TRACES: Ellen Gallagher

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Ellen Gallagher (16/12/1965- ), who builds multi-layered paintings that pivot between the natural world, mythology and history. Her painting process involves undoing and reforming trains of thought often over long periods of time and across linked bodies of works. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

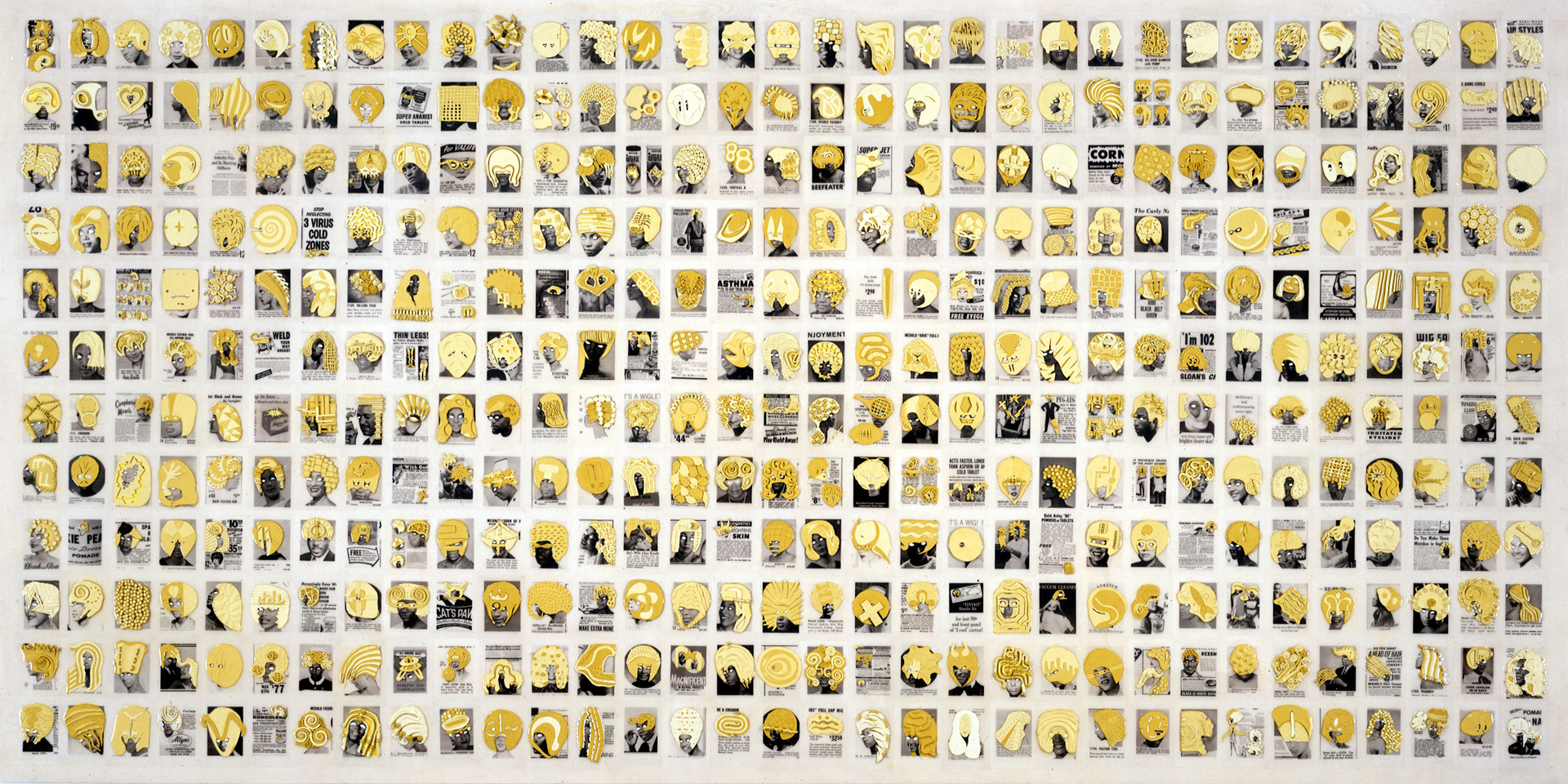

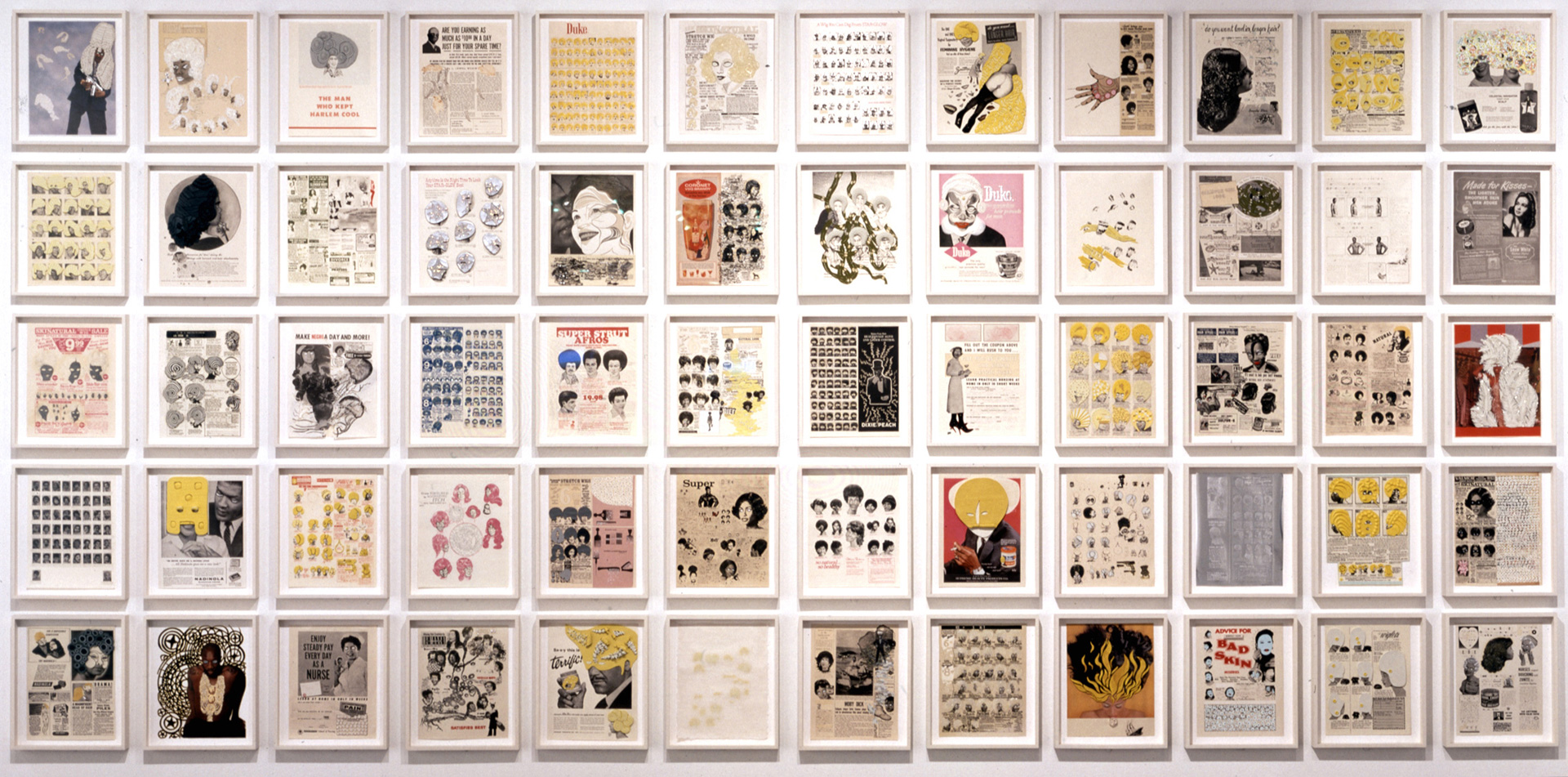

Born to an Irish-American mother, who raised her, and an African-American father, the artist was confronted at a young age by the idea of belonging and by the reality of latent racism. She studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (1992), then at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine (1993). Her work approaches racial identity, starting in the 1990’s, through a lens of cultural history. She is particularly interested in blackface minstrelsy, an American musical theater tradition that began in the 19th century, and consisted of white performers artificially blackening their faces with makeup. At the start of her career, Gallagher used the rules and effects of high modernist abstraction to create historically critical works of information and trauma. The formal effect is reminiscent of artists such as Agnes Martin or Ad Reinhardt, but instead of shapes and pencil lines that distort and shift, Gallagher’s forms are bow ties, mouths, and eyes. These shapes are taken from the iconography of minstrelsy, post–Civil War shows featuring white men in blackface that often had decidedly racist undercurrents. These changing, outmoded symbols of art and racism are called upon again to speak, not as harbingers of hate and repression but with messages full of historical weight and recovery. In “Untitled” (1996), Gallagher creates a richly metaphoric surface. Using the lined paper of elementary school handwriting practice, the artist establishes a loose grid across the canvas. On those sheets of paper, Gallagher obsessively repeats the stereotyped lips and eyes of minstrelsy, as if enacting the handwriting lessons of school. In such ways, Gallagher seems to suggest, historical stereotypes are promulgated through history—through the lessons of children and patterns of education. In 1998 Gallagher produced a small group of black monochromatic paintings as a direct response to the critical interpretations of her previous works. Starting again with squares of paper on canvas, she added more geometric shapes, creating a textured terrain that she built up with cut rubber. She further inscribed and collaged aleatory motifs from mid-century American race magazines and other sources, then painted the canvas in layers of black enamel. With this thick, reflective surface, Gallagher suggests that the psychosis of race relations is embedded in the history of Western abstraction. Gallagher was awarded