TRACES: Peggy Guggenheim

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Marguerite “Peggy” Guggenheim (26/8/1898-23/12/1979), The woman that created one of the most important Collections of Modern European and American art. Relying on advisors, including Marcel Duchamp and the anarchist poet and critic Herbert Read, Guggenheim quickly amassed paintings by the most avant-garde European artists before the outbreak of World War II. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history.

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Marguerite “Peggy” Guggenheim (26/8/1898-23/12/1979), The woman that created one of the most important Collections of Modern European and American art. Relying on advisors, including Marcel Duchamp and the anarchist poet and critic Herbert Read, Guggenheim quickly amassed paintings by the most avant-garde European artists before the outbreak of World War II. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history.

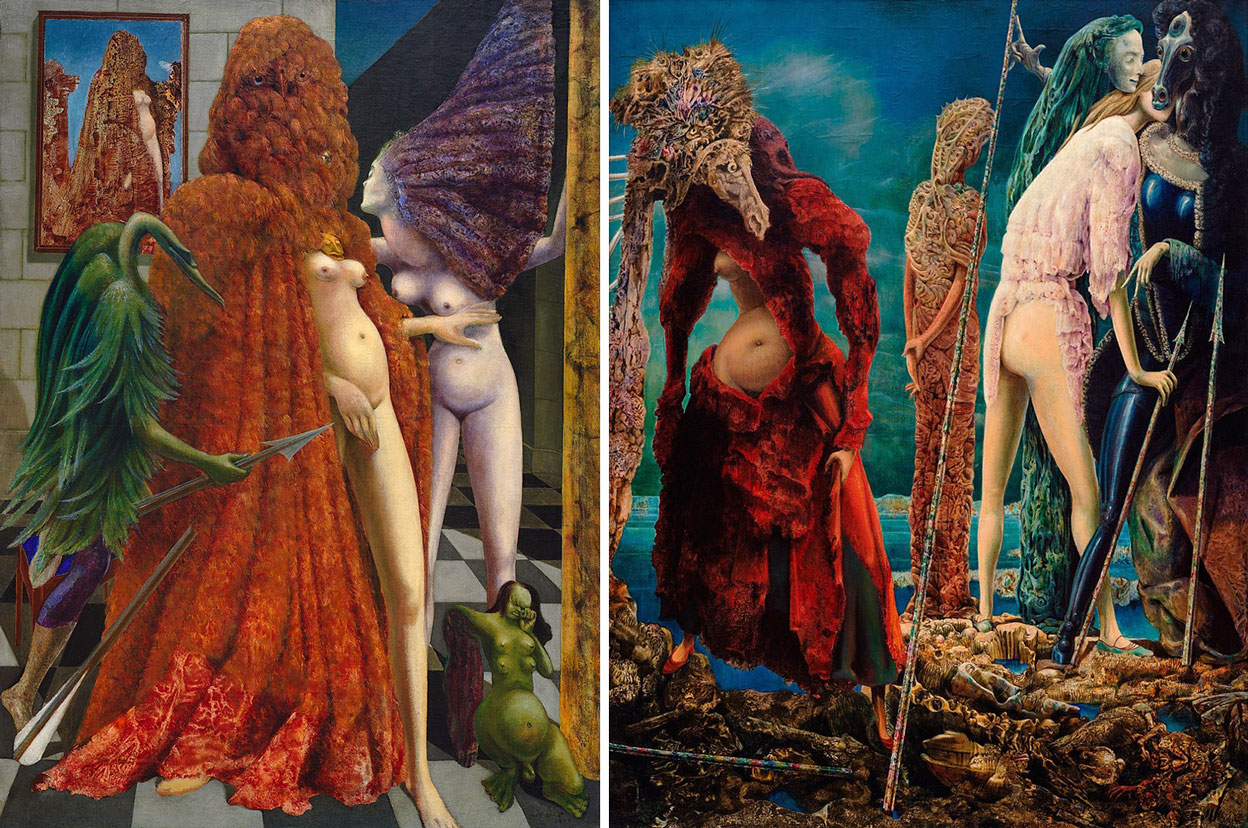

By Efi Michalarou

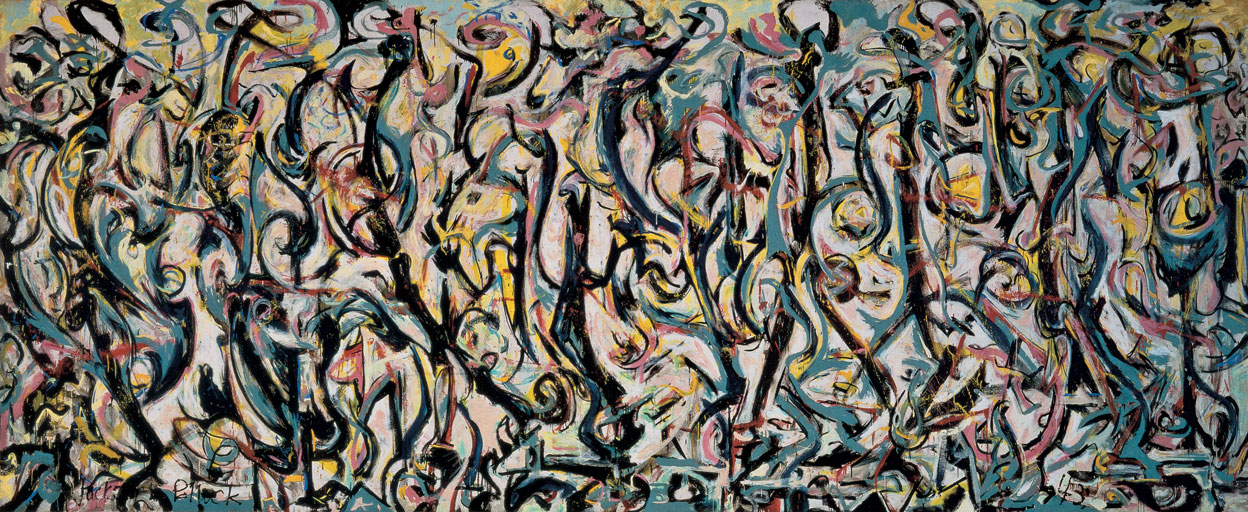

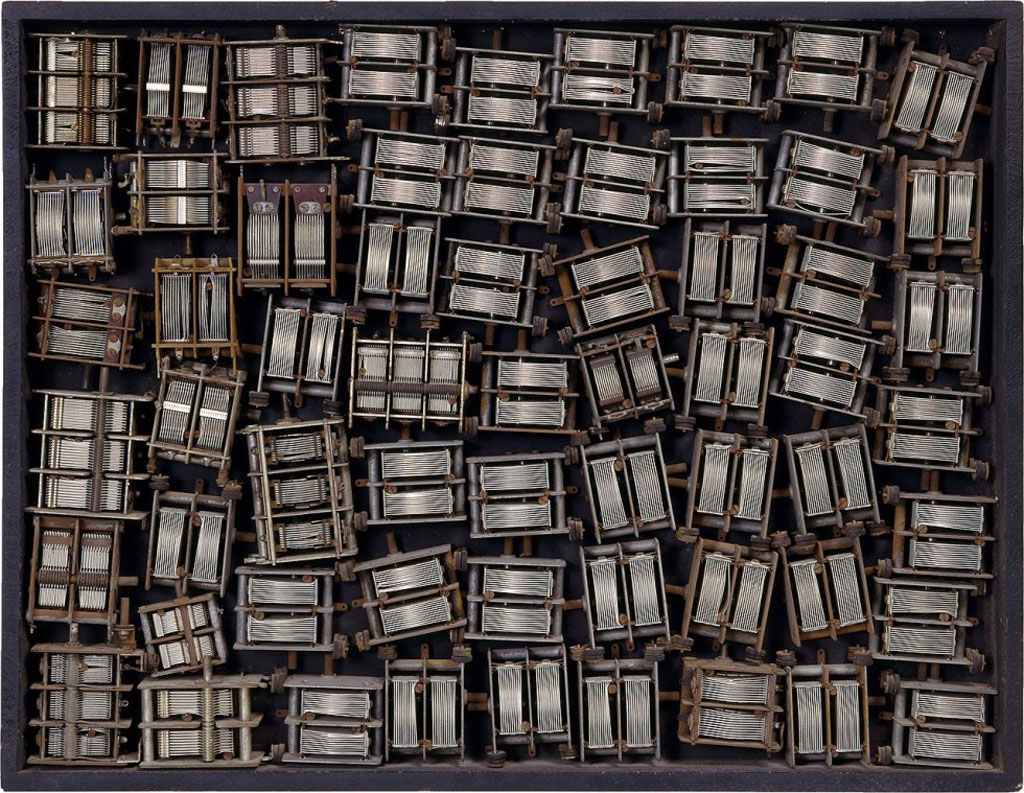

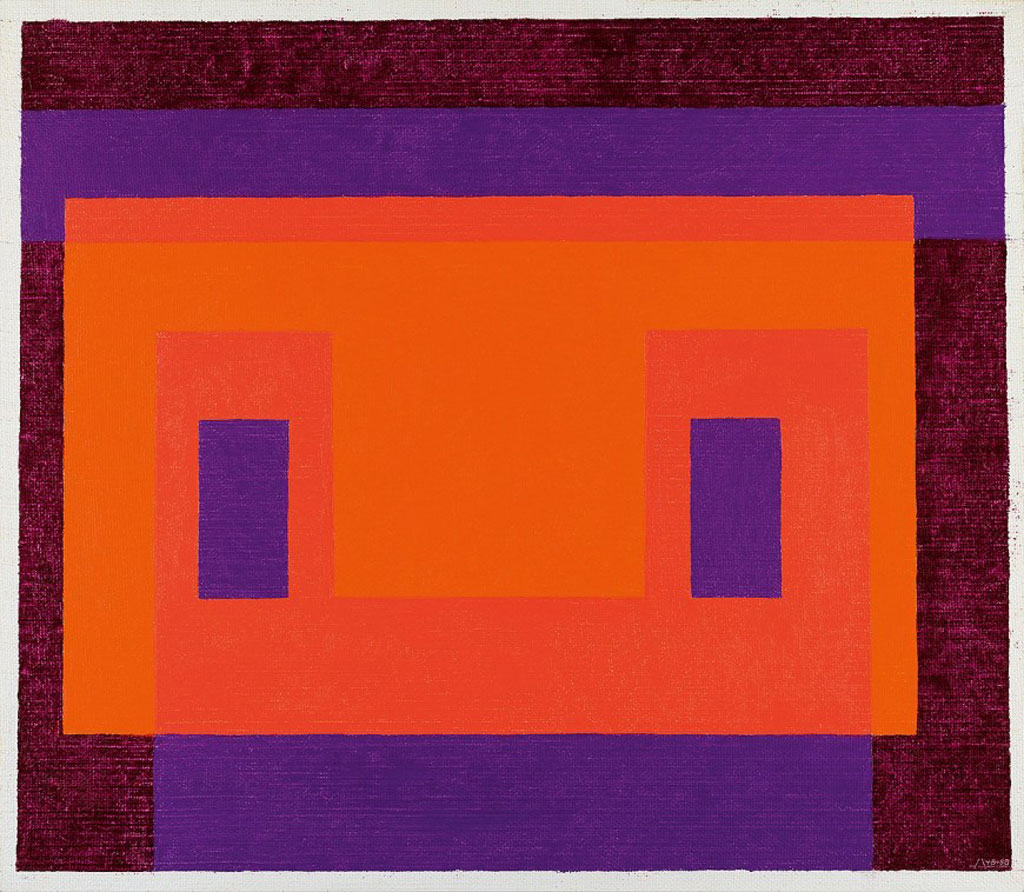

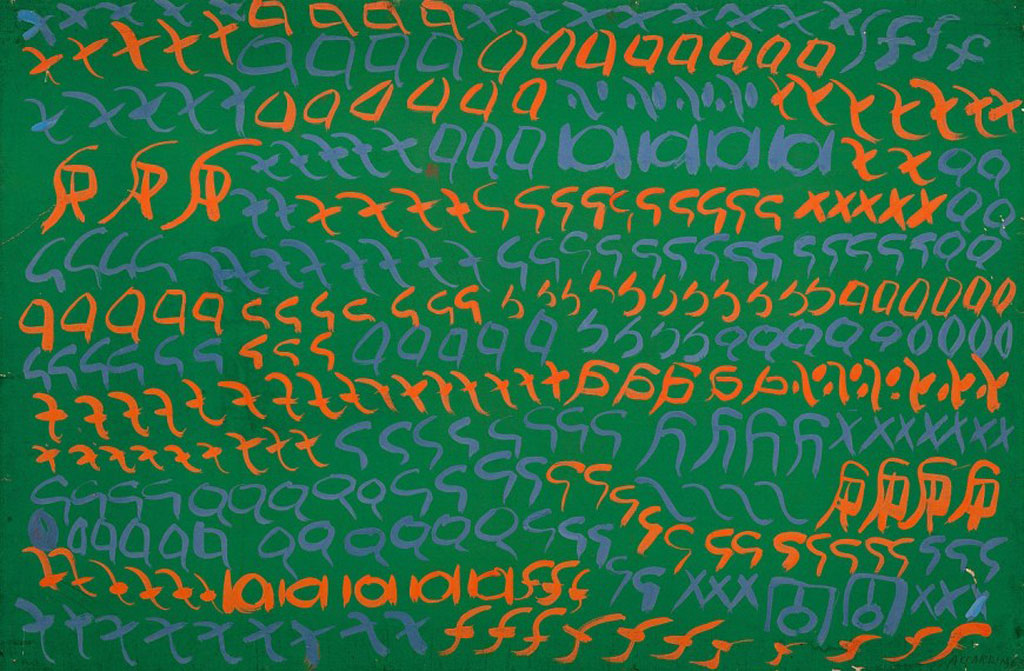

Marguerite Guggenheim, known throughout her life as Peggy, was born into the massively wealthy Guggenheim family Her father, Benjamin, was the fifth of Meyer Guggenheim’s seven children and her mother, Floretta Seligman, came from a New York banking family. She was barely a teenager, however, personal tragedy struck the family when Benjamin Guggenheim died as a passenger on the Titanick. Foregoing college, Guggenheim first worked in support of the war effort, in 1920, she began working as an unpaid assistant at “Sunwise Turn” a midtown Manhattan