ART PRESENTATION: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Part II

Following the waves of Minimalism and Conceptual art at the end of the 20th Century, Jean-Michel Basquiat stood out as a figurative painter. At that moment figuration was a discredited genre and seemed spent. However, from the very start, Basquiat set himself the challenge of giving existence to the Black Figure – Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man”- in the social and cultural space (Part I).

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Fondation Louis Vuitton Archive

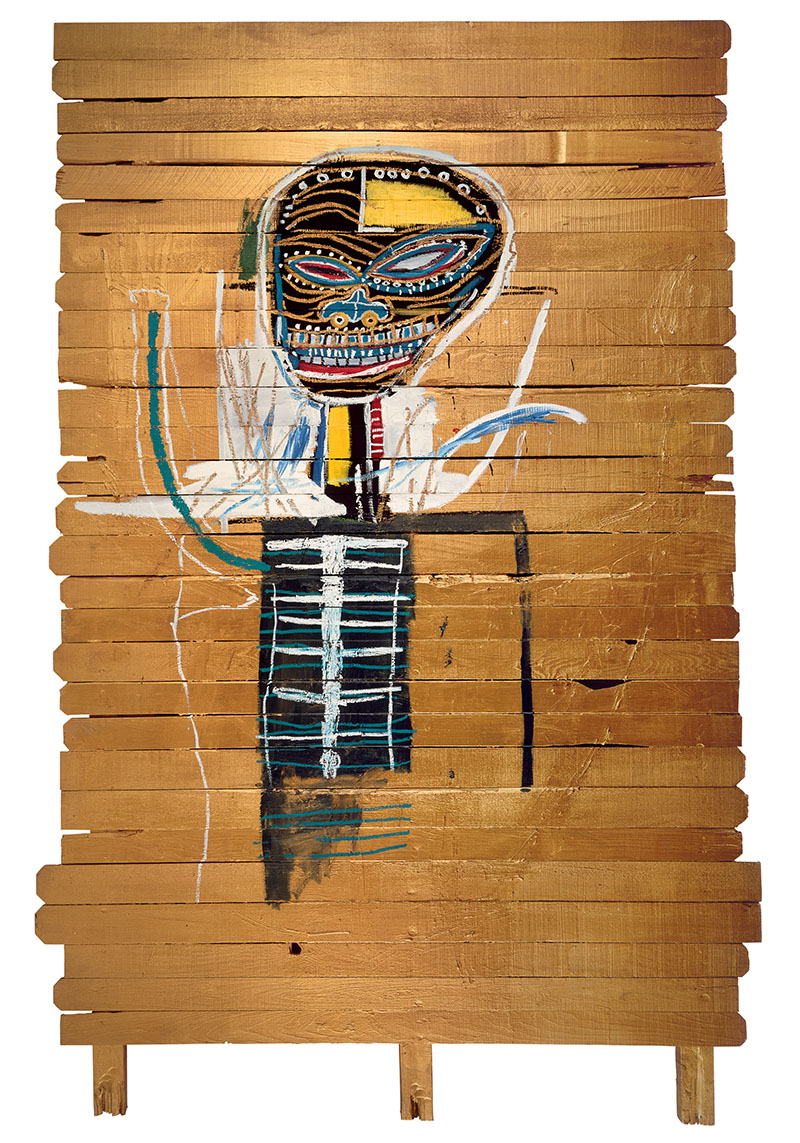

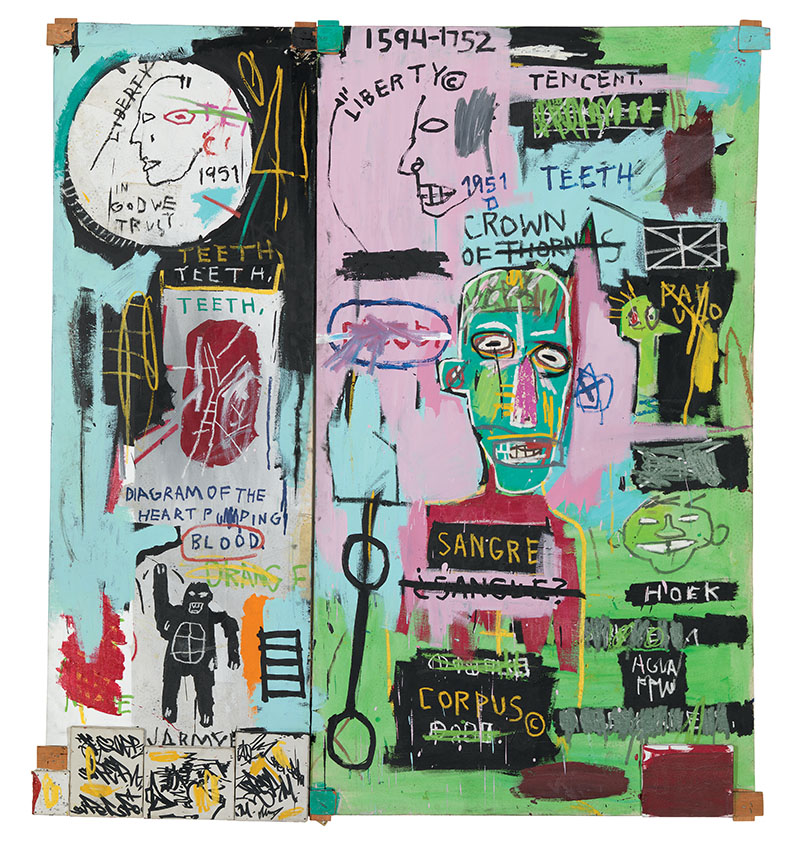

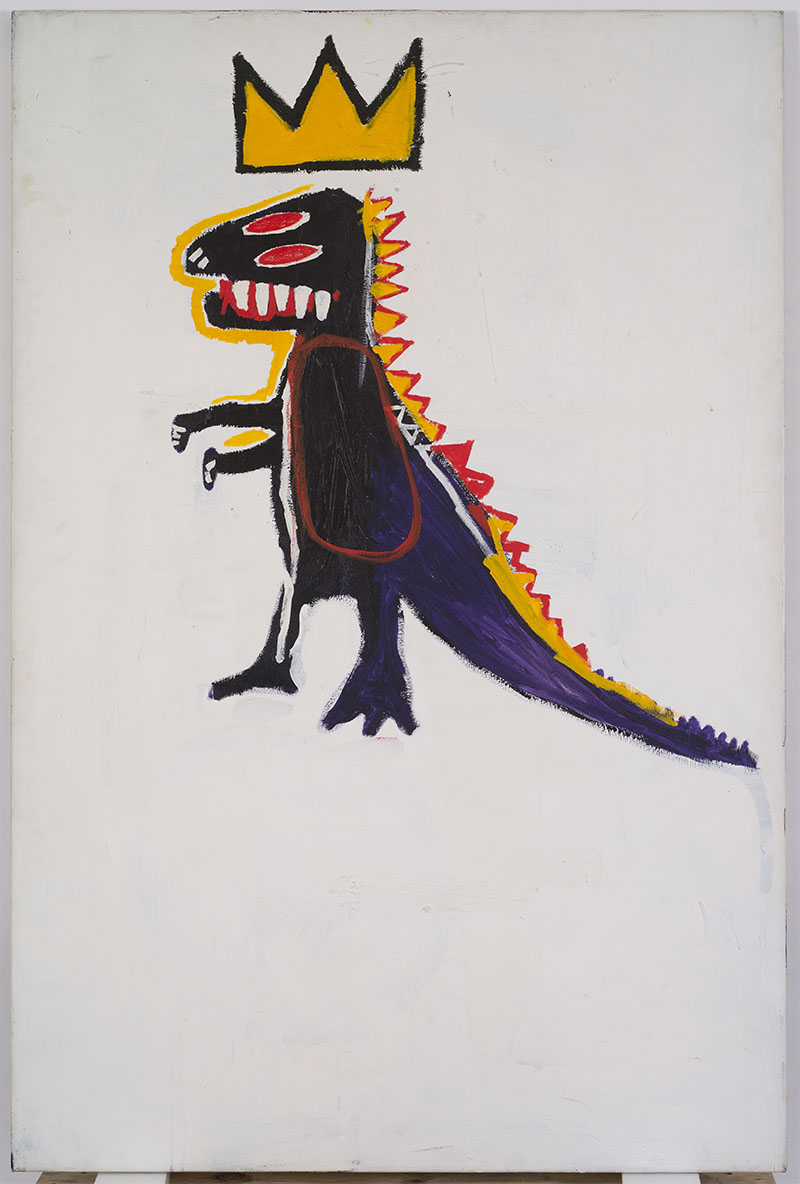

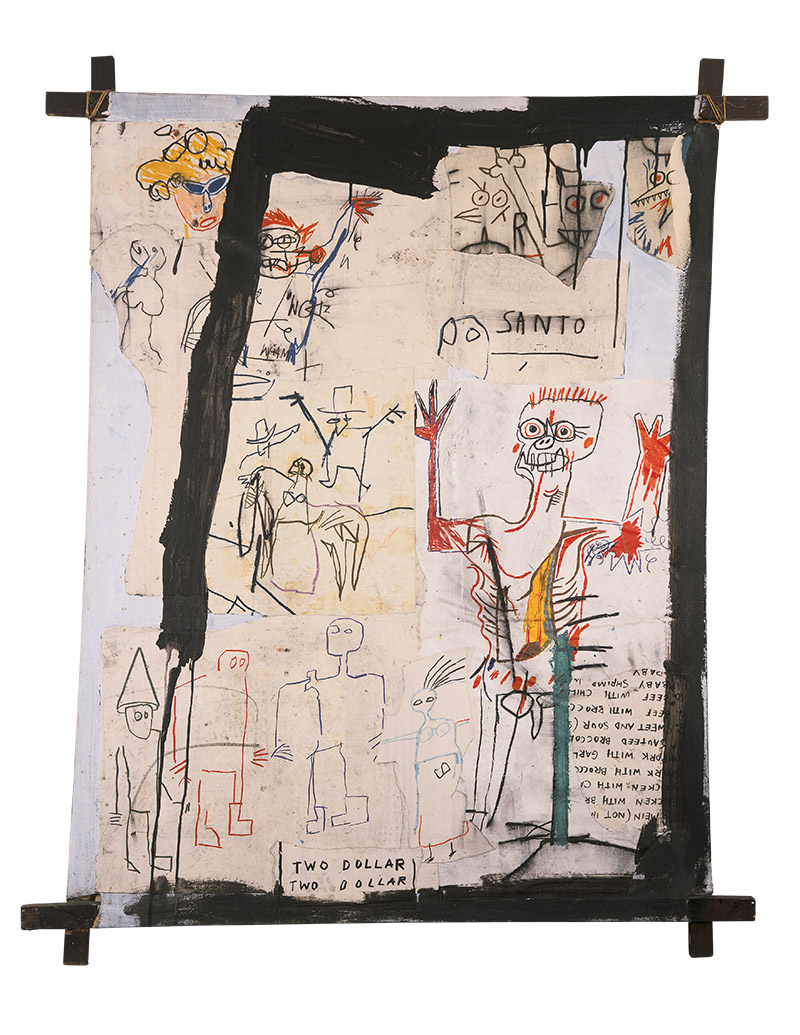

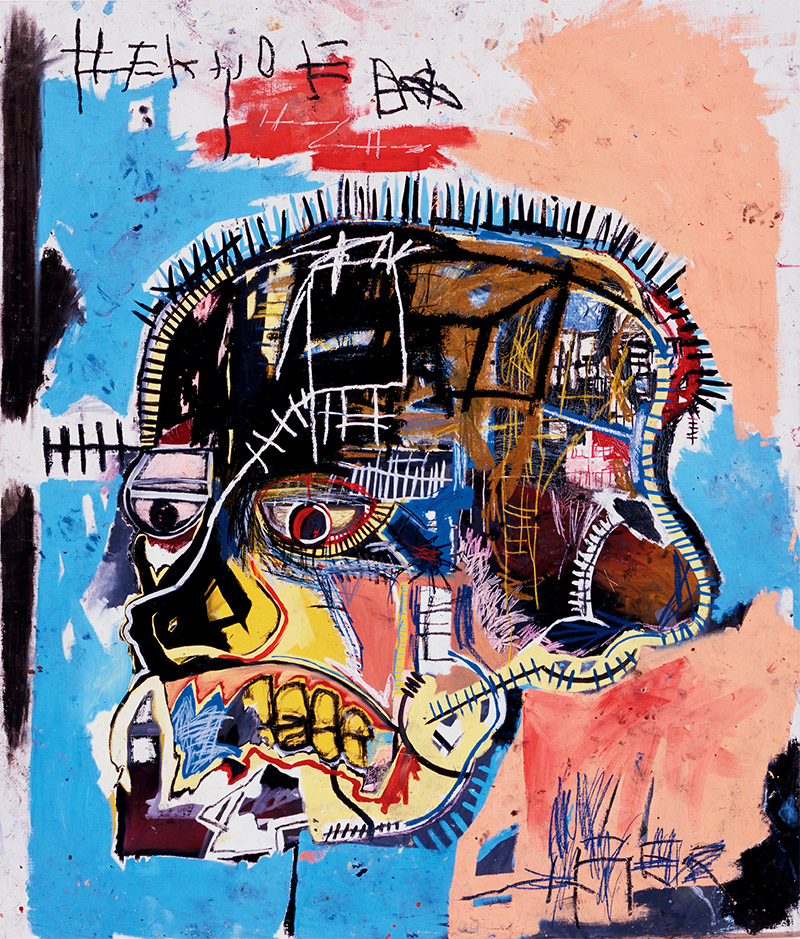

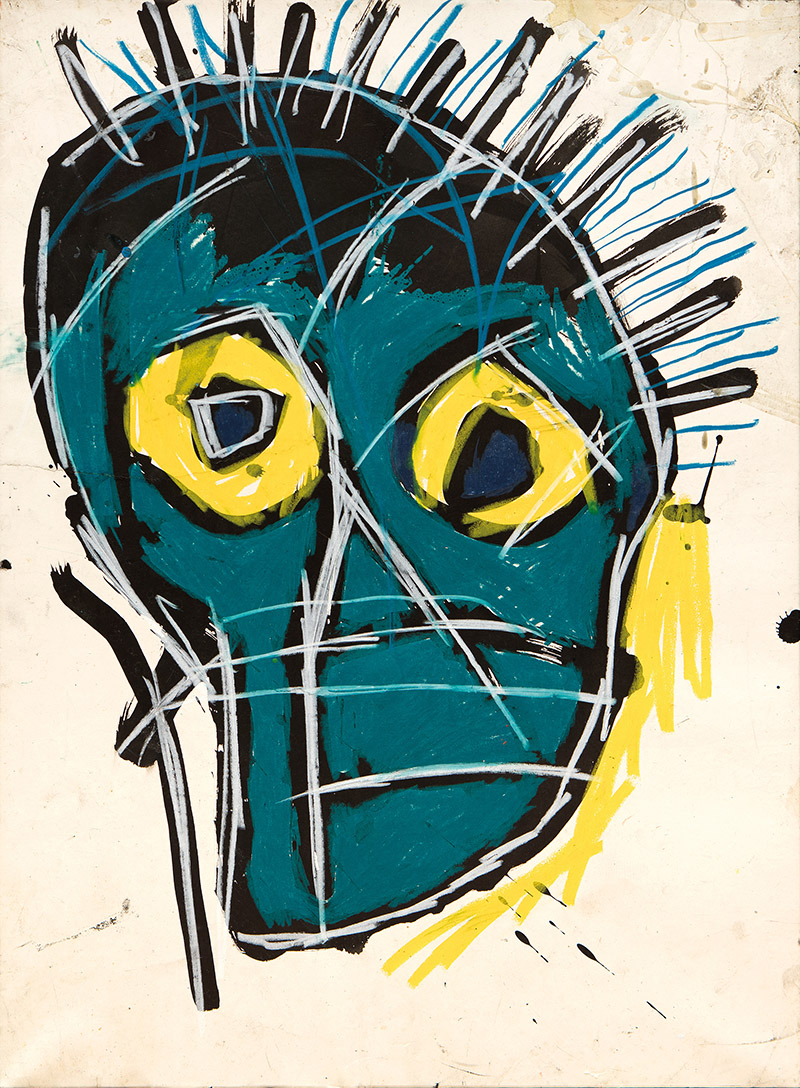

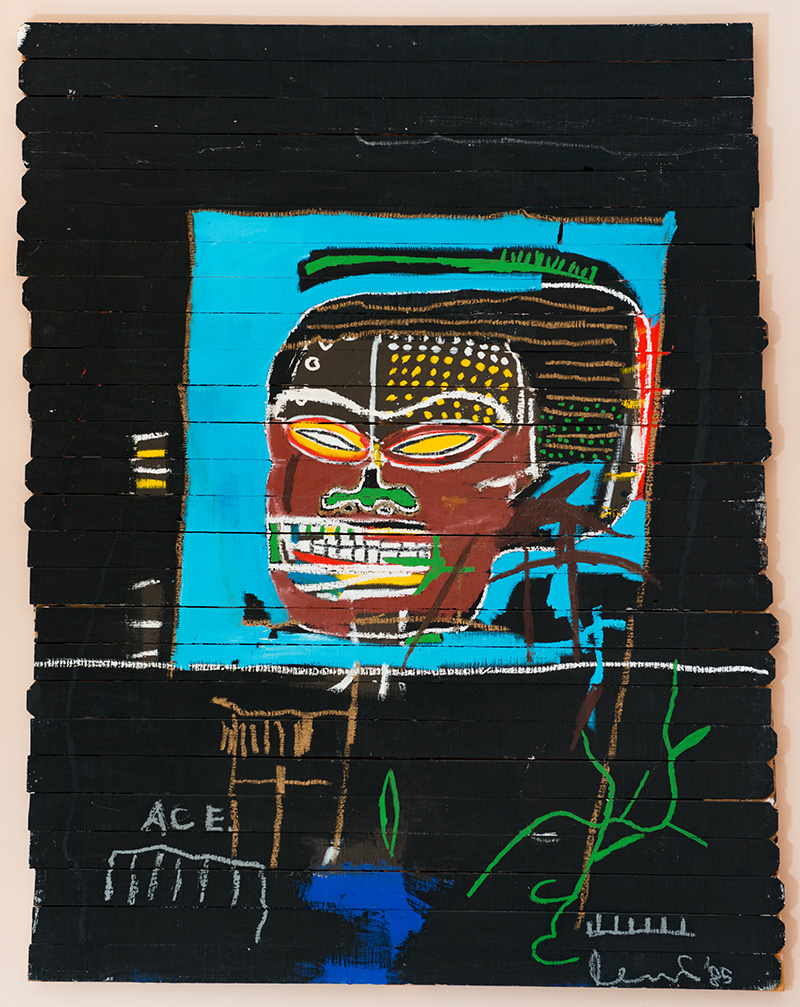

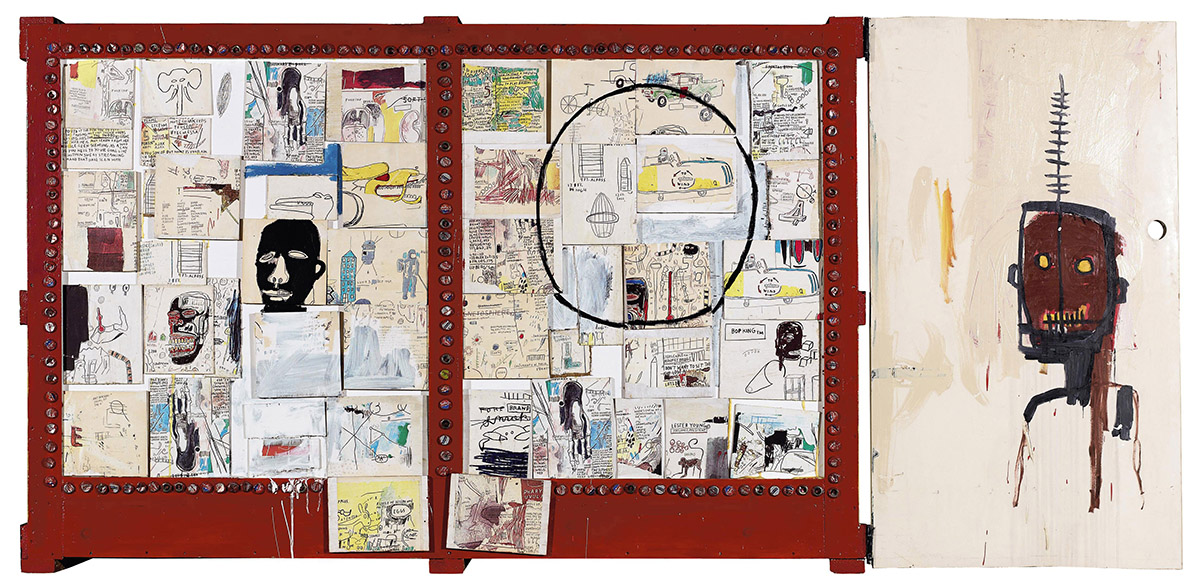

