ARCHITECTURE:Japan-ness, Part I

To exhibit Japanese architecture is to offer a broader perspective that clearly shows the diversity of this scene and the defining place in Japanese culture of architects’ works, often ignored by the Western world. The challenge is also to contextualize the movements and schools which, inspired by reflection, controversy and debate, have formed the pluralism of Japanese architecture (Part II).

To exhibit Japanese architecture is to offer a broader perspective that clearly shows the diversity of this scene and the defining place in Japanese culture of architects’ works, often ignored by the Western world. The challenge is also to contextualize the movements and schools which, inspired by reflection, controversy and debate, have formed the pluralism of Japanese architecture (Part II).

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Centre Pompidou-Metz

The exhibition “Japan-nness”, made up of important pieces from the Collection of Centre Pompidou-National Museum of Modern Art, has been enriched with numerous loans from the private archives of architects and Museum or University collections. With 70 original models, more than 200 drawings, films and documents presenting more than 300 iconic projects, the exhibition traces the history of urban and economic changes in Japan since 1945, a history marked by profound social and cultural developments. The exhibition is punctuated by photographs and experimental film presentations, allowing to better understand the lifestyles defined by contemporary urban models. Following a chronological path from 1945 to the present day, the exhibition is divided into six periods, colour coded, starting from black and ending with white. Each period consists of a display of urban environments and architectural projects, to offer a better understanding of the creative challenges in the social, political and economic contexts of the period.

DESTRUCTION AND REBIRTH (1945): It took the terrible rupture of the Second World War and nuclear destruction for Japan to question the specificity of its architecture and its relation to the city. If the architecture of traditional shrines (like those in Ise), which are constantly destroyed and rebuilt, offers a certain idea of permanence and history, the concept of the “traditional house” and the consciousness of a distinct architectural identity did not emerge until the 1930s through the writings of the German architect Bruno Taut. The concept of architecture in Japan was thus developed in close connection with the emergence of Western modernism. After a strong movement dominated by eclecticism, the very idea of architecture and a form of expression emerged with the Bunriha kenchikukai movement (1920), inspired by the writings of Sutemi Horiguchi and then by Ryuichi Hamaguchi. The Second World War represented the extreme affirmation of technology and of an industrialisation driven by the militarisation of society, a forced modernism which was completed in the tragedies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Construction and destruction form a cycle that has shaped Japanese culture since the fires of the Edo period (1603-1868) and the Kanto earthquake (1923). This first room of the exhibition, marked by the colour black, illustrates this cycle of time, from destruction to rebirth, but also a tradition of concealing, of shadow and of darkness.

CITIES AND LAND, A WORK IN PROGRESS (1945-1955): War gives rise to the idea of extreme destruction, a possible eradication of man by nuclear weapons, and in return brings an awareness of a new form of humanism. Examining man’s place in a rapidly developing industrial society is illustrated by Seiichi Shirai’s “Temple of Atomic Catastrophes” (1955) project and Kenzo Tange’s “Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park” (1952-1955). A number of Japanese architects who had taken their model for architectural innovation from the 1930s and Le Corbusier, were inspired after the war by his humanist vision of the city. In the same way, Kunio Mayekawa, Junzo Sakakura and Takamasa Yosizaka imposed themselves as masters of a brutalist architecture, with a systematic use of concrete, a flexible form of expression, and lending a human dimension to collective projects (town halls, cultural centres, universities). Far from simply using the Corbusian form of expression, these architects, followed by a new generation, found through Charlotte Perriand and Jean Prouvé the principle of construction for a more economic and social architecture that played a part in the reconstruction of the country with projects by Junzo Sakakura and Makoto Masuzawa amongst others.

