ART-TRIBUTE:Women House,Part I

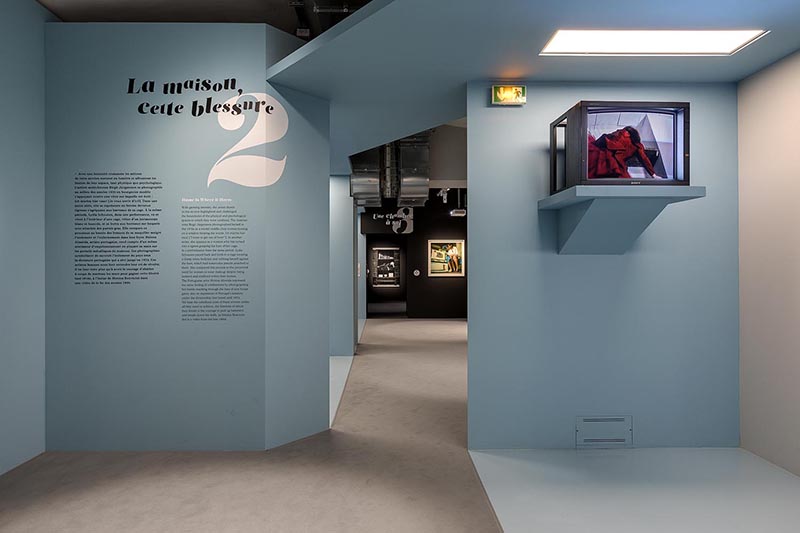

Questions about a woman’s “place” resonate in our culture, and conventional ideas persist about the house as a feminine space, 39 contemporary artists in the exhibition “Women House” recast conventional ideas about women and the home with acuity and wit, creating provocative photographs, videos, sculptures and room-like installations built with materials ranging from felt to rubber bands (Part II).

Questions about a woman’s “place” resonate in our culture, and conventional ideas persist about the house as a feminine space, 39 contemporary artists in the exhibition “Women House” recast conventional ideas about women and the home with acuity and wit, creating provocative photographs, videos, sculptures and room-like installations built with materials ranging from felt to rubber bands (Part II).

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Monnaie de Paris Archive

The exhibition “Women House” places women in the focus of an Art and Architecture History from which they were absent. Their work question foregone conclusions with precision, pinpointing their theoretical–and sometimes political nature: the 8 chapters of the exhibition display a complexity of possible viewpoints on the matter. The exhibition’s title pays homage to a seminal turning point in the history of Feminist Art, the exhibition “Womanhouse” (30/1-28/2/1972), organized by Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, co-founders of the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). The 25 artists worked on a collective piece: transforming an old mansion into an installation and performance space. The eight sections of the exhibition reflect the complexity of possible perspectives on the topic: they are not only feminist (Desperate Housewives), but also poetic (A Room of One’s Own), political (Mobile-Homes) and nostalgic (Dolls’ Houses). Birgit Jürgensse photographed herself in the 1970s as a model middleclass woman leaning on a window bearing the words: “I want to get out of here!”. In a performance from the same period, Lydia Schouten paced back and forth in a cage wearing a damp white bodysuit and rubbing herself against the bars, which had watercolor pencils attached to them. She compared this process to the perceived need for women to wear makeup despite being isolated and confined within their homes. Helena Almeida expressed the same feeling of confinement by photographing her hands reaching through the bars of iron house gates, also an expression of Portugal’s isolation under the dictatorship that lasted until 1974. In a recent series, Zanele Muholi captures moments of intimacy shared by lesbian couples, whose mimetic postures express a sense of complementarity. These women are photographed inside their homes: here, the home seems to act as a refuge, a place of resistance against “the hate crimes taking place in South Africa or elsewhere against homosexuals”. Rachel Whiteread designed a “Modern Chess Set” based on reproductions of objects from a doll’s house belonging to her. Instead of a king and queen, an ironing board and a stove are placed on a chessboard made of mismatched pieces of carpet: the artist replaces the codes of a game with day-to-day objects used by a housewife. The work by Nazgol Ansarinia recreates a wall of a demolished building in Teheran, while Isa Melsheimer’s model evokes the roof garden of the apartment designed by Le Corbusier for the art collector Charles de Beistegui in the 1920s: a space with walls 1.5 meters high providing glimpses of Paris monuments. A piece of embroidery completes the installation and shows these views. Ana Vieira’s “Environment/Dining Room” seems both familiar and strange. It is constructed from gauze panels reproducing the clichés of a bourgeois interior in which the strict orderliness of the objects is matched only by their oppressive ordinariness. “Triplice Tenda” by Carla Accardi, one of the few women on the post-war Italian art scene, consists of three many-sided tents nested inside one another. Their arabesque motifs are evocative of Byzantine monuments, while their pink color references the intimacy of the body. For Accardi, the tent symbolizes “a life of freedom outside of the structured framework of civilization”. The formal association between the female body and the architecture of the house was first made in a series of paintings by Louise Bourgeois in 1945-1947. Her “Femmes-maisons” show the extent to which women were still being absorbed or devoured by the home, which it was their role to nourish and support. Fifty years later, Bourgeois explored the same theme in a different way in her “Spiders” series. The spider represents the protective mother, and her eggfilled belly is a lair: an architectural structure that also affords protection. From the 1960s on, Niki de Saint Phalle created her series of “Nanas-maisons”: as they grew, her nanas took on an architectural dimension, their generously proportioned bodies opening up so that visitors may enter, take refuge and allow their imaginations to run free. Elsa Sahal shares the same heritage of Louise Bourgeois and Niki de Saint Phalle, designing self-portraits in the form of caves that become symbols of the maternal womb: the life-giving, sheltering belly. We also find fragmented body imagery in Anne-Marie Schneider’s drawings, her “Body-houses” which stand somewhere between caricature and satirical rage, have a kind of humor that is as dark as her pencil strokes.

Info: Curators: Camille Morineau and Lucia Pesapane, Monnaie de Paris, 11 quai de Conti, Paris, Duration: 20/10/17-28/1/18, Days & Hours: Tue-Wed & Fri-Sun 11:00-19:00, Thu 11:00-21:00, www.monnaiedeparis.fr