This mission became vital to Jean-Michel Basquiat following his painful recognition of the absence of Black men and women in the rooms and on the walls of the New York museums that he visited regularly with his mother (Brooklyn Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, MoMA). In fact, the eminently contemporary Basquiat could not have had such resonance in the future without such a true knowledge and understanding of the art of the past. With a natural instinct for openness, linked to his twin Haitian and Puerto Rican roots, Basquiat absorbed everything, like a sponge, mixing the lessons of the street with a repertoire of images, heroes, and symbols from a wide range of cultures. In the same way as the hip-hop culture that he helped to bring to the fore, he freely appropriated them: the Bible, Egypt, voodoo, African-American heroes, comic books mingled with Leonardo da Vinci, Matisse, Picasso, and so on, along with contemporary references. This mix gave rise to a completely new language to which he gave voice in collage and graffiti. His obsession with drawing provided a vehicle for his young body, a concentration of all energies, taut with a genuine rage to express urgently. His awareness of an almost Christ-like mission was another characteristic he shared with Schiele, as was an entrenched relationship with words. Before he was twenty, Basquiat was first a poet as part of SAMO©, expressing terse, dreamlike, and sometimes spiteful maxims on buildings. He was also a musician playing in some of New York’s most frenzied spaces at the end of the 1970s. His actions placed him in the most influential circles, gradually making him the first African-American artist to really be accepted visually and symbolically in the world of Western art. The exhibition “Jean-Michel Basquiat” at Fondation Louis Vuitton brings together some 120 works and it is structured around chronological and thematic groups spread over the Fondation’s four levels and eight galleries. The exhibition includes the most diverse and unorthodox supports used by the artist: canvas, paper, hoardings, doors, planks, objects, silkscreens, and photocopies, among