ART-TRIBUTE:Pattern and Decoration-Ornament as Promise

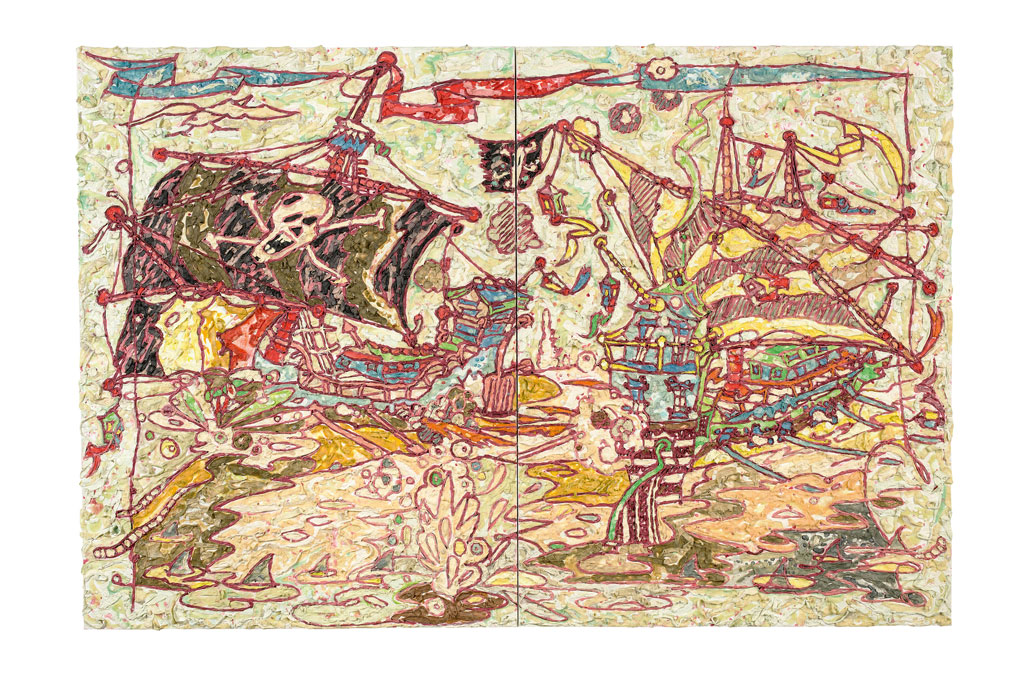

With oriental-style mosaics, monumental textile collages, paintings, installations, and performances, artists associated with Pattern and Decoration Movement aimed in the 1970s to bring color, formal diversity, and emotion back into art. Decoration played a key role, as did the techniques of artisanship associated with it. Various ornamental traditions, from the Islamic world to Native American art to Art Deco, were incorporated in their works, opening up a view beyond geographical and historical boundaries. A proximity to folk art and kitsch was welcomed as a deliberate counter to the “purism” of the art of the 1960s.

With oriental-style mosaics, monumental textile collages, paintings, installations, and performances, artists associated with Pattern and Decoration Movement aimed in the 1970s to bring color, formal diversity, and emotion back into art. Decoration played a key role, as did the techniques of artisanship associated with it. Various ornamental traditions, from the Islamic world to Native American art to Art Deco, were incorporated in their works, opening up a view beyond geographical and historical boundaries. A proximity to folk art and kitsch was welcomed as a deliberate counter to the “purism” of the art of the 1960s.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Mumok Archive

