TRACES: Chuck Close

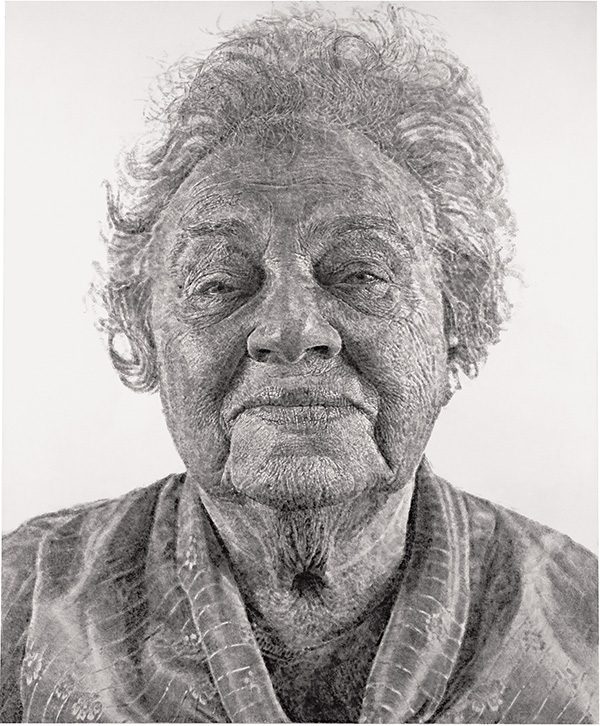

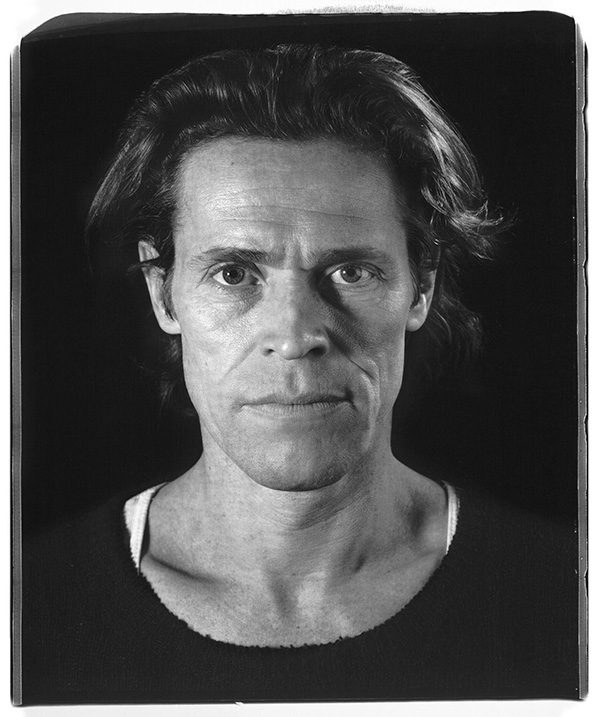

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Chuck Close (5/7/1940-19/8/2021). Chuck Close is renowned for his highly inventive techniques of painting the human face, and is best known for his large-scale, photo-based portrait paintings. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Chuck Close (5/7/1940-19/8/2021). Chuck Close is renowned for his highly inventive techniques of painting the human face, and is best known for his large-scale, photo-based portrait paintings. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