Avant-Garde bookstore, founder by Mary Horgan Mowbray-Clarke, and Madge Jenison. At the end of 1920, Guggenheim moved to Paris where she explored her interest in Classicall and Renaissance art. She became close friends with Avant-Garde writers, including Romaine Brooks, Djuna Barns, and Natalie Barney, and artists, notably Marcel Duchamp who became her lifelong friend and mentor. At the age of 23, wanting to lose what she called her “burdensome” virginity, she became involved with the artist and writer Laurence Vail. They married in 1922 and had two children Sinbad and Pegeen. The marriage was marked by intense conflict and Vail’s physical abuse, and they divorced in 1928. Her personal relationships were all similarly difficult, marked by infidelity, by husbands who diminished her, perhaps because they felt threatened by their dependency on her wealth. Subsequently she fell in love with the writer John Farrar Holms, and the two began traveling. In 1934 Holms, who was a severe alcoholic, died suddenly during a routine surgical procedure, and Guggenheim moved in with Douglas Garman with whom she had become involved the year before. When that relationship, too, came to an end after several turbulent years, she found herself at a loss for an occupation, since she had never been anything but a wife. After ending her relationship with Garman, Guggenheim found herself at loose ends. Looking for an occupation, she followed the suggestion of a friend and opened a London art gallery named “Guggenheim Jeune”, in January 1938. The gallery’s first show, featuring works by the artist and poet Jean Cocteau and curated by Marcel Duchamp, was a success. The gallery held Kandinsky’s first solo exhibition in Britain, exhibited the works of