ART-PRESENTATION: Chinese Whispers,Part I

A business journalist, entrepreneur, and Swiss ambassador to China, North Korea, and Mongolia (1995–1998), Uli Sigg had the chance to take a look behind the scenes of the enormous social and economic developments dedicated to both tradition and the future, as China’s vision of a New Silk Road shows. Sigg has furthered several international careers such as Ai Weiwei’s and donated 1.510 works of his collection in the form of the M+ Sigg Collection to the newly founded M+ Museum for visual culture, in Hong Kong, which was designed by Herzog & de Meuron (Part II).

A business journalist, entrepreneur, and Swiss ambassador to China, North Korea, and Mongolia (1995–1998), Uli Sigg had the chance to take a look behind the scenes of the enormous social and economic developments dedicated to both tradition and the future, as China’s vision of a New Silk Road shows. Sigg has furthered several international careers such as Ai Weiwei’s and donated 1.510 works of his collection in the form of the M+ Sigg Collection to the newly founded M+ Museum for visual culture, in Hong Kong, which was designed by Herzog & de Meuron (Part II).

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: MAK Archive

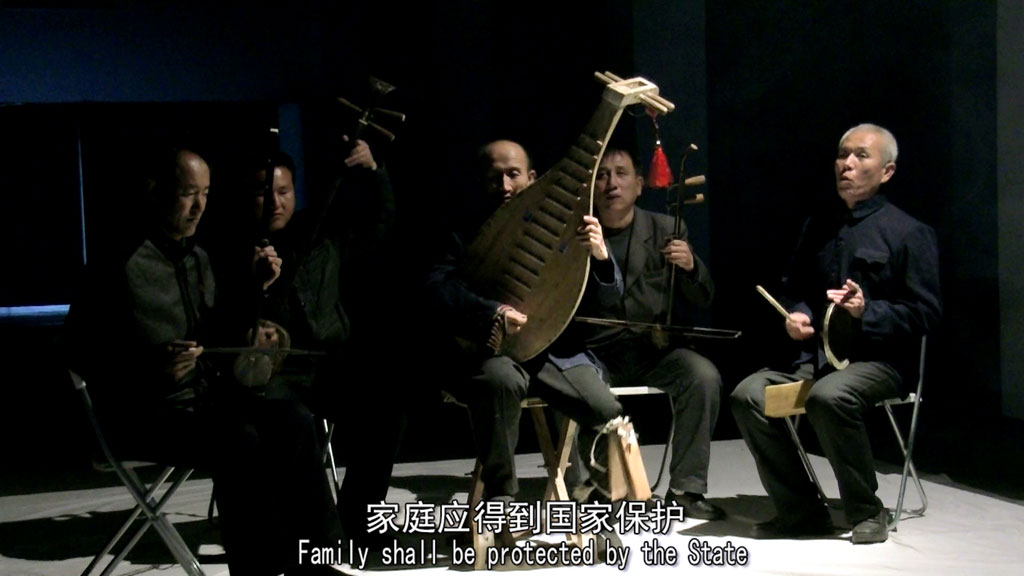

A comprehensive picture of contemporary Chinese art and its aesthetic as well as iconographic references is presented by the exhibition “Chinese Whispers: Recent Art from the Sigg Collection” at MAK|Vienna. The exhibition focuses on objects from Uli Sigg’s Swiss private collection, which he has continuously expanded. With techniques such as calligraphy, painting, photography, sculpture, installation, and video, the presented objects open up a wide spectrum of works ranging from traditional analog to digital production. The title CHINESE WHISPERS refers to the eponymous children’s game in which messages are whispered secretly from one person to the next and distorted in content and meaning by the permanent repetition. This idea of reproduction and distortion can be seen as an ironic allusion to intercultural communication. Chinese contemporary art is a phenomenon without parallel. Even after the Cultural Revolution, the effects of Socialist Realism and restrictions due to censorship remain noticeable. Nonetheless, contemporary art in China has experienced a drastic change of direction since the increasing political openness in the 1980s. In no time a new generation of Chinese artists picked up contemporary trends from the West. The contents can often be seen as a reaction towards the political and social situation of the time. In his painting “My Beautiful Life” (1993-95), Wang Xingwei for example, chose an image composition referring to Edvard Munch’s icon-like painting “The Scream”. Wang Xingwei contrasts the painter’s loneliness in Munch’s self-portrait with a contemplative portrait of a couple on a bridge whose gaze ebbs away in a landscape contrasted by set pieces of modern consumption and progress. Given its hybrid capability, Chinese communism has adopted global capitalism. The People’s Republic of China today is regarded as the world’s economic powerhouse, pursuing global political goals. China’s investments in technology, science, and research imply control of the economy but also control of the people. With the slogan “Chinese Dream,” by now popular as part of the political ideology, Xi Jingping, General Secretary of the Communist Party of China, describes the role of the individual in society and national goals. This focus is, for example, addressed by artist Miao Ying in “Le Rêve Chinois” (2018), an installation of