ART-PRESENTATION: Harald Szeemann-Museum of Obsessions

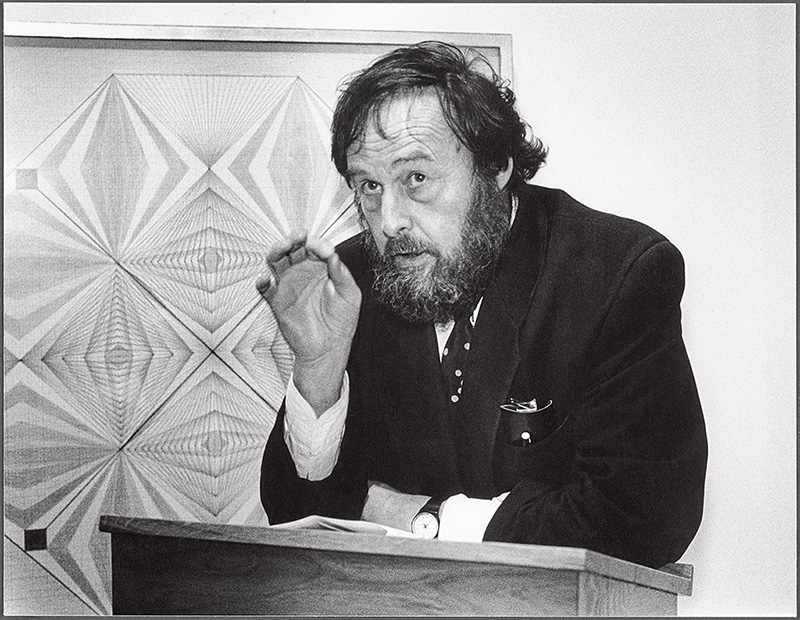

Harald Szeemann (1933-2005) was one of the most influential curators of the recent past, his work was highly complex and cannot be seen as having just a single aspect, as a result an entire generation of curators has been inspired by his independent way of creating exhibitions and his emphatic method of presenting Contemporary Art.

Harald Szeemann (1933-2005) was one of the most influential curators of the recent past, his work was highly complex and cannot be seen as having just a single aspect, as a result an entire generation of curators has been inspired by his independent way of creating exhibitions and his emphatic method of presenting Contemporary Art.

