts and folds” have been cut, folded, or extended into three dimensions. When first exhibited, some of them lacked the frames and pedestals that usually separate art from everyday objects, and viewers could manipulate them. In some cases, artists deliberately brought attention to the volume of the works by painting their edges. These artists radically reconfigured the relationship viewers have to art by staging an increasingly corporeal and interactive encounter. Most of the works in this section were produced by Brazilian Neo-Concrete artists, who wanted their art to appeal to the mind as well as the senses. In this, they were reacting against the tradition of Concrete art, in which geometry was used to construct images that followed a strictly visual and conceptual logic. The artworks gathered in “Unsteady optics” appear to vibrate or change colors as the viewer moves in front of them. Leading Venezuelan and Brazilian artists of the 1950s explored scientific methodologies to create these fleeting optical effects: they experimented with transparent materials, superimposed patterns, and lenticular constructions. The artist Jesús Rafael Soto recounted, “I discovered a phenomenon that left me floating on air for almost a week: when I superimposed plots [of dots], luminous nuclei appeared, rotating and moving whenever I shifted position in front of them”. Other artists created works suggestive of movement by studying the mechanics of human vision as well as its recognition of patterns and forms. “A revolution of limits”: A constellation of artists working in Buenos Aires and Montevideo in the mid-1940s made a daring proposal to abandon one of painting’s most enduring conventions: the rectangular frame. Rhod Rothfuss, the Uruguayan artist who first wrote about this idea, argued that the internal composition of a painting should determine the shape of its borders. These artists (most of whom aligned themselves with the Communist Party) believed that their artistic innovations could transform social consciousness by opposing traditional (or bourgeois) art forms.The exhibition’s inclusion of “Spatial Construction no. 12” (c. 1920) by Aleksandr Rodchenko highlights the influence of Russian Constructivism on South American art. Similarly, images of Piet Mondrian’s works were widely circulated and had a great impact on the development of abstraction in the region. His “Broadway Boogie Woogie” (1942-43), on view in the exhibition, inspired investigations of kineticism among artists such as Jesús Rafael Soto, whose “Double Transparency” (1956) is an attempt to transform the two-dimensionality of Mondrian’s painting into a three-dimensional experience. In the second section, “Modern as Abstract” the language of abstraction is displayed as both a product of and a catalyst for the transformation of the artists’ surroundings. The geometrical principles of abstract painting carried over into the everyday, where artists and architects recognized one another as allies, leading to a shared operation and set of ideals. The section “A modern worldview” of the exhibition displays artworks alongside examples of furniture, textile, and graphic design that demonstrate the ways in which, starting in the mid-1950s, the language of abstraction became synonymous with modernity in South America, spilling over from artworks into the everyday to tablecloths, chairs, and even cities. At this time, artists, designers, and architects in the region recognized one another as allies sharing not just a visual language but ideals as well. This so-called “synthesis of the arts” was a project of cross-disciplinary integration that crystallized in two paradigmatic projects, the Ciudad Universitaria, in Caracas, and Brazil’s new capital, Brasília. Here, María Freire’s “Untitled” (1954), for example, is displayed alongside archival materials and works from MoMA’s Architecture and Design Collection, in an exploration of public sculptural projects and furniture design. “Shaking up the grid”: Many South American artists used the image of the grid— a long-standing metaphor for progress, stability, and order—only to make it elastic, messy, and fragile. By doing so, they explored its contradictions and even questioned the benefits of modernization. Thinking about the use of the grid in his art of the 1970s, the Venezuelan artist Eugenio Espinoza wrote, “I saw the grid everywhere. Order is an interesting social imposition. I didn’t want to control my impulses, my anxiety. My work has been determined by a historical order and an emotional chaos”. Gego’s “Square Reticularea 71/6” (1971) and Hélio Oiticica’s “Painting 9” (1959) areexamples of works in the exhibition that approached the transformation and expansion of the rational grid in different ways. Oiticica disrupted the strict geometric system with his rhythmically arranged rectangles, while Gego warps and deconstructs the reticular structure.

Info: Curators: Inés Katzenstein and María Amalia García, Curatorial Assistant Karen Grimson, MoMA, 11 West 53 Street, Manhattan, New York, Duration: 21/10/19-14/3/20, Days & Hours: Mon-Thu & Sat-Sun 10:00-17:30, Fri 10:00-21:00, www.moma.org