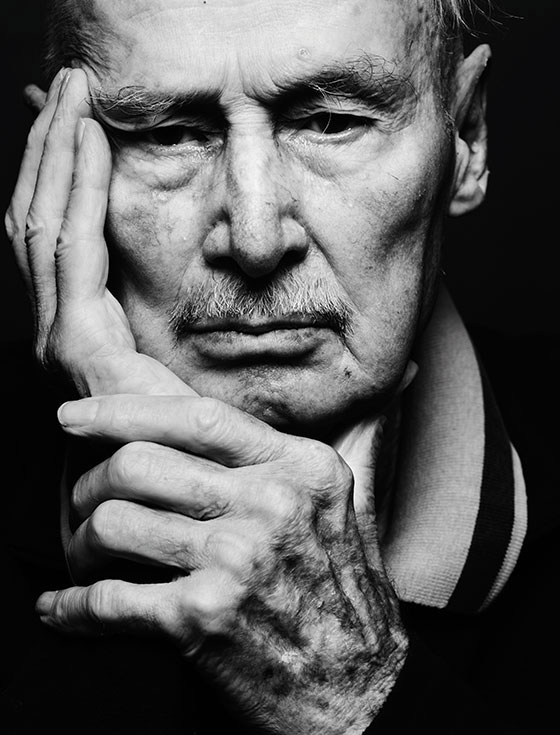

TRACES: Richard Artschwager

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Richard Artschwager (26/12/1923-9/2/2013), who forged a unique path in art from the early 1950s through the early 21st century, making the visual comprehension of space and the everyday objects that occupy it strangely unfamiliar. His work has been variously described as Pop art, as Minimal art and as conceptual art. But none of these classifications adequately define the aims of an artist who specialized in categorical confusion and worked to reveal the levels of deception involved in pictorial illusionism. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Richard Artschwager (26/12/1923-9/2/2013), who forged a unique path in art from the early 1950s through the early 21st century, making the visual comprehension of space and the everyday objects that occupy it strangely unfamiliar. His work has been variously described as Pop art, as Minimal art and as conceptual art. But none of these classifications adequately define the aims of an artist who specialized in categorical confusion and worked to reveal the levels of deception involved in pictorial illusionism. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

