TRACES: Joseph Beuys

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the German artist Joseph Beuys (12/5/1921-23/1/1986). He was the artist with the most influence in the artistic reality of Post-War Europe and America. If Marchel Duchamp, is considered as the father of Contemporary Art, Joseph Beuys is the Patriarch. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the German artist Joseph Beuys (12/5/1921-23/1/1986). He was the artist with the most influence in the artistic reality of Post-War Europe and America. If Marchel Duchamp, is considered as the father of Contemporary Art, Joseph Beuys is the Patriarch. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

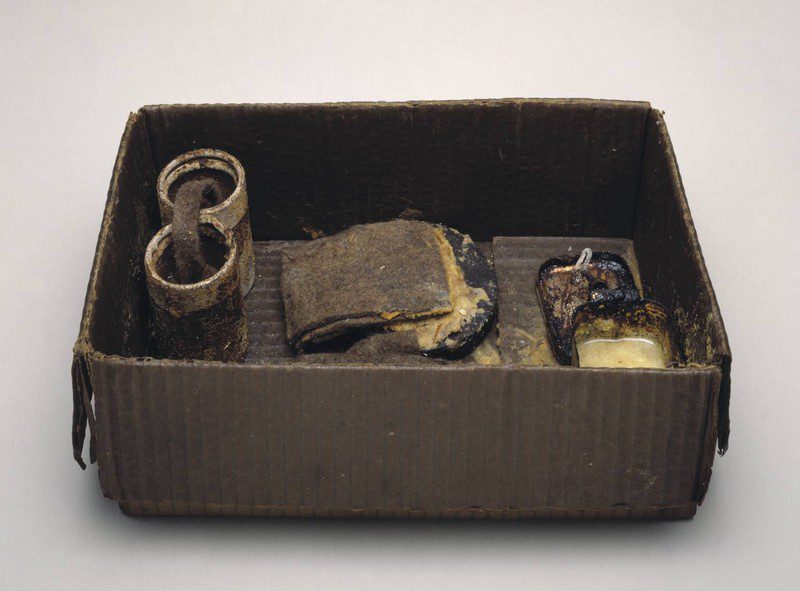

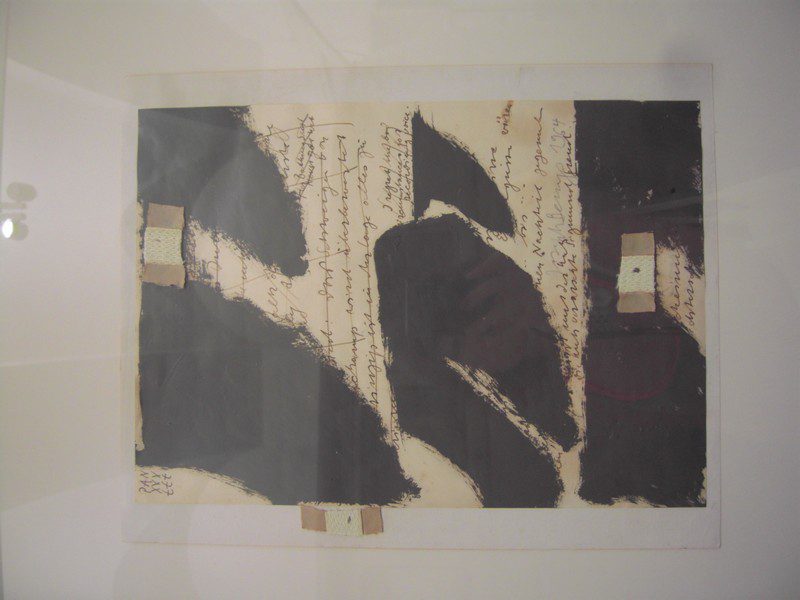

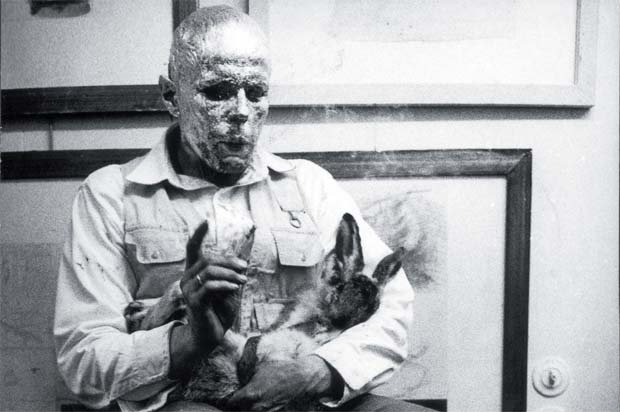

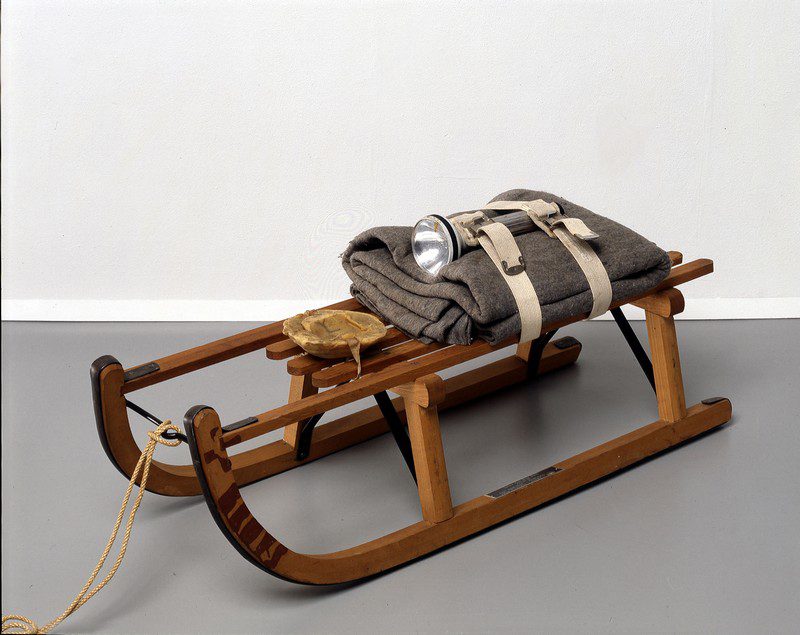

Born in 1921 in the town of Krefeld, Beuys served in the German air force throughout World War Two. In 1943, his plane was shot down over the frozen Crimea. He was rescued from the crash by nomadic Tatar tribesmen. Those who found him tried to restore his body heat by wrapping him in fat and an insulating layer of felt, which is likely the origin of the recurring materials in his sculptural works. At the end of the war he was held in a British prisoner-of-war camp for several months, and returned to Kleve in 1945. After the war, he studied sculpture at the state art academy in Düsseldorf, where he taught from 1961 to 1972. Beuys was dismissed from his teaching position over his insistence that admission to the art school be open to anyone who wished to study there. During the early 1960s, Düsseldorf developed into an important center for contemporary art and Beuys became acquainted with the experimental work of artists such as Nam June Paik and the Fluxus group, whose public “concerts” brought a new fluidity to the boundaries between literature, music, visual art, performance, and everyday life. Their ideas were a catalyst for Beuys’ own performances, which he called “actions”, and his evolving ideas about how art could play a wider role in society. He began to publicly exhibit his large-scale sculptures, small objects, drawings, and room installations. He also created numerous actions and began making editioned objects and prints called multiples. What served to launch Beuys into the public consciousness was that which transpired following his performance at the Technical College Aachen in 1964. As part of a festival of new art coinciding with the 20th anniversary of an assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler, Beuys created a Performance or Aktion. The Performance was interrupted by a group of students, one of whom attacked Beuys, punching him in the face. Another of these actions was “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare” from 1965. Beuys covered his head with honey and gold leaf, wore one shoe with felt on its sole, another soled with iron. He walked through an art gallery for two hours, explaining the art hanging there to a dead hare that he carried. As the decades advanced, his commitment to political reform increased and he was involved in the founding of several activist groups. In 1979 he was one of 500 founding members of the Green Party. The fact that the complexity of Beuys’s oeuvre is in part a product of these very inconsistencies has sometimes been disregarded in the response to his art: both by his critics, who have found it easier to pigeonhole him, and by admirers who have insisted on an orthodox interpretation. One of the many roles Joseph Beuys assigned himself was that of Shaman/Healer, and he often spoke of a vast social wound that needed cure. His art offered both poetic representations of the injury and practical prescriptions for a cure, and alludes to healing techniques of all kinds, both physical and spiritual. His reputation in the international art world solidified after a 1979 retrospective at New York’s Guggenheim Museum, and he lived the last years of his life at a hectic pace, participating in dozens of exhibitions and traveling widely on behalf of his organizations. Beuys died in 1986 in Düsseldorf.