filtered wishes and images available on the internet in China. In a striking way, she illustrates the link between political marketing and the colorful advertising of luxury goods. The controversial role of the individual in a rapidly growing society and the boundaries between artistic, social, and political space can be experienced in quite a number of works in the exhibition. At the beginning of the 1950s, the term “New Man” was introduced by the communist regime in order to establish Marxism-Leninism and Maoism in society. The revolution, aimed at creating a new aesthetics by reconfiguring tradition and culture, is highlighted by Liu Ding in his collectively developed project also called “New Man” (2014). The aim was to suggest the wish to partake in a political vision to the individual. Shao Fan deals with the re-appropriation of history in “King Chair” (1997) and he combines elements of a piece of furniture from the Ming dynasty with contemporary design language. Ai Weiwei also examines the line between visual art and design in the reflection of history, like in his installation “Descending Light with A Missing Circle” (2017), which was specifically commissioned by the Sigg Collection. A monumental chandelier made of red crystal beads which appears to have fallen to the floor points to the decay of modern society. In the 20th century, the color red, in China traditionally a symbol of luck in all its conflictive facets, became the color of revolution, progress, and political power through the ideology of communism. As an example for exploring the cultural transfer between East and West, the work “The Death of Marat” (2011) by He Xiangyu can be seen in the exhibition. It shows a scene with Ai Weiwei and refers to the painting of the same title by Jacques-Louis David, an icon of the French Revolution. Xiangyu developed the idea for this work when Ai Weiwei was in prison in China and simultaneously Wen Jiabao, Chinese Premier at the time, paid a state visit to Germany. Mao Tongqiang’s collection “Archives” (2011-13) consists of approximately 1 800 documents from the archives of the department of Internal Security of a Chinese city, dated from 1949 to 1980. The presentation of the historical records reveals the individual’s social connections and his or her relationship to the state after the founding of the People’s Republic of China. The records document how archives or rather the collection of data are used to control people. In the MAK exhibition, the works from the Sigg Collection enter into a dialogue with historical objects from China from the MAK Asia Collection. Since its founding more than 150 years ago, the MAK has placed one of the focal points of the museum on Asian arts and crafts from China, Japan, and Korea. As early as around 1900, the museum was able to document the zeniths of Asian cultures. In 1907, a large part of the collection of the Trade Museum, which had been founded for economic-political reasons, went to today’s MAK. In fascinating confrontations, the historic object turns into a vision machine for the contemporary. For example, Shen Shaomin with her sculpture “Bonsai No. 19” (2015) addresses the eponymous art form cultivated in China: interfering with a plant’s growth is comparable to the ritual of foot binding, a symbol of oppression leading to irreparable deformations in girls and womens illustrated in the exhibition by Colorful Chinese shoes for bound feet (19th Century).

Info: MAK–Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / Contemporary Art, Stubenring 5, Vienna, duration: 30/1-26/5/19, Days & Hours: Tue 10:00-22:00, Wed-Sun 10:00-18:00, www.mak.at