the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Art in 2000 and began her ongoing “Watery Ecstatic” (2001- ) series the following year. In Watery Ecstatic” she invents complex biomorphic forms that she relates to the mythical Drexciya, an undersea kingdom populated by the women and children who were the tragic casualties of the transatlantic slave trade. Cutting into thick paper in her own version of scrimshaw—the practice of carving whale bones—Gallagher invests the afterlives of the Middle Passage with a sense of material control, her intense focus giving rise to new peripheries. Drexciya is featured again in Gallagher’s film installation “Murmur” (2003–04), made in collaboration with Dutch artist Edgar Cleijne. Combining celluloid film with computer animation, Gallagher and Cleijne developed an aesthetic that emerges from the intersection of archival sources, fiction, and memory. In “Pomp-Bang” (2003), she collected images drawn from magazines marketed to African-American women (lauding the merits of skin-lightening creams or hair-relaxing products) imposing a certain ideal of beauty, and covered them in abstractly-shaped yellow plasticine wigs, transforming them from figures of “beauty” to monstrous beings. “eXelento” (2004), is a monumental modernist grid that breaks into isolated magazine pages, showing altered hair product ads from vintage Ebony, Black Digest, and Our World magazines. The women, taking on otherworldly guises with thick, Plasticine hairstyles, are prominently featured. The structure of the grid is animated through these historical symbols, resulting in a deconstruction of the double oppression of African American women: first by a paternalistic society and second by ongoing racial friction. At the same time, however, Gallagher praises the creativity and innovations of the hairstyles, affirming the beautiful creations as one part of a complex social identity. The surface is both critical and joyful, intensely detailed and bursting with information. In 2006 Gallagher made “Bird in Hand”, a large-scale, mixed-media canvas depicting a black pirate or sailor holding a parrot, with amorphic swirls around his head transforming into multicolored kelp-like shapes. Inspired by both Captain Ahab from Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick and the Cape Verde archipelago, the protagonist in the painting, “Pegleg,” is a recurring character in Gallagher’s art, combining her long-standing interest in underwater forms with her critical engagement with the history of Cape Verde, where her father’s parents were born. Gallaghers series of watercolors, “Coral Cities” (2007), are the epitome of this skill. Utilizing research she had undertaken in 1986 aboard an oceanographic research vessel, Gallagher makes tenuous yet remarkable links between the migratory patterns of pteropods – microscopic wing-footed snails, and the slave trade. The watercolours