ART-PRESENTATION: New Order-Art and Technology in the 21st Century

At a time when technology seems utterly smooth and weightless (composed of invisible waves, wireless signals, abstract codes)the works included in the exhibition “New Order: Art and Technology in the Twenty-First Century” highlight the uneasy coexistence of intelligent networks and raw material, the virtual and the physical, the fabricated and the readymade. In this way, the artists in the exhibition confront the fundamental paradoxes of cultural production and technological power in the 21st Century.

At a time when technology seems utterly smooth and weightless (composed of invisible waves, wireless signals, abstract codes)the works included in the exhibition “New Order: Art and Technology in the Twenty-First Century” highlight the uneasy coexistence of intelligent networks and raw material, the virtual and the physical, the fabricated and the readymade. In this way, the artists in the exhibition confront the fundamental paradoxes of cultural production and technological power in the 21st Century.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: MoMA Archive

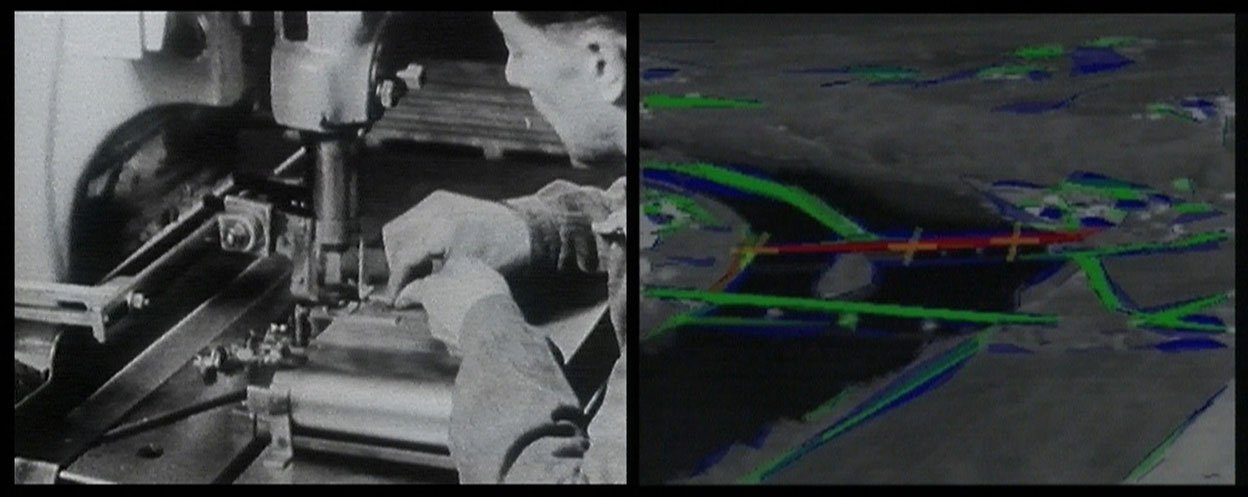

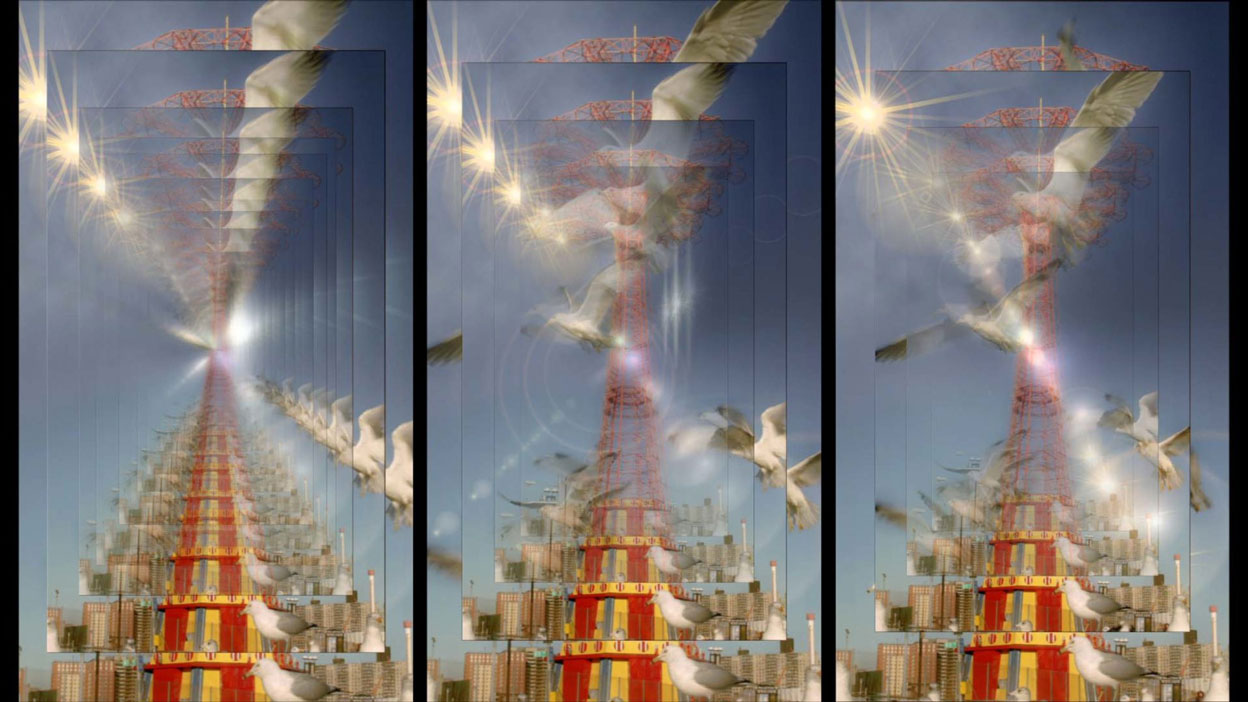

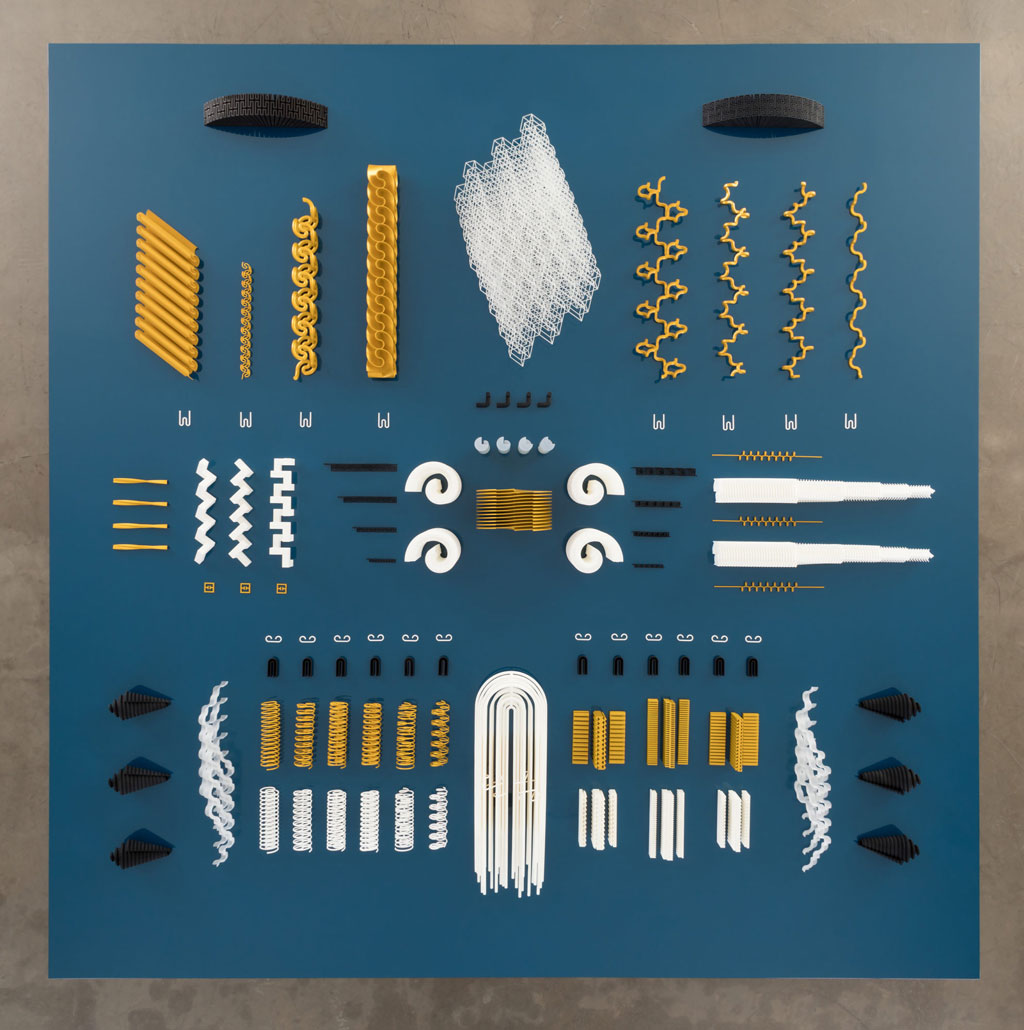

With a number of recent acquisitions and large-scale installations never before shown at the Museum, the exhibition New Order: Art and Technology in the Twenty-First Century” includes works made since the turn of the millennium that push the boundaries of technology and showcases a diverse range of techniques and media, from live digital simulation to 3-D printing, magnetic resonance imaging, industrial vacuum-formed plastic, and ultrasound gel. Technology is never given; it’s made. The artists in the section “Reverse Engineering” actively explore the materials and construction behind different technologies. They highlight the physical infrastructures that drive machines and networks, examining how these systems came to be, how they work, and how they can be undone Technology is transformation—the conversion of matter into energy, data into things, the real into the virtual and back again. Such shifts become visible in the artworks displayed in the section “Stranger Things”. For Harun Farocki technology was never neutral. In the video “Eye/Machine I” (2001) the pioneering filmmaker collected images from military and industrial surveillance devices to explore the increasingly complex relationship between humans and hardware, battlefields and factories, war and capital. On the one hand, we see footage from aerial reconnaissance, targeting, and bombing strikes; on the other, scenes of material production, labor, and manufacturing. Farocki’s work puts the body and the machine side by side, with the former being overtaken by the latter: the eye replaced by automated drones, cameras and weapons. Data