PRESENTATION: Ruth Asawa-Citizen of the Universe

The hanging display of Ruth Asawa’s sculptures and craft-like appearance led to only a limited number of people accepting Ruth Asawa’s art. This changed after her work was on the cover of Arts & Architecture in 1952 and Vogue in 1953. In 1954, Ruth Asawa had her first exhibition in New York and one year later her works were bought by the Rockefellers and Philip Johnson. Despite the fact that all of her works are unique, many of them can be assigned to a group containing similar expressions of the artist’s ideas and influences during a specific time.

The hanging display of Ruth Asawa’s sculptures and craft-like appearance led to only a limited number of people accepting Ruth Asawa’s art. This changed after her work was on the cover of Arts & Architecture in 1952 and Vogue in 1953. In 1954, Ruth Asawa had her first exhibition in New York and one year later her works were bought by the Rockefellers and Philip Johnson. Despite the fact that all of her works are unique, many of them can be assigned to a group containing similar expressions of the artist’s ideas and influences during a specific time.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Stavanger Art Museum Archive

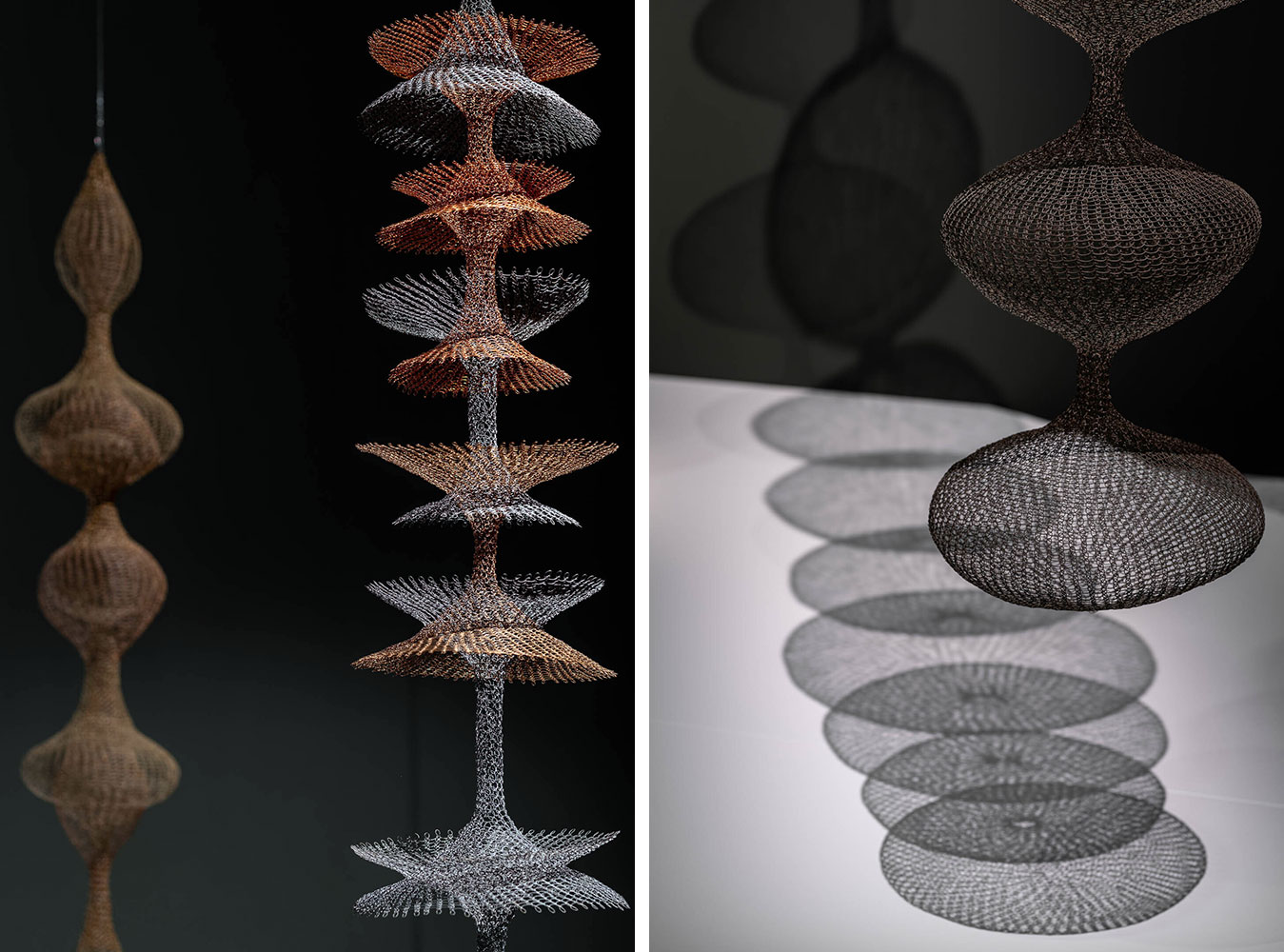

The exhibition “Citizen of the Universe” takes a unique look at the visionary artist, educator and activist Ruth Asawa and features her signature hanging sculptures in looped and tied wire, and celebrates her holistic integration of art, education and community engagement through displaying prints, drawings, letters and photographs. For Ruth Asawa, teaching art and learning were vital activities for dynamically engaging with life. Her sculpture work can be divided in four categories: Looped-Wire Sculpture: In 1954, Asawa was asked to explain her work for her first show at the Peridot Gallery in New York. What set her work apart from others making sculpture then was their lightness and transparency, as well as their movement since they were suspended from the ceiling. She wrote, “A woven mesh not unlike medieval mail. A continuous piece of wire, forms envelop inner forms, yet all forms are visible (transparent). The shadow will reveal an exact image of the object.” It was only much later in life that she realized that she had made the same forms as a young child on her parents’ farm. Sitting on the back of a horse-drawn leveler, which scraped the soil so that irrigation water could reach the end of the rows, she dragged her toes in the fine soil as the horses walked to make the playful