PRESENTATION: Peter Halley-Paintings from the 1980s

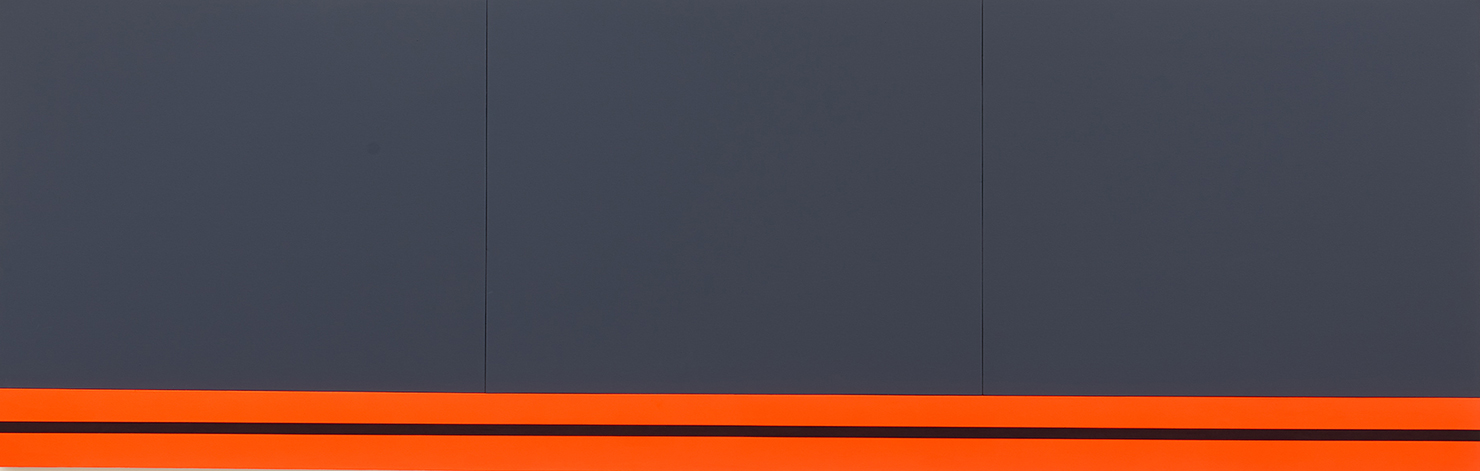

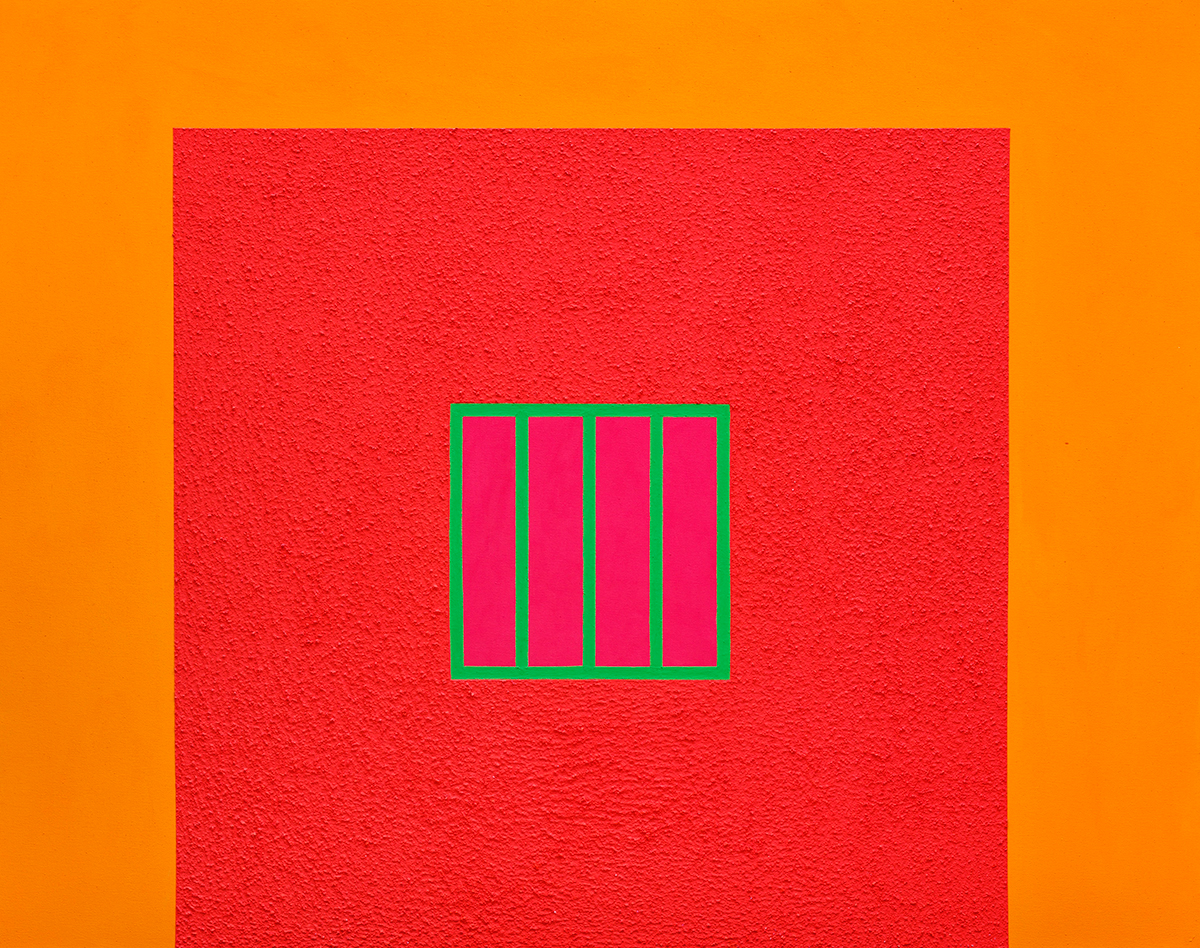

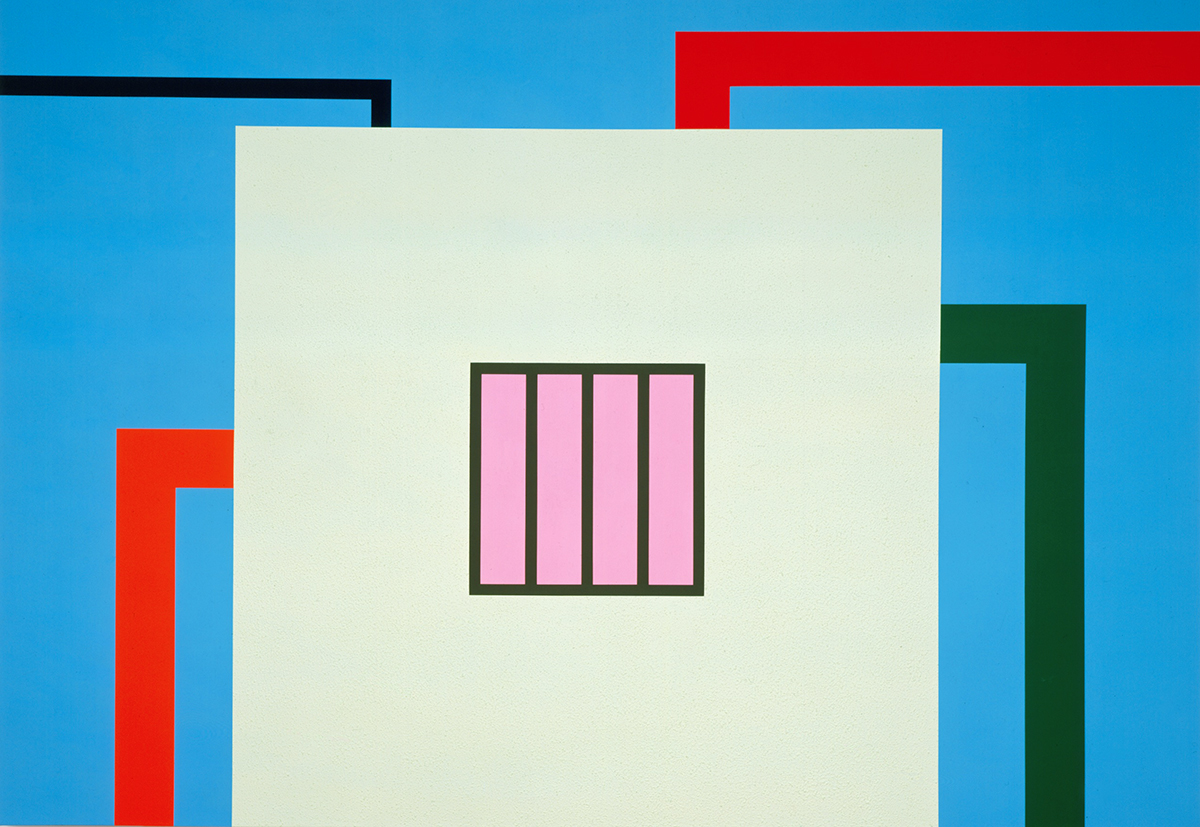

Peter Halley’s art is set on Constructivist Colour Field Painting, the composition of his pictures being based on the relationship between – mostly rectangular – forms and the color fields. As a third element, he adds various color qualities and surfaces to his repertoire of forms, for instance by using neon and industrial colors or mixing sand or other particles into his paint, adding a three-dimensional relief-quality to his works. Peter Halley’s work have been classified as Postmodern Concrete Art and Neo-Geo Art. In terms of content, however, Halley refers to our contemporary semiotic system and forms of communication, especially to digital code systems such as the Internet or circuit diagrams.

Peter Halley’s art is set on Constructivist Colour Field Painting, the composition of his pictures being based on the relationship between – mostly rectangular – forms and the color fields. As a third element, he adds various color qualities and surfaces to his repertoire of forms, for instance by using neon and industrial colors or mixing sand or other particles into his paint, adding a three-dimensional relief-quality to his works. Peter Halley’s work have been classified as Postmodern Concrete Art and Neo-Geo Art. In terms of content, however, Halley refers to our contemporary semiotic system and forms of communication, especially to digital code systems such as the Internet or circuit diagrams.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Mudam Archive

