ART-PRESENTATION: Concrete Matters,Part II

In the mid-1940s, Art Movements in Argentina began to reinterpret and develop the European Concrete Art. These artists said that figurative, representational art tended to “Dampen the cognitive energy of man, distracting him from his own powers”. The concretists rejected the illusionism that artists had used over the centuries to create a three-dimensional pictorial space on the two-dimensional surface of the canvas. Instead, they proposed that people should be surrounded by real things, not illusions. Concrete art was the path forward, since it ”Accustoms man to a direct relationship with things and not with the fiction of things” (Part I).

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Moderna Museet Archive

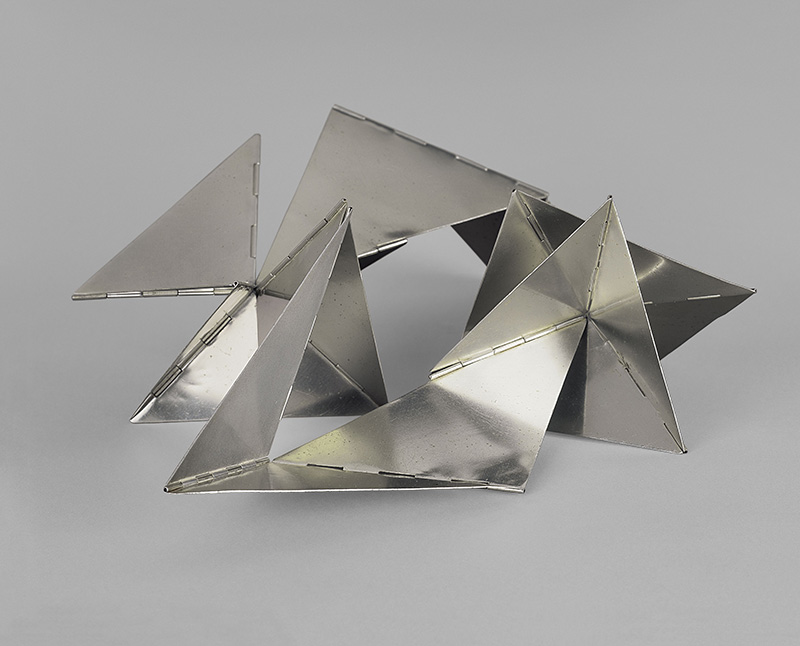

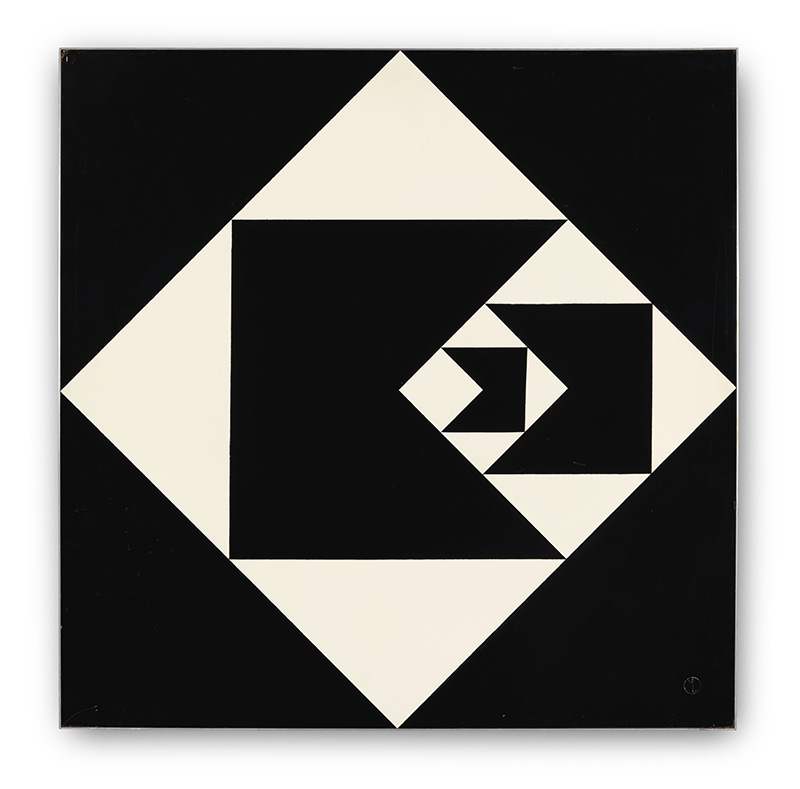

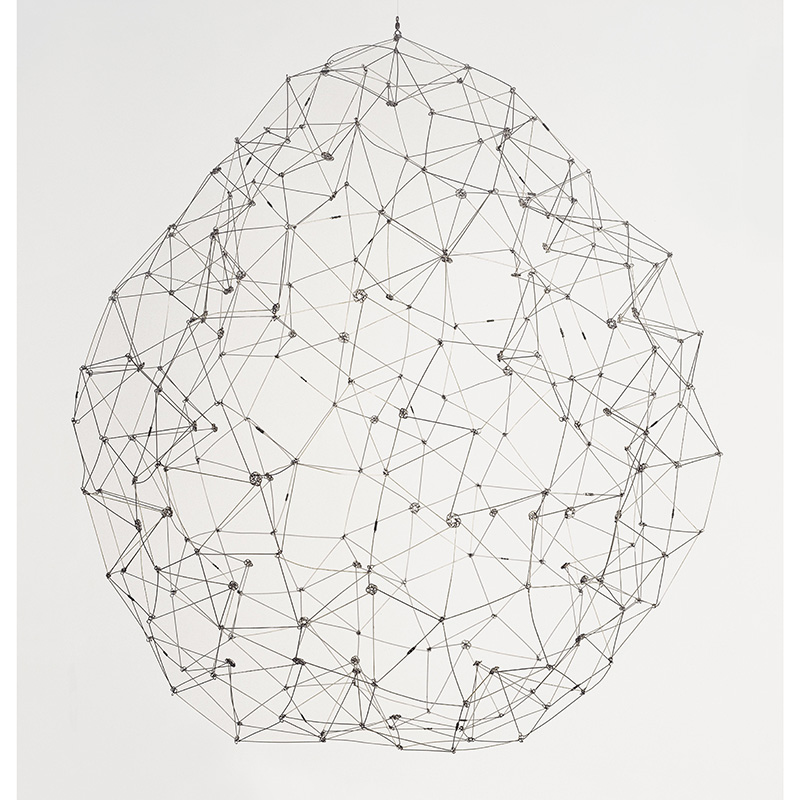

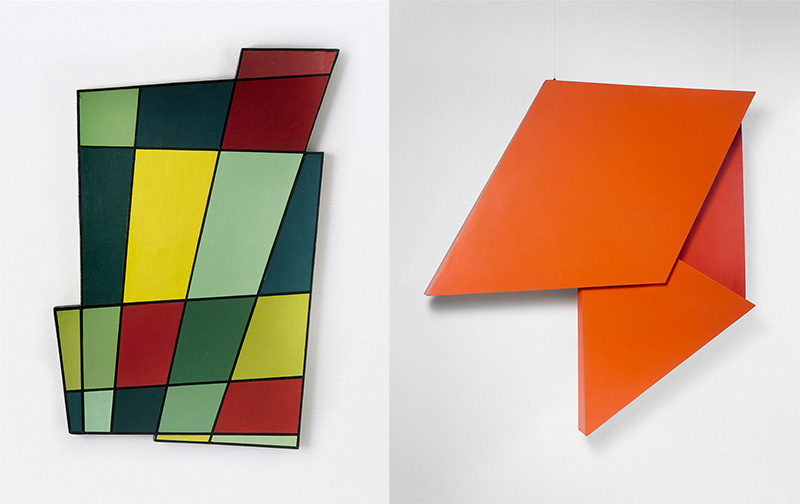

Joaquin Torres-Garcia is a pioneer of non-figurative art in Latin America, although he used symbols in his work, unlike Theo van Doesburg, with whom he made friends in Paris. After nearly 40 years in Europe and North America, he returned to Uruguay in 1934. The year after his return, he published the text “The School of the South”, in which he argues that an art school should be founded in Uruguay. Torres-Garcia stressed that art in the rapidly-modernised nation should be filled with content, created by the people. He encouraged his colleagues to have a global approach but without forgetting their local context. Torres-Garcia combined European constructivism with pre-Columbian art in his own constructive universalism. His compatriot Rhod Rothfuss moved to Buenos Aires in 1942, where he was to have considerable influence on the development of concrete art. Interest in concrete art began to grow in Argentina in the early 1940s. In 1944, the magazine Arturo was published. Tomás Maldonado and Gyula Kosice were among the contributors. Rhod Rothfuss wrote in Arturo that although abstract painting had liberated art from depicting reality like a camera, the rectangular format nevertheless adhered to the illusion