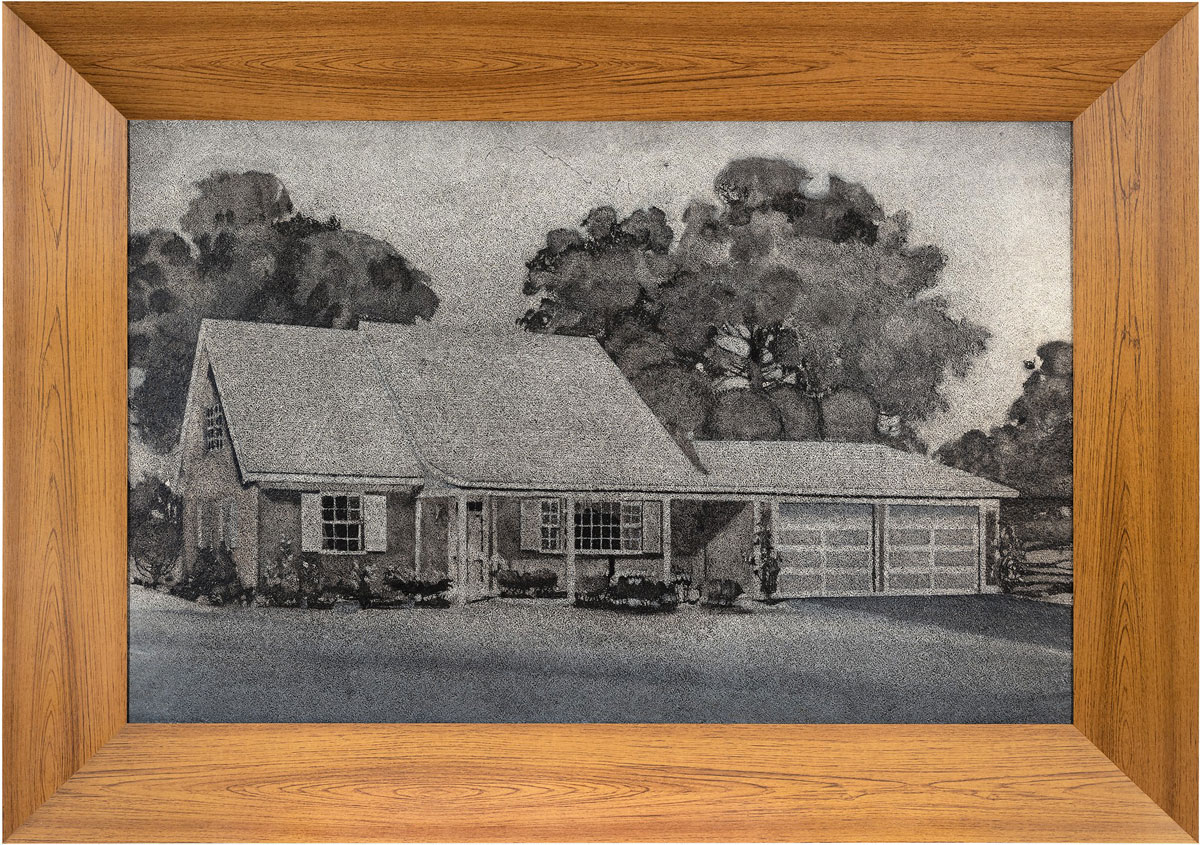

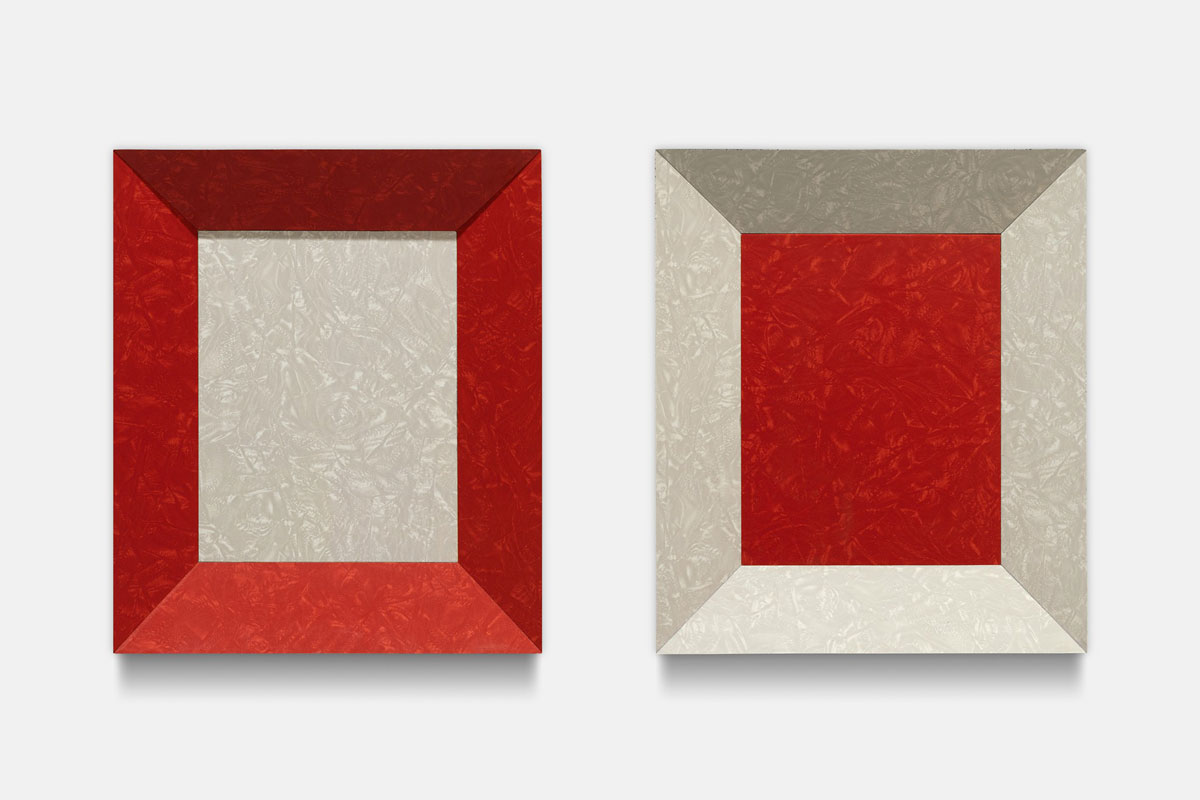

Born in Washington, D.C., Artschwager grew up in New Mexico, and studied chemistry and mathematics at Cornell University. Wounded while fighting in World War II, Artschwager worked as an administrator in Frankfort, and met his wife Elfriede Wejmelka on mission to Vienna. They returned to New York together, where she encouraged him to pursue his interest in his art. In 1949, he joined the studio of French cubist painter Amédée Ozenfant, but left the next year for a bank job due to financial reasons; his production throughout the 1950s was similarly interrupted, but, while employed, he was able to create a series of furniture. In the 1960s, Artschwager turned to sculpture, drawing attention to art’s illusionistic properties by painting over found wooden objects with artificial wood grains. He also began to paint naturalistic scenes of buildings, interiors, and figures in grisaille on celetox; these works grew increasingly abstract as Artschwager added illusionary elements that played with the viewer’s perception. During the 1960s Artschwager’s career gathered pace through a string of exhibitions. With his confidence at a new high, Artschwager sent slides and a covering letter to New York’s Leo Castelli Gallery, a renowned leader for showcasing new art. The gallery accepted him for a group exhibition where he took his place alongside the likes of Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg and Claes Oldenburg. The Castelli gave him his first solo exhibition in. The 1960s was a prolific period for Artschwager who found his artistic niche experimenting