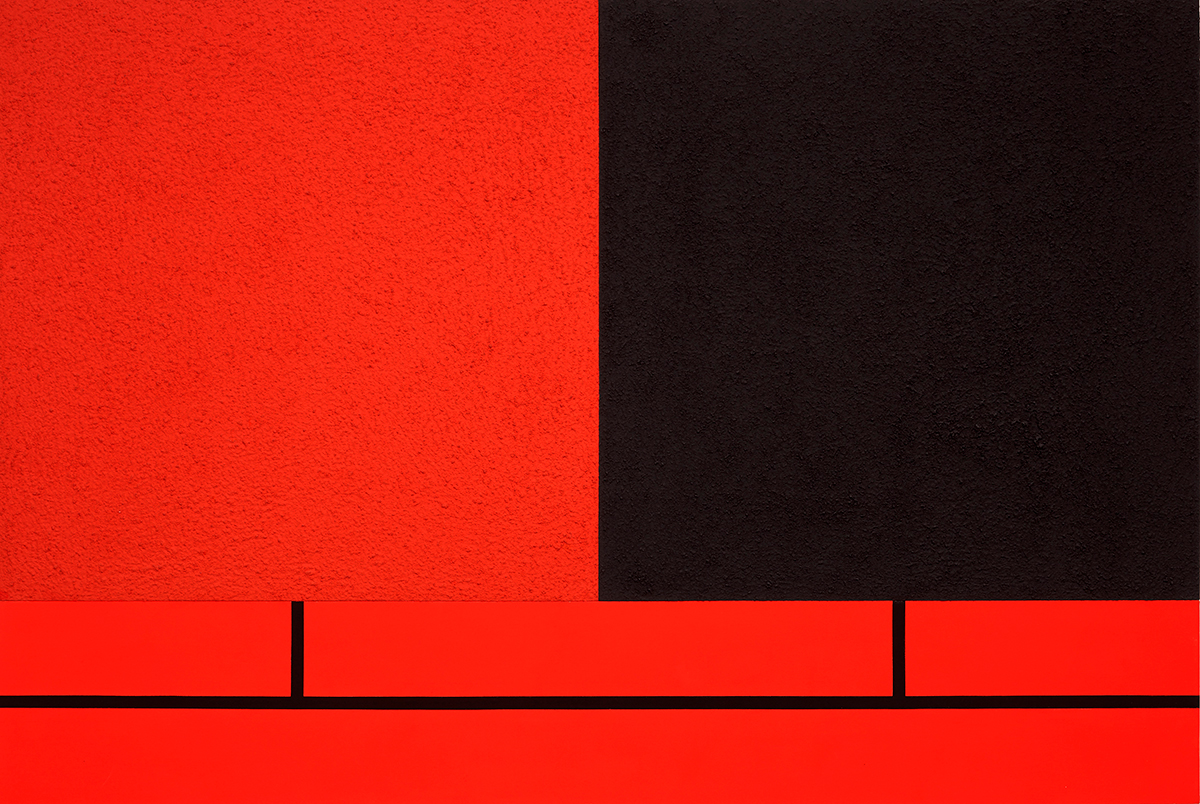

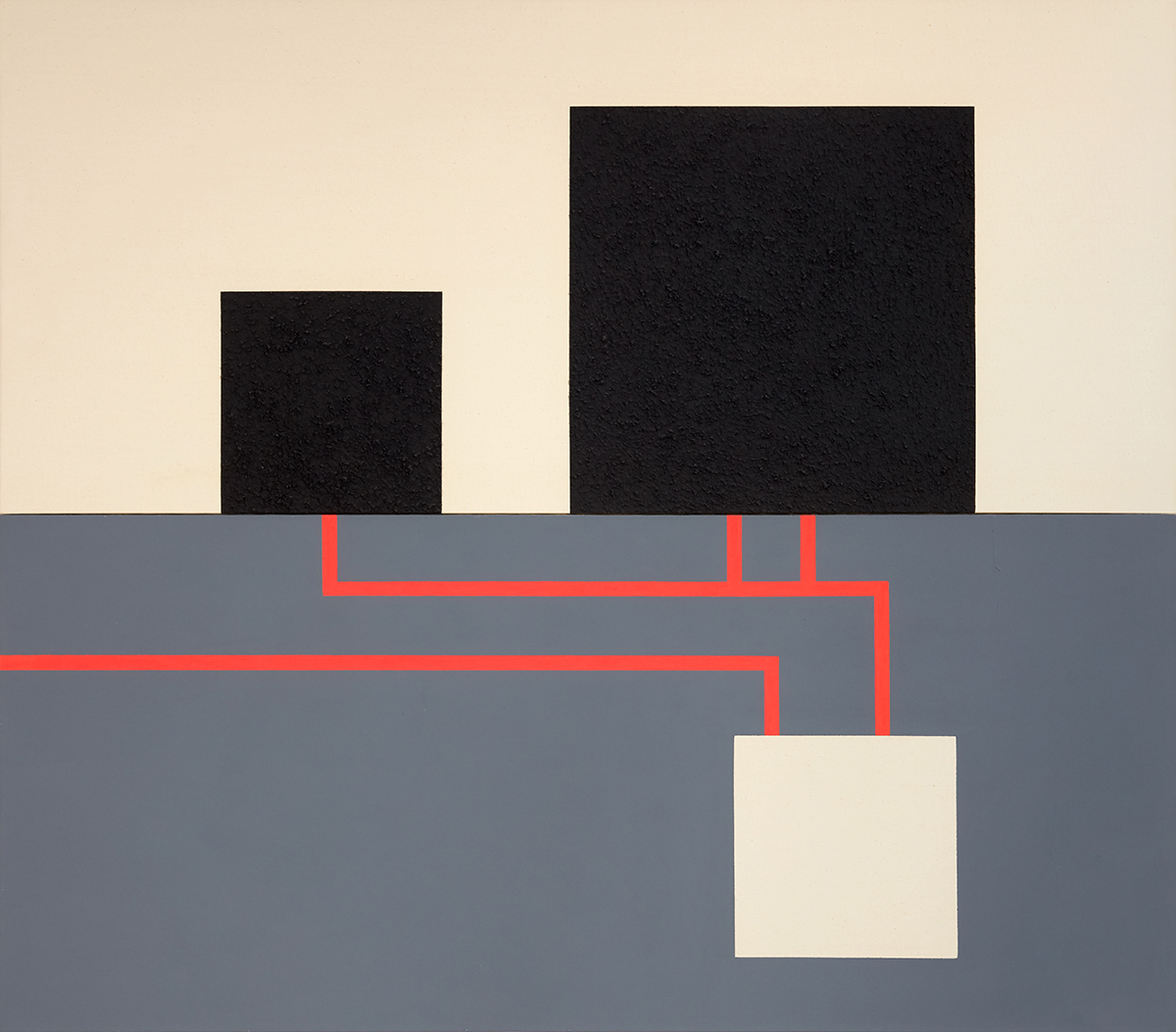

With thirty key works from public and private collections, the retrospective “Paintings from the 1980s” presents paintings alongside previously unseen drawings, sketches and notes from the first decade of Peter Halley’s career. During the 1980s Peter Halley developed a signature vocabulary that he has used in his work now for over forty years. Redeploying the language of geometric abstraction, he produced diagrammatic paintings representing social subjects. With these works he addressed issues that are fundamental to art produced over the last two centuries: namely, urbanisation and industrialisation, considering their impact and legacies within a post-industrial society marked by technological change. The vocabulary that Halley developed in the early 1980s borrowed loosely but visibly from the history of twentieth-century geometric abstract art: from the square forms used by Kazimir Malevich or Josef Albers to the grids of Piet Mondrian; from the expanses of raw canvas and color fields of Mark Rothko to the bands of color that Barnett Newman ‘zipped’ across his canvases. Similarly, from minimalism Halley adopted the use of industrial tools and materials; applying paint with rollers (instead of brushes) and using Roll-a-Tex and Day-Glo for their respective readymade texture and manufactured color. While this approach enabled Halley to address the subject of painting and its history within his work, it was also symptomatic of a wider trend in cultural and philosophical discourse that from 1980 was referred to as ‘intertextuality’. Prints: Halley produced a series of prints on Kodalith photographic film, a material used for graphic art work. The dense black tones achieved with this photographic negative enabled Halley to produce a high contrast print that renders the text as a clear mylar ‘window’, which is set in front of a white matt board. These works reproduce words or