The exhibition “Pattern and Decoration Ornament as Promise” with its reference to Adolf Loos’s assertion concerning “ornament and crime,” presents Peter and Irene Ludwig’s rich collection of works from the Pattern and Decoration Movement (USA, 1975-85), in the largest presentation of the Movement in German-speaking Europe since the 1980s. In 1908 Austrian architect Adolf Loos published his notoriously polemic work “Ornament and Crime” in which he reacted to Vienna Art Deco by declaring decoration a criminal act. Loos saw the absence of decoration as a sign of a highly evolved culture, while the use of decoration was a “crime against the national economy”. The exhibition reverses Loos’s polemic in line with the goals of the Pattern and Decoration Movement. While Loos’s position advocates “high art” in unmistakably misogynist and colonialist tones, Pattern and Decoration represents a search for alternatives to the values of the Western industrial nations for different gender relations and cultural identities, and not least for a new concept of art. Pattern and Decoration can be seen as a paradigmatic art movement of the 1970s. The art historian Hal Foster criticized the art of the 1970s as “promiscuous”. After the “purist” endeavors of the 1960s, and especially of Minimal Art, he felt that the art of the 1970s lacked both a clear style and critical awareness. But Pattern and Decoration was a very deliberately “promiscuous” movement. The result of debate and discussion between artists who knew each other as friends and acquaintances, and the critic Amy Goldin, it was perhaps the last true art movement of the 20th Century, and the first that engaged with diverse decorative traditions from a truly global perspective.

A course in Chinese painting that Brad Davis took while studying at Hunter College in New York in the late 1960s left a lasting impression on him. It was the beginning of a lifelong fascination with Asian art, from motifs to compositional principles to the brushstroke, which would also be shared by other artists in the Pattern and Decoration Movement.

Frank Faulkner’s paintings evoke multiple associations, resembling large tapestries or Persian rugs while at the same time reviving the aesthetics of ancient metalwork or wooden screens. Their complex surfaces, built up from many layers of paint, often reflective and metallic, underscore the notion that the history of fine art cannot be separated from craftsmanship. Like most Pattern and Decoration artists, Faulkner was active in New York in the mid-1970s and participated in a number of exhibitions devoted to the movement. T

ina Girouard’s interest in patterns and her use of elements of interior decoration has secured her a place in the Pattern and Decoration milieu. In fact, however, her work grew out of New York’s experimental art and dance scene in the 1960s and early 1970s. She was a founding member of a series of alternative performance and exhibition spaces, including 112 Green Street and FOOD, and worked with artists including Trisha Brown and Gordon Matta-Clark. Of the artists associated with Pattern and Decoration are:

Valerie Jaudon who in her paintings most closely maintains the geometric abstraction of Modernism. Early in her career, Jaudon declared in an interview that “emphasizing the peripheral stabilizes the center”. Conventions and values had to be shifted and rebalanced from the inside out. Accordingly, after periods of study in Mexico and London as well as trips to Morocco and across Europe, the artist found inspiration in the oeuvre of Frank Stella, who had likewise experimented in his early works with symmetrical arrangements of uniformly broad, monochrome stripes.

Joyce Kozloff, like Miriam Schapiro a founding member of the feminist Heresies Collective, began her career as a painter. During a lengthy sojourn in Mexico in 1973, intense exploration of local ornamental traditions prompted her first to question the conventional hierarchical distinction between “high” and decorative art, and then to interpret details of motifs from woven rugs or ceramic tiles in her paintings on an increasingly large scale. Her ongoing preoccupation with geometric patterns in Islamic art, a trip to Morocco, and, not least, discussions with the artists who in 1975 had joined forces under the banner “Pattern and Decoration” left Kozloff dissatisfied with merely depicting ornamental systems. She decided to quit canvas and soon afterwards realized her first installation.

While studying at the University of California in San Diego, Robert Kushner met not only Kim MacConnel—who shared his fascination with Oriental carpets, kitsch, and Chinese clip-art books with motifs to cut out and collage, but also the art historian Amy Goldin, one of the key voices in theoretical discussions of the Movement. After moving to New York in 1972, the artist worked primarily on performance pieces, presenting them at art spaces such as 98 Greene Street, an alternative loft space directed by the art collector and later gallery owner Holly Solomon and her husband, Horace. Inspired by fashion shows, pageants, masquerade balls, and cabaret, Kushner’s performances featured costumes he made himself from everyday materials.

Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt’s art got swept up in the slipstream of Pattern and Decoration through his association with the Holly Solomon Gallery in New York. With his affinity for knick-knack and kitsch and his ability to create highly decorative objects and settings out of cheap materials such as aluminum foil, cellophane, plastic beads, and tinsel, his work suggests straightforward formal analogies and yet also resonates with a deeper, quasi-anthropological dimension. Coming from a Catholic working class background and already openly homosexual before the Stonewall uprising of 1969, in which he was actively involved, Lanigan-Schmidt addresses in his art the complex entanglements between class, religion, and sexuality.