fixate on ‘Drexciya’ the mythic offspring of black African women who drowned during the Middle Passage; the marine flora and coral adorning the crowns of women, offering them an imaginary respite and delicate immortalization. From 2008 to 2012 Gallagher worked on “Morphia”, a series of double-sided drawings displayed in custom glass and metal cabinets, in which representations of transformed artifacts merge with marine imagery to create transparent palimpsests resembling stroma or organic matter. As they mutate and congeal, microbial patterns seem to convey a certain euphoria, a narcotic state suggested by the series title. In 2010, for the Whitney Biennial, Gallagher and Cleijne created “Better Dimension”, an installation in which the outer walls of a large room were silkscreened with writings by Afrofuturist pioneer Sun Ra, the Martian canals of Percival Lowell, as well as the long legs of singer and bassist Shingai Shoniwa. Inside the room, projections showed syncopated sequences of painted glass slides and John F. Kennedy’s head rotating above a black vinyl LP. Three years later, in 2013, AxME opened at the Tate Modern, London and traveled to the Sara Hildén Art Museum, Finland, and Haus der Kunst, Munich; Don’t Axe Me opened at the New Museum, New York, that same year. In the film installation “Highway Gothic” (2017), Gallagher collaborated with Cleijne again, examining the impact that Interstate 10 is having on people and nature in the Southern United States. Originating at Prospect.4 in New Orleans, Highway Gothic has continued to develop and was included in solo exhibitions of Gallagher’s work at Bonniers Konsthall, Stockholm, and the Power Plant, Toronto, in 2018.

Born to an Irish-American mother, who raised her, and an African-American father, the artist was confronted at a young age by the idea of belonging and by the reality of latent racism. She studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (1992), then at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine (1993). Her work approaches racial identity, starting in the 1990’s, through a lens of cultural history. She is particularly interested in blackface minstrelsy, an American musical theater tradition that began in the 19th century, and consisted of white performers artificially blackening their faces with makeup. At the start of her career, Gallagher used the rules and effects of high modernist abstraction to create historically critical works of information and trauma. The formal effect is reminiscent of artists such as Agnes Martin or Ad Reinhardt, but instead of shapes and pencil lines that distort and shift, Gallagher’s forms are bow ties, mouths, and eyes. These shapes are taken from the iconography of minstrelsy, post–Civil War shows featuring white men in blackface that often had decidedly racist undercurrents. These changing, outmoded symbols of art and racism are called upon again to