PRESENTATION: Cy Twombly

Cy Twombly ranks among the most prominent US painters to emerge in the 1950s, a period of radical experimentation in American and European art. Combining gestural strokes of paint, broad areas of empty space, and words scribbled in a nearly illegible hand, Twombly’s work can be enigmatic, even perplexing. Making sense of it requires an appreciation of his attitudes toward history, place, and cultural memory.

Cy Twombly ranks among the most prominent US painters to emerge in the 1950s, a period of radical experimentation in American and European art. Combining gestural strokes of paint, broad areas of empty space, and words scribbled in a nearly illegible hand, Twombly’s work can be enigmatic, even perplexing. Making sense of it requires an appreciation of his attitudes toward history, place, and cultural memory.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: J. Paul Getty Museum & Gagosian

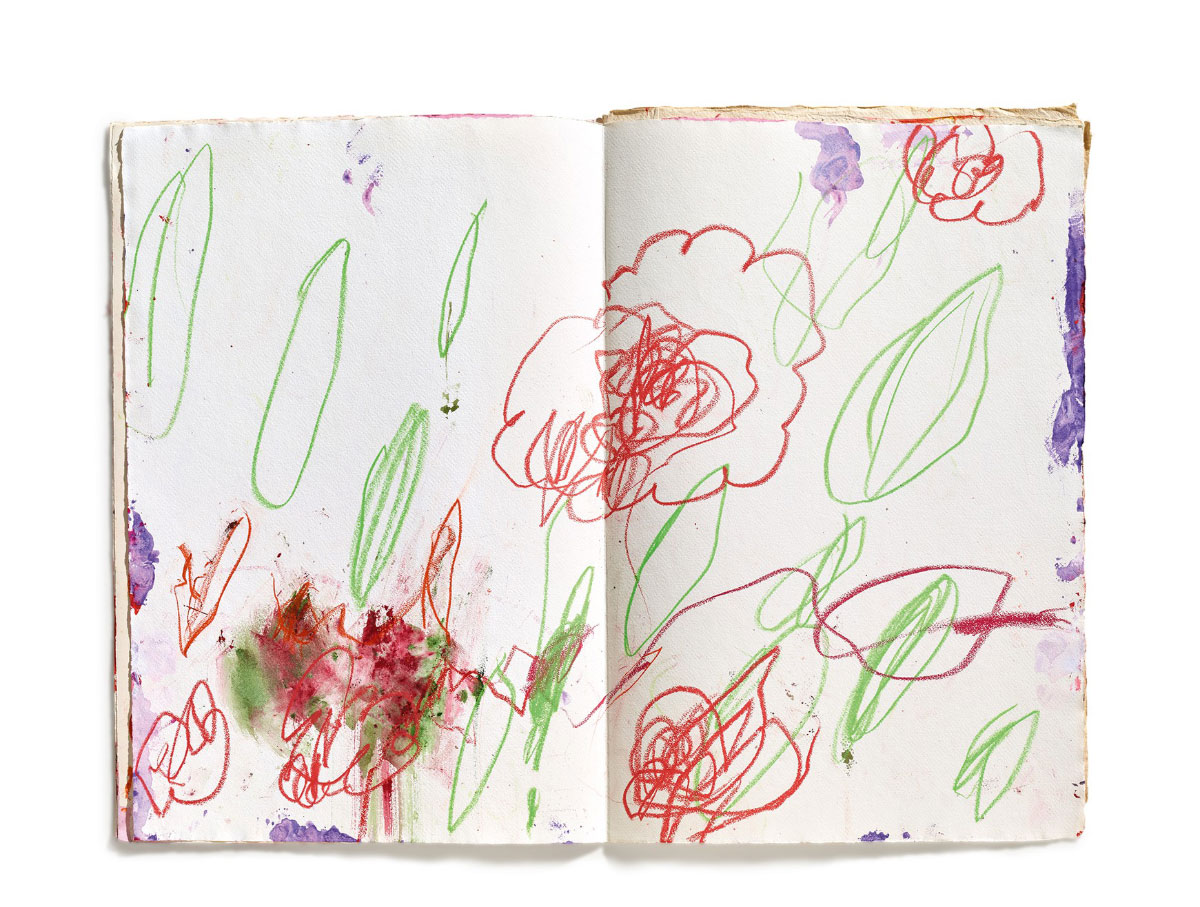