and complex biomorphic outlines of her looped wire sculptures. Tied-Wire Sculpture: Asawa often describes these tied-wired sculptures using terms such as “tree” and “branching form.” She began with a center stem of 200 to 1,000 wires, which she then divided into branches using nature as her model. As she continued working in this form, she moved into more abstract forms using geometric centers of four, five, six, and seven points. If you look at these sculptures, you can see how the number of points in the center defines the forms that the branches take. As with her other work, these tied wire forms gave her the freedom to explore how “the relation between outside and inside was interdependent, integral”. Electroplated Sculpture: Beginning in the mid-1950s, Asawa sought advice on how best to clean her looped-wire sculptures from industrial plating companies in San Francisco. The brass, iron, and copper were beginning to tarnish and oxidize. A couple of businesses dismissed her request to clean sculptures as not worth their effort. But she finally found C&M Plating Works, where Carl and Mac “took pity on me and were willing to try new things.” They helped her experiment with cleaning methods and patinas. On a trip to the platers in the early 1960s, Asawa noticed some crusty copper bars in the plating tank, the byproduct of a process that smoothed the chrome for car bumpers. She admired their gritty texture and green patina. She asked Mac to help her figure out how to get the same texture and color on her tied wire sculptures. Through trial and error, they reversed the electroplating process. After she formed the sculpture in copper wire, it remained in a chemical tank for months, where it grew layers of rough, green and colorful textured skin similar to coral or bark. Cast Sculpture: Asawa began experimenting with cast forms in the mid 1960s. For her first public commission in San Francisco, the Andrea mermaid fountain at Ghirardelli Square, she had to design the mermaid’s tail. Her solution was to first loop it in wire, then dip it in wax, and then cast it in bronze. She enjoyed working with the foundrymen at the San Francisco Art Foundry, and she was captivated by how she could take an idea from one material, add to it with wax, have it invested or made into a mold, and then see it transformed into bronze. She did this with wire, paper, baker’s clay, even persimmon stems. Her cast sculptures reaffirmed what she learned from her teacher Josef Albers at Black Mountain College, “The artist must discover the uniqueness and integrity of the material”.