EMERGENCE OF MODERN JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE (1955-1965): Japan’s burgeoning economic and industrial growth was accompanied by many architectural achievements. The expansion of Japanese cities was orchestrated by large construction companies (such as Kajima, Obayashi, Shimizu, Taisei and Takanaka). The work of architects became essential, either through companies like Nikken Sekkei who recruited large teams, or thanks to the growing importance of some agencies. Through the affirmation of an international style, prominant figures established themselves, such as Antonin Raymond, Kunio Mayekawa, Junzo Sakakura… Kenzo Tange became the most iconic architect of this period with his design in 1964 of the Yayogi National Stadium built for the Olympic Games in Tokyo, a true icon of the new Japanese architecture. Well-known architectural firms such as Kiyonori Kikutake, Masato Otaka and the young Arata Isozaki became showcases for architectural creativity in Japan. Their development reflected their hopes for a new modernity. Indeed, in reaction to a modernism considered too formal, other architects, including the iconic figure of Seiichi Shirai, opted for a more narrative architecture, on a human scale and enriched by the use of a variety of materials. International recognition emerged through publications on Japanese architecture. Numerous projects were published for their exemplary nature, such as Kiyonori Kikutake’s Sky House (1958), Kenzo Tange’s St Mary’s cathedral (1964) and Arata Isozaki’s Oita Medical Hall (1960).