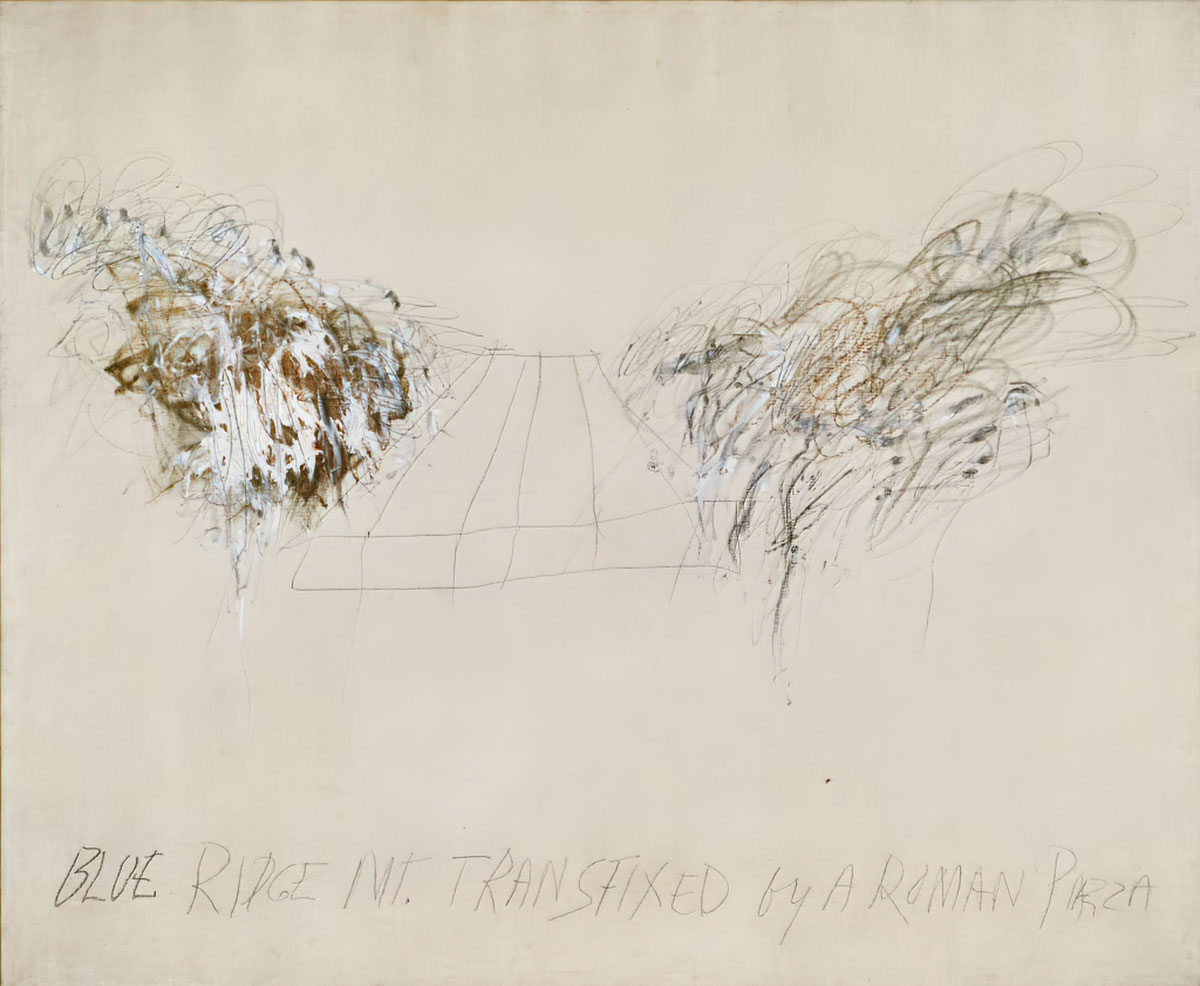

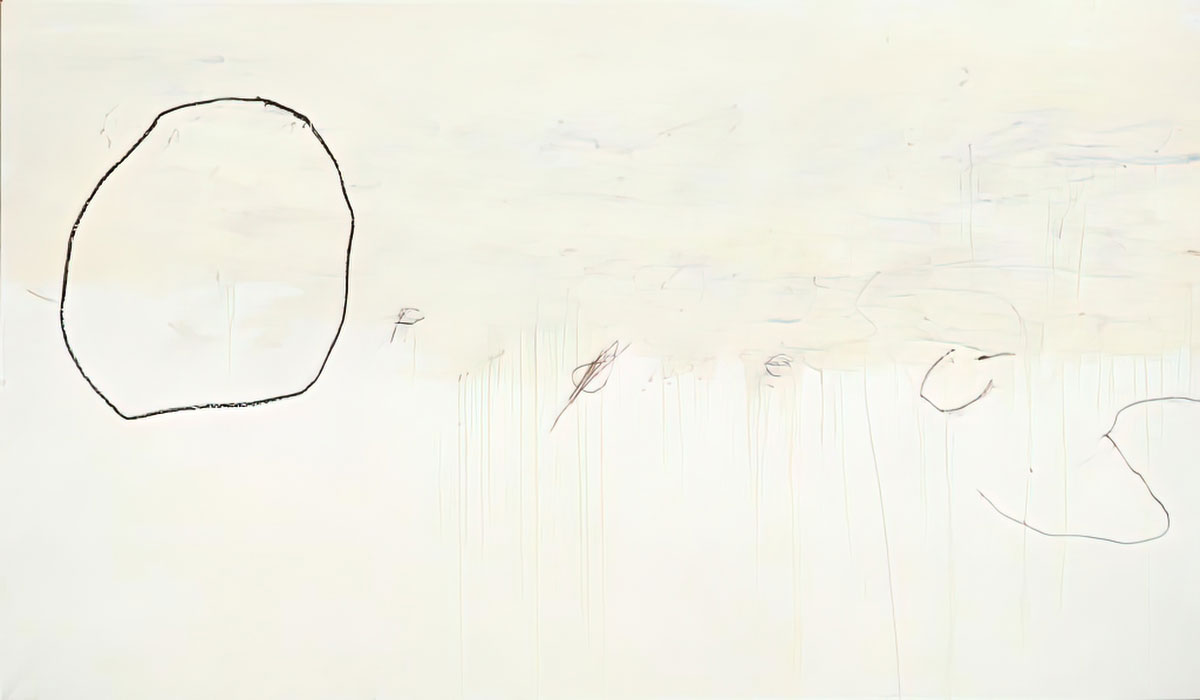

Two exhibitions with works by Cy Twombly are on show in Los Angeles, an exhibition with paintings, sculptures, and works on paper at Gagosian Gallery and “Making Past Present” at J. Paul Getty Museum, that explores Twombly’s engagement with the art, culture, and history of the ancient Mediterranean. Working in Gaeta, Italy, and Lexington, Virginia, Twombly returned to painting at a large scale in the 2000s. The shift followed his 1994 retrospective at the MoMA, New York, and the critical success of “Lepanto”, a suite of twelve paintings first shown at the 49th Biennale di Venezia in 2001. In these works, he adopted a new approach to color with palettes of lush, saturated hues. Slender lines and loops of paint balance expressive dynamism and elegance, while denser strokes evoke the petals of peonies and chrysanthemums. The paintings are imbued with the uninhibited spirit of Bacchanalia and the vivacity of fresh blossoms; at once vital and elegiac, they meditate on poetry, history, and myth. In Gagosian Gallery, one highlight is a set of six panels composed with verdant greens and luminous white, “Untitled I–VI” (Green Painting) (2002–03), which was presented only once before as part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2016 exhibition “Unfinished: Thoughts Made Visible”. Also included are Twombly’s works on paper, which blur the distinctions between painting, drawing, and writing, and his sculptures, which extend his concerns with geometry, gesture, and materiality into three dimensions. Assembled from plaster, wood, and scraps found in his studio, these objects suggest fragments of the monumental architectonic and sculptural forms of ancient Egypt, Rome, and Greece. Twombly often painted the sculptures white or cast them in bronze, unifying their disparate forms while retaining the tactility of their surfaces.