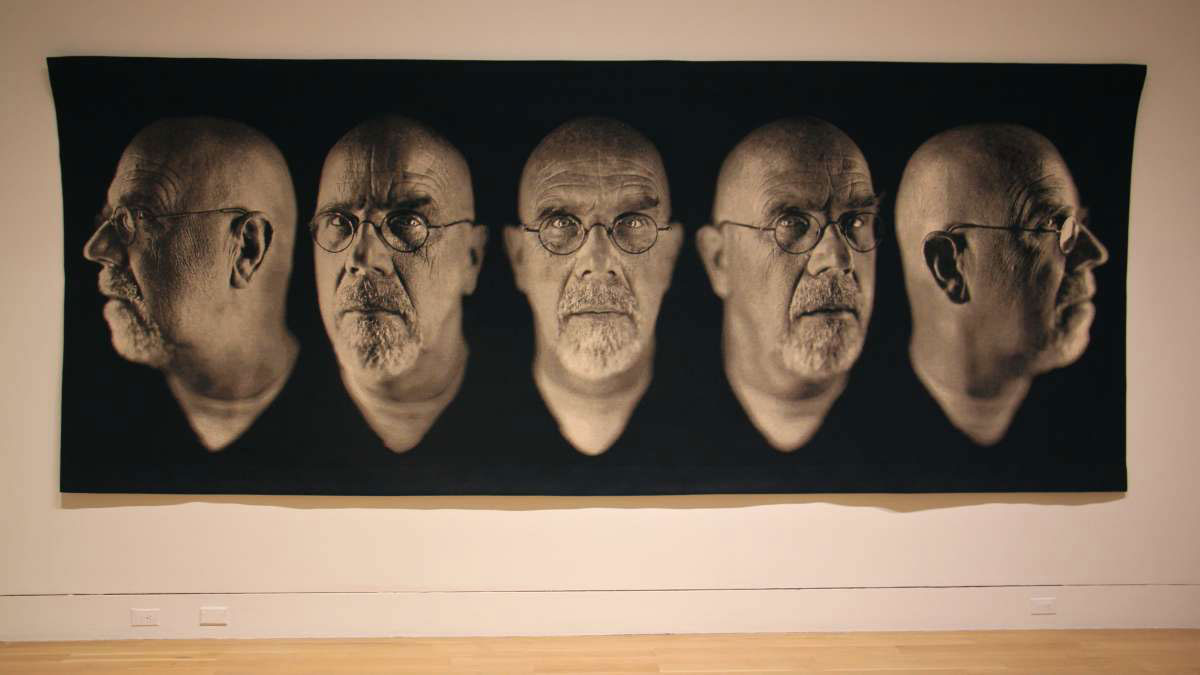

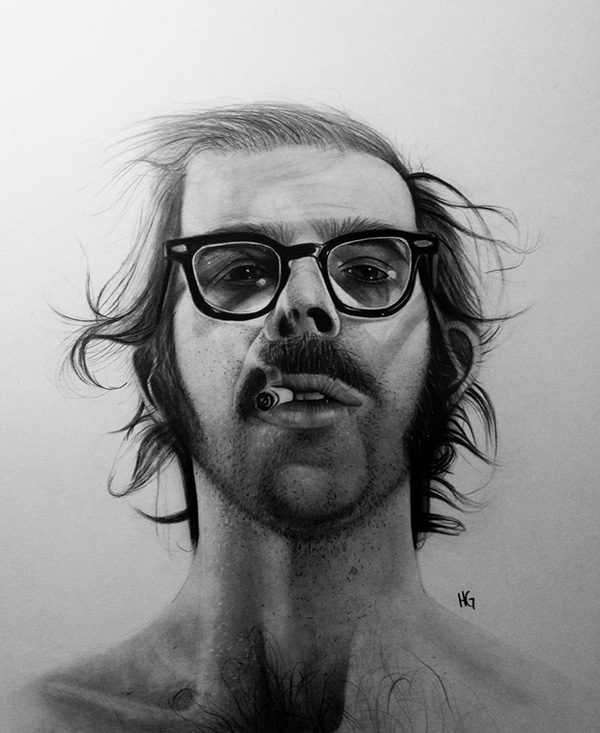

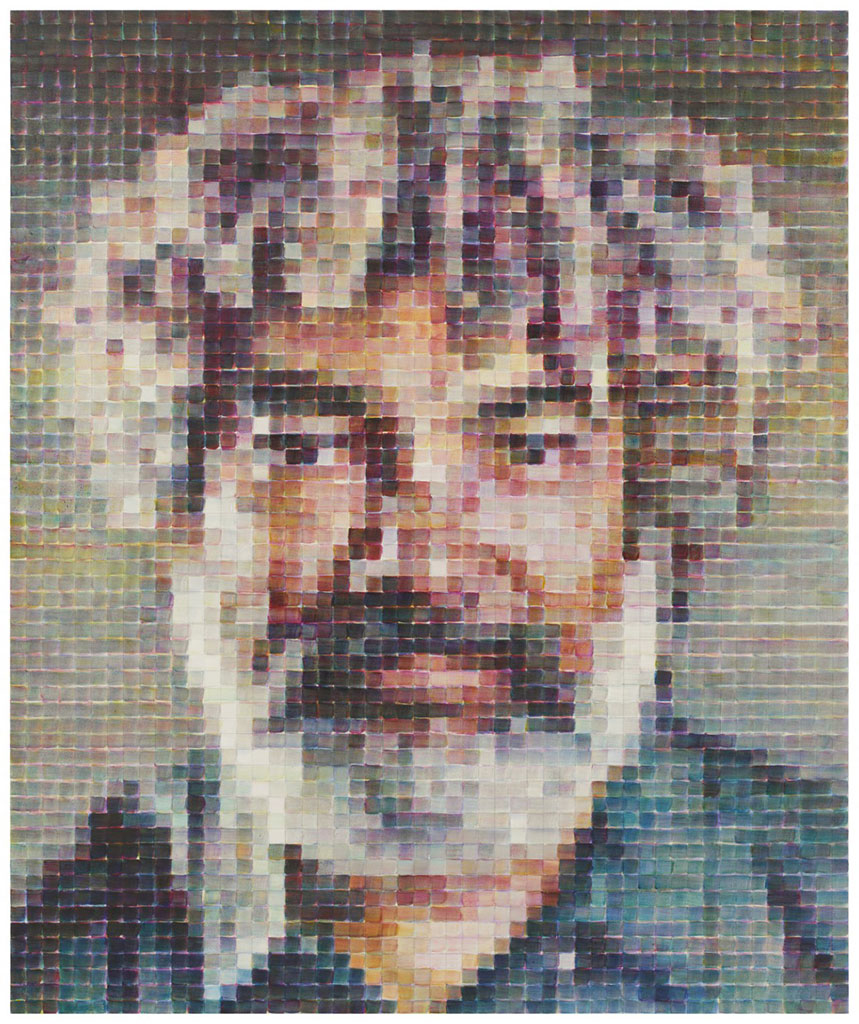

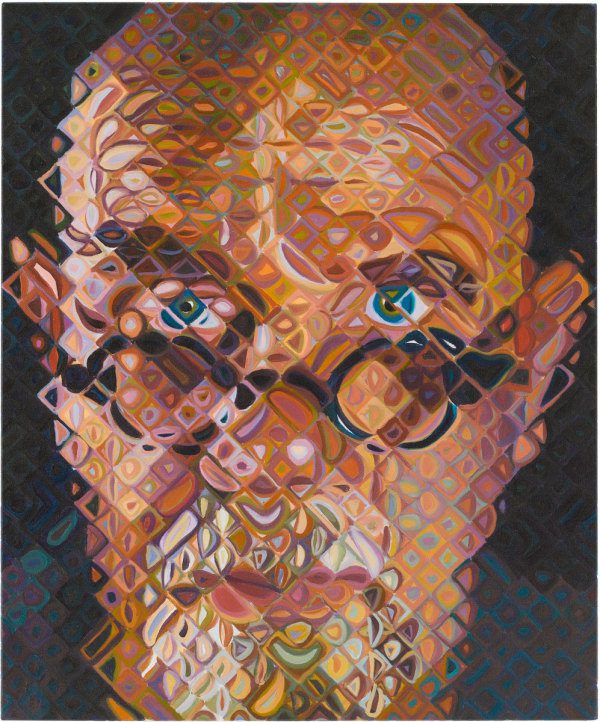

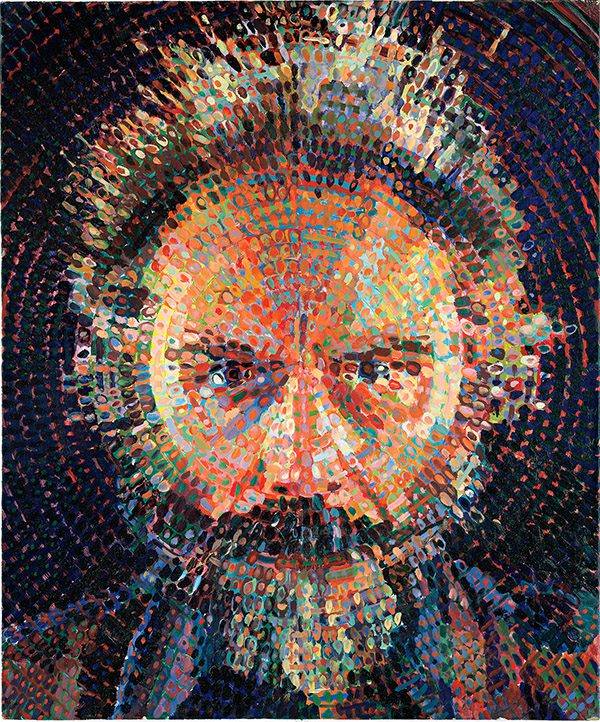

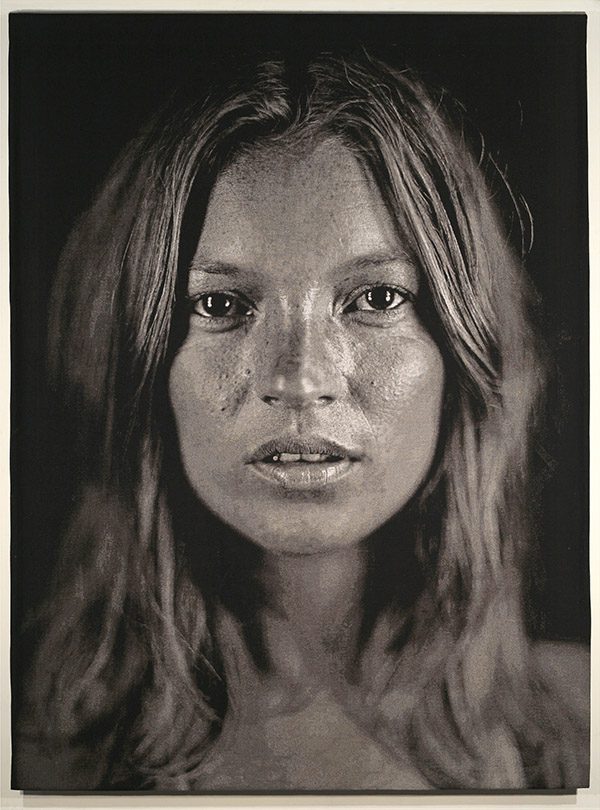

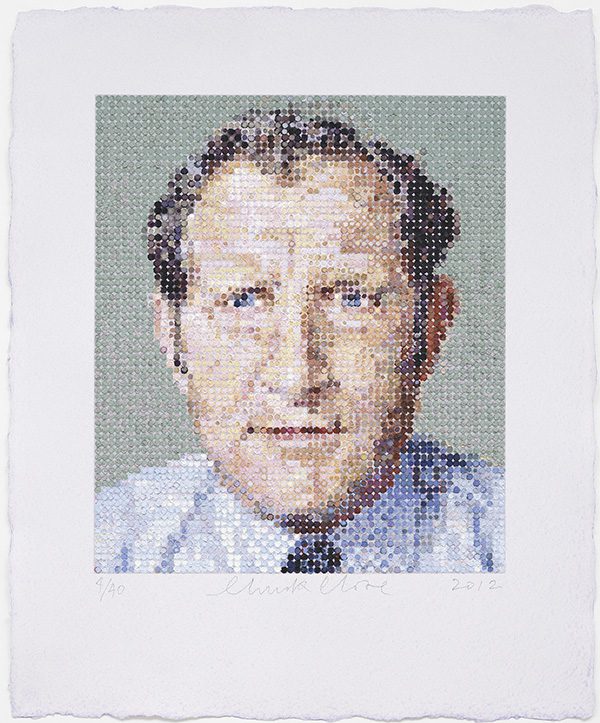

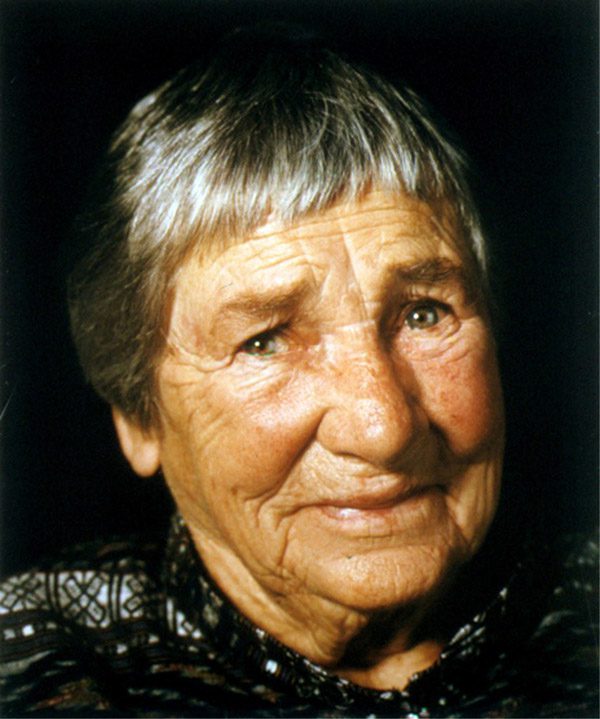

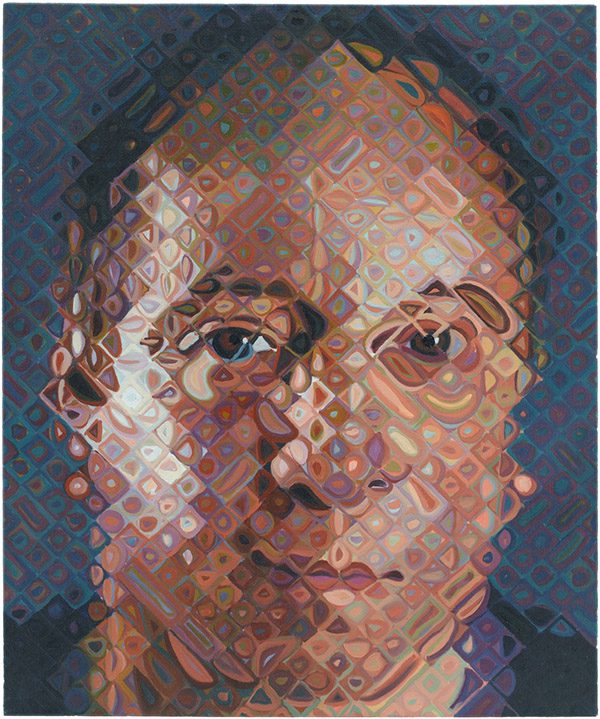

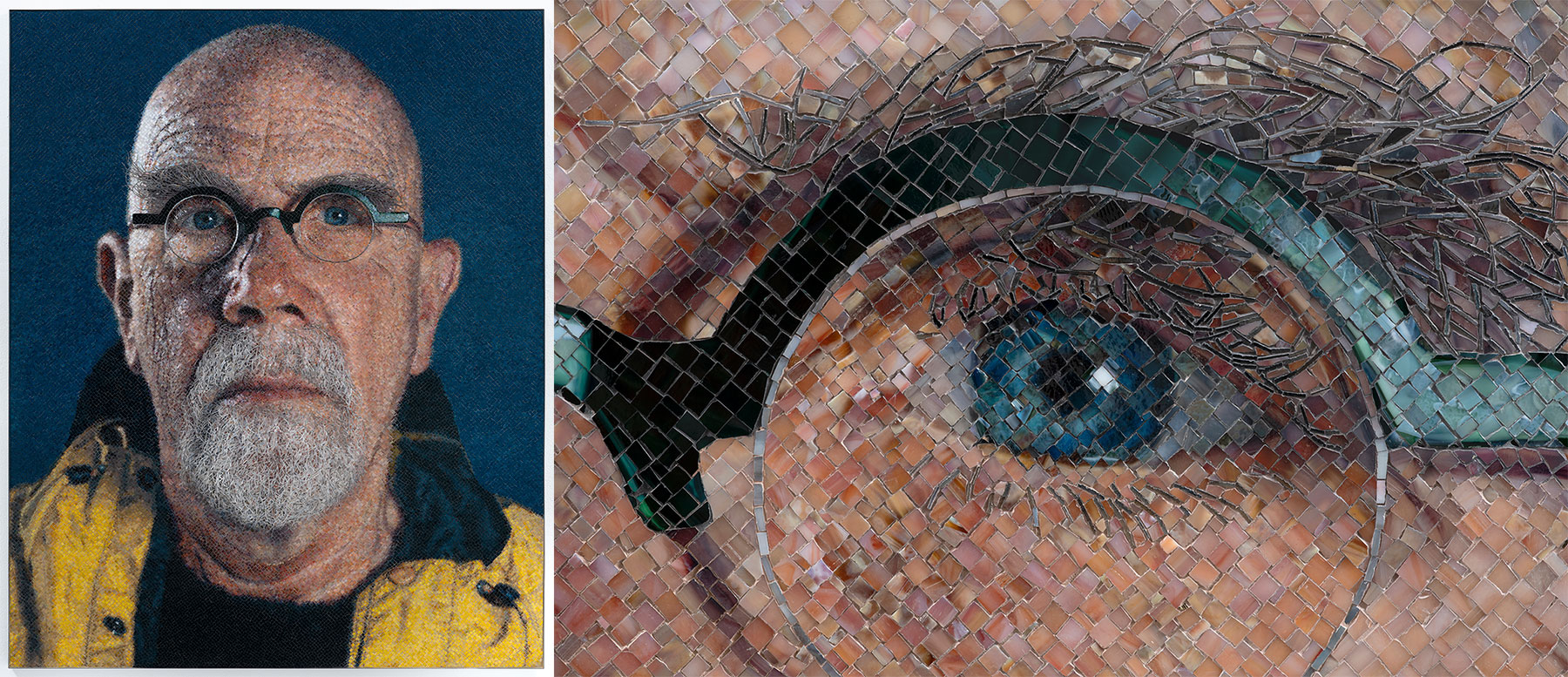

Chuck Close (Charles Thomas Close) had a difficult time with academics due to dyslexia, although teachers were often impressed with his creative approach to projects. He was also diagnosed with facial blindness and a neuromuscular condition that prevented him from engaging in athletics, making the social aspects of school life difficult. While at Yale, Close served as a studio assistant to printmaker Gabor Petardi. In his senior year, Close won a Fulbright scholarship, providing him with the opportunity to study art in Europe. In 