TRACES: Olafur Eliasson

Today is the occasion to bear in mind a noted member of the Social Practice movement, Olafur Eliasson (5/2/1967- ), who injects his work with a universal conscience that catapults art outside of its normal confines and challenges the way we inhabit the world. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind a noted member of the Social Practice movement, Olafur Eliasson (5/2/1967- ), who injects his work with a universal conscience that catapults art outside of its normal confines and challenges the way we inhabit the world. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Efi Michalarou

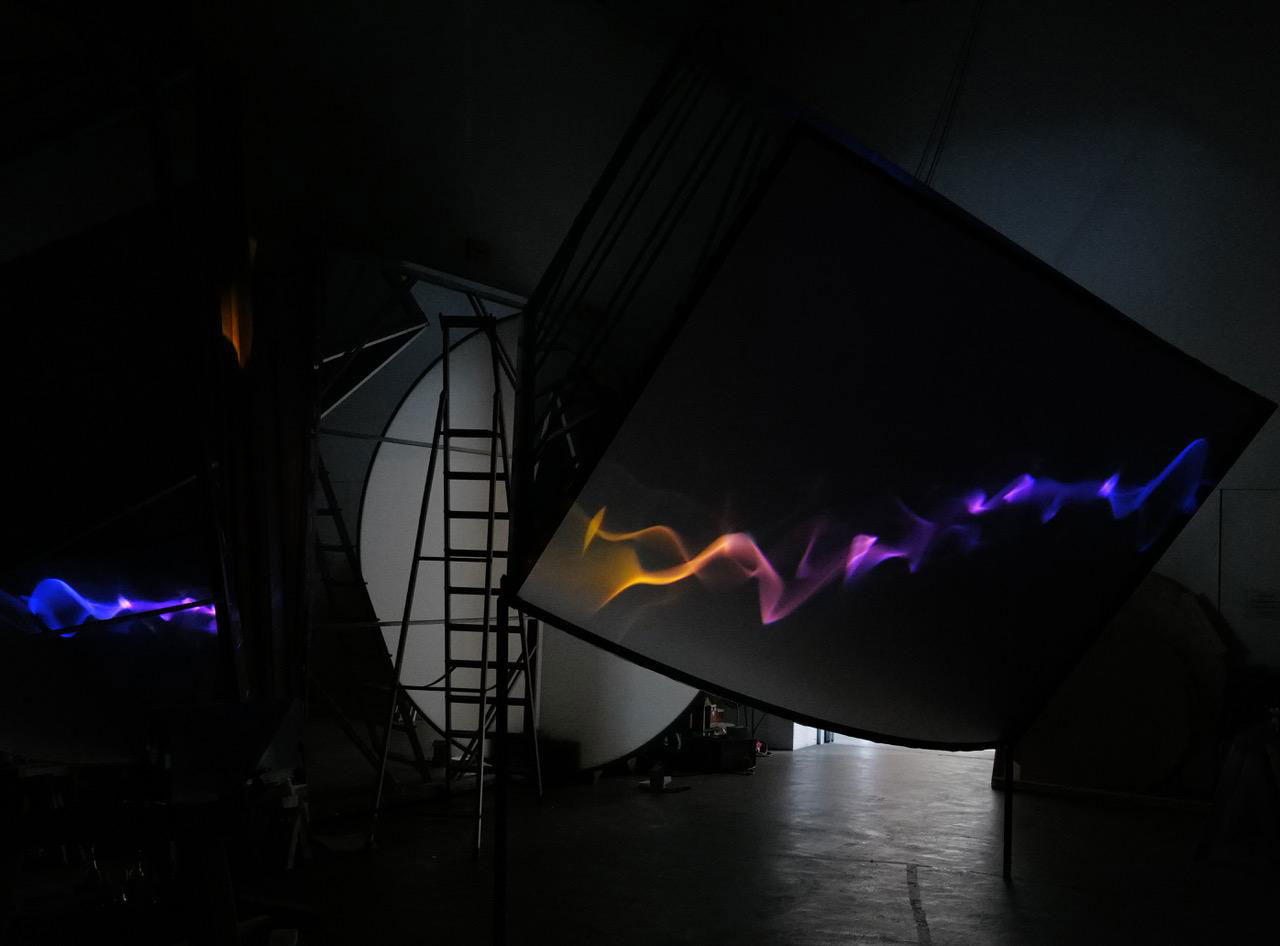

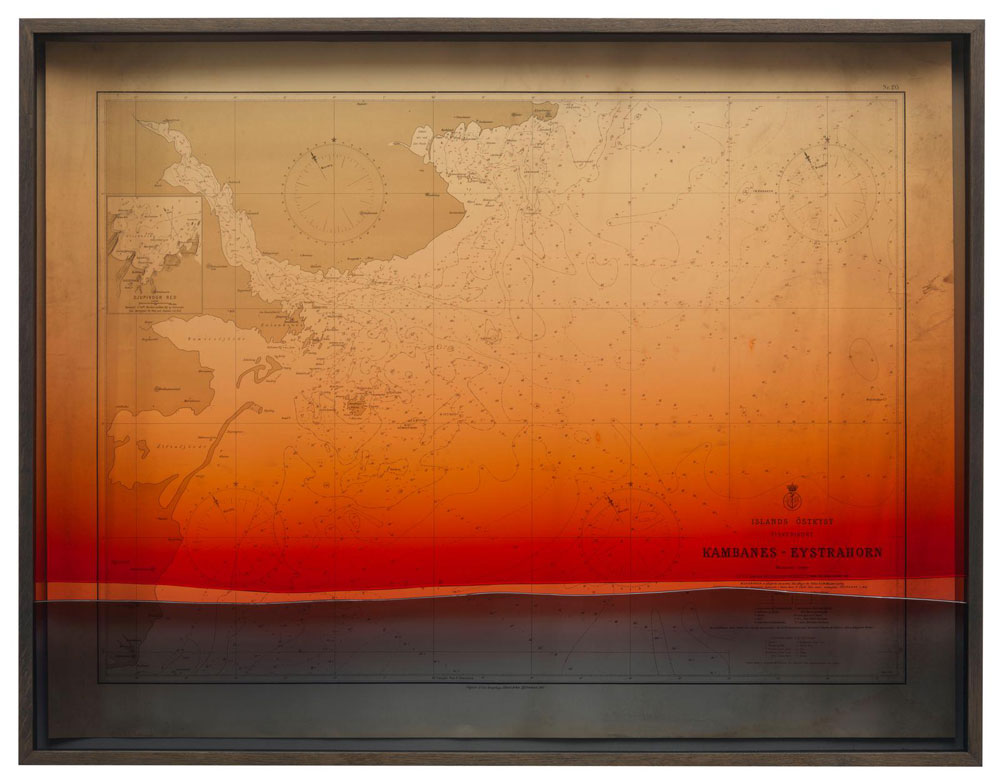

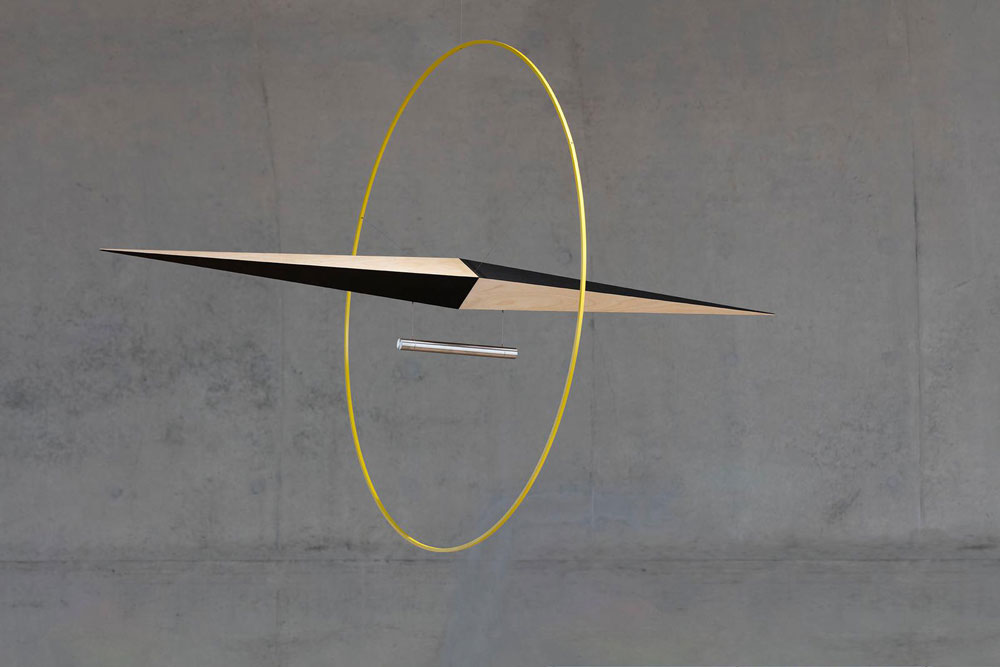

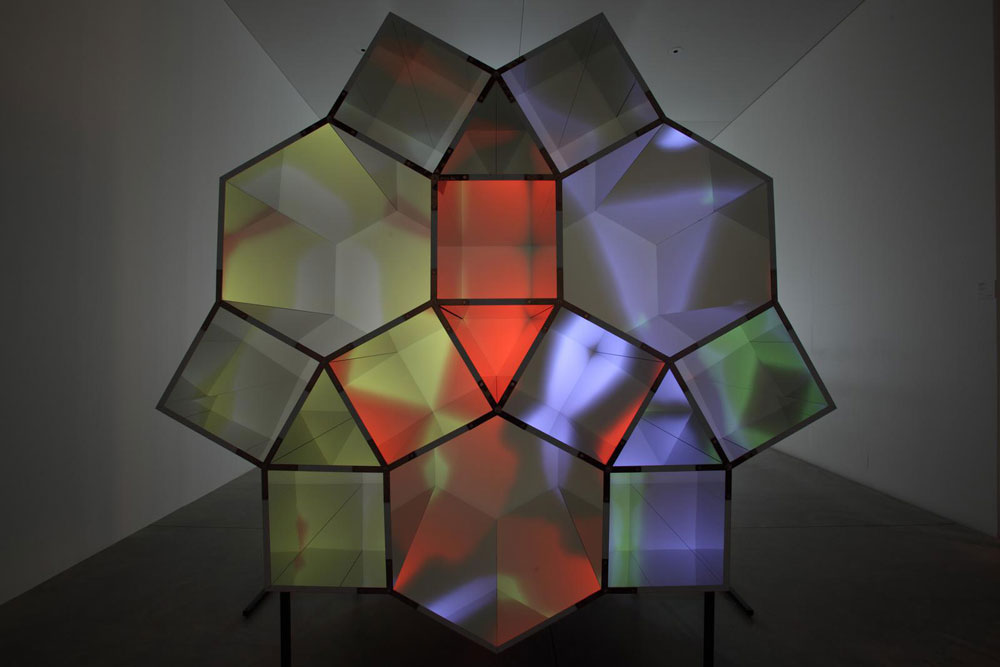

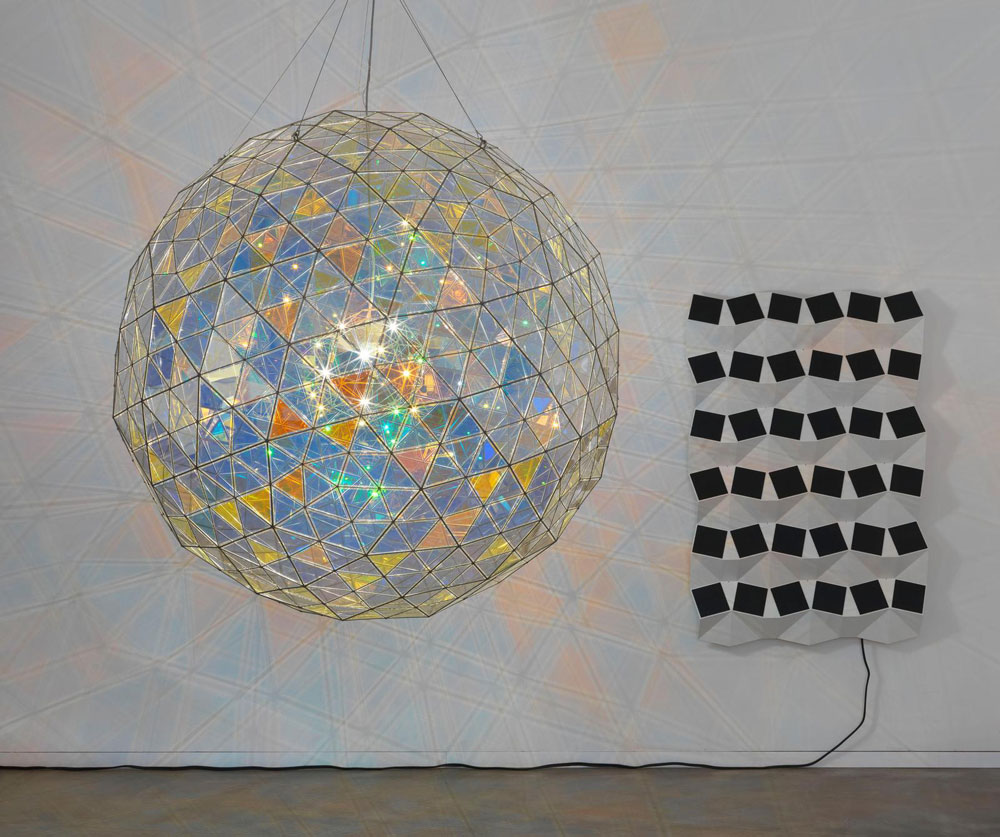

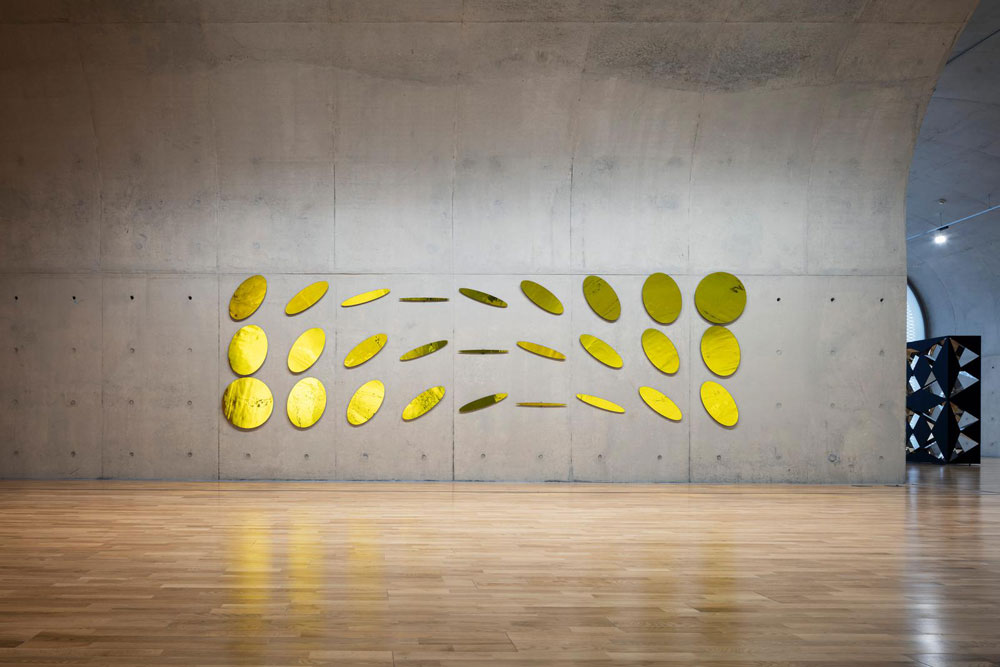

Olafur Eliasson was born in Copenhagen, Denmark in 5/221967, a year after his parents immigrated to the city from Iceland. His father’s family was from Reykjavík, Iceland’s capital, where they were part of a small artistic community. Eliasson’s grandmother was a photographer and his grandfather, who abandoned his family when Elías was young, was a publisher of avant-garde literature. Eliasson’s own parents divorced when he was four. During