By Dimitris Lempesis

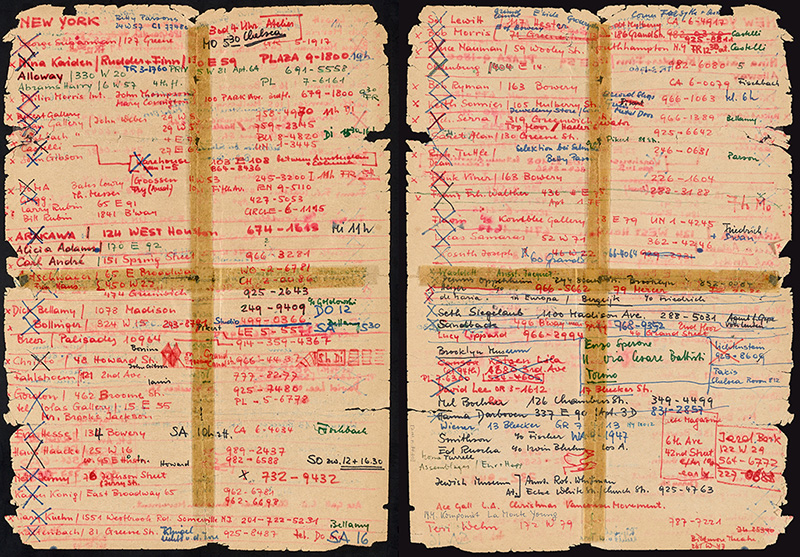

Photo: Getty Research Institute Archive

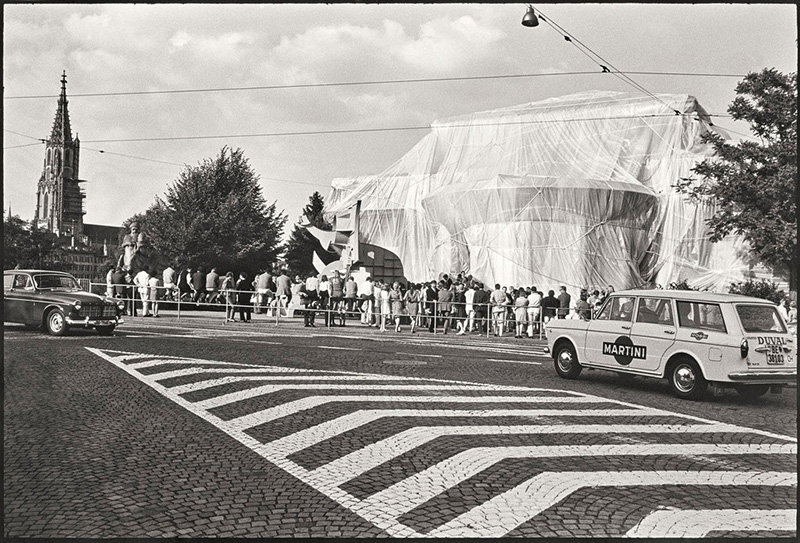

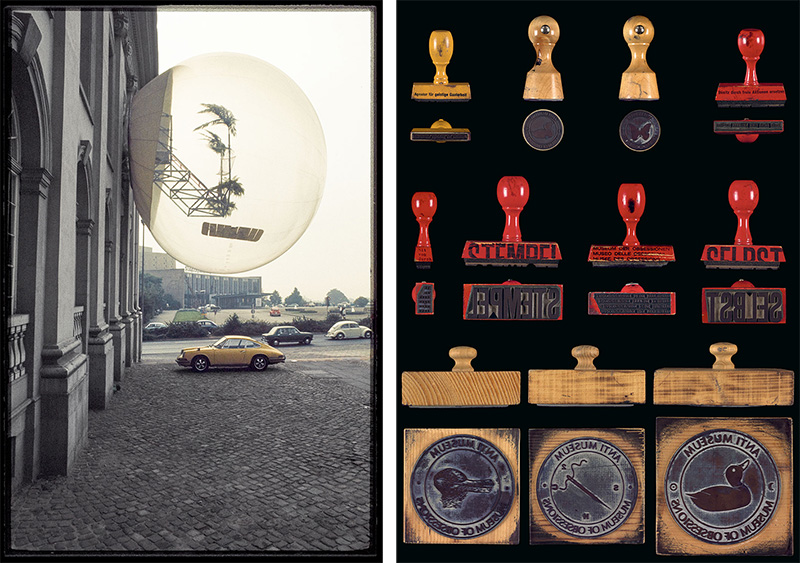

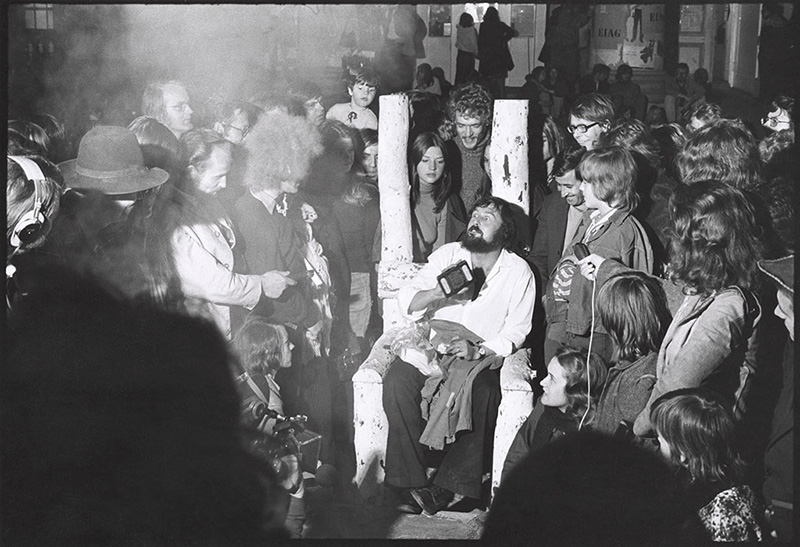

The exhibition “Harald Szeemann-Museum of Obsessions” that is on presentation at the Castello di Rivoli Museum of Contemporary Art is based in his archive and library were acquired by the GRI in 2011. The exhibition is divided into three thematic sections: “Avant-Gardes” which addresses Szeemann’s early exhibitions and his engagements with the Avant Garde of the ‘60s and early ‘70s, “Utopias and Visionaries” which explores a trilogy of exhibitions Szeemann organized in the ‘70s and ‘80s that rewrote the narrative of early 20th-century modernism as a story of alternative political movements, mystical worldviews, and utopian ideologies, and “Geographies” which examines Szeemann’s own Swiss identity, his penchant for travel, and his focus on broad international exhibitions and regional presentations later in his career. Harald Szeemann began his work as a curator in 1957 at Kunstmuseum St. Gallen. In 1961, Szeemann was appointed director of the Kunsthalle Bern in Switzerland, becoming one of the youngest museum directors in the world. During his years there, Szeemann transformed the Kunsthalle into an international showcase, focusing on the most current developments in contemporary art while developing innovative historical and thematic exhibitions. Among these projects were surveys of kinetic art, art of the mentally ill, religious folk art, and science fiction as visual culture, in 1968 gave Christo and Jeanne-Claude their first opportunity to wrap an entire building: the Kunsthalle itself. He organized two major international exhibitions which would cement his reputation as a visionary, “followed by the 5th edition of documenta “Questioning Reality: Pictorial Worlds Today” (1972). With these exhibitions, he moved towards a more experimental approach to curating that, by some accounts, centered the curator as auteur. Szeemann often found himself at odds with artists, trustees, and museum professionals and the intense response to Attitudes led Szeemann to resign from Kunsthalle Bern. Following this period of controversy, Szeemann reinvented himself as an independent curator, organizing exhibitions in non-traditional settings and focused on artists and ideas that may not have enjoyed institutional support. In 1968, Szeemann was approached by the public relations firm Ruder Finn and tobacco conglomerate Philip Morris to produce a major exhibition of recent art. Szeemann embarked on a whirlwind of travel in search of new talent and the resulting exhibition Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form” (1969) was a sprawling display of mostly younger artists on the verge of fame. Many of the artists made their works directly on site, damaging the Kunsthalle Bern in the process: Richard Serra splashed 460 pounds of molten lead against the walls, Joseph Beuys smeared the corners with margarine; Lawrence Weiner removed a section of permanent wall; and Michael Heizer used a wrecking ball to smash up the plaza in front of the Kunsthalle. The exhibition sparked international controversy that ultimately led to Szeemann’s resignation from the Kunsthalle, simultaneously propelling his career to new heights of fame. After resigning from the Kunsthalle, Szeemann became an independent curator, a profession he virtually invented. His first major commission was the exhibition “Happening & Fluxus” (1970) for the Kölnischer Kunstverein in Cologne, Germany. The extensive survey included small galleries devoted to individual artists, and a line of bulletin-board style displays documenting performance art. The more than 600 photographs and ephemera in the exhibition