TRACES: Louise Bourgeois

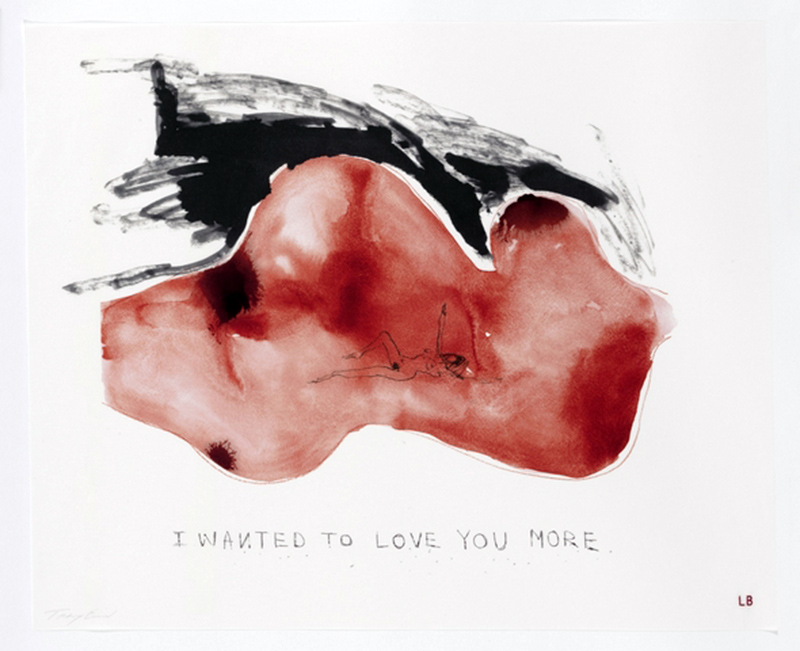

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Louise Bourgeois (25/12/1911-31/5/2010). Bourgeois transformed her experiences into a highly personal visual language through the use of mythological and archetypal imagery, adopting objects such as spirals, spiders, cages, medical tools, and sewn appendages to symbolize the feminine psyche, beauty, and psychological pain. Her work helped inform the burgeoning Feminist Art Movement and continues to influence feminist-inspired work and installation art. This column is a tribute to very important artists, living or dead, who have left their trace in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Louise Bourgeois (25/12/1911-31/5/2010). Bourgeois transformed her experiences into a highly personal visual language through the use of mythological and archetypal imagery, adopting objects such as spirals, spiders, cages, medical tools, and sewn appendages to symbolize the feminine psyche, beauty, and psychological pain. Her work helped inform the burgeoning Feminist Art Movement and continues to influence feminist-inspired work and installation art. This column is a tribute to very important artists, living or dead, who have left their trace in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Efi Michalarou