speak, not as harbingers of hate and repression but with messages full of historical weight and recovery. In “Untitled” (1996), Gallagher creates a richly metaphoric surface. Using the lined paper of elementary school handwriting practice, the artist establishes a loose grid across the canvas. On those sheets of paper, Gallagher obsessively repeats the stereotyped lips and eyes of minstrelsy, as if enacting the handwriting lessons of school. In such ways, Gallagher seems to suggest, historical stereotypes are promulgated through history—through the lessons of children and patterns of education. In 1998 Gallagher produced a small group of black monochromatic paintings as a direct response to the critical interpretations of her previous works. Starting again with squares of paper on canvas, she added more geometric shapes, creating a textured terrain that she built up with cut rubber. She further inscribed and collaged aleatory motifs from mid-century American race magazines and other sources, then painted the canvas in layers of black enamel. With this thick, reflective surface, Gallagher suggests that the psychosis of race relations is embedded in the history of Western abstraction. Gallagher was awarded the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Art in 2000 and began her ongoing “Watery Ecstatic” (2001- ) series the following year. In Watery Ecstatic” she invents complex biomorphic forms that she relates to the mythical Drexciya, an undersea kingdom populated by the women and children who were the tragic casualties of the transatlantic slave trade. Cutting into thick paper in her own version of scrimshaw—the practice of carving whale bones—Gallagher invests the afterlives of the Middle Passage with a sense of material control, her intense focus giving rise to new peripheries. Drexciya is featured again in Gallagher’s film installation “Murmur” (2003–04), made in collaboration with Dutch artist Edgar Cleijne. Combining celluloid film with computer animation, Gallagher and Cleijne developed an aesthetic that emerges from the intersection of archival sources, fiction, and memory. In “Pomp-Bang” (2003), she collected images drawn from magazines marketed to African-American women (lauding the merits of skin-lightening creams or hair-relaxing products) imposing a certain ideal of beauty, and covered them in abstractly-shaped yellow plasticine wigs, transforming them from figures of “beauty” to monstrous beings. “eXelento” (2004), is a monumental modernist grid that breaks into isolated magazine pages, showing altered hair product ads from vintage Ebony, Black Digest, and Our World magazines. The women, taking on otherworldly guises with thick, Plasticine hairstyles, are prominently featured. The structure of the grid is animated through these historical symbols, resulting in a deconstruction of the double oppression of African American women: first by a paternalistic