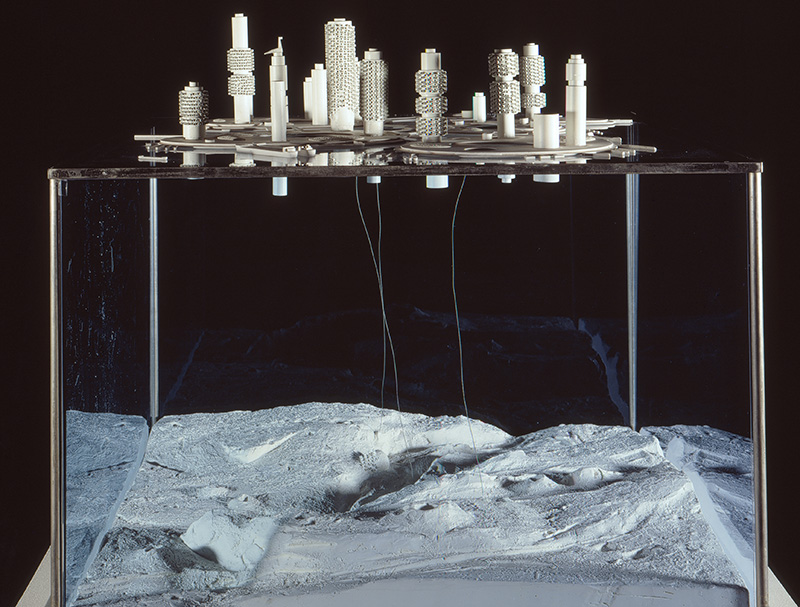

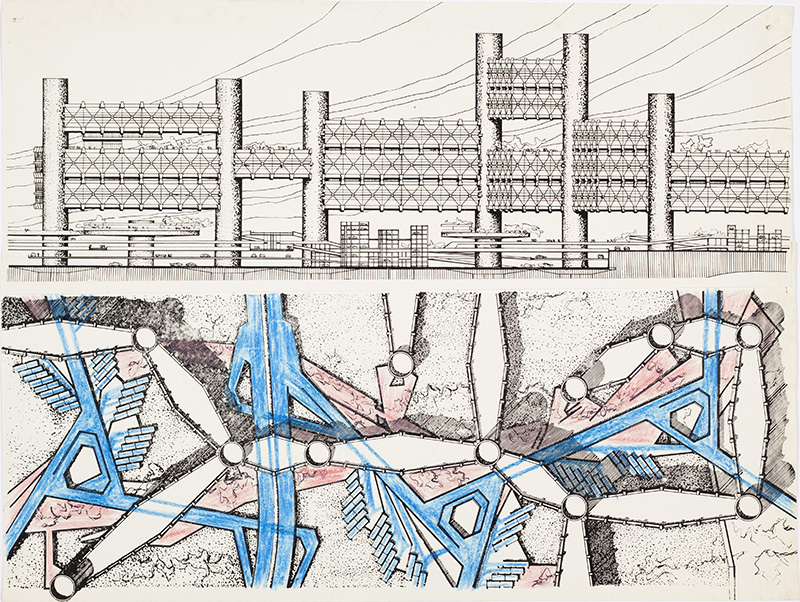

METABOLISM, OSAKA 1970 AND THE “NEW VISION” (1965-1975): The 1960s, accompanied by intense industrial development, saw the emergence of research into new materials and technological innovations. Now famous architects such as Kisho Kurokawa, Kiyonori Kikutake, Masato Otaka, Fumihiko Maki and Arata Isozaki asserted the modular and flexible character of their architecture, made up of an agglomeration of cellular units. They proposed open architecture and developed new strategies for urban expansion. The reputation of the Metabolism movement was established at Osaka 1970. Its experimental pavilions became a global manifesto for a new technological architecture. Osaka 1970 recognised the megastructures of Kenzo Tange, Kisho Kurokawa and Kiyonori Kikutake, as well as the inflatables of Yutaka Murata. These creations influenced young architects all over the world. The visionary architecture offered new ways of looking at large-scale urban design, as prefigured by the mega-structures of Arata Isozaki, the marine cities of Kenzo Tange, Kiyonori Kikutake, and even the Okinawa International Ocean exposition in 1975, where Kikutake presented a floating city. Osaka 1970 also attracted criticism from architects. Arata Isozaki distanced himself from metabolism and criticised the severe forms of modernism. Alongside a mediatised architecture, pop architecture emerged. Kijo Rokkaku projected the appearance of colour across the city. The buildings Ichi Ban Kan (1969) and Ni Ban Kan (1970) by Minoru Takeyama and Ryoichi Shigeta’s Chimneys (1969) testify to a joyful architecture that can also be seen in the drawings of Kiko Mozuna (Kushiro City Museum, 1984). Architects then found great freedom of expression using architecture as images in the city, such as Kazumasa Yamashita with his Face House (1974) or Tatsuhiko Kuramoto with his Bachan-chi or grandmother’s house (1972).