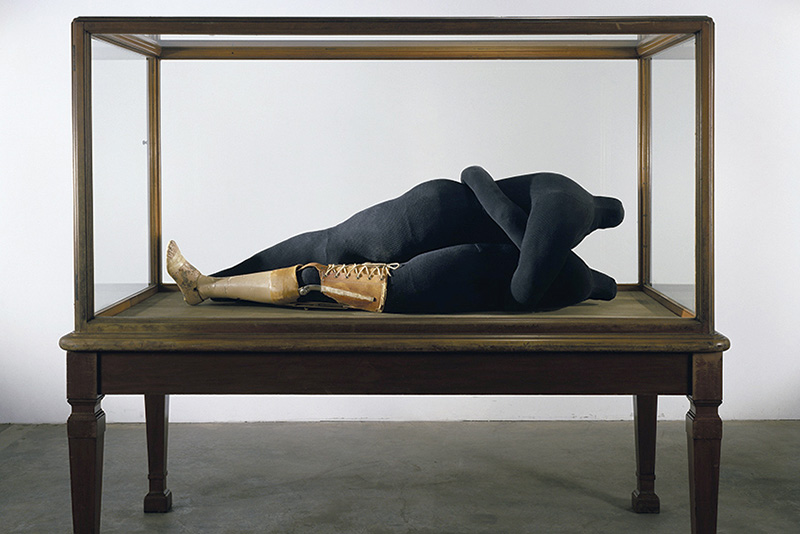

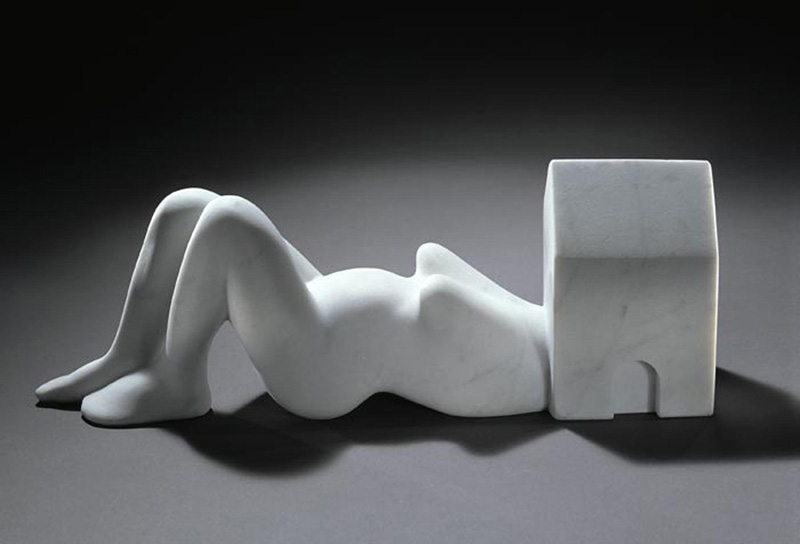

Louise Bourgeois was born in Paris to Louis Bourgeois and Joséphine Fauriaux. The family lived on Boulevard Saint Germain, where Louis and Joséphine continued the Fauriaux family antique business by opening a tapestry gallery. In 1919, the family acquired a property in Antony, a suburb of Paris, which included an atelier for the restoration of tapestries. It was also around this time that Bourgeois’s mother, Joséphine, contracted the Spanish flu, from which she never fully recovered. Winters were spent in warmer climates, and Bourgeois’s education was frequently interrupted to help care for her mother. In 1922, the British au pair Sadie Gordon Richmond entered the Bourgeois family to teach the children English. Living with them for almost a decade, Sadie also became Louis’s mistress. This entangled situation, and the effect her father’s behavior had on Bourgeois, would later find expression in her art. Bourgeois’s childhood memories, her involvement in the family tapestry business, and the caregiving she provided her mother, along with pervasive feelings of abandonment, would become important themes in her work. Bourgeois’s mother died in September 1932. In November of that year, after receiving her baccalaureate in philosophy from the Lycée Fénelon in Paris, Bourgeois entered the Sorbonne to study mathematics. However, profoundly depressed by her mother’s death, she soon turned to art. Bourgeois attended several different academies and artist’s ateliers in Paris, and took classes at the Académie de la Grande-Chaumière, the École des Beaux-Arts, and the École du Louvre. During this time, she also studied with Fernand Léger, who told her that her sensibility leaned toward the three-dimensional. In 1938, Louise Bourgeois met and married the American art historian Robert Goldwater and moved to New York City, where they raised three sons. Soon after her arrival in New York, Bourgeois enrolled at the Art Students League, where she began to make prints, and in 1945, she had her first solo exhibition of paintings at the Bertha Schaefer Gallery, New York. She began creating sculptural forms out of found wood on the roof of her apartment building the mid-‘40s. In 1949, Bourgeois exhibited this work for the first time in a solo exhibition, “Recent Work 1947–1949: Seventeen Standing Figures in Wood”, at the Peridot Gallery, New York. Two more solo exhibitions at the Peridot Gallery would follow in 1950 and 1953. In 1951, the Museum of Modern Art acquired “Sleeping Figure” (1950). Throughout the ‘40s and ‘50s, Bourgeois’s work was presented with Abstract Expressionist artists, including Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Willem de Kooning, in various group exhibitions. She was in contact with European artists in New York such as Marcel Duchamp, André Breton, and Joan Miró. In 1946, Bourgeois began making prints at Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17. In 1947, she produced a seminal print project, “He Disappeared Into Complete Silence”, in which nine engravings, accompanied by her parables, were distinctly architectural in theme. After the unexpected death of her father in 1951, Bourgeois fell into a deep depression, which led to her psychoanalysis with Dr. Henry Lowenfeld. She was particularly combative, and hated the standard of powerless woman. For that reason, when the Abstract Expressionists, who joined them in 1954, talked to exclude from the Movement: Women, Blacks and Gays (Abstract Expressionism and Other Politics, Yale University Press Editions), Louis Bourgeois, erected her fist and hit with momentum and anger the table, claiming the right of all the above to be acceptable in the movement and it looks that she succeeded. These separations inappropriate nowadays, were previously almost self-explanatory(!). However, such thoughts, beliefs and prejudices would cost much in Contemporary Art. In 1964, after a period of relative seclusion, she had her first solo show in eleven years at the Stable Galler in New York. Her new work, made in plaster and latex, revealed a turn toward more organic processes, and introduced the “Lair” as a unique sculptural form. In 1966, Lucy Lippard included Bourgeois’s work in the seminal exhibition “Eccentric Abstraction”, together with a younger generation of artists like Eva Hesse and Bruce Nauman. In the late ‘60s and early ’70s, Bourgeois frequently traveled to Italy to work in marble and bronze. Bourgeois’s husband died in March 1973. In 1974, she created “The Destruction of the Father”, which was shown for the first time in a solo show at 112 Greene Street in New York the same year. In 1978, she staged a performance “A Banquet: A Fashion Show of Body Parts” within her first spatial environment, “Confrontation” (1978), at the Hamilton Gallery of Contemporary Art, New York. In 1980, she met Jerry Gorovoy, who included her in a group show he curated at the Max Hutchinson Gallery, New York. Gorovoy would subsequently become her full-time assistant and remained a constant presence for the rest of her life.

