ART-PRESENTATION: Pop América 1965-1975

Despite the wide appeal of Pop Art’s engaging imagery, the broader public remains unaware of the participation and significant contribution of Latin American and Latino/a artists working at the same time and alongside their U.S. and European counterparts. “Pop América, 1965-1975” is the first exhibition with a hemispheric vision of Pop. The exhibition makes a timely and critical contribution to a more complete understanding of this artistic period.

Despite the wide appeal of Pop Art’s engaging imagery, the broader public remains unaware of the participation and significant contribution of Latin American and Latino/a artists working at the same time and alongside their U.S. and European counterparts. “Pop América, 1965-1975” is the first exhibition with a hemispheric vision of Pop. The exhibition makes a timely and critical contribution to a more complete understanding of this artistic period.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Block Museum of Art Archive

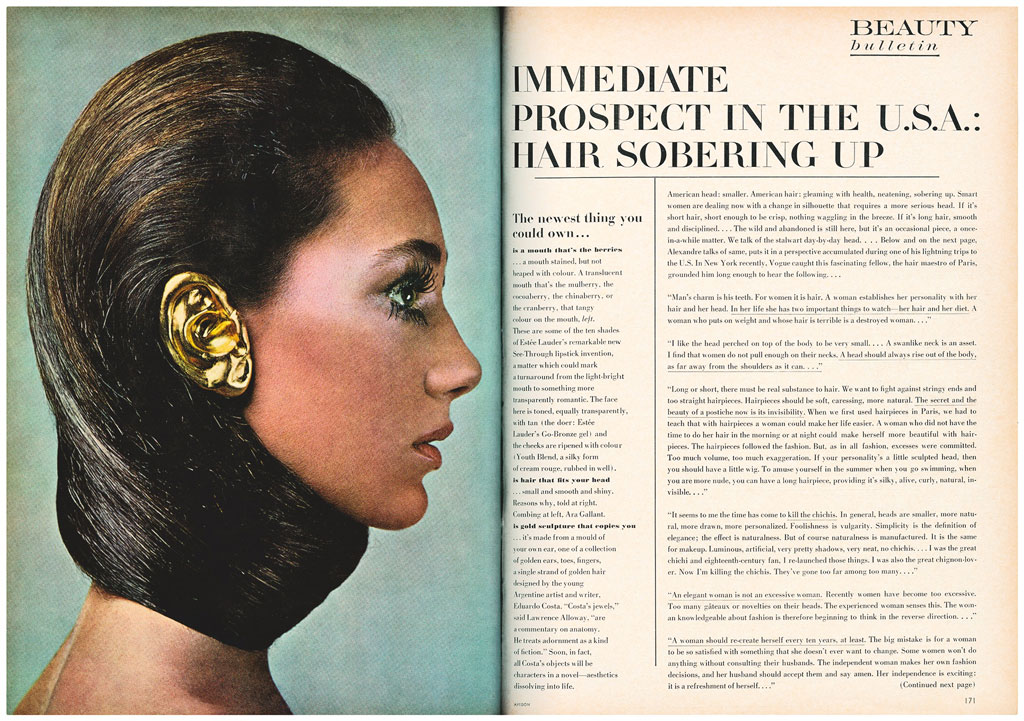

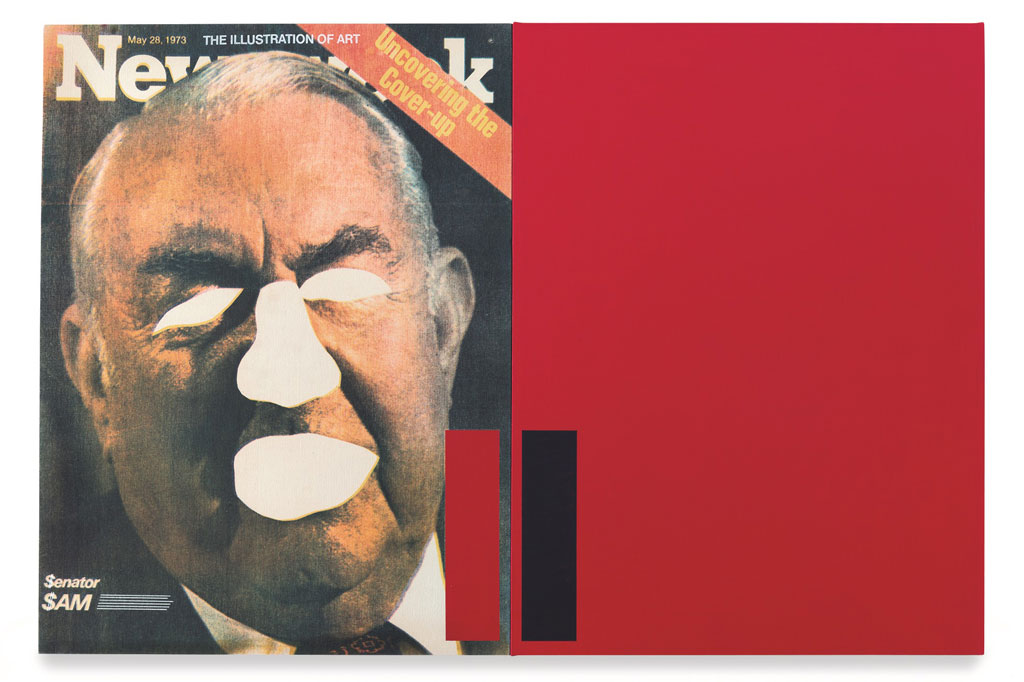

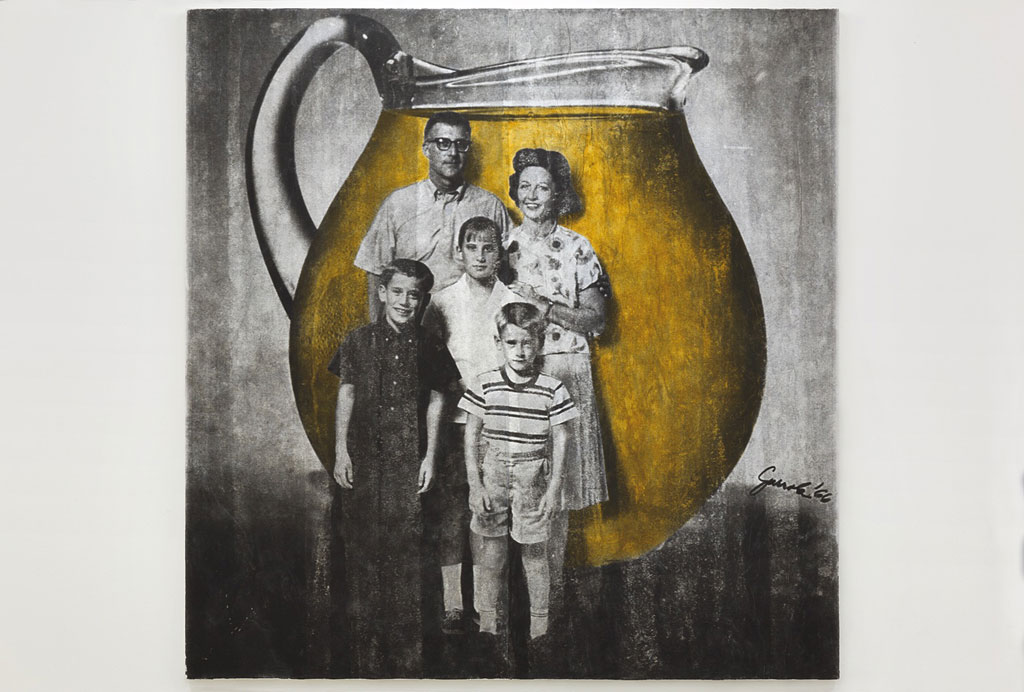

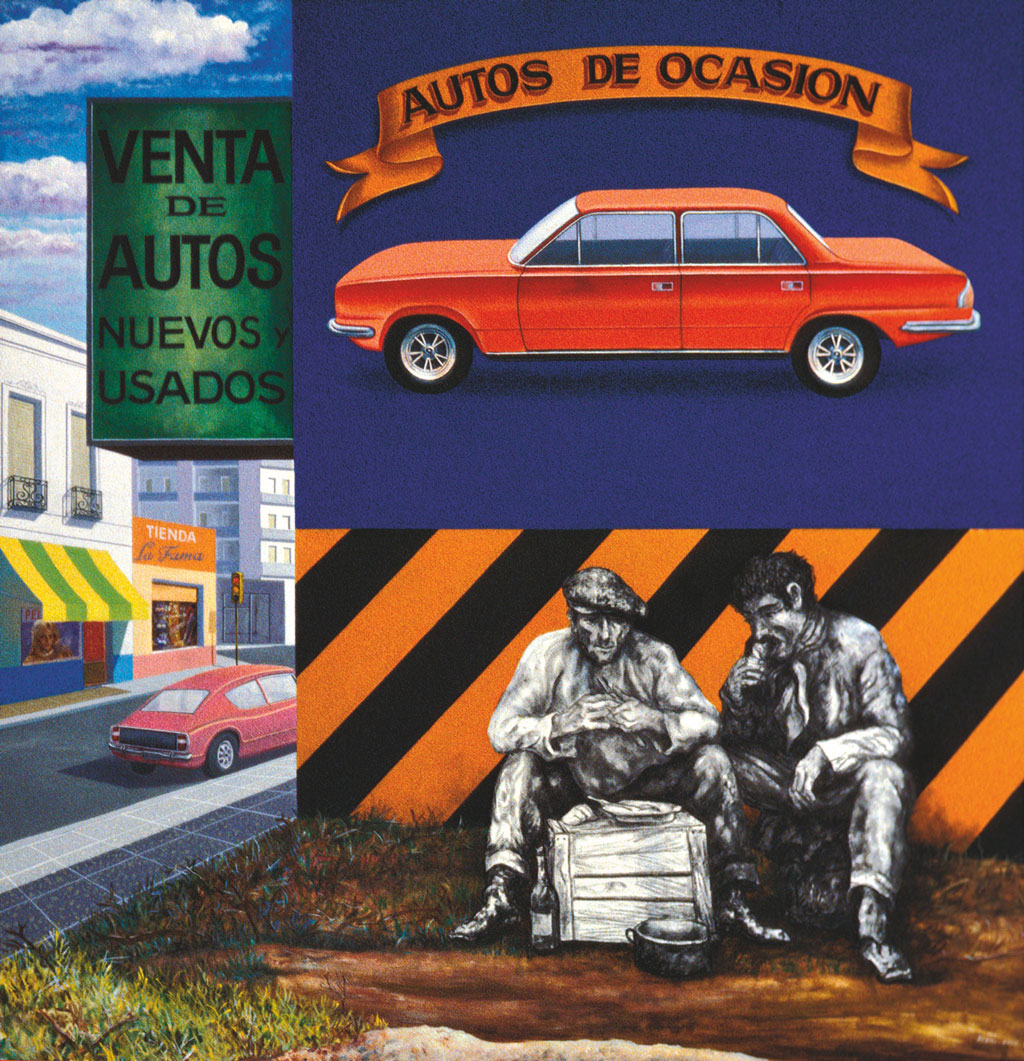

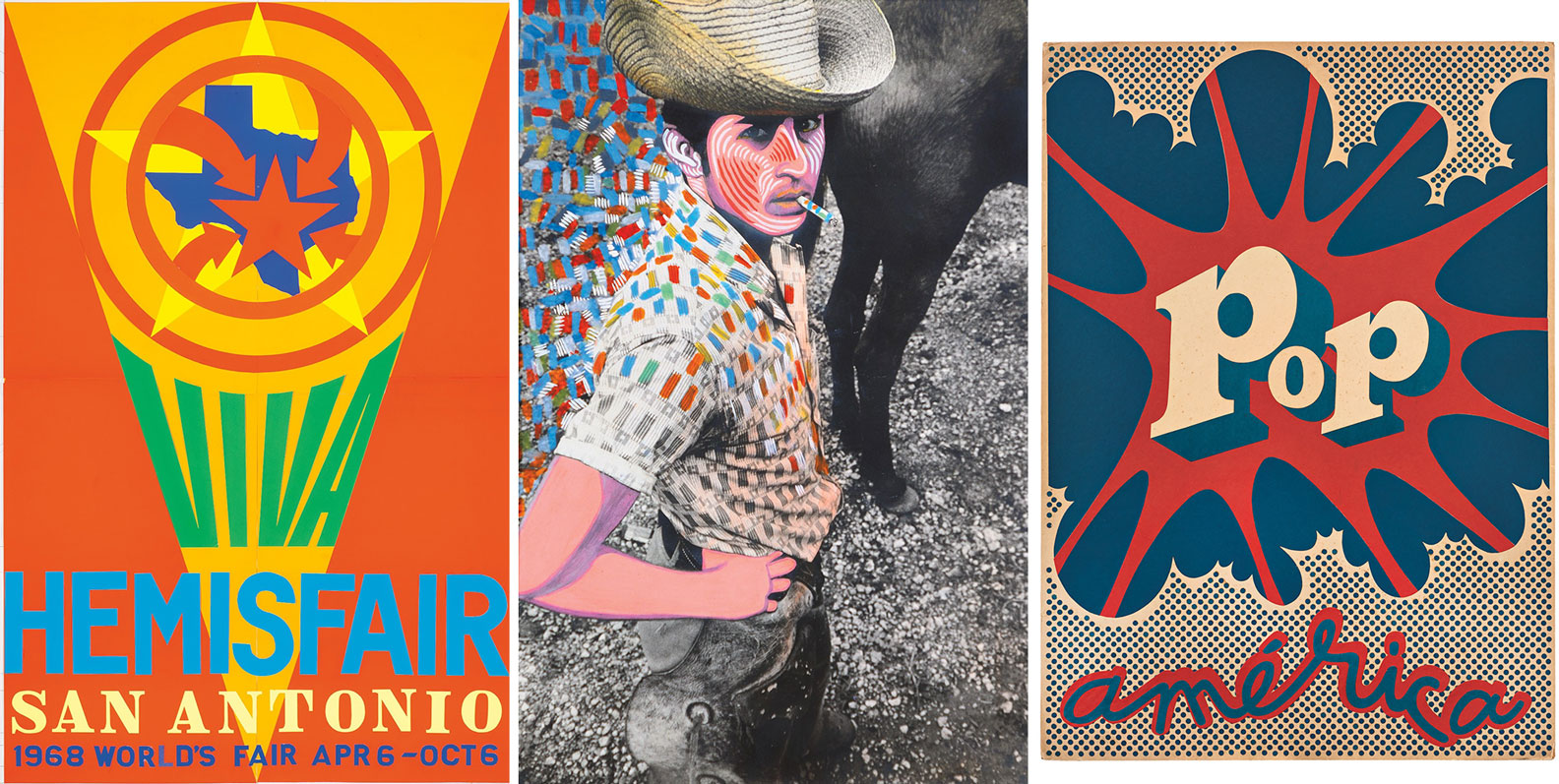