1965, deciding that his own Abstract Expressionist style of painting had grown stagnant, he began to experiment with alternative forms and materials. One of his more ambitious ideas of the time involved painting a large nude from a series of photographs, but he set the project aside due to unresolved problems with color and texture. In January 1967, the college held a solo exhibition of other Pop-inspired works by Close, sparking an outrage from the administration due to his use of full-frontal nude male images. The American Civil Liberties Union defended Close in the resulting lawsuit, brought on by the university president, John Lederle. Ultimately, the ruling was in favor of the university, a decision that effectively ended his time in Amherst. Close’s search for a signature style was a persistent frustration to him, and with his wife support, he continued to experiment with different styles. Working again from photographs, he parsed the image into a grid, which he then transferred onto the canvas. Painstakingly hand-copying the photograph’s gridded segments onto each corresponding cube of the canvas, Close built a larger-than-life, black and white copy of the female nude’s image. The resulting “Big Nude” (1967), reads as both an abstract and a figurative painting. Close’s career gained momentum from the sale of a similarly conceived “Big Self-Portrait” (1967-68) to the Walker Art Museum in 1969. Motivated by the newly-developed method of painting, he sought to refine his technique in his first “Heads” series. Also in black and white, these paintings emphasized their photographic roots. In 1969 before his first New York City group exhibition, writer Cindy Nemser conducted an interview with Close for the January 1970 issue of Artforum magazine, which accidentally published his name as “Chuck Close.” The artist subsequently adopted it as a professional moniker from