his infrequent trips to visit his fatherin Iceland, Eliasson began making drawings as a way to impress him. By the time he was 14 he could draw every bone in the human body, and at 15, he had his first exhibition splaying several landscape paintings at an alternative art space in Denmark. 1987 would become a turning point in Eliasson’s life. During the tumultuous year, his grandfather killed himself and his father was hospitalized for alcoholism, requiring Olafur to move to Iceland in order to care for his two-year-old half sister. Eliasson decided to apply to art school, and was duly accepted to the Royal Danish Academy of Art. “I would be lying if I said there wasn’t an element of escapism in my interest in art as a teenager” he said. “Making no sense seemed more attractive to me than making sense. Applying to art school was a lovely way for me to disconnect. Once I got there, though, I realized that art is about connecting. Instead of stepping out of the world, I was stepping right into the heart of it. This was a revelation for me. I thought it was only about being a good artist so that my father would like me. But it was more about shaping the world”. This notion of art as being a crucial means for turning thinking into doing within the world would lay the foundation for Eliasson’s eventual foray into Social Practice, an art medium focused on engagement through human interaction and social discourse. During his time at the art academy Eliasson was given a travel budget, and in 1990 he moved to New York where he worked for a period as a studio assistant for the Minimalist painter, Christian Eckart. During this time he also became a voracious reader and immersed himself in philosophy and scientific theories. He became especially intrigued with natural science and phenomenological philosophy, and its emphasis on an individual’s experience of reality. In 1995, he moved to Berlin and founded Studio Olafur Eliasson, which today comprises more than one hundred team members, including craftsmen, architects, archivists, researchers, administrators, cooks, programmers, art historians, and specialised technicians. In 1996 Eliasson started working with architect and geometry expert Einar Thorsteinn to create pieces such as “8900054” a stainless steel dome that appeared to be growing directly from the ground. The piece caused viewers to reflect upon things that are in constant development deep beneath ordinary surfaces. In 1998 for “Green River” Uranine, a water-soluble dye used to test ocean currents, was poured into rivers in urban and rural settings, turning the rivers green. Carried along by the