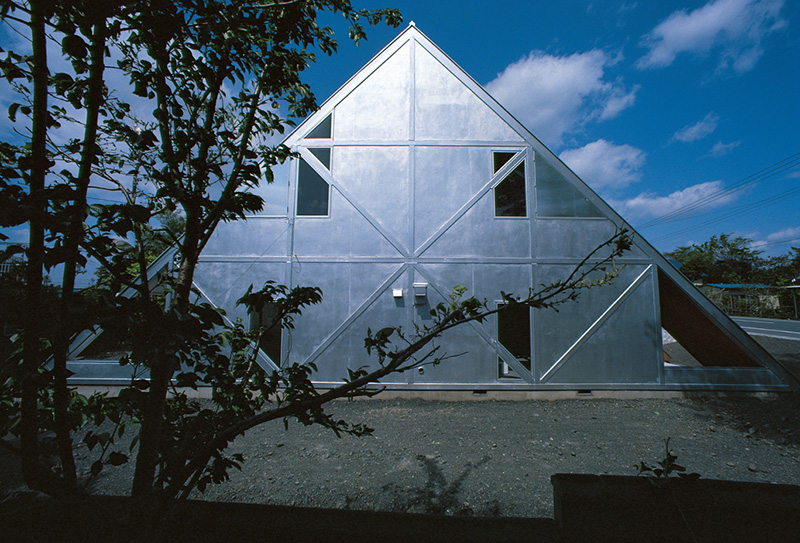

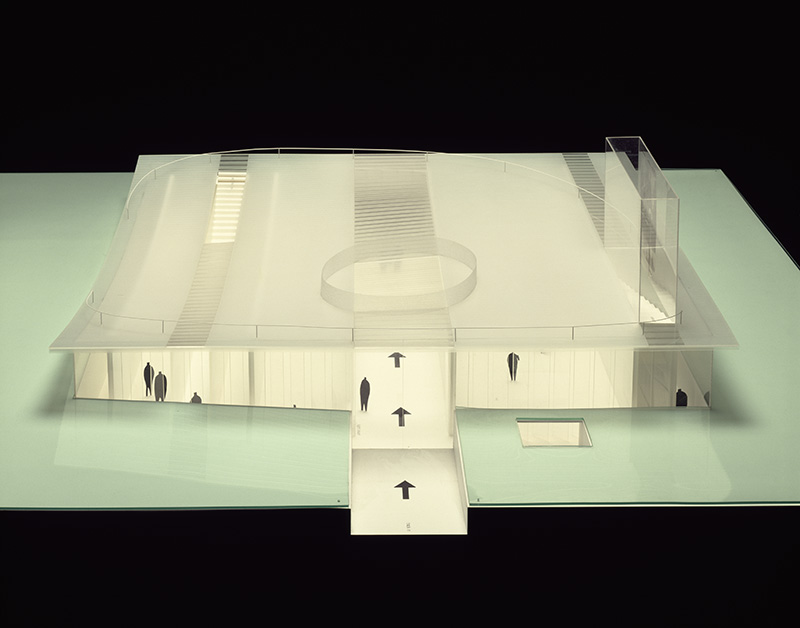

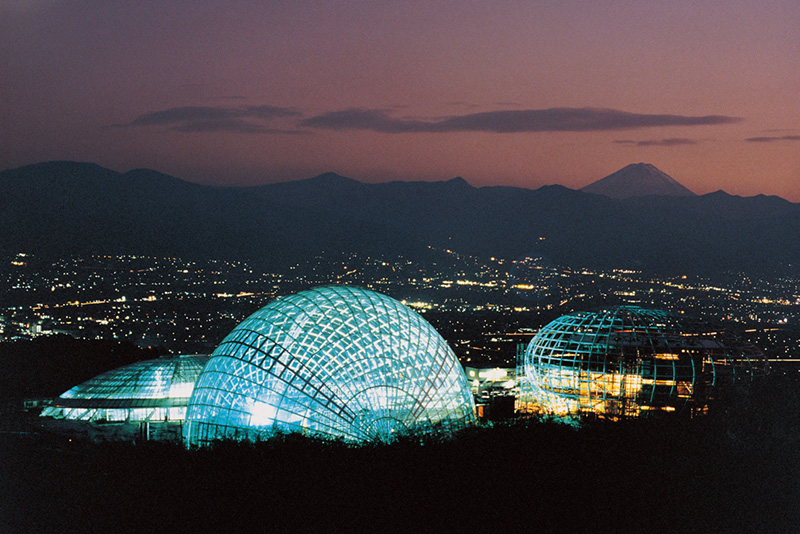

THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ARCHITECTURE (1975-1995): The 1980s-1990s are associated with intellectualism and a consolidation of ties with occidental countries. After the political movements of 1968, a new generation of architects broke away from a technological architecture too closely linked to the industrial environment and the idealistic optimism of the 1970s. A return to simple typologies, towards a reinterpretation of the living space constitutes the basis of Kazuo Shinohara’s explorations. He introduced a new vocabulary for the single house built using simplified forms and construction methods. Japanese architecture established itself at that time as a reflection on space, materials and light. The return to simple geometric shapes enshrined a minimalist architecture influenced by structuralism, immediately recognized across the world. Tadao Ando, with his dwellings of raw concrete interacting with the light, asserted this structure as a language. Other architects developed a more philosophical view of architectural forms, such as Takefumi Aida or Hiromi Fujii, the main exponents of structuralist architecture. Conversely, others were inspired by a more technological mode of expression, in which architecture is transformed into an autonomous machine, such as Shin Takamatsu and Hiroshi Hara who continued his visionary exploration of High Tech architecture. Itsuko Hasegawa was best able to synthesise investigations into the living space and new materials. She invented the concept of “light architecture”, made of metallic meshes that make the structure disappear. This erasing of architecture was brought to fruition in the work of Toyo Ito, whose “PAO II” (1989) structure has been reconstructed for the exhibition.

