TRACES: Franz West

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Franz West (16/2/1947-26/7/2012), who brought a punk aesthetic into the pristine spaces of art galleries. His abstract sculptures, furniture, collages and large-scale works are direct, crude and unpretentious. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Franz West (16/2/1947-26/7/2012), who brought a punk aesthetic into the pristine spaces of art galleries. His abstract sculptures, furniture, collages and large-scale works are direct, crude and unpretentious. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Efi Michalarou

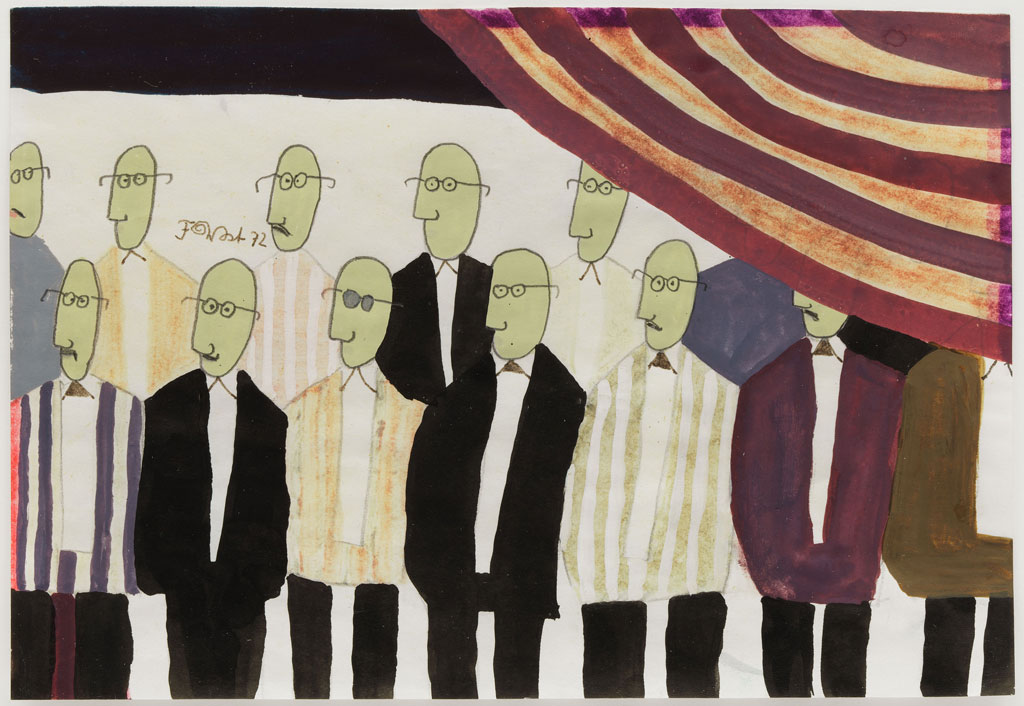

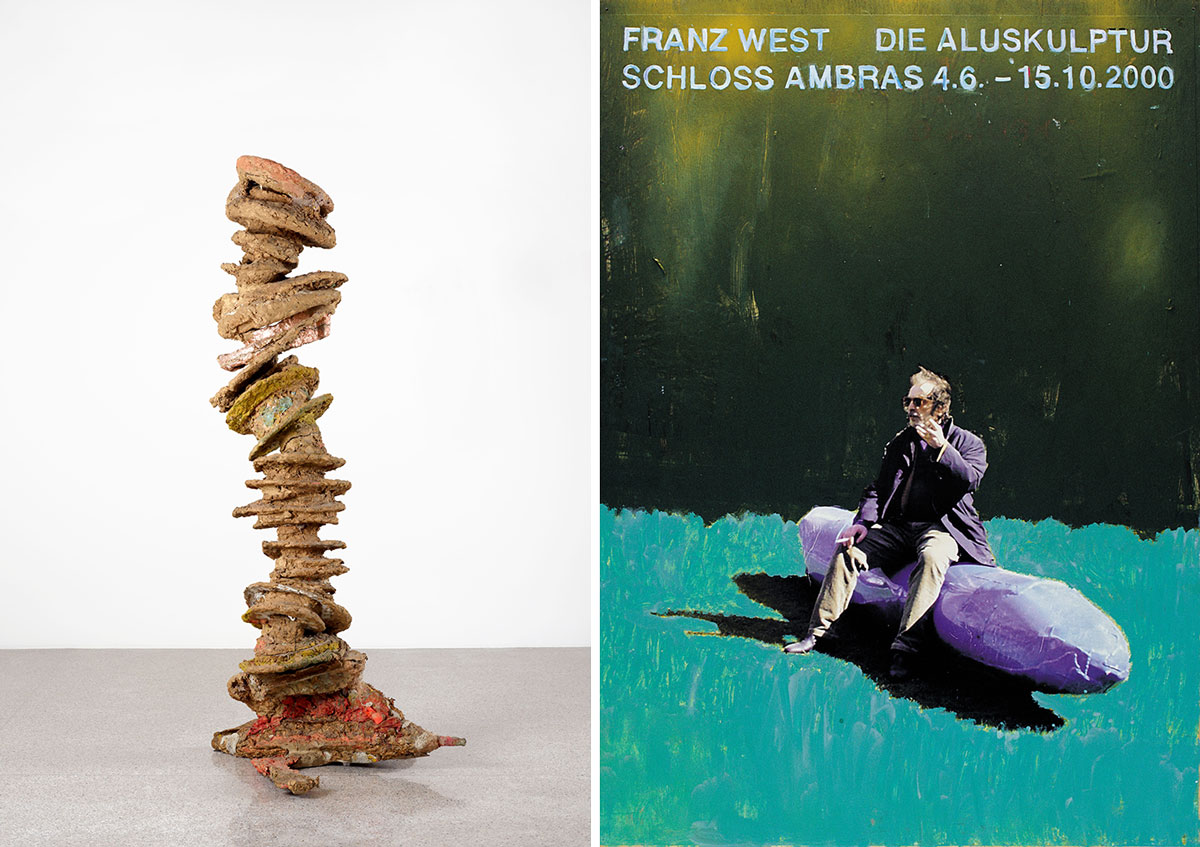

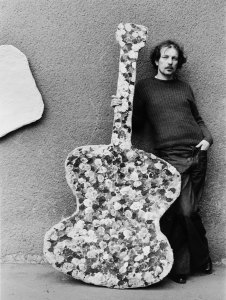

Born in 16/2/1947, Franz West grew up in postwar Vienna, where children played in bomb ruins. His parents were Communists. The family lived in a housing project “full of old Nazis” where his father sold coal and his Jewish mother was a dentist, working in their apartment with primitive equipment. “Every forty minutes, a new patient was screaming”. He studied art intermittently while leading a life, between the ages of seventeen and twenty-five, that he describes as “pretty catastrophic” ridden with drugs and aimless travels, amid café existentialists. He enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna in 1977 (when he was already 30 years old) and studied there under Bruno Gironcoli. The artist sometimes even stated that the only reason for him to start making art was to calm his mother, who was growing impatient of her son’s reluctance to do just about anything with his life. He was familiar with the work of Vienna Actionists and their provocative performances that involved dead animals, self-mutilation, and masturbation – they were the dominant force in the Vienna art scene of the 1960s. West renounced the physicality and existential intensity of that kind of work, focusing instead on benign and relaxed lightness. He once said that his first taste of the Actionist’s performance originated in screams of his mother’s patients, coming from her office next door to the family’s apartment. Instead of gruesomeness and intense display, he chose interaction as his modus operandi, a feature that marked his entire career. By deciding to begin his studies relatively late, it came to be that he already had an understanding of what he wanted to create. Nevertheless, he was inspired by his teacher Bruno Gironcoli, whose overblown sculptures of domestic objects influenced West in the development of his own distinctive idiom. Among his first well-known works are small amorphous objects that are meant to be touched, held, manipulated and contemplated. Called “Adaptives” or “Passstücke”, these pieces exist in their own universe of incompleteness and closeness to the body. They were often created phallus-shaped or had some other sexual allusion behind them, and yet they