of the painting as a window into another world. The solution was to give the canvas an irregular shape. This idea had a huge impact.In the mid-1940s, two central groups had established themselves. Asociación Arte Concreto-Invención (AACI) had a strongly political approach to art, rooted in Karl Marx’s dialectical materialism and emphasizing on action and change. Tomás Maldonado, Raúl Lozza , Juan Melé, and Juan Alberto Molenberg belonged to this group. Lozza and Molenberg rejected the frame entirely by connecting individual elements on the same plane parallel to the wall. The other group, Madí, included Gyula Kosice, Rhod Rothfuss and Carmelo Arden Quin. Madí had a more dada-inspired and playful approach, and experimented with irregularly-shaped canvases and three-dimensional objects. After the military junta seized power in Venezuela in 1948, many artists, including Jesús Rafael Soto left for Paris, where they joined Los Disidentes. This was an artist group that had been started by Alejandro Otero and others a few years earlier. Unlike many of his contemporary artists, Soto was not interested in mechanical movement but in human and eye movements. His works changed appearance as the viewers moved around them. Carlos Cruz-Diez also focused on the interaction between art and spectator. In his physiochromies, the colour changes depending on the viewer’s position. He also created interactive works where the audience could alter the position of components. Gego (Gertrud Louise Goldschmidt) fled to Venezuela from the Nazi regime in 1939. In the 1960s, she began using materials such as wire, paper and iron to create her three-dimensional drawings. Her wire installations put lines and shapes in direct relation to the space. The new capital Brasilia, inaugurated in 1960, was a manifestation of the radical social transformation of Brazil. This utopian project followed President Juscelino Kubitschek’s promise to make up for “50 years of development in five years”. But the artists were active mainly in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. Museu de Arte de São Paulo opened in 1947. The exhibitions featured artists such as