The exhibition “Pop América, 1965-1975” features nearly 100 artworks by artists working in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Mexico, Peru, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, and the United States, sparking an expansion and reconsideration of Pop as a US and British phenomenon. The exhibition reshapes debates over Pop’s perceived political neutrality and aesthetic innovations. The artists in the exhibition create vital dialogues that cross national borders and include Antonio Dias, Rubens Gerchman, Roy Lichtenstein, Marisol, Cildo Meireles, Marta Minujín, Hugo Rivera-Scott, and Andy Warhol, among others. United by their use of Pop’s visual strategies, these artists have made bold contributions to conceptualism, performance, and new media art, as well as social protest, justice movements, and debates about freedom. The exhibition’s centerpiece is the side-by-side display of Roy Lichtenstein’s “Explosion” (1962) and Hugo Rivera Scott’s “Pop América” (1968) . Lichtenstein’s signature comic book blast rendered with bold lines and Benday dots emblematizes obliteration. It’s his rumination on the knock-out punch Pop was serving up to Abstract Expressionism and a very real meditation on the near-miss of nuclear annihilation intimated by the Crisis de Octubre/Cuban Missile Crisis of the same year. Scott’s Lichtenstein-conversant work appears more whimsical. Originally intended as the cover of Eduardo Parra’s unpublished book of poems by the same name, the cardboard collage is more splat than boom, more whimper than bang. The word “Pop” in blue and white, 3-D font hovers atop a burst of red and seems only a centrally situated backdrop to the negative cloud-shaped relief that hosts the ironically plucky cursive “américa” overlaid in the foreground. The difference between the two works is tonal, both in hue and timbre. The shared shapes, revolutionary impulse, and transnational transit between the two works (both traveled internationally), however, set a tone for what permeates seemingly isolated frames. When considering Latin American Pop art, though, it becomes clearer that the broader movement was not simply a stylistic reaction to the Abstract Expressionism that preceded it. Instead, it was a way for Latin American artists who were working under politically repressive regimes to convey radical political statements to the public through seemingly innocuous visual language. For example the blue and grey painting “Unfinished Man” (1968) Rupert García, at first glance, the painting is just the lower part of a face, an open mouth, composed with bold geometries and clean divisions of color. But context is key. The man’s partial face embodies the anxieties (artistic, political, and