always remained strongly attached to the abstract world. West described some of the art pieces that he’d made to his friend, poet Reinhard Priessnitz, and he coined the original German name for them – Passstücke. Later, the artist sought an adequate English translation, and had to choose between Fitting Piece and Adaptive, preferring the translation and settling on the latter term. These works represented a truce between performance and art object and reflected the artist’s early admiration for the all-white reliefs and paintings of Piero Manzoni and Robert Ryman. With, of course, one big difference, they were created with the intention to be worn, carried, held, or simply touched by the viewers, giving his practice a true interactive dimension. Much of this later work was developed from ideas implicit in the Adaptives. The artist would sometimes invite others to apply paint or collage to their white surfaces. Before he even noticed, he was creating objects too big to handle, entering the world of “legitimate sculpture”. But even these continued to grow, eventually evolving into considerably larger papier-mâché and cardboard works whose fragmentary shapes and distressed surfaces had an ancient mien, as if they had survived the vicissitudes of time. Then he started making larger, hilariously bulbous, vibrantly colored papier-mâché pieces, something that West is arguably best known for. The possibilities of the found furniture incorporated in some of the Adaptives came to be in the center of his focus in the early 1980s, as he was making spindly chairs and divans out of rebar that parodied elegant furniture while being quite elegant and surprisingly comfortable themselves. His ambition slowly grew. So did his installations, where he now created combinations of sculptures, furniture, paintings, and even works made by other artists. In the late ‘90s, West’s focus turned to lacquered aluminum works, some of them inspired by the shapes of Adaptives. Apart from their appeal, they were o meant for lying and sitting, incorporating the basics of furniture. Despite his desire to remain close to a trash aesthetic (West destroyed any pieces that his friends had the carelessness to describe as beautiful), the work he made towards the end of the 1990s is more refined. Rough forms become streamlined, colours more saturated and convivial, as with “Knotzen” (2002): a trio of hard metal sculptures that look deceptively like brightly painted beanbag chairs. The “Sisyphos” sculptures are amorphous masses of papier-mâché, Styrofoam, and cardboard, expressively painted with lacquer and acrylic. They are named after the mythical first king of Ephyra, who deceived and plotted against others in order to advance his own power and prestige. Zeus punished Sisyphos for his hubris by forcing him to repeatedly roll a heavy boulder up a steep hill, only to have the rock tumble back down just as he reached the top.