with a broad array of materials and styles. His art of the period straddled the space between art and function and the boundaries between realism and abstraction. He continued to experiment with Formica, making works with an appealingly glossy surface that typically made allusions to suburban domesticity. He was also drawn to Celotex, a roughly textured insulation board, onto which he began painting reproductions of found photographs depicting scenes from recent history. He discovered that painting on this surface could replicate the textural surface of poorly produced newsprint or television images. This effect echoed elements of Pop Art, but, in contrast to Pop Art, Artschwager’s imagery and motifs were more obscure, subtly toned and cerebral and leaned much closer to the language of Minimalism. While engaged in a teaching post at UC Davis in California, Artschwager became inspired by his fellow faculty staff who were exploring the workings of Minimalist languages. He recalled, “those guys set a good example – with William T. Wiley, Robert Arneson, Roy De Forest, Wayne Thiebaud and others”. Within his own practice he tried to refine his language into a more economical style leading him to discover his famous “blps” series. Artschwager adopted the trademark logo of the “blp” from the late 1960s until the end of his career, exploring how this odd black mark could alter the space in which it was placed. Indeed, he recreated his “blps” in a variety of materials to be installed inside gallery and museum spaces and also placed “blps” in the form of stencils and reliefs in museum grounds for visitors to happen upon or even to seek out.