phrases that were collected from a range of sources including advertising, album sleeves, ATM screens and road signs. Collectively they explore modes of receiving and processing energy and information by isolating fragments of language. They can also be linked to Halley’s influential writing from the 1980s, which provided an important critical context for his paintings and the work of his peers.

Drawings: Throughout the 1980s, Halley used a pen or pencil on gridded paper to set down his compositional ideas. In 1981 he produced a series of larger, formally composed works on graph paper. Unlike his spontaneous studies, these are carefully drawn with a drafting pen and ink and were made to document the initial development of his vocabulary. Drawings such as “Kinds of Prisons”, “Prisons – Inside and Outside”, “Houses with Windows” and “Prisons, Windows” are closely linked to the paintings Halley made in 1980 and 1981, after he moved back to New York after living in New Orleans for several years. These works also contain reflections of earlier works and show the influence of the paintings of Philip Guston and conversely, reflect the architectures and designs of the Memphis Group. Areas of pattern, and in particular the use of dots also denote a gendered idea of geometry Paintings: The “Grave” (1980), the first painting in this exhibition, was made later that year. It is one of a number of works from 1980 and 1981 that imply a human subject via an idea of loss or death and entombment using geometric form. Early in 1981 Halley arrived at the ‘prison’ as a motif. By 1981 the objects of confinement were connected by lines or ‘conduits’, with which he alludes to the networks of pipes, ducts and cables that supply us with water, air, energy and information. “Prison with Conduit” (1981) incorporates three important innovations in Halley’s vocabulary: it is the first painting to be made on two attached panels, the first to employ Day-Glo color and the first to feature