that time to the present. Close developed a method that utilized separate layers of cyan, magenta and yellow. Painted on top of each other, the colors compel the eye of the observer to mix them in order to arrive at a realistic, full-color image. The first portrait executed by this method was “Kent” (1970-71), which took Close almost a full year to complete. He spent the next several years working on three-color-process portraits. In the summer of 1972, Parasol Press invited Close to produce a series of prints by any method he desired. Intrigued, Close chose the mezzotint, a virtually abandoned printmaking technique common to 18th Century portrait reproductions. Reproducing an already gridded photograph of Keith Hollingworth, the print unintentionally revealed the schematic checkerboard pattern. These unexpected results led to a Close repeated use of the same photographs for paintings executed via different techniques and in various media. In December 1988, Close suffered from intense chest pains that led to complete paralysis below the neck, a watershed moment in his life that the artist refers to as “The Event”. With the dedication of his wife, who insisted that his physical therapy focus on the act of painting, Close was able to regain enough movement and control in his upper body to allow him to continue working. Close has since built a studio to accommodate his wheelchair and a two-storey, remote-control easel, where he continues to dynamically develop his artistic processes with the help of studio assistants. Utilizing the modern computer-aided methods of tapestry, Close is now able to approximate, in woven images, the mirror-like illusionism characteristic of the 19th Century photographic glass daguerreotype. As if coming full circle, Close may be said to have reinvigorated the genre of Photorealism just when everyone had assumed it had been relegated to history.