Wolfgang Paalen and Yves Tanguy, and held group exhibitions of sculpture and collage, featuring: Henry Moore, Alexander Calder, Jean Arp, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Kurt Schwitters, and Constantin Brancusi. Guggenheim began her practice of purchasing at least one artwork from each exhibition, building her own collection. The first work she bought was Jean Arp’s “Shell and Head” (1933). She also freely explored her own sexuality, having hundreds of affairs and brief encounters, with artists like Tanguy and writers like Samuel Beckett. The gallery was a critical success but lost money the first year, and, as a result, Guggenheim thought a contemporary art museum might be a better route. She began working with art historian Herbert Read on a plan to develop a Museum of Modern Art in London. In 1939, she closed the “Guggenheim Jeune” and, subsequently, travelled to Paris with Read’s list of artworks that they hoped to have for their proposed first exhibition. On 1/9/1939, World War II broke out, but, undeterred, Guggenheim decided to buy paintings by all the painters who were on Herbert Read’s list. She was aided in her quest by a number of friends who advised her, including Howard Putzel, an art dealer, and Madame van Doesburg, widow of the painter Theodore van Doesburg, as well as by the desperation of the times. Many artists and art dealers were eager to sell whatever works they could and flee the invading Germans. Buying works by Picasso, Ernst, Magritte, Man Ray, Dalí, Klee, Chagall, Miró, and other artists, she was able to create the nucleus of one of the great modern art collections with $40,000. When Paris was invaded in 1940, she remained in the country, trying to make arrangements to preserve her new