a ‘conduit’. While the prison figures confinement, the conduit diagrams connection. By 1982, the subject of confinement or enclosure was also figured with a ‘cell’, a monochrome square painted with Roll-a-Tex. The choice of this term is also significant, a cell referring on the one hand to an architectural entity but also to a source of energy (in a battery) or a unit of data storage (in a computer). In the 1982 paintings “Red Cell with Conduit” and “Glowing and Burnt-Out Cells with Conduit colour” is used to imply the presence or absence of energy. Halley’s paintings of the mid-1980s often depict prisons, cells and conduits on black backgrounds, echoing the aesthetics of the first generations of home video game consoles. The subject of alienation and social isolation figures iconographically in these paintings but also with a degree of humour. The 1985 painting “Prison and Cell with Smokestack and Conduit” draws equivalences between ideas of imprisonment and freedom, while the prison in “Yellow Prison with Underground Conduit” is completely cut adrift by its conduit. “Prison”, “Asynchronous Terminal”, “Partial Grounding” and “A Monstrous Paradox” (all 1989) foreground the work that Halley would continue in the 1990s and subsequent decades. By the end of the decade the compositions began to anticipate an era of hyperconnectivity; conduits became manifold, painted with different colors, thicknesses and extending in different directions, embodying a new-found ‘absurdity’ in the techno-social moment.

Photo: Peter Halley, Prison, 1989, Acrylic, fluorescent acrylic, and Roll-a-Tex on canvas, One panel, Collection CAPC musée d’Art contemporain, Bordeaux, © Photo: Steven Sloman

Info: Curator: Michelle Cotton, Assistant Curator: Sarah Beaumont, Mudam Luxembourg-Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, 3 Park Dräi Eechelen, Luxembourg-Kirchberg, Duration: 31/3-15/10/2023, Days & Hours: Mon & Thu-Sun 19:00-18:00, Wed 10:00-21:00, www.mudam.com/