ART-PRESENTATION: Nam June Paik

Nam June Paik internationally recognized as the “Father of Video Art,” created a large body of work including video sculptures, installations, performances, videotapes and television productions. Nam June Paik challenged and changed our understanding of visual culture. His collaborative and interdisciplinary practice foresaw the importance of mass media and new technologies, coining the phrase “electronic superhighway” to predict the future of communication in an internet age. He has become synonymous with the electronic image through a prodigious output of manipulated TV sets, live performances, global television broadcasts, single-channel videos, and video installations.

Nam June Paik internationally recognized as the “Father of Video Art,” created a large body of work including video sculptures, installations, performances, videotapes and television productions. Nam June Paik challenged and changed our understanding of visual culture. His collaborative and interdisciplinary practice foresaw the importance of mass media and new technologies, coining the phrase “electronic superhighway” to predict the future of communication in an internet age. He has become synonymous with the electronic image through a prodigious output of manipulated TV sets, live performances, global television broadcasts, single-channel videos, and video installations.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Tate Archive

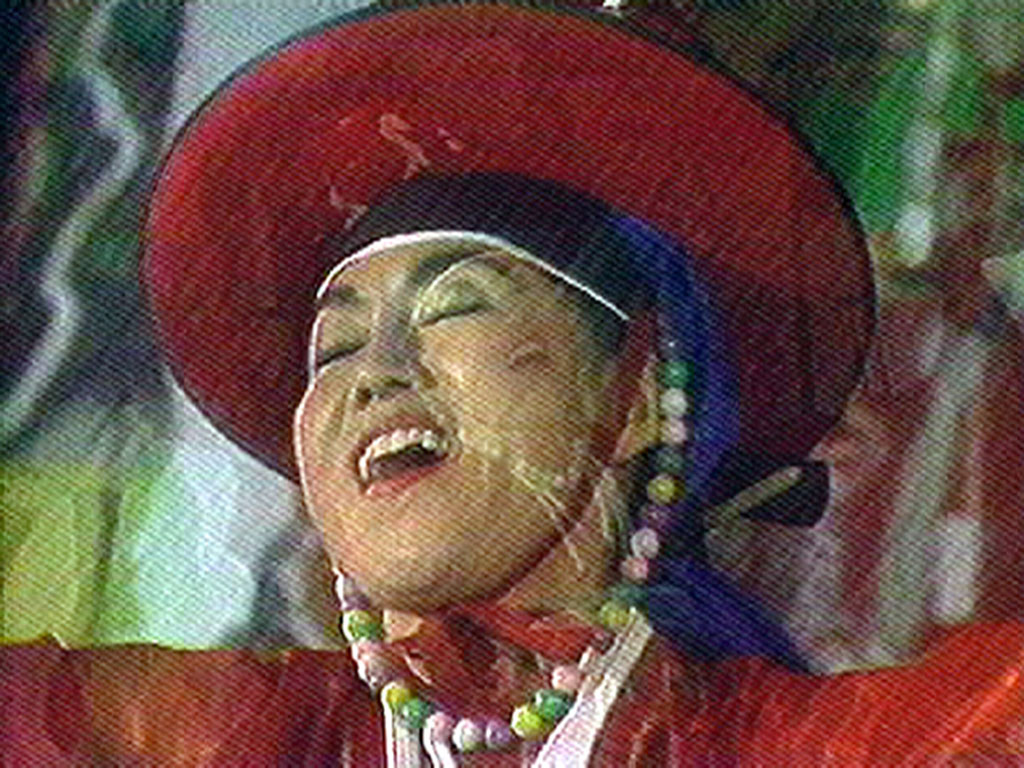

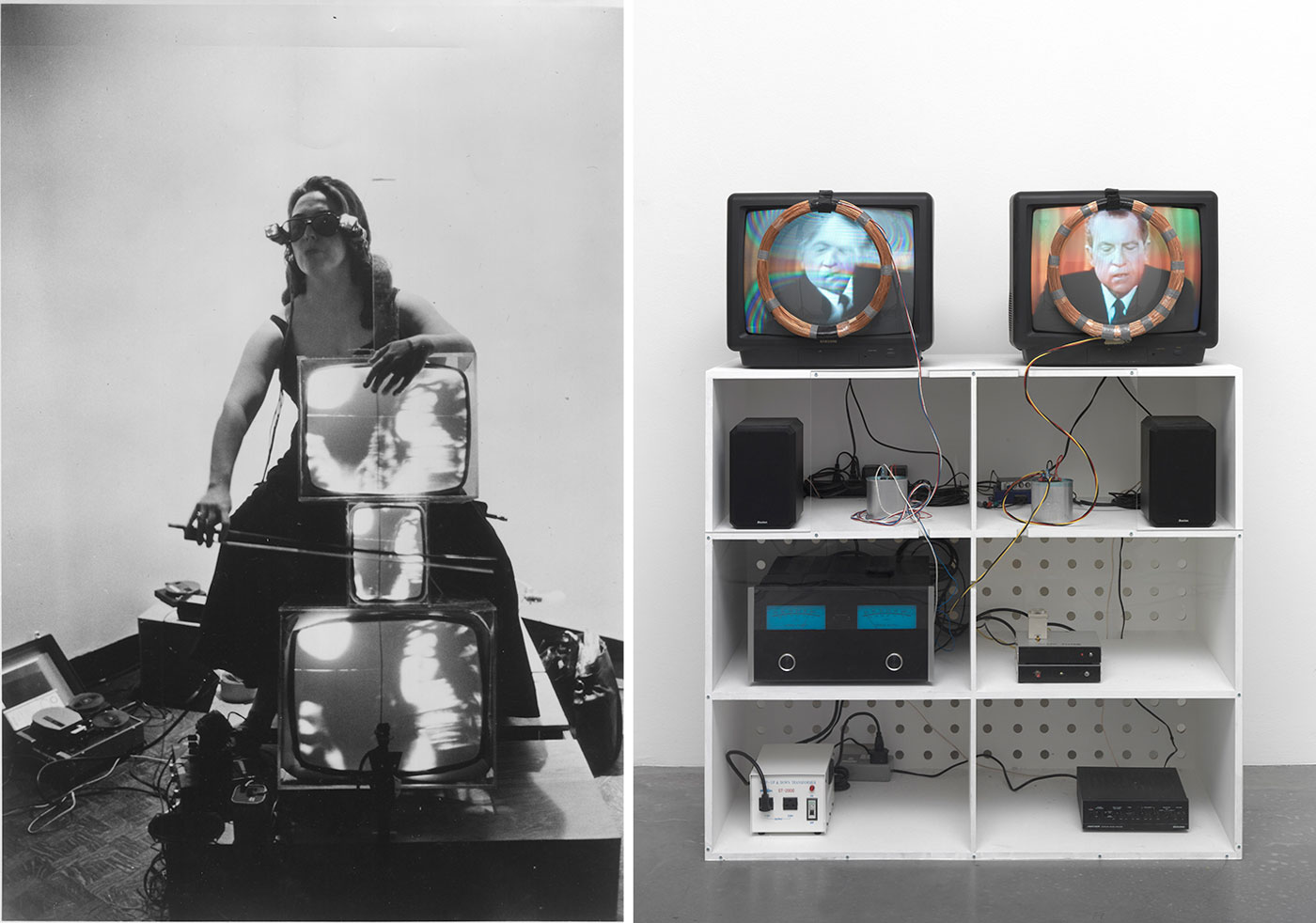

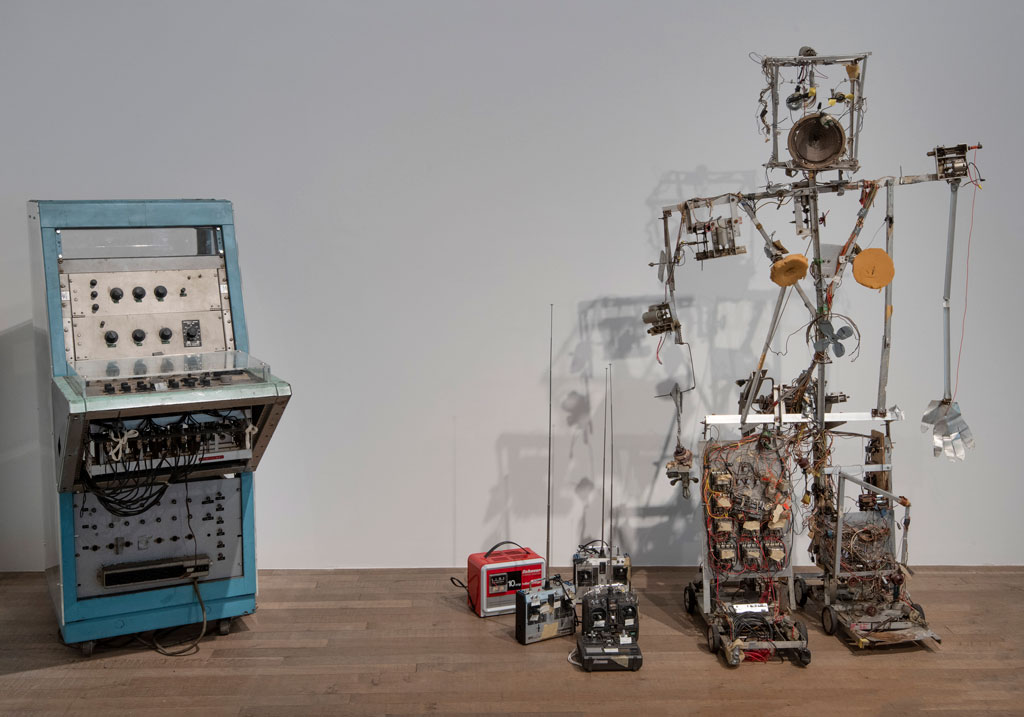

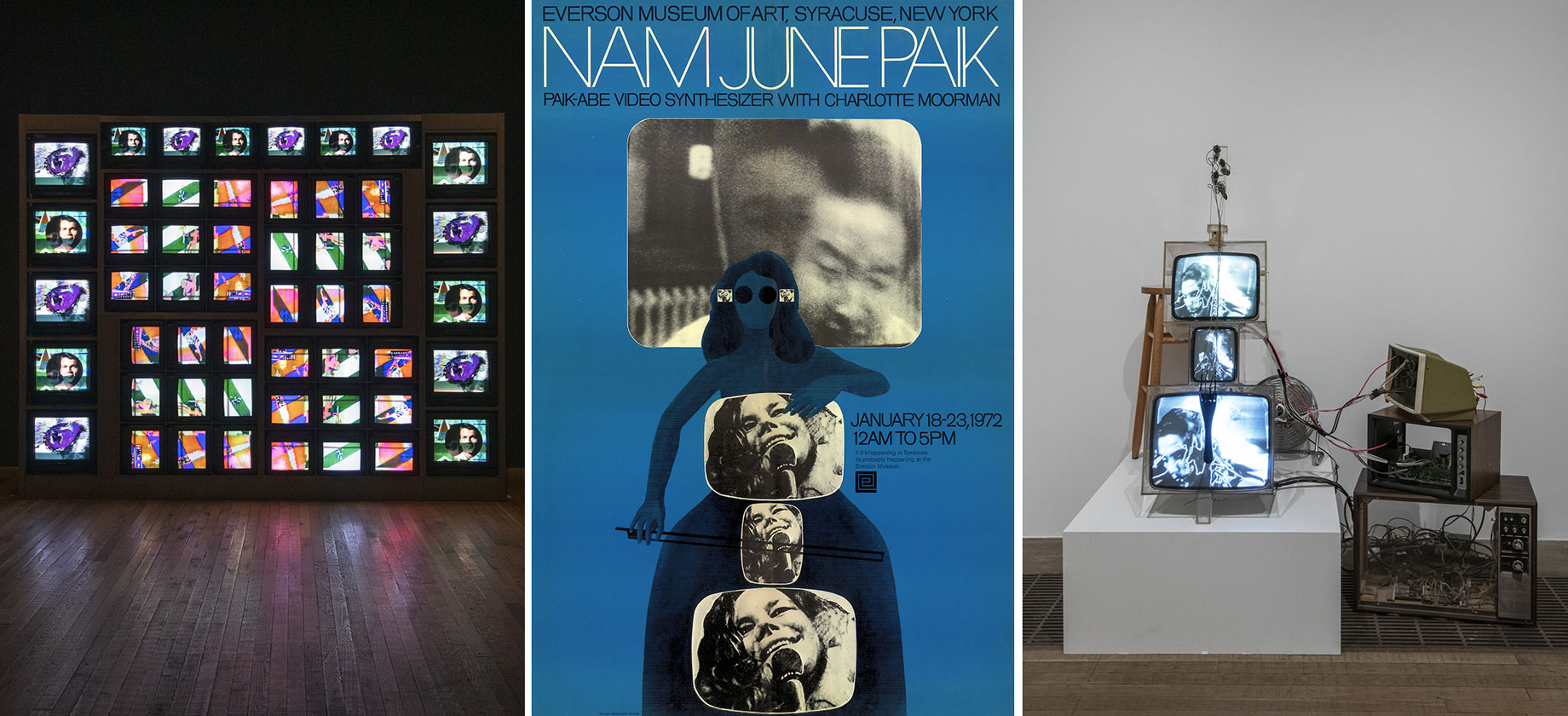

