TRACES: Carmen Herrera

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Carmen Herrera (31/5/1915-12/2/2022 ), she has been painting since her youth in Cuba, but it was only in the last few years that she found recognition and her work is now acknowledged as a precursor to many modernist styles: Minimalism, Geometric and Modernist Abstraction, and Concrete Painting. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Carmen Herrera (31/5/1915-12/2/2022 ), she has been painting since her youth in Cuba, but it was only in the last few years that she found recognition and her work is now acknowledged as a precursor to many modernist styles: Minimalism, Geometric and Modernist Abstraction, and Concrete Painting. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

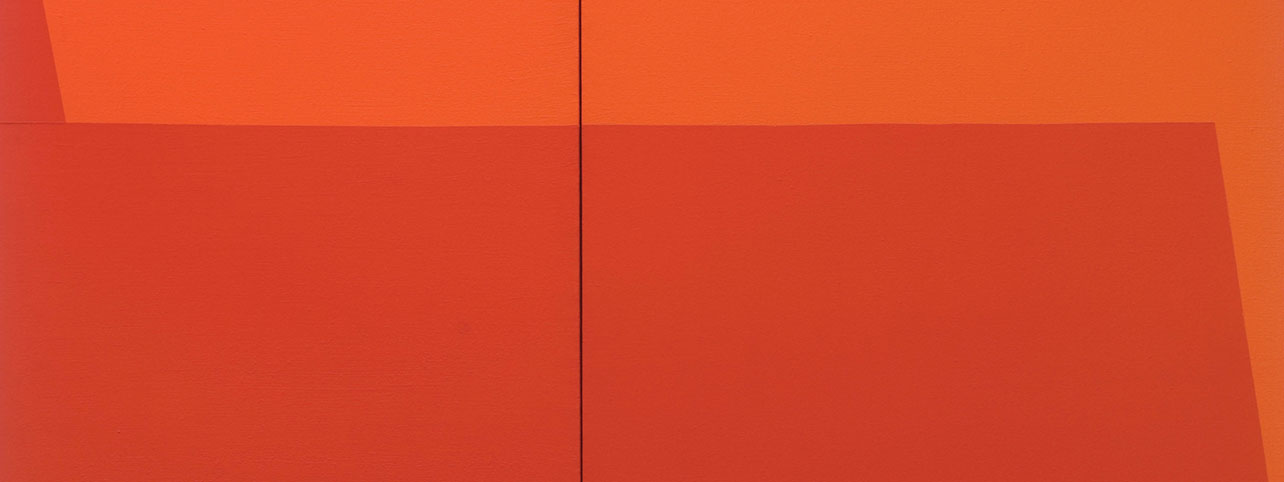

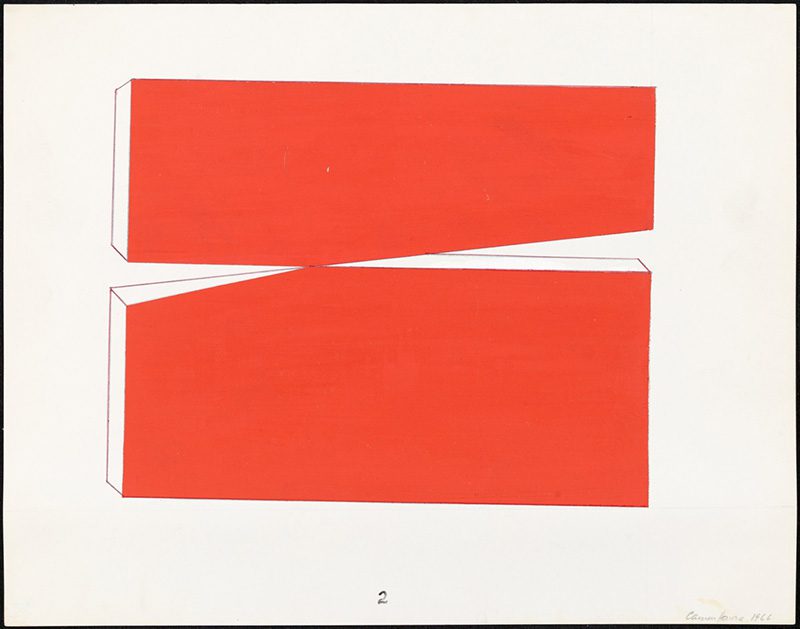

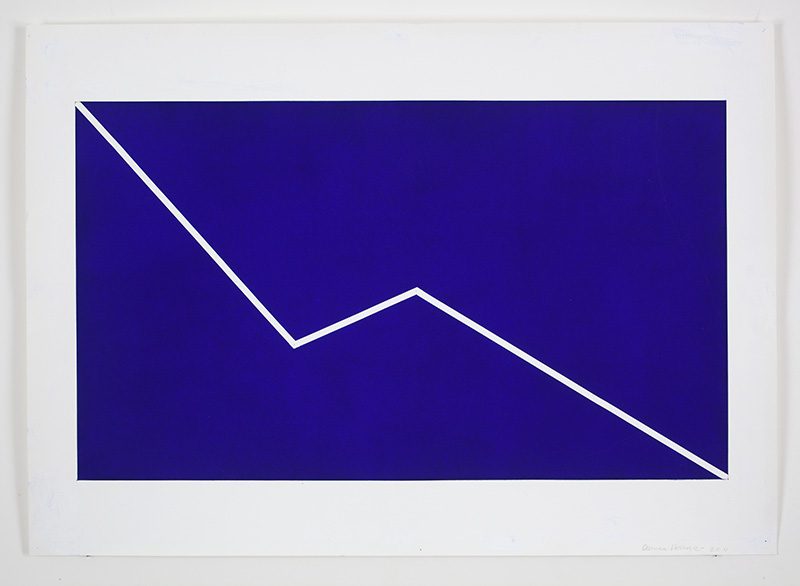

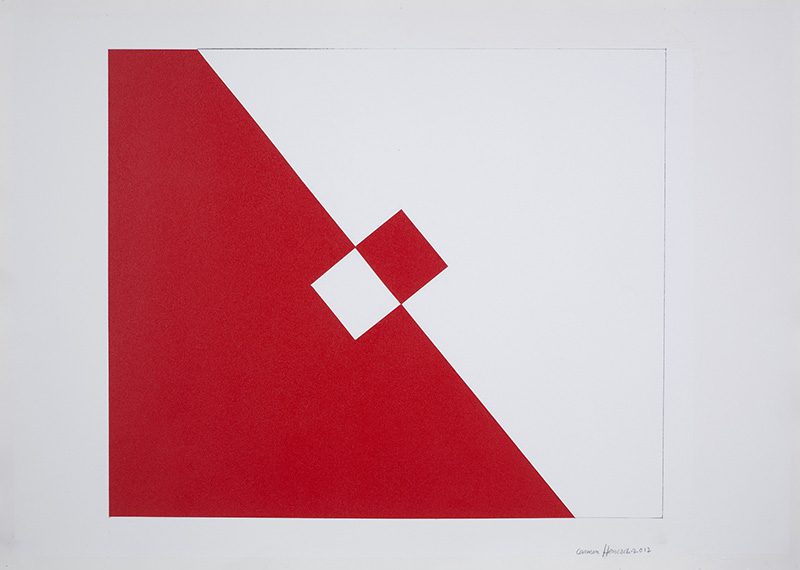

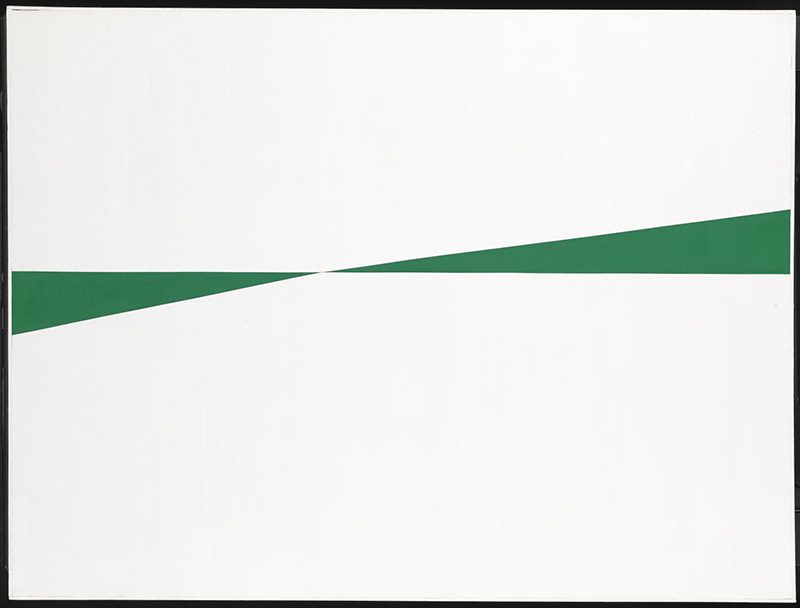

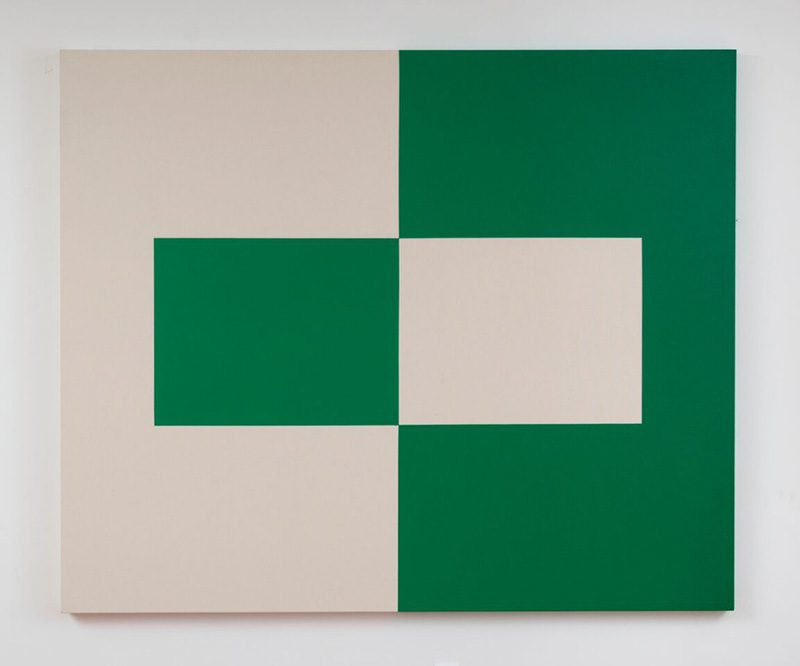

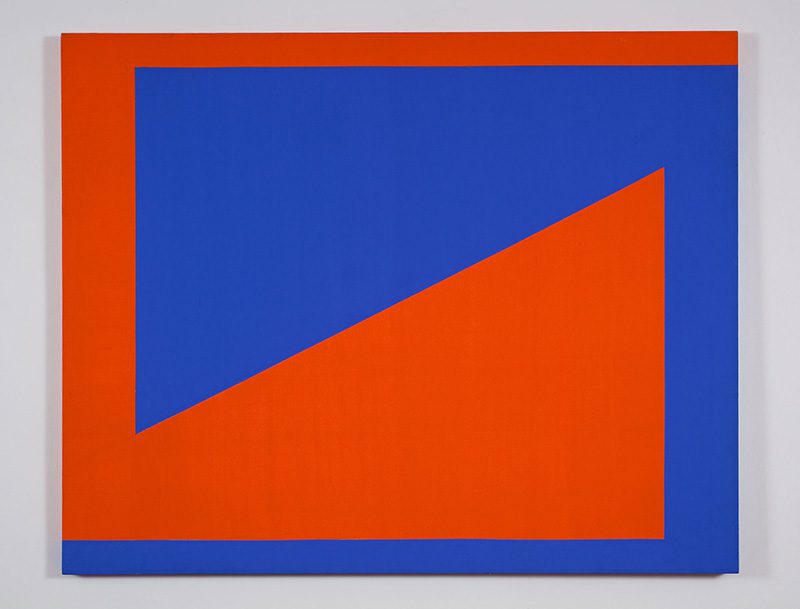

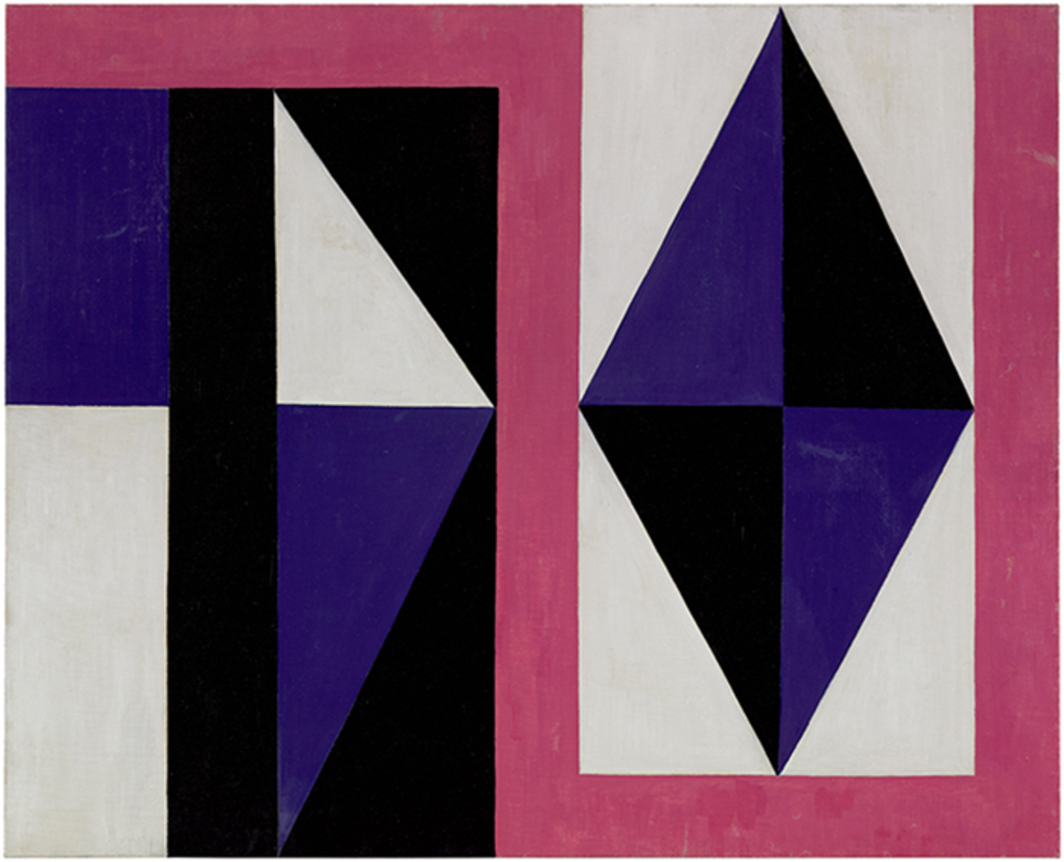

Carmen Herrera was raised by intellectual parents in Havana. She took art lessons when she was young, and as a teenager she was sent to Paris to further her studies. Upon her return to Cuba, she made sculptures of wood and later began studying for an architecture degree at the University of Havana, though the tumultuous political