Alexander Calder, Le Corbusier and Max Bill. While concrete art was losing its significance in Europe, Max Bill’s ideas were welcomed with open arms in South America. When Grupo Ruptura was launched in São Paulo in 1952, its members, including Waldemar Cordeiro, Geraldo de Barros, Luíz Sacilotto, Judith Lauand and Anatol Władysław were profoundly inspired by Bill’s theories. The Ruptura Movement rejected naturalism in favour of an analytical and theoretical approach to art. Logic and mathematics were tools for understanding and portraying objective reality. Industrially smooth surfaces emphasised that the work of art was independent of the artist. Grupo Frente was formed in Rio de Janeiro in 1954. The artist Ivan Serpa who was actively involved in starting the group, had been a teacher to several of its members at the Museu de Arte Moderna in Rio. Grupo Frente proposed a more exploratory use of concretism. Its proponents included Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape, Aluísio Carvão and Hélio Oiticica. In the late 1950s, a few artists in Grupo Frente sought to merge art and life. A neo-concrete manifesto was written in 1959 by the artist, poet and critic Ferreira Gullar, and signed by other artists, including Franz Weissmann, Lygia Clark and Lygia Pape. They were joined by Hélio Oiticica the following year. These artists opposed the growing rationalist interpretation of concrete art, stating that theory was given too much scope and art was confused with science. Viewers were encouraged to interact with the works by physically shaping and reshaping them. The artists worked in public urban spaces, where the people became part of the creative process. Hélio Oiticica collaborated with a samba school in a favela in Rio. In “Livro da criação” (1959-60), Lygia Pape invites the art audience to shape the narrative by handling the loose parts of the book in a form of creational myth, or a story about creativity.

Info: Curator: Matilda Olof-Ors, Moderna Museet, Exercisplan 4, Skeppsholmen, Stockholm, duration 24/2-13/5/18, Days & Hours: Tue & Fri 10:00-20:00, Wed-thu 10:00-18:00, Sat-Sun 11:00-18:00, www.modernamuseet.se