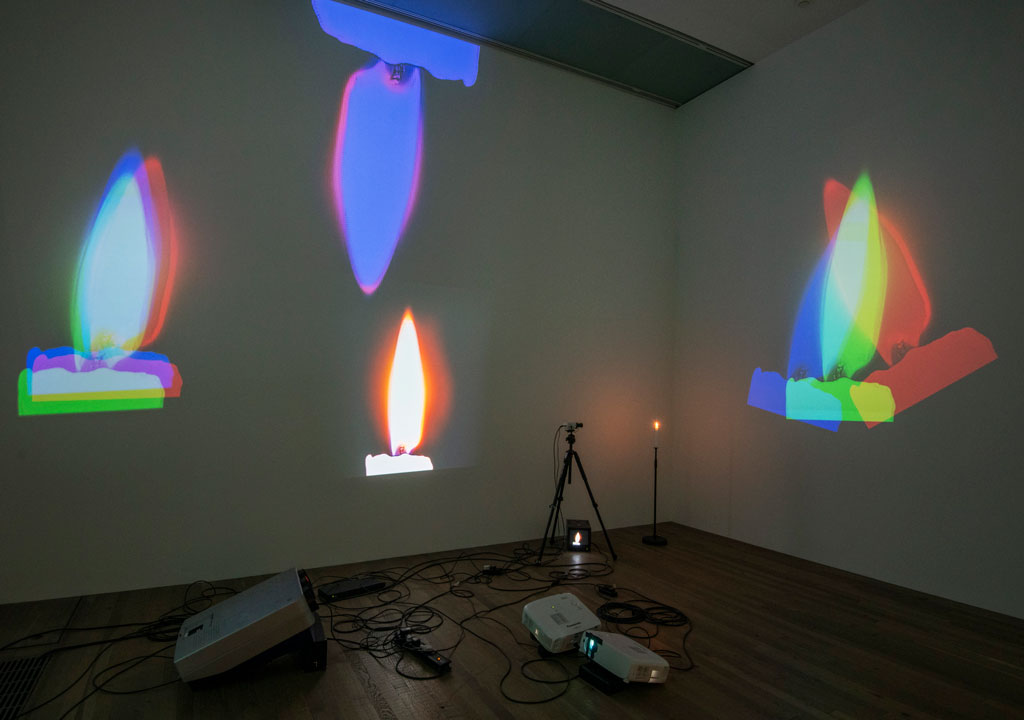

Over 200 artworks, photographs, films and archive objects by Nam June Paik are brought together in the major exhibition at Tate Modern. Nam June Paik has become synonymous with the electronic image through a prodigious output of manipulated TV sets, live performances, global television broadcasts, single-channel videos, and video installations. To introduce Paik’s radical world, the exhibition opens with “TV Garden” (1974/2002), this large-scale installation explores diminishing distinctions between nature and technology, comprising dozens of television sets that appear to grow from within a garden of lush foliage. Paik’s first robot work “Robot K-456” (1964) is also on display and a room is dedicated to screening three of Paik’s ground-breaking satellite videos. Broadcast throughout the 1980s, these ambitious works feature icons of popular culture including Peter Gabriel, Laurie Anderson, David Bowie and Lou Reed, defining the MTV aesthetic of the era. Nam June Paik’s very first robot sculpture “Robot K-456” is made from intentionally low-fi materials including wire, wood and foam, the rickety figure was designed in collaboration with Japanese electronic engineer Shuya Abe. At a time when many advances were being developed for military purposes, Paik sought to reflect technology’s growing importance in everyday life and to reclaim these innovations as symbols of fun and peace. He hoped to make technology more approachable by recreating human-like features, so they no longer seemed to be the product of complex and hidden scientific processes. He said of the