INTERVIEW: Andres Serrano

Andres Serrano is one of the most famous Contemporary American visual photographers. I always admire his work, not because the fact that when he first started his series with the complete deposition of the religious symbols he shocked many people, but because through his provocation, I made distinction of a caustic humor and a very well hidden sensitivity for the suffering behind the entrenched social, political and religious tactics and ideas. My faith in an artist whom I discovered and presented on the Greek Mass Media with great frequency in the late ’90s, who for that time was groundbreaking, was confirmed by ”Tortune”, his excellent and diametrically opposite series of works. On the occasion of his solo exhibition at Galerie Natalie Obadia in Paris, we discuss for a primitive subject such as pain and torture and how he experienced and chronicled them through his work. At the same time at Mep (La Maison de la photographie) in Paris, is on presentation a series of works from his series “America”, “Residents of New York”, “Denizens of Brussels” and an installation of his “Signs of the Times” project.

Andres Serrano is one of the most famous Contemporary American visual photographers. I always admire his work, not because the fact that when he first started his series with the complete deposition of the religious symbols he shocked many people, but because through his provocation, I made distinction of a caustic humor and a very well hidden sensitivity for the suffering behind the entrenched social, political and religious tactics and ideas. My faith in an artist whom I discovered and presented on the Greek Mass Media with great frequency in the late ’90s, who for that time was groundbreaking, was confirmed by ”Tortune”, his excellent and diametrically opposite series of works. On the occasion of his solo exhibition at Galerie Natalie Obadia in Paris, we discuss for a primitive subject such as pain and torture and how he experienced and chronicled them through his work. At the same time at Mep (La Maison de la photographie) in Paris, is on presentation a series of works from his series “America”, “Residents of New York”, “Denizens of Brussels” and an installation of his “Signs of the Times” project.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Galerie Natalie Obadia Archive

Mr. Serrano, as we know you are exhibiting at two different spaces in Paris (Galerie Natalie Obadia and Maison Européenne de la Photographie), a series of artworks that while they look different, they are focused on the human being. Would you like to explain to us about this selection?

I often use portraiture as a means of expression to cover a wide range of subjects: America, The Klan, The Morgue, The Church, The Residents of New York and The Denizens of Brussels are portraits of individuals and symbols at the same time. They are archetypes of our times. It’s hard for me to take a picture that means nothing. I like to make art about something, even if it’s not clear what I mean by it. It’s not important how I see it but how you see it. At the M.E.P. exhibition, there is a portrait of Donald Trump. I took Donald Trump’s portrait in 2004 for my “America” series. I started “America” in 2001 as a response to Sept.11th. America had been attacked as the enemy and I wanted to show who the “enemy” is. I did more than a hundred portraits of people from all walks of life. I started with the symbols of Sept.11, the firemen, the airline pilot, the F.B.I. agent in a Hazmat suit, the soldier, the Postal Worker… then went on to photograph the poor, the working class, the middle class, the fortunate and unfortunate, and finally, the rich and celebrated. Now, twelve years later, Donald Trump’s picture means something although what it means, is up to you. Everything is in the eyes of the beholder and perception is subjective. The Torture series at Nathalie Obadia Gallery is my most recent work. It’s part of a large body of work on torture. It not only reveals the tortured but the torturer himself. In doing this work I had to become the Torturer. It’s easy to torture people when you have power over them. In the end, even though the many bodies of work look different, it’s always the same picture: It’s a portrait of the artist.

The series “Torture”, that are is on exhibition at Galerie Natalie Obadia, as we know, starts from the proposition that you accepted in 2005 by the New York Times Magazine, to make a series of photographs on the occasion of the article: “What We Do not Talk About When We Talk About Torture”, which was negotiating the Silence After Abu Ghraib. What was it that prompted you to return at 2015-16 on the same subject?

In 2015 I met Andrei Tretyakov, the Founder of a/political, an organization based in London that supports socially engaged projects by artists. Andrei asked me If there was something a/political could help me with and I said, “Yes, Torture.” I thought the project might appeal to Andrei and I was right. It was thanks to a/political that I was able to do this project. It involved travelling to a great number of cities and countries photographing torture museums, concentration camps and detention centers, The Hooded Men of Northern Ireland and finally The Foundry in Mauborguet, an artist in residence run by the artist Andrei Molodkin. It was at The Foundry where I did Abu Ghraib type renactments of torture victims.

The people you met, the torture sites you had visited and the emotions you felt, created an open topic for discussion and exploration?

The only discussions I had were with my wife, Irina, Andrei Molodkin and Becky Haghpanah-Shirwan, the director of a/political. Irina and Andrei are artists so they understand and Becky organized everything. When working on a new body of work I generally don’t talk about it, I just do it. I only talk to the people who need to know and only when they need to know it.

We observe that while the victims of torture are shown in full realism, the medieval instruments are approached almost like jewelry or still life. Why?