is the new most valuable resource. Enabled by the internet and social media, the massive quantities of information being uploaded, aggregated, and exchanged today are crucial to contemporary technologies such as facial recognition. Trevor Paglen in “It Began as a Military Experiment” (2017) traces this recent development to its military origins. The artist selected ten photographs from a database of thousands of images taken of military employees in the mid-1990s used to develop Face Recognition Technology by the US Department of Defense. Faint letters mark the corners of each person’s eyes, noses, and lips. By comparing the physical features of many different faces, an algorithm could be taught how to see and identify individuals. The more faces, the smarter the algorithm. Before social media, Paglen shows us, military research had begun to convert human bodies into ever-growing data sets that could power vast systems of surveillance and control. Scenes of urban upheaval, infrastructure, and engineering are echoed in Basim Magdy’s experimentation with materials. In “The Hollow Desire to Populate Imaginary Cities” (2014), two slide projections, dissolving into one another, feature images of an industrial site being destroyed and reconstructed. To achieve the discoloration in these slides, the artist exposed the film stock to household chemicals, a technique he describes as “pickling”. Magdy has said that his work with destroyed film that came from a need to find a tool to communicate ideas related to loss, destruction, confusion, and the apocalypse. “Unlike digitally altered images”, he explains, “chemically altered film makes the slides tangible objects, a physical testimony to a laborious process”. The dizzying constellation of digitally rendered spirals and vortices in Tauba Auerbach’s “Altar/Engine” (2015) takes shape in specialized resins and polymers. Each structure is an experiment in computer-controlled additive manufacturing, in which material is fused in successive layers. Typically used for rapid prototyping, the technology was here deployed to produce unusually complex geometries. Auerbach focuses on the helix, a spiral shape found throughout both nature and mathematics, as what she calls a “machine that powers the world,” a miraculously universal code or blueprint for life. The sculpture also refers to an exploded diagram of an engine, its parts dismantled to reveal their order of assembly. The delicate forms are both mystical and mechanistic, hovering between two-dimensional graphics and three-dimensional modeling, symmetry and irregularity, irrational belief and rational system. At any one moment, Leslie Thornton’s video “Luna” (2013) depicts seagulls flocking near the long-defunct but still-standing Parachute Jump ride at Luna Park in Coney Island, Brooklyn. This scene is rendered in an array of different media, from black-and-white