playful work, “I thought it should meet people in the street and give them a split-second surprise”. Originally a remote control “mechanical performer”, “Robot K-456” was capable of walking, raising its arms, playing recorded sounds and even urinating. The robot became a central element of several of Paik’s performances, illustrated in the exhibition by extraordinary archive photography. The artist continued to create robots throughout his life, including the series “Family of Robot” which was constructed from radio cabinets and TV sets. Tate Modern has brought together Aunt 1986 and Uncle 1986 from this group, on rare loan from private collections. The artist also played a pivotal role in Fluxus, an international network of avant-garde artists, composers, designers and poets, through the cross-germination of radical aesthetics and experimentation. Born in South Korea, but living and working in Japan, Germany and the USA, Paik collaborated with a global community of cutting-edge artists. The show highlights key creative partnerships with composer John Cage, choreographer Merce Cunningham and artist Joseph Beuys. Paik’s collaboration with cellist Charlotte Moorman was also deeply significant for both artists, who developed a repertoire of provocative performances incorporating Paik’s TV sculptures within elaborate costumes and props. “Room for Charlotte Moorman” (1993) was created by Paik following Moorman’s death in 1991. The poignant installation features Moorman’s clothing and handbag and is shown alongside props, costumes, videos and photography from their nearly 30-year creative partnership. Moorman