collection. Finally hitting upon a plan of shipping them to the United States as household items, she packed them with casserole dishes and household bedding for shipment by boat. In 1941 she returned to New York, along with Max Ernst, whom she subsequently married. At the same time, that world was changing as many European artists immigrated to New York, fleeing World War II and Nazi Germany. In 1942, Guggenheim opened her “Art of This Century Gallery” with sections devoted to Surrealism, Kinetic art, Cubist, and Abstract Art. Frederick Kiesler designed the innovative gallery to create a totally modern experience; some paintings were hung on universal joints, which allowed viewers to turn the paintings to experience different angles of light, thus, creating a more intimate relationship between the viewer and the work. He created an unusual lighting design that occasionally plunged an entire gallery into darkness, and his furniture acted both as seats for gallery-goers as well as easels for paintings. Through her trusty advisor Howard Putzel, Guggenheim began discovering American artists. She became an early patron of Jackson Pollock, providing him with a monthly stipend, his first commission, and his first exhibition. With her 1942 Exhibition by 31 Women, Guggenheim also held the first exhibition solely devoted to women artists, though it had unexpected personal consequences. One of the artists was Dorothea Tanning with whom Max Ernst fell in love, leading to his divorce from Guggenheim in 1946. In 1946 Guggenheim published “Out of This Century: Confessions of an Art Addict” her autobiography that created something of a scandal due to her honest and revealing recount of hundreds of affairs and sexual encounters she had had with