ART-PRESENTATION: Agitprop!

Most art is political, whether it means to be or not. At key moments in history, artists have reached beyond galleries and museums, using their work as a call to action to create political and social change. The term Agitprop, named for its combination of the Russian words “Agitatsiya” and “Propaganda”, uses art as a vehicle for social and political change. The twin strategies of agitation and propaganda were originally elaborated by the Marxist theorist Georgy Plekhanov.

Most art is political, whether it means to be or not. At key moments in history, artists have reached beyond galleries and museums, using their work as a call to action to create political and social change. The term Agitprop, named for its combination of the Russian words “Agitatsiya” and “Propaganda”, uses art as a vehicle for social and political change. The twin strategies of agitation and propaganda were originally elaborated by the Marxist theorist Georgy Plekhanov.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Brooklyn Museum Archive

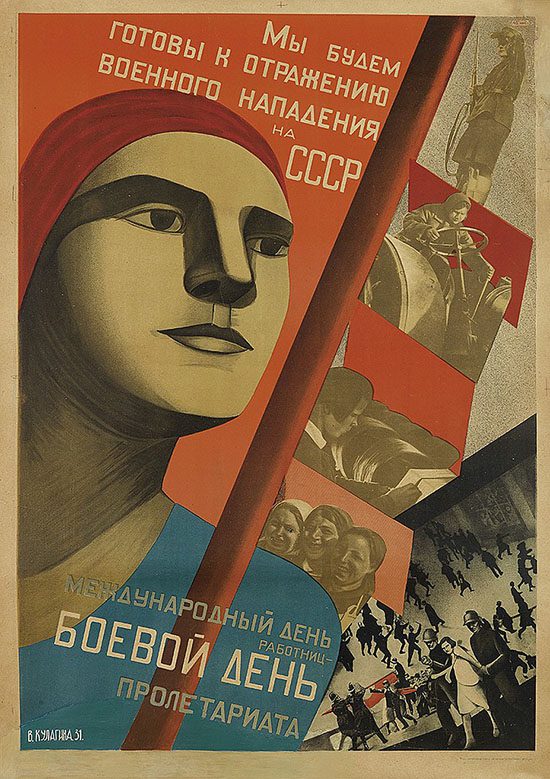

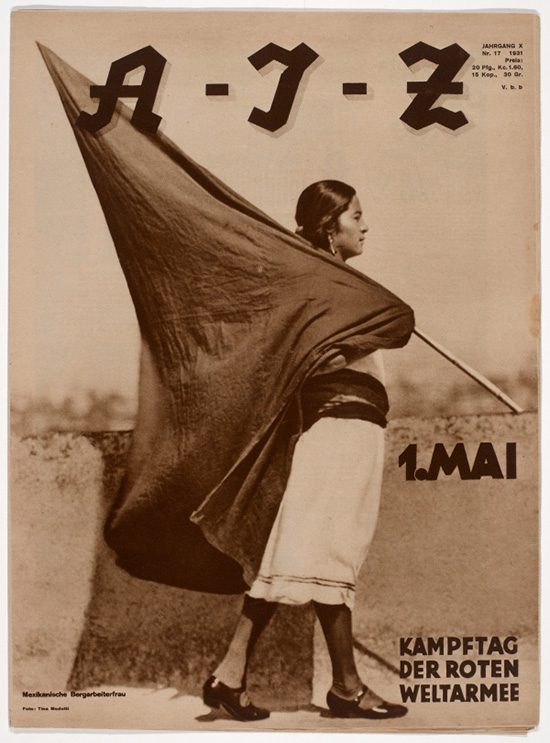

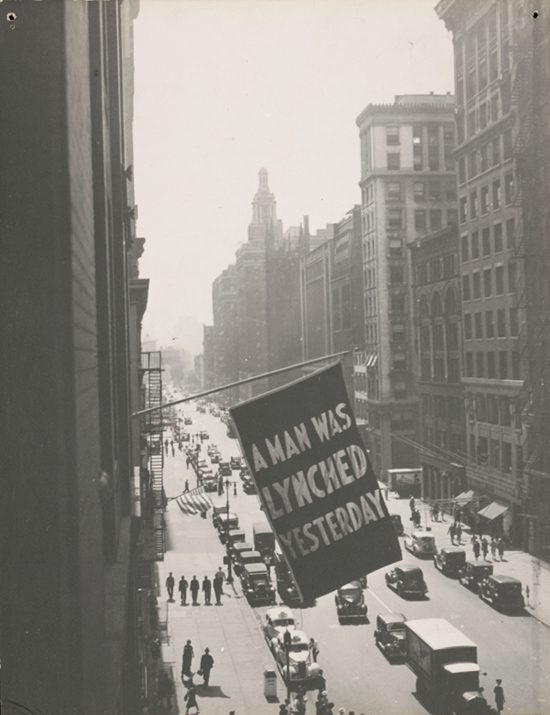

Since that time, artists across the ideological and global landscape have adopted modes of expression that can be widely reproduced and disseminated. The exhibition “Agitprop” at the Brooklyn Museum explores the supreme political art form of the 20th Century, the one that most totally captured the chaos and upheaval of an age of extremes, ranging from revolutionary Russia to Hitler’s Germany, from the battlefields of Spain’s civil war to New Deal America. The exhibition features a full range of these materials, from photography and film to prints and banners to street actions and songs, TV shows, social media, and performances. Connecting current creative practices with strategies from the early 20th Century, these projects show artists responding to the pressing questions of their day and seeking to motivate broad, diverse audiences. The Brooklyn exhibition has change built in. It’s been conceived as an exhibition in progress, and at this point, early in its run, it looks like one, only half-there and thin. But there’s more, it will gradually fill out in three successive, cumulative stages. The first, up now, has both historical material and works by contemporary artists. These artists will choose the participants for the next stage, which opens in February, and the February group will pick the artists for the third stage, coming in April. The historical works, which will be on view throughout, is in five distinct sections and looks back to the start of the 20th century when agitprop, was developing as an art genre. The most familiar examples here are Russian posters campaigning for women’s rights. In the earliest, from 1917, the year of the October Revolution, a farmworker hoists a sheaf of wheat high above her head as if it were a dead weight she could finally throw off. During roughly the same years their American counterparts were seeking the vote. A