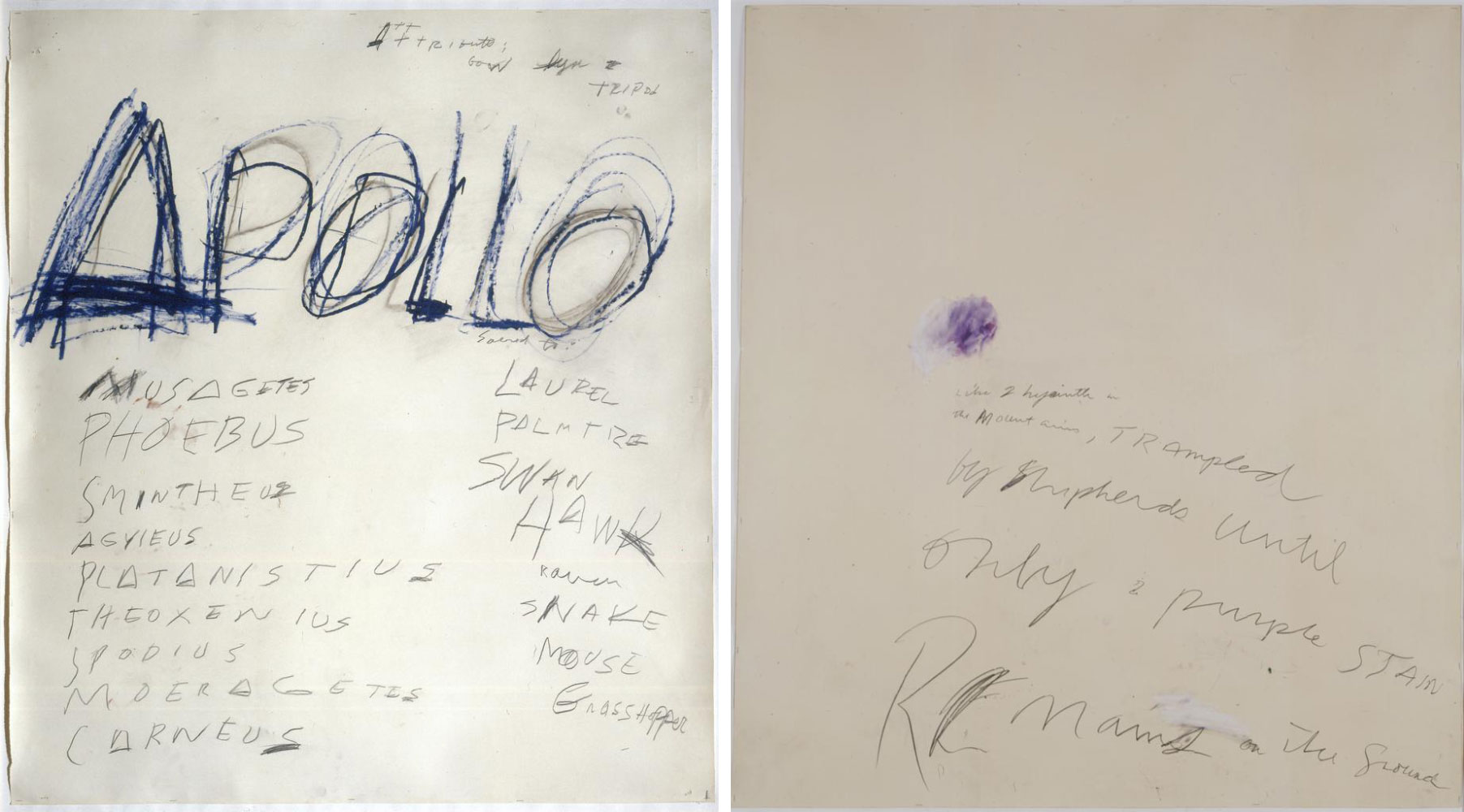

The exhibition “Making Past Present” explores Twombly’s art through the lens of ancient Greek and Roman culture, a consistent source of inspiration throughout his career. Twombly avoided centers of modern art like New York, moving to Italy in 1959. There he engaged creatively with the enduring legacy of antiquity, infusing his work with provocative allusions to mythology, poetry, and archaeology. By exploring the classical past, Twombly followed a long tradition in American and European art. Travel inspired Twombly’s art, but so did his domestic environments, which were themselves often historical spaces where he lived casually alongside his own work and the antiquities that he passionately collected. His paintings were sometimes described as “rooms,” which viewers could metaphorically enter, while the actual rooms he inhabited call to mind his paintings: whitewashed, spare yet dynamic, replete with references to worlds old and new. In 1966 the photographer Horst P. Horst portrayed Twombly, as well as his wife Tatiana Franchetti and son Alessandro, in their Rome apartment for a profile in Vogue magazine, titled “Roman Classic Surprise”. The photos highlighted the artist’s habit of displaying ancient sculptures together with antique furniture, his own art, and the works of his contemporaries, including Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and Claes Oldenburg. According to the article, “The apartment is indescribable in terms of decoration, if only because its contents are involved in a continuous process of removal and replacement.” Annabelle d’Huart, who later photographed Twombly’s homes in Rome and Bassano, noted that the “entire environment was exactly like a Twombly painting.” Words—names, phrases, excerpts of poetry— form a primary element of Twombly’s work. He once said, “I like poets because I can find a condensed phrase . . . the essence of something.” The graphic notations that abound in his paintings and drawings invite viewers to read aloud and listen as well as to look, making engagement with Twombly’s art a multisensory experience.

In 1951 Twombly met the American modernist poet Charles Olson, who practiced breath-based poetics and sought spontaneity in his writing. For this effect he took the syllable, not the word, as the unit of creation, and he found “breath” in the spacing and page layouts and in the breaking up of a sensible flow of narrative. Just as Olson’s poetry has a strong visual aspect incorporating spaces (silences) and disjunctions, so too does Twombly’s art employ white paint, fragmentation, gaps, sparse surfaces, and erasures. Throughout his career Twombly was drawn to Aphrodite (Venus to the Romans), the goddess of desire and