situation in the country following Fulgencio Batista’s seizure of power prevented her from finishing. She relocated in 1939 to New York City, where she pursued mostly figurative painting at the Art Students League and struck up friendships with other artists, including Barnett Newman. Only after returning to Paris in 1948, however, did Herrera fully develop her artistic identity, finding inspiration from the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, an art collective striving to challenge the traditions of the art scene, who mounted an annual exhibition featuring Abstract, mostly nonrepresentational work by figures such as Josef Albers and Jean Arp. Reducing her formal vocabulary to its essential elements, Herrera started creating paintings in which boldly coloured, sharply defined geometric shapes predominated, and she exhibited this new work through the salon in 1949–52. In 1954 Herrera settled permanently in New York City. Though she continued to produce strong work throughout the ‘50s, particularly the beginning of a series of stark black-and-white paintings, she failed to attain the same recognition accorded her peers. The prejudices some gallery owners held against women and Latin American artists put her at a disadvantage, as did the fact that her work, some of which prefigured the later trends of Op art and Hard-edged Minimalism, was out of step with the period’s fashion for Abstract Expressionism. Moreover, Herrera herself cared little for fame during this time, preferring to concentrate on painting rather than publicity. Herrera continued her precise chromatic explorations in the ‘60s and ’70s in works such as “Blanco y verde” (1966), a triangular sliver of green against an austere white field, and “Saturday” (1978), a jet-black canvas interrupted by a thick gold zigzag. She also demonstrated an interest in pushing beyond painting’s traditional structural limitations. Since her days in Paris, she had experimented with nonrectangular canvases, and she played with dimensionality in works such as “Amarillo” (1971), painted on four-inch plywood. In 1984, after years of exhibiting only sporadically, Herrera received her first retrospective, at the Alternative Museum in New York City. Still, she did not sell a single painting until two decades later when, at age 89, she was included in a show of women geometric painters at New York City’s latincollector gallery. From then on, her art-world stock skyrocketed. Her works were acquired for the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., and Tate Modern in London, and she won accolades for several solo exhibitions. A 29-minute documentary on Herrera, The 100 Years Show by Alison Klayman, was released in 2015.