Louise Bourgeois was born in Paris to Louis Bourgeois and Joséphine Fauriaux. The family lived on Boulevard Saint Germain, where Louis and Joséphine continued the Fauriaux family antique business by opening a tapestry gallery. In 1919, the family acquired a property in Antony, a suburb of Paris, which included an atelier for the restoration of tapestries. It was also around this time that Bourgeois’s mother, Joséphine, contracted the Spanish flu, from which she never fully recovered. Winters were spent in warmer climates, and Bourgeois’s education was frequently interrupted to help care for her mother. In 1922, the British au pair Sadie Gordon Richmond entered the Bourgeois family to teach the children English. Living with them for almost a decade, Sadie also became Louis’s mistress. This entangled situation, and the effect her father’s behavior had on Bourgeois, would later find expression in her art. Bourgeois’s childhood memories, her involvement in the family tapestry business, and the caregiving she provided her mother, along with pervasive feelings of abandonment, would become important themes in her work. Bourgeois’s mother died in September 1932. In November of that year, after receiving her baccalaureate in philosophy from the Lycée Fénelon in Paris, Bourgeois entered the Sorbonne to study mathematics. However, profoundly depressed by her mother’s death, she soon turned to art. Bourgeois attended several different academies and artist’s ateliers in Paris, and took classes at the Académie de la Grande-Chaumière, the École des Beaux-Arts, and the École du Louvre. During this time, she also studied with Fernand Léger, who told her that her sensibility leaned toward the three-dimensional. In 1938, Louise Bourgeois met and married the American art historian Robert Goldwater and moved to New York City, where they raised three sons. Soon after her arrival in New York, Bourgeois enrolled at the Art Students League, where she began to make prints, and in 1945, she had her first solo exhibition of paintings at the Bertha Schaefer Gallery, New York. She began creating sculptural forms out of found wood on the roof of her apartment building the mid-‘40s. In 1949, Bourgeois exhibited this work for the first time in a solo exhibition, “Recent Work 1947–1949: Seventeen Standing Figures in Wood”, at the Peridot Gallery, New York. Two more solo exhibitions at the Peridot Gallery would follow in 1950 and 1953. In 1951, the Museum of Modern Art acquired “Sleeping Figure” (1950). Throughout the ‘40s and ‘50s, Bourgeois’s work was presented with Abstract Expressionist artists, including Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Willem de Kooning, in various group exhibitions. She was in contact with European artists in New York such as Marcel Duchamp, André Breton, and Joan Miró. In 1946, Bourgeois began making prints at Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17. In 1947, she produced a seminal print project, “He Disappeared Into Complete Silence”, in which nine engravings, accompanied by her parables, were distinctly architectural in theme. After the unexpected death of her father in 1951, Bourgeois fell into a deep depression, which led to her psychoanalysis with Dr. Henry Lowenfeld. She was particularly combative, and hated the standard of powerless woman. For that reason, when the Abstract Expressionists, who joined them in 1954, talked to exclude from the Movement: Women, Blacks and Gays (Abstract Expressionism and Other Politics, Yale University Press Editions), Louis Bourgeois, erected her fist and hit with momentum and anger the table, claiming the right of all the above to be acceptable in the movement and it looks that she succeeded. These separations inappropriate nowadays, were previously almost self-explanatory(!). However, such thoughts, beliefs and prejudices would cost much in Contemporary Art. In 1964, after a period of relative seclusion, she had her first solo show in eleven years at the Stable Galler in New York. Her new work, made in plaster and latex, revealed a turn toward more organic processes, and introduced the “Lair” as a unique sculptural form. In 1966, Lucy Lippard included Bourgeois’s work in the seminal exhibition “Eccentric Abstraction”, together with a younger generation of artists like Eva Hesse and Bruce Nauman. In the late ‘60s and early ’70s, Bourgeois frequently traveled to Italy to work in marble and bronze. Bourgeois’s husband died in March 1973. In 1974, she created “The Destruction of the Father”, which was shown for the first time in a solo show at 112 Greene Street in New York the same year. In 1978, she staged a performance “A Banquet: A Fashion Show of Body Parts” within her first spatial environment, “Confrontation” (1978), at the Hamilton Gallery of Contemporary Art, New York. In 1980, she met Jerry Gorovoy, who included her in a group show he curated at the Max Hutchinson Gallery, New York. Gorovoy would subsequently become her full-time assistant and remained a constant presence for the rest of her life.