love. His preoccupation came in part from his dedicated readings of translations from the early Greek poets, especially Sappho, who often evoked the deity as both a muse and a tyrant. Twombly broke with the long tradition of representing Aphrodite as the embodiment of ideal female beauty. He preferred to reference her through words—her various names as well as the places where she was worshipped—or through abstract gestures and shapes like trapezoids and rectangles that were perhaps stand-ins for ancient sculptures. While Twombly’s scrawls and layers of mark making and erasure can seem enigmatic, his works devoted to Aphrodite/Venus reveal a visceral sensuality, luring the viewer into his vision of desire, passion, and the violence that forever accompanies the goddess. The works Twombly dedicated to the war god Mars are thematic counterparts to those he devoted to Venus. Considered together, they raise fundamental questions about the relation between sex and violence, femininity and masculinity, creation and destruction. The selection displayed here refers to murderous power struggles, legendary warriors, and famous battles in ancient history and myth—and resonates with the ancient armor that the artist collected. Twombly’s touchstones were classics like Homer’s epic the Iliad, but he subversively reimagined them, translating their violence through his chaotic, libidinal mark making; the field of painting itself becomes a figurative battlefield. While engaging with the distant past, Twombly’s art pointedly addressed his historical moment, which was marred by political assassinations and the Vietnam War.

Photo: Cy Twombly, Untitled, 2002 Acrylic, wax crayon, and pencil on handmade paper, in unbound handmade book, 16 pages, each page (approximately): 22 ½ × 15 ¼ inches (56.9 × 38.7 cm, © Cy Twombly Foundation. Photo: Peter Schälchli, Courtesy Gagosian

Info: J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center, 1200 Getty Center Dr, Los Angeles, CA, USA, Duration: 2/8-30/10/2022, Days & Hours: Tue-Fri & Sun 10:00-17:30, Sat 10:00-20:00, www.getty.edu/ & Gagosian Gallery, 456 North Camden Drive, Beverly Hills, CA, USA, Duration: 15/9-17/12/2022, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-17:30, https://gagosian.com/

Right: Cy Twombly, Untitled (to Sappho), 1976, Oil paint, wax crayon, and graphite on paper, Private Collection, © Cy Twombly Foundation. Photo: Mimmo Capone

Right: Cy Twombly, Thermopylae, 1992, Bronze, The Menil Collection, Houston. Gift of the artist, © Menil Foundation, Inc. Photo: Hickey-Robertson, Houston

Right: Cy Twombly, Untitled, 2007 Acrylic and pencil on wood panel, in artist’s frame, 104 ¾ × 79 × 2 ½ inches (266.1 × 200.7 × 6.3 cm), © Cy Twombly Foundation, Courtesy Gagosian