When Kim MacConnel was studying at the University of San Diego in California in the late 1960s with Robert Kushner, he met the art critic Amy Goldin, who would become a mentor to both artists. Goldin’s enthusiasm for Islamic art animated MacConnel to research Oriental kilims (woven nomadic rugs) and the ikat weaving technique, in which the yarn is dyed in sections before being woven. He then began in 1975 to produce textile collages made up of vertical lengths of fabric, inspired by the wall hangings in nomads’ tents, which often made use of remnants from weavings and rug scraps.

When Miriam Schapiro helped launch the Pattern and Decoration Movement, she was already in her early fifties and thus almost a generation older than most of her colleagues. Shaped by her experiences as a woman painter in the sexist environment of the New York Abstract Expressionists, she had founded the Feminist Art Program at the California Institute of the Arts in Los Angeles with Judy Chicago in 1971, one of the key institutions for the advancement of feminist art in the USA. The program’s goal was to encourage female artists to relate their lives, experiences, and fantasies to their work. Schapiro was also a founding member of the Heresies Collective, a women’s group that published the periodical “Heresies. A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics” (1977–93). Pattern and Decoration offered Schapiro a context in which she could visually articulate her feminist agenda.

Kendall Shaw was born in 1924 in New Orleans, where he was exposed to jazz and ragtime at an early age through his father, a pianist, and later studied both chemistry and painting. A generation older than most of his Pattern and Decoration peers, he first fell under the sway of Abstract Expressionism before turning in 1966 to abstract rhythmical paintings based on enlarged photographs of his wife Frances’s patterned and striped dresses. In the early 1970s, Shaw then began to paint his own patterns and found in Pattern and Decoration a congenial context for his interest in visual rhythm and the play of color and energy across a surface. His paintings from those years, built up layer by layer over extended period

Ned Smyth embarked on his artistic career in New York in the early 1970s, crafting architectural tableaux out of basic structural forms in cast concrete (cylinders, steles, arches) that borrowed from both Minimalism and classical monuments. As the son of Renaissance art historian Craig Hugh Smyth, the artist spent time in Italy as a child and the European art he saw there would leave a lasting impression. Smyth met the painter Brad Davis through the Holly Solomon Gallery, and the two realized the joint installation “The Garden” in 1977, which combined painting and sculpture resonating with both Western and Eastern references into an all-encompassing decorative ensemble.

When Robert Zakanitch organized the first informal meetings on the topics of “pattern” and “decoration” at his New York loft in 1975, with the help of Miriam Schapiro, he had already made a name for himself with his Color Field paintings. After working in an Abstract Expressionist and Surrealist manner, he had arrived at an individual formal idiom featuring the subtlest of color gradients arranged in grids on large canvases. Like Schapiro, Zakanitch was however seeking to exceed the boundaries of formalist painting, and so he began experimenting with different forms of mark-making, leading in 1975 to his first picture with an unmistakably floral motif.

Through his connection with the Holly Solomon Gallery in New York, which played a crucial role in the success of Pattern and Decoration, Joe Zucker’s work became associated with the movement. Common ground can be found in Zucker’s ongoing engagement with the grid as well as his interest in painting as a craft and in tactile surfaces. After years of preoccupation with the grid-like woven structure of the canvas, Zucker developed a technique in 1969 that enabled him to approach the elementary conditions of painting from a different angle: he began to construct paintings out of cotton balls soaked in acrylic paint, applying them to the canvas like mosaic pieces. In 1973 Zucker expanded his technique by adding the colorless binder Rhoplex, which makes the cotton wool malleable and shapeable, allowing him to “sculpt” brushstrokes.

Info: Curator: Manuela Ammer, Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien (mumok), Museumsplatz 1, Vienna, Duration: 23/2-8/9/19, Days & Hours: Mon 14:00-19:00, Tue-Wed & Fri-Sun10:00–19:00, Thu 10:00-21:00, www.mumok.at