was renowned as a radical cellist and avant-garde artist whose work was characterised by improvised, visceral and daring performances. Fearless and often provocative, the Julliard-trained musician would regularly perform in various degrees of undress and during one event in New York in 1967 the stage was stormed by police who arrested her for public indecency. The New York Times consequently dubbed her “The Topless Cellist” and the ensuing proceedings put the question of the artistic merits of eroticism on trial. Paik and Moorman responded to the controversy by conceiving a series of television sculptures, “TV Bra for Living Sculpture” 1969, “TV Cello” and “TV Eyeglasses” (both 1971)which were worn and played by Moorman during performances. Tate Modern has restaged Nam June Paik’s “Sistine Chapel” for the first time since its creation over 25 years ago. The work was originally unveiled as part of the Golden Lion winning German Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1993 and has never been reconstructed since. Created with 34 projectors, the immersive full-room installation presents a kaleidoscopic audio-visual collage. It features many of Paik’s friends and collaborators alongside other public figures, including John Cage, David Bowie and Janis Joplin. Nam June Paik and Hans Haacke were jointly invited to represent Germany at the Biennale in 1993. Paik took inspiration from Marco Polo’s 13th Century journey from Venice to Mongolia, China and beyond, reflecting on his own experiences as a Korean-born artist in the west and the philosophical links between Europe and Asia. He showed “Sistine Chapel” alongside works like “The Mongolian Tent” (1993) which also receives its UK debut. A room is devoted to Paik’s pivotal first solo exhibition, “Exposition of Music – Electronic Television Staged in Wuppertal, Germany in 1963, the landmark show filled three storeys of the gallery with immersive environments and sculptures that invited the active participation of the audience. It was an ambitious debut for the artist’s early experiments with manipulated television sets. Paik was one of the first to recognise the potential of TV and video as an artistic medium, exploring and expanding the limits of their intended purpose. On display at Tate Modern, “Foot Switch Experiment” (1963) allows audiences to alter a picture on screen in real time by triggering a switch. In contrast, “Zen for TV” (1963) presents a TV lying on its side with the image compressed to a single, tranquil column of light, reflecting the importance Zen, Taoism and wider Buddhist philosophies in Paik’s approach to art and technology. The exhibition also showcased an array of musical instruments made or modified by the artist, including “Zen for Wind” (1963), consisting of a medley of dangling objects originally playing random noises as they move and rattle. A recreation of “Random Access” (1963) also allows visitors to experiment with sound, activating haphazard lines of magnetic tape attached to the wall.

Info: Curators: Sook-Kyung Lee, Rudolf Frieling, Valentina Ravaglia and Michael Raymond, Tate Modern, Bankside, London, Duration: 17/10/19-9/2/20, Days & Hours: Mon-Thu & Sun 10:00-18:00, Fri-Sat 10:00-22:00, www.tate.org.uk