currents, the dye radically changed the appearance of the rivers and their surroundings. Eliasson has carried out this unannounced intervention in six different locations: Bremen, Germany, 1998; Moss, Norway, 1998; The Northern Fjallabak Route, Iceland, 1998; Los Angeles, 1999; Stockholm, 2000; and Tokyo, 2001. Response to the intervention varied greatly depending on the location. In 1997 Eliasson was asked to contribute to the Danish pavilion at the São Paulo Biennial where he met Danish art historian and pavilion curator Marianne Krogh Jensen. The two connected over an altruistic desire to help those less fortunate. After marrying in 2003 they adopted two children from Ethiopia, a son in 2003 and a daughter in 2006. Starting in the early 2000s and with the help of his innovative studio collaborators, Eliasson began thinking of his socially engaged art as a means to affect change on a global scale. From 2009 to 2014, he imparted these philosophies as a professor at the Berlin University of the Arts. In 2012, he created “Little Suns”, portable solar lamps, which allow impoverished communities without access to electricity the ability to see in the dark. He also used proceeds from the sale of his art to establish, along with his wife, “121Ethiopia,” a foundation that funds African orphanages. A global artist concerned with the welfare of the world, today Eliasson travels the globe discussing how art can have a positive impact on humanity’s future. And while Eliasson’s art takes him all over the world, he often brings his family along in his travels, determined not to make the same mistakes his own father made with him. In 2014, along with architect Sebastian Behmann, Eliasson established an architectural counterpoint to Studio Olafur Eliasson called Studio Other Spaces, which focuses on interdisciplinary and experimental building projects and works in public spaces.The same year, “Riverbed“ filled an entire wing of Denmark’s Louisiana Museum of Modern Art with stones and water, emulating a river in a rocky landscape. “Verklighetsmaskiner” (Reality machines), at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 2015, became the museum’s most visited show by a living artist. In 2016, Eliasson created a series of interventions for the palace and gardens of Versailles and mounted two large-scale exhibitions: at Long Museum, Shanghai, and at Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul. “Green light-An artistic workshop”, created in collaboration with TBA21 (Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary), offers a response to the challenges of mass displacement and migration.

