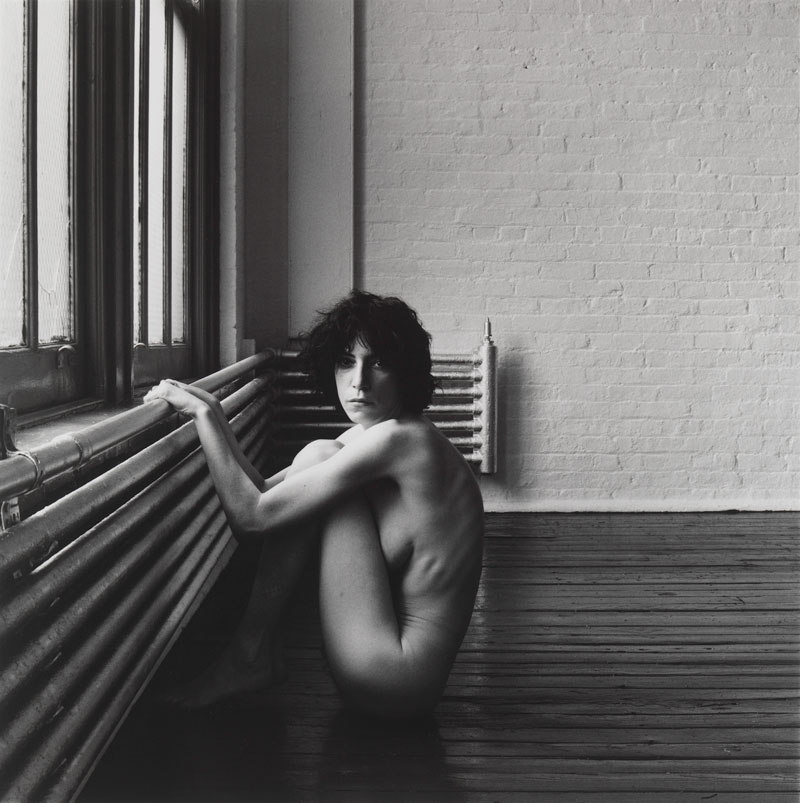

PHOTO:Implicit Tensions -Mapplethorpe Now,Part I

In the thirty years since his death, Robert Mapplethorpe has become a cultural icon. One of the most critically acclaimed and controversial American artists of the late 20th Century, Mapplethorpe is widely known for daring imagery that deliberately transgresses social mores, and for the censorship debates that transpired around his work in the United States during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Yet the driving force behind his artistic ethos was an obsession with perfection that he brought to bear on his approach to each of his subjects. “It’s the way I see things” he said in 1988. “Whether I see a body or a flower, it’s my eye” (Part II).

In the thirty years since his death, Robert Mapplethorpe has become a cultural icon. One of the most critically acclaimed and controversial American artists of the late 20th Century, Mapplethorpe is widely known for daring imagery that deliberately transgresses social mores, and for the censorship debates that transpired around his work in the United States during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Yet the driving force behind his artistic ethos was an obsession with perfection that he brought to bear on his approach to each of his subjects. “It’s the way I see things” he said in 1988. “Whether I see a body or a flower, it’s my eye” (Part II).

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Archive

Thirty years after his death, the yearlong exhibition “Implicit Tensions: Mapplethorpe Now” at Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum is conceived in two sequential parts and honors the work and legacy of Robert Mapplethorpe.Within Mapplethorpe’s body of work, a consistent, rigorously formal approach produced images with starkly different content. The artist summarized his intent in an interview: “My interest was to open people’s eyes, get them to realize anything can be acceptable. It’s not what it is, it’s the way it’s photographed”. Most famously, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Mapplethorpe produced three distinct series of photographs, each consisting of thirteen gelatin silver prints. He named the series—which feature S&M portraits, floral still lifes, and black male nudes—the X, Y, and Z Portfolios, respectively, to emphasize their formal continuity. In 1972, Mapplethorpe met the art collector and former curator Sam Wagstaff. Wagstaff gave the artist a Hasselblad medium-format camera for Christmas that year, which soon supplanted the Polaroid that curator John McKendry of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, had given Mapplethorpe the year prior. Both men played an essential role in the artist’s education and connected him with cultural figures in New York, some of whom became Mapplethorpe’s subjects. In the mid-1970s, working with individuals or duos posed full-figure within environmental settings, the artist produced several portraits that experimented with the symmetry and geometry of the Hasselblad’s perfectly square-format images. In one work, painter David Hockney and curator Henry Geldzahler lounge on a bench in Fire Island, their figures framed by the worn boardwalks and vertical wood paneling characteristic of the island’s architecture. In another, composer Philip Glass and director Robert Wilson assume similar poses in adjacent chairs. Yet the composition of the photograph, bisected by a vertical detail in the background, emphasizes their individual demeanors. Such works are distinct from Mapplethorpe’s later, more stylized artist portraits, which feature close-ups of his subjects’ faces. It has often been said that Mapplethorpe was his own favorite subject. The artist photographed himself consistently throughout his life, from his earliest experiments with a Polaroid camera made while living in New York’s Chelsea Hotel to the formal self-portraits he created in his studio shortly before his death. Mapplethorpe was a master of cultivating his own image and often used self-portraiture as a strategy, exploring various modes of self-presentation. In these works from 1980 and ’81, the artist embodies a range of possible gender expressions, including the surly hypermasculinity of a leather-jacketed bad boy and a highly feminine look featuring makeup, feathered hair, and a fur stole. Mapplethorpe’s ability to shift fluidly among such presentations speaks to his understanding that gender is socially constructed. Throughout his artistic career, Mapplethorpe utilized the genre of self-portraiture to experiment with self-image and explore notions of identity. “For me,” Mapplethorpe said, “S&M means sex and magic, not sadomasochism”. The artist’s photographs of men who participated in same-sex S&M subcultures of New York during the 1970s and ’80s are often considered to be near-documentary portrayals, but they nonetheless share the carefully crafted poses and rigorous formal choices characteristic of Mapplethorpe’s other compositions. While many of Mapplethorpe’s photographs are suffused with either overt or latent homoeroticism, his work’s relationship to the culture of gay liberation in the 1970s can be understood more broadly. Mapplethorpe’s considered use of brazen sexual openness was not only an expression of his own identity but also an artistic strategy. In July, the second part of this yearlong exhibition program will open in these galleries, exploring Mapplethorpe’s complex legacy in the field of contemporary art. A focused selection of his photographs will be on view alongside works by artists in the Guggenheim’s collection, including Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Lyle Ashton Harris, Glenn Ligon, Zanele Muholi, Catherine Opie, and Paul Mpagi Sepuya.

Info: Curator: Lauren Hinkson and Susan Thompson, Assistant Curator: Levi Prombaum, Duration: 25/1-10/7/2019 & 24/7/19-5/1/2020, Days & Hours: Mon, Wed-Fri & Sun 10:00-17:30, Tue & Sat 10:00-20:00, www.guggenheim.org