Born in 1921 in the town of Krefeld, Beuys served in the German air force throughout World War Two. In 1943, his plane was shot down over the frozen Crimea. He was rescued from the crash by nomadic Tatar tribesmen. Those who found him tried to restore his body heat by wrapping him in fat and an insulating layer of felt, which is likely the origin of the recurring materials in his sculptural works. At the end of the war he was held in a British prisoner-of-war camp for several months, and returned to Kleve in 1945. After the war, he studied sculpture at the state art academy in Düsseldorf, where he taught from 1961 to 1972. Beuys was dismissed from his teaching position over his insistence that admission to the art school be open to anyone who wished to study there. During the early 1960s, Düsseldorf developed into an important center for contemporary art and Beuys became acquainted with the experimental work of artists such as Nam June Paik and the Fluxus group, whose public “concerts” brought a new fluidity to the boundaries between literature, music, visual art, performance, and everyday life. Their ideas were a catalyst for Beuys’ own performances, which he called “actions”, and his evolving ideas about how art could play a wider role in society. He began to publicly exhibit his large-scale sculptures, small objects, drawings, and room installations. He also created numerous actions and began making editioned objects and prints called multiples. What served to launch Beuys into the public consciousness was that which transpired following his performance at the Technical College Aachen in 1964. As part of a festival of new art coinciding with the 20th anniversary of an assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler, Beuys created a Performance or Aktion. The Performance was interrupted by a group of students, one of whom attacked Beuys, punching him in the face. Another of these actions was “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare” from 1965. Beuys covered his head with honey and gold leaf, wore one shoe with felt on its sole, another soled with iron. He walked through an art gallery for two hours, explaining the art hanging there to a dead hare that he carried. As the decades advanced, his commitment to political reform increased and he was involved in the founding of several activist groups. In 1979 he was one of 500 founding members of the Green Party. The fact that the complexity of Beuys’s oeuvre is in part a product of these very inconsistencies has sometimes been disregarded in the response to his art: both by his critics, who have found it easier to pigeonhole him, and by admirers who have insisted on an orthodox interpretation. One of the many roles Joseph Beuys assigned himself was that of Shaman/Healer, and he often spoke of a vast social wound that needed cure. His art offered both poetic representations of the injury and practical prescriptions for a cure, and alludes to healing techniques of all kinds, both physical and spiritual. His reputation in the international art world solidified after a 1979 retrospective at New York’s Guggenheim Museum, and he lived the last years of his life at a hectic pace, participating in dozens of exhibitions and traveling widely on behalf of his organizations. Beuys died in 1986 in Düsseldorf.