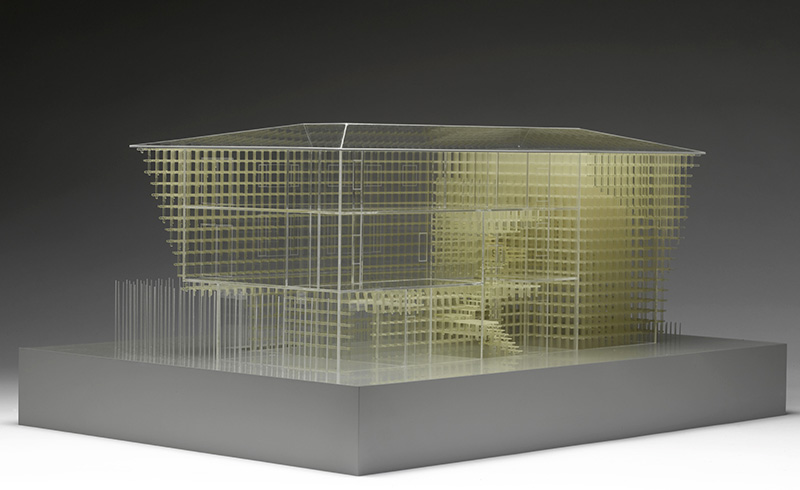

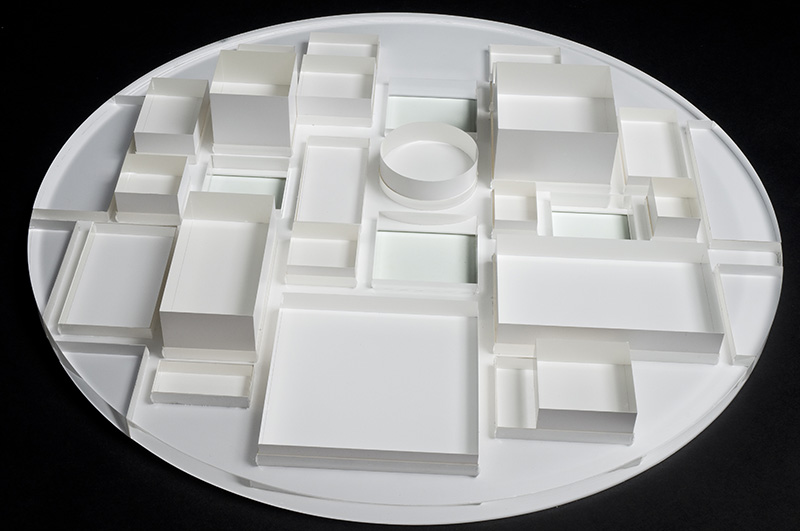

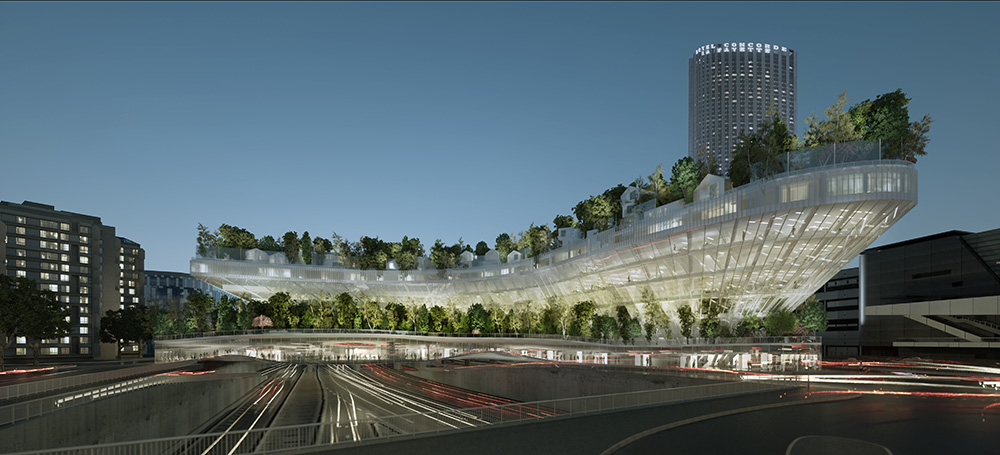

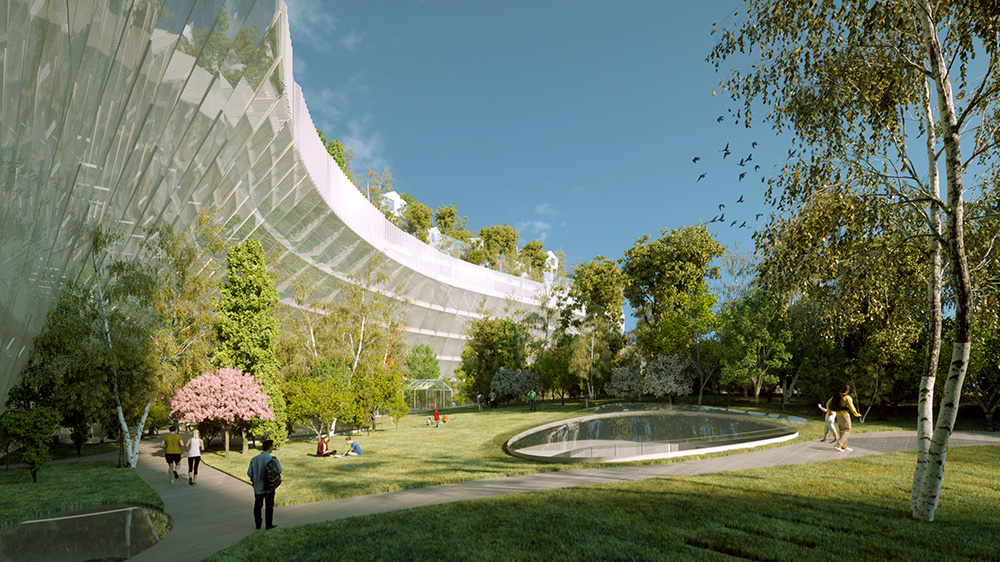

OVEREXPOSED ARCHITECTURE, IMAGES AND NARRATIVES (1995 TO THE PRESENT DAY): The last section of the exhibition highlights the generation of Japanese architects who emerged in the early 2000s, widely recognized internationally through SANAA (Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa), Kengo Kuma and Shigeru Ban Studios, followed nowadays by Junya Ishigami and Sou Fujimoto. From the 1990s, Japanese architecture was no longer only recognized through a few big names, but became one of the most important stages for architectural creation in the world. It was, of course, very evident in Japan thanks to numerous projects, but also abroad, with many Japanese architects pursuing an international career. Even if the aesthetics of a “disappearing architecture” using glass and transparent materials remained dominant, other forms of exploration with materials emerged in the work of Kengo Kuma and Shigeru Ban. With architects from the emerging generation such as Tezuka Architects, contemporary Japanese architecture reinvented the city by redefining new programmes: small dwellings built in the gaps between existing constructions, social projects, designed as new meeting places, reactivating the organic role of town planning. More recent projects seem to reconnect with the idea of narrative architecture, referring to a certain archaic style, such as with Terunobu Fujimori, or by investing a more symbolist vision of architecture, such as with Jun Aoki, Kumiko Inui and Junya Ishigami, who invented new narratives and stories describing a different relationship with nature and with the world of trade and industry.

Info: Curators: Frédéric Migayrou and Yuki Yoshikawa, Centre Pompidou-Metz, 1 Parvis des Droits-de-l’Homme, Metz, Duration: 9/9/17-8/1/18, Days & Hours: From 1/4-31/10: Mon & Wed-Thu 10:00-18:00, Fri-Sun 10:00-19:00, From, 1/10-31/3: Mon & Wed-Sun 10:00-18:00, www.centrepompidou-metz.fr