Chuck Close (Charles Thomas Close) had a difficult time with academics due to dyslexia, although teachers were often impressed with his creative approach to projects. He was also diagnosed with facial blindness and a neuromuscular condition that prevented him from engaging in athletics, making the social aspects of school life difficult. While at Yale, Close served as a studio assistant to printmaker Gabor Petardi. In his senior year, Close won a Fulbright scholarship, providing him with the opportunity to study art in Europe. In 1965, deciding that his own Abstract Expressionist style of painting had grown stagnant, he began to experiment with alternative forms and materials. One of his more ambitious ideas of the time involved painting a large nude from a series of photographs, but he set the project aside due to unresolved problems with color and texture. In January 1967, the college held a solo exhibition of other Pop-inspired works by Close, sparking an outrage from the administration due to his use of full-frontal nude male images. The American Civil Liberties Union defended Close in the resulting lawsuit, brought on by the university president, John Lederle. Ultimately, the ruling was in favor of the university, a decision that effectively ended his time in Amherst. Close’s search for a signature style was a persistent frustration to him, and with his wife support, he continued to experiment with different styles. Working again from photographs, he parsed the image into a grid, which he then transferred onto the canvas. Painstakingly hand-copying the photograph’s gridded segments onto each corresponding cube of the canvas, Close built a larger-than-life, black and white copy of the female nude’s image. The resulting “Big Nude” (1967), reads as both an abstract and a figurative painting. Close’s career gained momentum from the sale of a similarly conceived “Big Self-Portrait” (1967-68) to the Walker Art Museum in 1969. Motivated by the newly-developed method of painting, he sought to refine his technique in his first “Heads” series. Also in black and white, these paintings emphasized their photographic roots. In 1969 before his first New York City group exhibition, writer Cindy Nemser conducted an interview with Close for the January 1970 issue of Artforum magazine, which accidentally published his name as “Chuck Close.” The artist subsequently adopted it as a professional moniker from that time to the present. Close developed a method that utilized separate layers of cyan, magenta and yellow. Painted on top of each other, the colors compel the eye of the observer to mix them in order to arrive at a realistic, full-color image. The first portrait executed by this method was “Kent” (1970-71), which took Close almost a full year to complete. He spent the next several years working on three-color-process portraits. In the summer of 1972, Parasol Press invited Close to produce a series of prints by any method he desired. Intrigued, Close chose the mezzotint, a virtually abandoned printmaking technique common to 18th Century portrait reproductions. Reproducing an already gridded photograph of Keith Hollingworth, the print unintentionally revealed the schematic checkerboard pattern. These unexpected results led to a Close repeated use of the same photographs for paintings executed via different techniques and in various media. In December 1988, Close suffered from intense chest pains that led to complete paralysis below the neck, a watershed moment in his life that the artist refers to as “The Event”. With the dedication of his wife, who insisted that his physical therapy focus on the act of painting, Close was able to regain enough movement and control in his upper body to allow him to continue working. Close has since built a studio to accommodate his wheelchair and a two-storey, remote-control easel, where he continues to dynamically develop his artistic processes with the help of studio assistants. Utilizing the modern computer-aided methods of tapestry, Close is now able to approximate, in woven images, the mirror-like illusionism characteristic of the 19th Century photographic glass daguerreotype. As if coming full circle, Close may be said to have reinvigorated the genre of Photorealism just when everyone had assumed it had been relegated to history.