Olafur Eliasson was born in Copenhagen, Denmark in 5/221967, a year after his parents immigrated to the city from Iceland. His father’s family was from Reykjavík, Iceland’s capital, where they were part of a small artistic community. Eliasson’s grandmother was a photographer and his grandfather, who abandoned his family when Elías was young, was a publisher of avant-garde literature. Eliasson’s own parents divorced when he was four. During his infrequent trips to visit his fatherin Iceland, Eliasson began making drawings as a way to impress him. By the time he was 14 he could draw every bone in the human body, and at 15, he had his first exhibition splaying several landscape paintings at an alternative art space in Denmark. 1987 would become a turning point in Eliasson’s life. During the tumultuous year, his grandfather killed himself and his father was hospitalized for alcoholism, requiring Olafur to move to Iceland in order to care for his two-year-old half sister. Eliasson decided to apply to art school, and was duly accepted to the Royal Danish Academy of Art. “I would be lying if I said there wasn’t an element of escapism in my interest in art as a teenager” he said. “Making no sense seemed more attractive to me than making sense. Applying to art school was a lovely way for me to disconnect. Once I got there, though, I realized that art is about connecting. Instead of stepping out of the world, I was stepping right into the heart of it. This was a revelation for me. I thought it was only about being a good artist so that my father would like me. But it was more about shaping the world”. This notion of art as being a crucial means for turning thinking into doing within the world would lay the foundation for Eliasson’s eventual foray into Social Practice, an art medium focused on engagement through human interaction and social discourse. During his time at the art academy Eliasson was given a travel budget, and in 1990 he moved to New York where he worked for a period as a studio assistant for the Minimalist painter, Christian Eckart. During this time he also became a voracious reader and immersed himself in philosophy and scientific theories. He became especially intrigued with natural science and phenomenological philosophy, and its emphasis on an individual’s experience of reality. In 1995, he moved to Berlin and founded Studio Olafur Eliasson, which today comprises more than one hundred team members, including craftsmen, architects, archivists, researchers, administrators, cooks, programmers, art historians, and specialised technicians. In 1996 Eliasson started working with architect and geometry expert Einar Thorsteinn to create pieces such as “8900054” a stainless steel dome that appeared to be growing directly from the ground. The piece caused viewers to reflect upon things that are in constant development deep beneath ordinary surfaces. In 1998 for “Green River” Uranine, a water-soluble dye used to test ocean currents, was poured into rivers in urban and rural settings, turning the rivers green. Carried along by the currents, the dye radically changed the appearance of the rivers and their surroundings. Eliasson has carried out this unannounced intervention in six different locations: Bremen, Germany, 1998; Moss, Norway, 1998; The Northern Fjallabak Route, Iceland, 1998; Los Angeles, 1999; Stockholm, 2000; and Tokyo, 2001. Response to the intervention varied greatly depending on the location. In 1997 Eliasson was asked to contribute to the Danish pavilion at the São Paulo Biennial where he met Danish art historian and pavilion curator Marianne Krogh Jensen. The two connected over an altruistic desire to help those less fortunate. After marrying in 2003 they adopted two children from Ethiopia, a son in 2003 and a daughter in 2006. Starting in the early 2000s and with the help of his innovative studio collaborators, Eliasson began thinking of his socially engaged art as a means to affect change on a global scale. From 2009 to 2014, he imparted these philosophies as a professor at the Berlin University of the Arts. In 2012, he created “Little Suns”, portable solar lamps, which allow impoverished communities without access to electricity the ability to see in the dark. He also used proceeds from the sale of his art to establish, along with his wife, “121Ethiopia,” a foundation that funds African orphanages. A global artist concerned with the welfare of the world, today Eliasson travels the globe discussing how art can have a positive impact on humanity’s future. And while Eliasson’s art takes him all over the world, he often brings his family along in his travels, determined not to make the same mistakes his own father made with him. In 2014, along with architect Sebastian Behmann, Eliasson established an architectural counterpoint to Studio Olafur Eliasson called Studio Other Spaces, which focuses on interdisciplinary and experimental building projects and works in public spaces.The same year, “Riverbed“ filled an entire wing of Denmark’s Louisiana Museum of Modern Art with stones and water, emulating a river in a rocky landscape. “Verklighetsmaskiner” (Reality machines), at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 2015, became the museum’s most visited show by a living artist. In 2016, Eliasson created a series of interventions for the palace and gardens of Versailles and mounted two large-scale exhibitions: at Long Museum, Shanghai, and at Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul. “Green light-An artistic workshop”, created in collaboration with TBA21 (Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary), offers a response to the challenges of mass displacement and migration.