to color film, broadcast television to digital video, phonography to synthesized audio, all produced through digital manipulation. As this tour of historical formats and infrastructures unspools, Thornton foregrounds the ways in which technology both shapes and is shaped by our understanding of time. Built as an engineering marvel for the 1939 World’s Fair, the amusement park ride is resurrected as a virtual rumination on obsolescence and enchantment. Tabor Robak’s work employs computer generated imaging to create videos of invented worlds. Working in programs including Unity, After Effects, Photoshop and Cinema 4D, the artist explores a secondary, digital reality, rendered in what he refers to as a “Photoshop tutorial aesthetic” or a “desktop screensaver aesthetic”. His meticulously produced and filmed environments are cobbled together from sources both sampled and hand-modeled. The works are appropriative, both in their subject matter and aesthetic, using elements purchased and then edited for his purposes. They adopt the visual vocabulary of contemporary video games in order to isolate and comment upon digital space as an abstract fact, while simultaneously pushing up against the increasingly tenuous separation between perceptions of the digital and the real. “Xenix” (2013) simultaneously shows the modeling of four different weapons. The artist is interested in the connoisseurship of firearms, as well as their presentation in popular media, particularly video games. While the weapon in one corner appears dreamy, sleek with psychedelic colors and little implied violence, another takes the form of a sinister pipe bomb built of household materials. A sniper-rifle looks similar to the guns appearing in mass-market video games, and is neutered by this familiarity – the weapon’s immediate association is with gaming, rather than actual violence. Ian Cheng describes the “Emissary Forks at Perfection” (2015-16) as “A video game that plays itself”, this digital simulation is generated in real time with no fixed beginning or end. Created using the Unity engine, a popular software tool for developing 3-D video games and AI models, the animation takes place far in the future. It tells the story of Talus Twenty Nine, an artificial intelligence that oversees a lush terrain in which new plants and animals constantly evolve in a Darwinian setting. The AI resurrects an ancient cadaver from the twenty-first century, and summons a pet dog to guide the undead through this posthuman world. Every time the program is run, a new scenario unfolds. The result is an endlessly changing, fantastical model of biological evolution and machine learning in the absence of human life.

Info: Michelle Kuoand, Assistant Curator: Lina Kavaliunas, The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York, Duration: 17/3-15/6/19, Days & Hours: Daily 10:30-17:30, https://www.moma.org