emotional) that haunted the artist around 1968, when students and black and Chicano civil rights activists protested across the country García, who at the age of 78 is still making work, ise one of the most important American artists of the 20th century. His 1973 poster “¡Cesen Deportación!” featuring rows of barbed wire rendered against a backdrop of stark colors made as potent a statement as ever when it was exhibited in 2017 at Los Angeles’s Craft and Folk Art Museum, shortly after Trump made the announcement that he would be phasing out DACA. In other works, the contamination is ecological or economic. A sampling of Nicolás García Uriburu’s print series “Colorations” reiterates his 1968 action on the eve of the Venice Biennale when he dyed the city’s canals green with a non-toxic tracer. This was, according to Uriburu, “Art on a Latin American scale” meant to draw attention to the interconnected ravages of water pollution. In the accompanying prints the Kelly green pollutes everything from Iguazú Falls to a man’s denuded member. Then there’s Cildo Miereles’s “Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Coca-Cola Project” (1970) in which he silkscreened recipes for Molotov cocktails and slogans like “Yankee go home” camaflouged almost imperceptibly onto glass Coke bottles and recirculated them through the routes of insidious neocolonial consumption. Artist in the exhibition:

Artists in the exhibition: Antônio Henrique Amaral, Asco [Collective] including Harry Gamboa, Jr., Gronk (Glugio Nicandro), Willie F. Herrón III and Patssi Valdez, Luis Cruz Azaceta, Judith F. Baca, Antonio Berni, Antonio Caro, Melesio Casas, Eduardo Costa, Geraldo de Barros, Jorge de la Vega, Antonio Dias, Marcos Dimas, Emory Douglas, Felipe Ehrenberg, Marisol (Escobar), José Gómez Fresquet (Frémez), Rupert García, Rubens Gerchman, Edgardo Giménez, Alberto Gironella, Beatriz González, Juan José Gurrola, Robert Indiana, Carlos Irizarry, Roberto Jacoby, Julia Johnson-Marshall, Nelson Leirner, Roy Lichtenstein, Anna Maria Maiolino, Raúl Martínez, Cildo Meireles, Marta Minujín, Sergio Mondragón, Gronk (Glugio Nicandro), Hélio Oiticica, Claes Oldenburg, Lázaro Abreu Padrón, Dalila Puzzovio, Margaret Randall, Hugo Rivera-Scott, Emilio Hernández Saavedra, Rubén Santantonín, Elena Serrano, Dugald Stermer, Jan Stornfelt, Taller 4 Rojo, including Diego Arango and Nirma Zárate, Nicolás García Uriburu, Andy Warhol and Lance Wyman.

Info: Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University, 40 Arts Circle Drive, Evanston, IL, Duration: 21/9-8/12/19, Days & Hours: Tue & Sat-Sun 10:00-17:00, Wed-Fri 10:00-20:00, www.blockmuseum.northwestern.edu