others. The exhibition begins with “Untitled (Car Crash)” (1980), referring to the accident that marked the artist when he was a child, and concludes with “Riding with Death” (1988), created just before his passing. On Gallery 2, three monumental Heads (1981, 1982, 1983), are brought together here for the first time. Covering the years 1981 and 1982, the works focus on the theme of the Street, both studio and source of inspiration. Other the other works are: “Crowns (Peso Neto)” (1981), “Untitled (Blue Airplane)” (1981), the large figures of the Prophets and the striking portraits of La Hara and the black policeman in Irony of a Negro Policeman. The Gallery 4 opens with a set of drawings of “Heads” (1982), followed by a gallery of Basquiat’s “heroes,” boxers or fighters, referring to his own rebellion: “Untitled (Sugar Ray Robinson)” (1982), “St. Joe Louis Surrounded by Snakes” (1981), “Cassius Clay” (1982), and others. The inclusion of letters, figures, signs, and texts emphasize the complexity of his compositions, for example, in “Santo #1” (1982) and “Self-Portrait with Suzanne” (1982). On Gallery 5, the section “Heroes and Warriors” introduces a sequence of figures adorned with haloes, crowns, or crowns of thorns: Samson, in “Obnoxious Liberals” (1982), appears as a figure of emancipation, while “Price of Gasoline in the Third World” (1982) and “Slave Auction” (1982) make a direct reference to the exploitation of black bodies and the treatment of slaves. Other heroes who were crucial to Basquiat were musicians, above all the saxophonist Charlie Parker, whom he considered an alter ego. Grouped separately on Gallery 7 are six compositions in which various figures borrowed from history, art history, or Basquiat’s own environment are set on a grid/score that gives structure to the work: “Mona Lisa in Lye” (1983) and “Joe Louis in Napoleonic Stereotype Circa’44”, a tribute to the boxer whose always triumphant career took a blow in 1936 when he was defeated by a boxer representing Nazi Germany. On Gallery 9, two important groups of works are shown. The first places a related group, including “Gold Griot” (1984), around the monumental “Grillo” (1984), which abounds with allusions to different African cultures. The Black Figure, as a representation and reinterpretation of the diaspora, is omnipresent. The title Grillo (“cricket” in Spanish) refers to the griot of West Africa, a central figure in the transmission of family stories and community traditions. The last rooms (Galleries 10 and 11) contain the artist’s final works (1987-1988). A compelling presence in every respect is “Riding with Death”, shown in Paris for the first time.

Info: Head curator: Suzanne Pagé, Curators: Dieter Buchhart and Anna Karina Hofbauer, Assistant Curator: Lexie Jordan, Curator for the presentation in Paris: Olivier Michelon, AssistantCurator: Camila Souyri, Fondation Louis Vuitton, 8 Avenue du Mahatma Gandhi, Bois de Boulogne, Paris, Duration 3/10/18-14/1/19, Days & Hours: Mon & Wed-Thu 11:00-20:00, Fri-Sun 9:00-21:00, www.fondationlouisvuitton.fr