various writers and artists. Her family was dismayed, as her wealthy uncles tried unsuccessfully to buy up all the copies, and critical response was equally dismissive. Wanting a fresh start, she closed her gallery in 1947 and moved to Venice, which she called “the city of her dreams”. In 1948, the Venice Biennale invited her to exhibit her collection, which marked the first time the works of Pollock, Mark Rothko, and other American artists had been seen in Europe. She subsequently bought the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, an unfinished 18th Century building on the Grand Canal, where she resided the rest of her life. In Venice, she became a celebrity, known for her butterfly sunglasses, designed by Edward Melcarth, which she wore everywhere as she navigated the city in her private gondola and her accompanying dogs. Her home was a hub for visiting writers and artists, and she also promoted the works of emerging Italian artists like Marini. In 1951, she opened her home as a Museum to the public, and in the subsequent decades, she also loaned her collection to various museums in Europe and the United States. Despite her successful life as a collector and though she had a number of liaisons with young Italian men, she was frequently lonely, writing in a letter, “God forbid my ever getting too attached again in my life to anyone. So far everyone I loved has died or made me madly unhappy by living. Life seems to be one endless round of miseries. I would not be born again if I had the chance”. Guggenheim continued collecting art until about 1973, and in 1962 Venice bestowed upon her an Honorary Citizenship. She died in 1979, and her ashes remain on the grounds of the Venetian palazzo that houses her Collection.