They’re still lifes of horrible objects. But the perversity is that there is great beauty in these objects. With the passage of time and divorced from their original intent, we can look at these objects with an aesthetic eye. The craftsmanship of these instruments gives them the patina of medieval metalworks much like the arms and armor of The Louvre or The Met. This is the duality of my work, the push and pull; the Beauty and the Beast. You can’t have one without the other.

How difficult was it emotionally for you, but also for the victims, like Fatima or the four members of the Irish Republican Army to relive their suffering in the shooting?

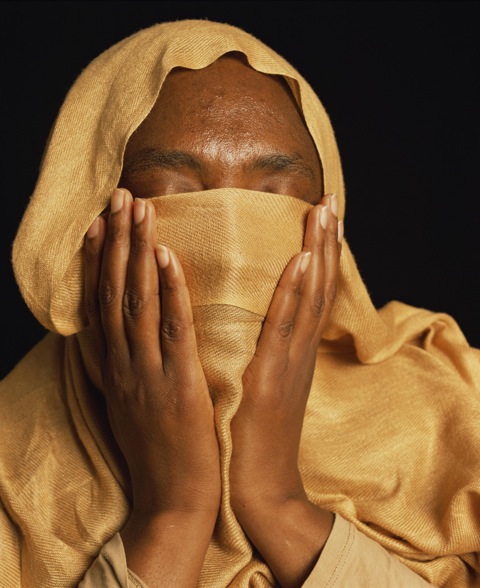

It’s not the same for me as for them. I’m an artist doing my work whereas they went though an unimaginable horror. I’ll never know the pain they suffered and that pain will stay with them forever. Physical wounds may heal but trauma doesn’t. It was thanks to Becky, who arranged meetings with Fatima and The Hooded Men, that I was able to talk with them. I reached out to them as an artist who wanted to know what they went through and give expression to their pain. I talked to The Hooded Men for a while before telling them what I had in mind: that I wanted to take their pictures with black hoods over their heads. It was a shock, they didn’t expect it. And why would they? They assumed I wanted to take a conventional portrait. But they are “The Hooded Men” and that’s who I wanted to photograph. It was not easy for them to revisit that experience. I know it brought back memories they didn’t want to relive. I will forever be grateful that they allowed me to take pictures of them as “The Hooded Men”. Fatima’s portrait came about naturally. She told me she didn’t want to show her face so I suggested partially covering it. I took Polaroids to show her how it would look and she agreed to it. I’m very grateful to her for allowing me to take a beautiful portrait of her.

In one of your Interviews, in which the journalist characterized your work deeply political, you said that you prefer the term “act of conscience”, which is the difference between those two terms in substance and what does this mean for you?

An act of conscience means that that’s how I see it. I don’t need to preach, teach or convert anyone. I don’t call my work political. I prefer if it’s apolitical or politically incorrect. Art does not depend on good manners, only good expression.

The issues that your work is negotiating from the beginning of your career are not easy, after they are touching Religious, Political and Social affairs, which are ingrained in the consciousness for the common sense in a different way, than are approached by contemporary art, what need makes you to deal to them and to express yourself in a way that for someone is shocking?

My work is not shocking to me. It makes sense. You might even call it obvious. I see it in my face and my job is to show it to you in case you haven’t noticed.

Your artworks that are on exhibition at Maison Européenne de la Photographie have as main focus the human, presenting different portraits into two sections. The first part, focuses on the tragedy of September 11 and the dimensions that takes in time…

Sept 11th was a wakeup call. It was the first time America became aware of how much we were hated. It wasn’t our fault. We did nothing to deserve it. It was an attack on innocent people. I did the America portraits to give a face and soul to the people of the Nation. I celebrate all my countrymen and women. I celebrate the human race.

And the second part is negotiating with one of the biggest problems of our time in the urban culture: Τhe lack of housing for many of our fellow human beings. How violent do you consider this social phenomenon is and what could really happen to give an end to it?

The homeless problem and social inequality, the plight of the poor, the underclass and the disenfranchised; it’s a serious problem that has remained unattended for a long time. What happened in England was a sign of things to come. The election of Donald Trump as President of the United States confirms it. France could be next. Bob Dylan said “The Times They Are a Changing.” Malcolm X put it another way: “The pigeons have come home to roost”. The answer to end it is very simple: don’t let the rich and powerful get away with not paying their fair share. The top one hundred corporations in the world do not pay their share of taxes. They hire lawyers, lobbyists, accountants and pay off politicians to change the laws and find the loopholes that allow them to get away with murder. These people should be seen as criminals who have created most of the world’s problems with their greed. It’s not right for the few to have everything and pay nothing to the rest.

First Publication: www.dreamideamachine.com

© Interview-Efi Michalarou

Info: Galerie Nathalie Obadia, 18 rue du Bourg-Tibourg, Paris, Duration: 10/11-30/12/16, Days & Hours: Mon-Sat 11:00-19:00, www.nathalieobadia.com & Maison Européenne de la Photographie, 5/7 Rue de Fourcy, Paris, Duration: 9/11/116-29/1/17, Days & Hours: Wed-Sun 11:00-19:45, www.mep-fr.org