Born in Washington, D.C., Artschwager grew up in New Mexico, and studied chemistry and mathematics at Cornell University. Wounded while fighting in World War II, Artschwager worked as an administrator in Frankfort, and met his wife Elfriede Wejmelka on mission to Vienna. They returned to New York together, where she encouraged him to pursue his interest in his art. In 1949, he joined the studio of French cubist painter Amédée Ozenfant, but left the next year for a bank job due to financial reasons; his production throughout the 1950s was similarly interrupted, but, while employed, he was able to create a series of furniture. In the 1960s, Artschwager turned to sculpture, drawing attention to art’s illusionistic properties by painting over found wooden objects with artificial wood grains. He also began to paint naturalistic scenes of buildings, interiors, and figures in grisaille on celetox; these works grew increasingly abstract as Artschwager added illusionary elements that played with the viewer’s perception. During the 1960s Artschwager’s career gathered pace through a string of exhibitions. With his confidence at a new high, Artschwager sent slides and a covering letter to New York’s Leo Castelli Gallery, a renowned leader for showcasing new art. The gallery accepted him for a group exhibition where he took his place alongside the likes of Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg and Claes Oldenburg. The Castelli gave him his first solo exhibition in. The 1960s was a prolific period for Artschwager who found his artistic niche experimenting with a broad array of materials and styles. His art of the period straddled the space between art and function and the boundaries between realism and abstraction. He continued to experiment with Formica, making works with an appealingly glossy surface that typically made allusions to suburban domesticity. He was also drawn to Celotex, a roughly textured insulation board, onto which he began painting reproductions of found photographs depicting scenes from recent history. He discovered that painting on this surface could replicate the textural surface of poorly produced newsprint or television images. This effect echoed elements of Pop Art, but, in contrast to Pop Art, Artschwager’s imagery and motifs were more obscure, subtly toned and cerebral and leaned much closer to the language of Minimalism. While engaged in a teaching post at UC Davis in California, Artschwager became inspired by his fellow faculty staff who were exploring the workings of Minimalist languages. He recalled, “those guys set a good example – with William T. Wiley, Robert Arneson, Roy De Forest, Wayne Thiebaud and others”. Within his own practice he tried to refine his language into a more economical style leading him to discover his famous “blps” series. Artschwager adopted the trademark logo of the “blp” from the late 1960s until the end of his career, exploring how this odd black mark could alter the space in which it was placed. Indeed, he recreated his “blps” in a variety of materials to be installed inside gallery and museum spaces and also placed “blps” in the form of stencils and reliefs in museum grounds for visitors to happen upon or even to seek out.

In 1971, Artschwager separated from Elfriede. A year later he re-married to the artist and writer, Catherine Kord. This shift in personal circumstances coincided with changes in his artistic practice as he moved into the realms of site-specific installation. His drawing and painting duly took on a greater architectural awareness, too, as he explored how he could create pictorial spaces through fragmented or abstracted symbols of domestic interiors. From these drawings emerged six principal objects – Door, Mirror, Table, Basket, Rug, Window – that became motifs in what he described as a “fugal exercise” in painting and drawing. With this his profile grew, he befriended and influenced a number of new artists including Ed Ruscha, Gerhard Richter and Malcolm Morley. Moving into the 1980s, he began working more and more on painted wood sculptures that mimicked the same artificial qualities of his earlier Formica works, but now with a much sharper sense of spatial and contextual awareness. From the late 1980s onwards Artschwager was hugely successful and busy enough to employ a team of studio assistants during a particularly prolific spell when he produced large-scale site-specific works. In 1989 Artschwager divorced Kord, later marrying Molly O’Gorman with whom he had two children. In 1991, while exhibiting his work with the Mary Boone Gallery, he met and fell in love again, this time with Ann Sebring, who was assisting at the gallery at the time. After divorcing O’Gornan in 1993, Artschwager married for a fourth and final time, the pair remaining a couple for the rest of his life. Known amongst his peers as a joker and trickster, the somewhat chaotic nature of his personal life was reflected in the eclectic nature of his creative ambitions. By the end of the century he declared that he had finally mastered both his personal and artistic goals. In this later period he looked back (as artists often do), revisiting the medium of painting on Celotex and exploring a range of figurative subjects. By the turn of the century Artschwager had commenced work on a series of portraits. In its 2013 career retrospective, Berlin’s Sprüth Magers Gallery described how the artist “rarely painted from real life” and usually preferred to construct his images “from memory [or to use] photographs and newspaper images enlarged to the size of easel paintings as the basis of his work”. In 2012 Artschwager produced a new series of mock-pianos, suggesting the essence of the object through various recognisable motifs. On first appearances the majestic aura of a grand piano is invested into this densely solid sculpture. But closer inspection reveals how Artschwager has deliberately created a tacky, cartoonish replica resembling a stage prop rather than an homage to the real thing. In these later pieces Artschwager consolidated many of the most important ideas of his career, uniting his uniquely irreverent humour with an interrogation into the boundaries between the real world and the art that represents it. He revisited his piano motif in a series of laminate sculptures in 2012. These pieces resembled different styles of grand and upright pianos, but rendered in an abstract manner that recalled the early twentieth century avant-garde. They proved to be his last significant pieces. Artschwager died in 9/2/2013 in Albany, New York after suffering a stroke. He was 89 years old.