section of the show is devoted to the National Woman’s Party, and the suffrage campaign has its own processional images, parades of women costumed as allegorical Virtues and carrying banners with tweet-short slogans. And at least some women were leading fully independent lives. Tina Modotti did. In 1913, still a teenager, she moved from Italy to San Francisco, and on to Mexico City. There, as a studio assistant and lover of Edward Weston, she learned photography and joined the Communist Party. Her Mexican still lifes, with cartridge belts and sickles piled on guitars, exploit the activist potential of visual beauty, though, disappointingly, the show offers no fresh insights into them, or into Modotti’s heavily mythologized life. Some of the most powerful pieces in the exhibition are those found in the NAACP’s series: “An Art Commentary on Lynching”. “The Lynching” by Julius Bloch depicts a dramatic oil-painted scene of a man hoisted up onto a beam with a large crowd surrounding him, imitating religious images of the crucifixion of Christ. Agitprop’s infamous use of banners can also be seen among this series in a 1936 photograph of a banner hanging out of a window of New York’s NAACP headquarters on 5th Avenue that simply reads, “A MAN WAS LYNCHED YESTERDAY”, forcing passersby to think about the horrific events that were still commonplace in the United States even decades after the abolishment of slavery. A more recent commentary on racism in can be found in Dread Scott’s series entitled “On the Impossibility of Freedom in a country Founded on Slavery and Genocide”, which shows the artist fighting against a high pressure fire hose, mirroring photographs of civil rights protesters of the 1960s. Other pieces included are footage from John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s “Bed Peace a wall wallpapered with Jenny Holzer’s “Inflammatory Essays” Others, like Mr. Scott, Martha Rosler, the Guerrilla Girls and the AIDS collective Gran Fury, have a kind of classic status locally, as do the Yes Men, whose fake Nov. 12, 2008, special edition of The New York Times, declaring the end of the war in Iraq, and the immediate return of troops, is here in all its brilliant counterfeit glory. Since 1989, the Sahmat Collective has been a steady force in the struggle against political and religious violence in India. Formed after the killing of the communist street-theater performer Safdar Hashmi, the group draws on art high and low to spread a message of sectarian harmony, including painting slogans on the auto-rickshaws that crowd South Asian cities. Agitprop! is a powerful exhibition that helps us to not only better understand history, it also challenges us to rethink the way we view our societies and the way that we view the world.

Info: Curators: Saisha Grayson, Catherine J. Morris, Stephanie Weissberg, and Jess Wilcox, Brooklyn Museum, 200 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, New York, Duration: 11/12/15-7/8/16, Days & Hours: Wed & Fri-Sun 11:00-18:00, Thu 11:00-22:00, www.brooklynmuseum.org