society and second by ongoing racial friction. At the same time, however, Gallagher praises the creativity and innovations of the hairstyles, affirming the beautiful creations as one part of a complex social identity. The surface is both critical and joyful, intensely detailed and bursting with information. In 2006 Gallagher made “Bird in Hand”, a large-scale, mixed-media canvas depicting a black pirate or sailor holding a parrot, with amorphic swirls around his head transforming into multicolored kelp-like shapes. Inspired by both Captain Ahab from Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick and the Cape Verde archipelago, the protagonist in the painting, “Pegleg,” is a recurring character in Gallagher’s art, combining her long-standing interest in underwater forms with her critical engagement with the history of Cape Verde, where her father’s parents were born. Gallaghers series of watercolors, “Coral Cities” (2007), are the epitome of this skill. Utilizing research she had undertaken in 1986 aboard an oceanographic research vessel, Gallagher makes tenuous yet remarkable links between the migratory patterns of pteropods – microscopic wing-footed snails, and the slave trade. The watercolours fixate on ‘Drexciya’ the mythic offspring of black African women who drowned during the Middle Passage; the marine flora and coral adorning the crowns of women, offering them an imaginary respite and delicate immortalization. From 2008 to 2012 Gallagher worked on “Morphia”, a series of double-sided drawings displayed in custom glass and metal cabinets, in which representations of transformed artifacts merge with marine imagery to create transparent palimpsests resembling stroma or organic matter. As they mutate and congeal, microbial patterns seem to convey a certain euphoria, a narcotic state suggested by the series title. In 2010, for the Whitney Biennial, Gallagher and Cleijne created “Better Dimension”, an installation in which the outer walls of a large room were silkscreened with writings by Afrofuturist pioneer Sun Ra, the Martian canals of Percival Lowell, as well as the long legs of singer and bassist Shingai Shoniwa. Inside the room, projections showed syncopated sequences of painted glass slides and John F. Kennedy’s head rotating above a black vinyl LP. Three years later, in 2013, AxME opened at the Tate Modern, London and traveled to the Sara Hildén Art Museum, Finland, and Haus der Kunst, Munich; Don’t Axe Me opened at the New Museum, New York, that same year. In the film installation “Highway Gothic” (2017), Gallagher collaborated with Cleijne again, examining the impact that Interstate 10 is having on people and nature in the Southern United States. Originating at Prospect.4 in New Orleans, Highway Gothic has continued to develop and was included in solo exhibitions of Gallagher’s work at Bonniers Konsthall, Stockholm, and the Power Plant, Toronto, in 2018.