drew less attention, however, than the opening performances, many of which offended the public and titillated the press. Particularly scandalous were the Vienna Actionists. In 1972 Szeemann acted as the secretary general of documenta 5. Szeemann revitalized and radicalized documenta’s program with “Questioning Reality – Image Worlds Today” which is widely regarded as the most significant and ambitious exhibition of the 1970s. Conceived as a “100-day Event,” the expansive exhibition featured dozens of time- and performance-based works by contemporary European and US artists while also devoting smaller sections to socialist realism, political propaganda, art of the mentally ill, advertising, and science fiction. Most prominent among these thematic sections was Individual Mythologies, Szeemann’s category for those artists creating highly subjective alternate realities in the form of large-scale installations. After “Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us”* organized in his apartment in Bern, that showed the personal collection of his grandfather Étienne Szeemann, a famed hairstylist and inventor, Szeemann settled in Ticino in the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland. The trilogy of exhibitions he curated over the next decade was less engaged in contemporary artists and more focused on outsider artists and notions of utopia. “The Bachelor Machines” (1975) explored the erotics of the machine aesthetic in modern art and literature, featuring works by Marcel Duchamp and Robert Müller and commissioning sculptural visualizations based on the writings of Franz Kafka and Alfred Jarry for the exhibition. Szeemann grew deeply interested in the cultural history of the region surrounding his new home, collecting extensive research materials about local visionary artists as well as the political refugees, life-reformers, vegetarians, dancers and other artists who established a commune on the nearby hill known as Monte Verità (the mountain of truth) at the turn of the 20th Century. In 1978 he devoted an entire exhibition to these forgotten figures titled “Monte Verità: The Breasts of Truth”, which was installed in one of the original buildings belonging to the commune. Rounding out this trilogy of exhibitions recasting the modernist tradition was “Tendency toward the Gesamtkunstwerk: European Utopias since 1800” (1983). This show addressed European utopias taking the form of what German opera composer Richard Wagner termed the “total work of art” which sought to combine all of the arts (poetry, music, dance and the visual) to free audience members from the doldrums of the technological age through heightened sensory awareness. In the last fifteen years of his career, Szeemann broadened the focus of his exhibitions to encompass global surveys and explorations of national and regional identity, which dovetailed with his lifelong interest in travel and geography. He organized biennials in Lyon (1997), Gwangju (1997), Seville (2004) and Venice on two separate occasions (1999 and 2001). In exhibitions like “Visionary Switzerland” (1991), “Austria in a Net of Roses” (1996), “Beware of Exiting Your Dreams: You May Find Yourself in Somebody Else’s” (2000), “Blood & Honey: The Future Lies in the Balkans” (2003) and “Visionary Belgium” (2005), Szeemann took a singular approach to the representation of single nations and cultural regions, bringing together a remarkable range and number of cultural artifacts that often featured graphic wallpapers, salon-hung walls, and impressive large-scale installations.

Info: Curators: Glenn Phillips, Philipp Kaiser, Doris Chon and Pietro Rigolo,Castello di Rivoli Museum of Contemporary Art, Piazza Mafalda di Savoia, Rivoli, Turin, Duration: 26/2-26/5/19, Days & Hours: Tue-Fri 10:00-17:00, Sat-Sun 10:00-19:00, www.castellodirivoli.org