Born in 16/2/1947, Franz West grew up in postwar Vienna, where children played in bomb ruins. His parents were Communists. The family lived in a housing project “full of old Nazis” where his father sold coal and his Jewish mother was a dentist, working in their apartment with primitive equipment. “Every forty minutes, a new patient was screaming”. He studied art intermittently while leading a life, between the ages of seventeen and twenty-five, that he describes as “pretty catastrophic” ridden with drugs and aimless travels, amid café existentialists. He enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna in 1977 (when he was already 30 years old) and studied there under Bruno Gironcoli. The artist sometimes even stated that the only reason for him to start making art was to calm his mother, who was growing impatient of her son’s reluctance to do just about anything with his life. He was familiar with the work of Vienna Actionists and their provocative performances that involved dead animals, self-mutilation, and masturbation – they were the dominant force in the Vienna art scene of the 1960s. West renounced the physicality and existential intensity of that kind of work, focusing instead on benign and relaxed lightness. He once said that his first taste of the Actionist’s performance originated in screams of his mother’s patients, coming from her office next door to the family’s apartment. Instead of gruesomeness and intense display, he chose interaction as his modus operandi, a feature that marked his entire career. By deciding to begin his studies relatively late, it came to be that he already had an understanding of what he wanted to create. Nevertheless, he was inspired by his teacher Bruno Gironcoli, whose overblown sculptures of domestic objects influenced West in the development of his own distinctive idiom. Among his first well-known works are small amorphous objects that are meant to be touched, held, manipulated and contemplated. Called “Adaptives” or “Passstücke”, these pieces exist in their own universe of incompleteness and closeness to the body. They were often created phallus-shaped or had some other sexual allusion behind them, and yet they always remained strongly attached to the abstract world. West described some of the art pieces that he’d made to his friend, poet Reinhard Priessnitz, and he coined the original German name for them – Passstücke. Later, the artist sought an adequate English translation, and had to choose between Fitting Piece and Adaptive, preferring the translation and settling on the latter term. These works represented a truce between performance and art object and reflected the artist’s early admiration for the all-white reliefs and paintings of Piero Manzoni and Robert Ryman. With, of course, one big difference, they were created with the intention to be worn, carried, held, or simply touched by the viewers, giving his practice a true interactive dimension. Much of this later work was developed from ideas implicit in the Adaptives. The artist would sometimes invite others to apply paint or collage to their white surfaces. Before he even noticed, he was creating objects too big to handle, entering the world of “legitimate sculpture”. But even these continued to grow, eventually evolving into considerably larger papier-mâché and cardboard works whose fragmentary shapes and distressed surfaces had an ancient mien, as if they had survived the vicissitudes of time. Then he started making larger, hilariously bulbous, vibrantly colored papier-mâché pieces, something that West is arguably best known for. The possibilities of the found furniture incorporated in some of the Adaptives came to be in the center of his focus in the early 1980s, as he was making spindly chairs and divans out of rebar that parodied elegant furniture while being quite elegant and surprisingly comfortable themselves. His ambition slowly grew. So did his installations, where he now created combinations of sculptures, furniture, paintings, and even works made by other artists. In the late ‘90s, West’s focus turned to lacquered aluminum works, some of them inspired by the shapes of Adaptives. Apart from their appeal, they were o meant for lying and sitting, incorporating the basics of furniture. Despite his desire to remain close to a trash aesthetic (West destroyed any pieces that his friends had the carelessness to describe as beautiful), the work he made towards the end of the 1990s is more refined. Rough forms become streamlined, colours more saturated and convivial, as with “Knotzen” (2002): a trio of hard metal sculptures that look deceptively like brightly painted beanbag chairs. The “Sisyphos” sculptures are amorphous masses of papier-mâché, Styrofoam, and cardboard, expressively painted with lacquer and acrylic. They are named after the mythical first king of Ephyra, who deceived and plotted against others in order to advance his own power and prestige. Zeus punished Sisyphos for his hubris by forcing him to repeatedly roll a heavy boulder up a steep hill, only to have the rock tumble back down just as he reached the top.