Carmen Herrera was raised by intellectual parents in Havana. She took art lessons when she was young, and as a teenager she was sent to Paris to further her studies. Upon her return to Cuba, she made sculptures of wood and later began studying for an architecture degree at the University of Havana, though the tumultuous political situation in the country following Fulgencio Batista’s seizure of power prevented her from finishing. She relocated in 1939 to New York City, where she pursued mostly figurative painting at the Art Students League and struck up friendships with other artists, including Barnett Newman. Only after returning to Paris in 1948, however, did Herrera fully develop her artistic identity, finding inspiration from the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, an art collective striving to challenge the traditions of the art scene, who mounted an annual exhibition featuring Abstract, mostly nonrepresentational work by figures such as Josef Albers and Jean Arp. Reducing her formal vocabulary to its essential elements, Herrera started creating paintings in which boldly coloured, sharply defined geometric shapes predominated, and she exhibited this new work through the salon in 1949–52. In 1954 Herrera settled permanently in New York City. Though she continued to produce strong work throughout the ‘50s, particularly the beginning of a series of stark black-and-white paintings, she failed to attain the same recognition accorded her peers. The prejudices some gallery owners held against women and Latin American artists put her at a disadvantage, as did the fact that her work, some of which prefigured the later trends of Op art and Hard-edged Minimalism, was out of step with the period’s fashion for Abstract Expressionism. Moreover, Herrera herself cared little for fame during this time, preferring to concentrate on painting rather than publicity. Herrera continued her precise chromatic explorations in the ‘60s and ’70s in works such as “Blanco y verde” (1966), a triangular sliver of green against an austere white field, and “Saturday” (1978), a jet-black canvas interrupted by a thick gold zigzag. She also demonstrated an interest in pushing beyond painting’s traditional structural limitations. Since her days in Paris, she had experimented with nonrectangular canvases, and she played with dimensionality in works such as “Amarillo” (1971), painted on four-inch plywood. In 1984, after years of exhibiting only sporadically, Herrera received her first retrospective, at the Alternative Museum in New York City. Still, she did not sell a single painting until two decades later when, at age 89, she was included in a show of women geometric painters at New York City’s latincollector gallery. From then on, her art-world stock skyrocketed. Her works were acquired for the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., and Tate Modern in London, and she won accolades for several solo exhibitions. A 29-minute documentary on Herrera, The 100 Years Show by Alison Klayman, was released in 2015.