Ruth Asawa was born to Japanese parents who worked as farm labourers in rural Norwalk, California. In 1942, she and her family were forced into US concentration camps where people of Japanese ancestry were forcibly interned during World War II. But in her time there she met interned professional artists and Disney animators, who, along with other teachers, taught Asawa to draw directly from nature. She continued with this observational drawing practice throughout her life. She was released from the internment camp to train as an art teacher. Asawa attended Black Mountain College from 1946 to 1949. She excelled as an outstanding young artist with notable emotional maturity, and was also adept at farming and community living. At the college she was taught by international artists and progressive tutors who believed in expertise, collaboration, and individually learning from experience. Asawa said the teachers at Black Mountain College: “profoundly influenced my outlook on the value of life and the true nature of freedom”. From Asawa’s recollections, artists Anni and Josef Albers had a notable influence on her, along with inventor, environmentalist and architect R. Buckminster Fuller. Anni Albers, along with others, role modelled a modern feminism that was entirely new to Asawa, showing the importance of women having their own creative practice and social equality. Josef Albers was one of the most influential art educators of the 20th century, and Asawa’s mentor. His classes centred on making works from inexpensive materials in response to questions about visual perception, practically demonstrating with the students how colors interact, or how a three-dimensional form could be made from paper, or a line of wire. His teaching drew inspiration from Taoism and Zen Buddhism, which reconnected Asawa to her parents’ beliefs, but in her own fresh way. In the summer of 1948, meeting R. Buckminster Fuller was galvanising for Asawa. Fuller argued for the invention of structures through learning from nature. He promoted living holistically as citizens of one planet, who are part of the universe, not nations at war. Through his lectures Asawa’s relationship with student architect Albert Lanier blossomed, and the couple decided to wed. In 1949 Asawa joined Lanier in San Francisco where interracial marriage had recently been legalised. Fuller designed their wedding ring – three conjoined ‘A’ letters – to represent the synergistic energy of the universe being manifest in their union. Asawa discovered a whole new way of being in the world through art. She became determined to have a thriving future as an artist and mother. In preparation, Asawa freed herself from feeling victimised and traumatised by the racial prejudices of her time through conscientious personal development. In her final months of study at Black Mountain College, she cast off the national and racial labels that had caused her such pain, privately rejecting the labels ‘American’ and ‘Japanese’ and instead choosing to identify as “a citizen of the universe”. Asawa’s growing sense of true inner freedom motivated her lifelong artistic and civic contribution to society.

From the late 1940s to the turn of the 21st century, Asawa created her distinctive hanging sculptures from lines of wire that she looped and tied into elegant new forms. Asawa’s sculptures are an exploration of structures within nature, and are born out of her close observations of organic life. Her concepts are informed by the artistic, scientific, and cultural insights – including environmentalism and Buddhism, that she learned at Black Mountain College. In Asawa’s words, “the shadow cast by the sculpture reveals as much as the sculpture itself. … Many of the forms are inspired by plant growth, bone structures and patterns seen in water and oil, soap bubbles and smoke”. Made by hand, each of Asawa’s sculptures is a voluminous form ingeniously created with minimal materials. Her works aesthetically combine tangible, visible lines of wire with the spaces between the lines so that they appear as one unified whole. Asawa had considerable success as a young artist with exhibitions in New York, San Francisco and Oakland during the 1950s. She also briefly ventured into commercial design with fabric and wallpaper designs based on pattern work, including her recognisable BMC laundry stamp print, which she playfully made while at college. From the late 1960s Asawa prioritised civic engagement as an artist, whilst continuing her own solo practice and caring for her and Lanier’s six children. She developed a form of social art practice working with communities, and was active in lobbying for policy changes at a local and governmental level. Creatively she worked on site-specific public sculptures made with and for local communities. In 1968, Asawa and Sally Woodridge set up the Alvarado School Arts Workshops, which reached over 50 schools in ten years. Asawa served on multiple committees championing artists as active citizens, including the Role of the Arts committee for President Carter’s Commission on Mental Health. In 1982, the date of 12 February was declared the annual Ruth Asawa Day. That same year, against the odds, she successfully founded a state art high school which, in honor of her contribution to the city, was renamed the Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts in 2010. She was formidable as an advocate for the importance of creative activity in community life. Asawa’s sculptures and drawings asserted her individual sense of inner freedom, which in turn motivated her integration of art, family life and decades of civic engagement in San Francisco and beyond.

Photo: Ruth Asawa, Citizen of the Universe, Exhibition view Stavanger Art Museum, Stavanger, 2022-2023, Courtesy Stavanger Art Museum

Info: Curators: Vibece Salthe and Emma Ridgway, Stavanger Art Museum, Henrik Ibsens gate 55, Stavanger, Norway, Duration: 1/10/2022-22/1/2023, Days & Hours: Tue-Wed & Fri 11:00-15:00, Thu 11:00-19:00, Sat-Sun 11:00-16:00, https://stavangerkunstmuseum.no/