PHOTO: Wolfgang Tillmans-To Look Without Fear

Wolfgang Tillmans’s approach to making pictures is grounded in the possibility of forging human connections and in the idea of togetherness, and his work reflects not only his irrepressible curiosity but also a deep care for his subjects. He considers his role to be, among other things, that of an “amplifier” of ideas and of social awareness.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: MoMA Archive

Wolfgang Tillmans in, “To look without fear”, his first museum survey in New York” presents groupings of approximately 350 of hi photographs, videos, and multimedia installations will be displayed according to a loose chronology, the exhibition highlights how Tillmans’s profoundly inventive, philosophical, and creative approach is both informed by and designed to highlight the poetic possibilities and social and political causes for which he has been an advocate throughout his career. The works that are installed at the entrance to the exhibition exemplify Tillmans’s engagement with new forms of technology, which is traceable to his childhood passion for astronomy. It was through his early trials with the telescope, and later with the photocopier and video camera, that he ultimately arrived at his photographic practice. “Victoria Park” (2007), depicting two friends lounging in a park in East London, reflects his long-standing engagement with the laser photocopier, which he first happened upon as a teenager in a local print shop in 1986. Often enlarging images up to 400 percent, Tillmans aspired to expand the limits of photographic materials and techniques, an ambition that aligned with his near-contemporaneous experiments with electronic music. In the 2017 video “untitled (leg)”, a single bare leg rotates slowly in rhythm, recalling 19th-century pre-cinematic motion studies, while its vertical aspect ratio evokes a 21st century-format: the smartphone screen. In the exhibition’s first gallery, Tillmans’s early photocopies are installed alongside images that brought him to prominence as a chronicler of youth subculture and nightlife, including “Lutz & Alex sitting in the tree” (1992) and “Chemistry Squares” (1992), which were both published in the British alternative magazine i-D in the early 1990s. The persistent presence of magazines in his exhibitions is indicative of how Tillmans harnesses the capacity of his pictures to amplify ideas when they are distributed across media platforms. The second gallery includes early photographs that foreground Tillmans’s abiding interest in music and performance. His portrait, made for Interview magazine in 1995, of the legendary DJ Joanne Joseph is installed near “wall of speakers” (1992), made on a trip to Kingston, Jamaica, where Tillmans photographed the local ragga music scene. This photograph captures an outdoor festival’s precariously stacked sound system, depicting the structure as both a sculptural object and a means of experimentation capable of producing thunderous bass sounds. The following gallery includes works that speak to Tillmans’s subversion of traditional art-historical subjects and genres. In the photographs he calls “Faltenwurf” (German for “drapery”), clothes hang drying on radiators, are crumpled into balls, or lie in heaps, alluding to drawn and painted studies of fabric. Beginning in the late 1990s, Tillmans became increasingly invested in the possibilities afforded by darkroom abstraction, experimenting with new techniques, such as applying colored tints and using flashlights to manipulate a negative while it developed. In his monumental “I don’t want to get over you” (2000), a title inspired by the lyrics of a song by the Magnetic Fields, gestural green streaks and dark, thread-like lines fuse with the image of a vast, barren-looking, otherworldly landscape. Tillmans’s video works brings together movement, electronic music, ambient sound, technology, and quotidian imagery. The fourth gallery features two such video works. “Lights (Body)” (2000–02) focuses on the flashing lights in a busy nightclub, revealing the specks of dust rising off the ravers’ clothes and skin, accompanied by the hypnotic dance beat of Air’s “Don’t Be Light (The Hacker Remix).” “Peas” (2003), a three-minute study of a pot of boiling peas in close-up, shot in Tillmans’s former East London studio, depicts the mutual rhythm of the vegetables over audible sounds from a Pentecostal church across the street.

A fifth gallery is dedicated to “Soldiers: The Nineties” (1999), an installation of enlarged newspaper photographs exploring the geopolitical implications of visual culture. Throughout the 1990s, as Cold War tensions eased, the front pages of newspapers often featured images of soldiers engaged in acts of leisure, such as smoking, casually sitting, or playing chess, as thousands of military personnel were deployed to conflict-ridden nations to participate in peacekeeping missions sponsored by the United Nations. Tillmans was intrigued by the erotic undertones of these photographs of anonymous, occasionally bare-chested servicemen, informed by his previous attention to the ways that queer and techno subcultures had adopted camouflage and utility wear. Gallery six explores Tillmans’s work at the threshold of abstraction and representation, as well as his deep interest in the materiality of photographic paper. Tillmans first created a body of work called paper drops after he acquired an industrial-sized printer in 2001 and began experimenting with the optical effects of gravity, which allowed the paper to freely bend and curl. “For me, the photo has always been an object,” Tillmans has said. The manipulated color fields of the “Lighter” (2005- ) works expand upon this dynamic. Made without a camera, the photographic paper is either folded in the darkroom or exposed to evoke the effects of folding, and then framed in plexiglass. The “Silvers” (1992- ) are also cameraless works made by feeding photographic paper through a developer that Tillmans has purposely not cleaned, allowing interferences of dirt and traces of silver salts be visible. Gallery six explores Tillmans’s work at the threshold of abstraction and representation, as well as his deep interest in the materiality of photographic paper. Tillmans first created a body of work called “paper drops” after he acquired an industrial-sized printer in 2001 and began experimenting with the optical effects of gravity, which allowed the paper to freely bend and curl. The manipulated color fields of the Lighter (2005- ) works expand upon this dynamic. Made without a camera, the photographic paper is either folded in the darkroom or exposed to evoke the effects of folding, and then framed in plexiglass. The “Silvers” (1992- ) are also cameraless works made by feeding photographic paper through a developer that Tillmans has purposely not cleaned, allowing interferences of dirt and traces of silver salts be visible. Between 2008 and 2012, Tillmans embarked on a major new project that coincided with his adoption of the digital camera. Comprising portraiture, still life, landscape, street photography, and architectural studies, “Neue Welt” (“New World”) observes the flows of finance, commodities, and people around the world. Alongside these works, gallery seven features documents of social movements that bring to the fore the ethics of care at the heart of Tillmans’s practice. One such exemplary work is a 2014 photograph of dancing figures at one of St. Petersburg’s few gay clubs, the Blue Oyster Bar, taken a year after Vladimir Putin signed a bill outlawing the dissemination of “propaganda for non-traditional sexual relations.” Another notable example is “Black Lives Matter protest, Union Square, b” (2014), depicting an outstretched hand at a Black Lives Matter protest in the wake of widely publicized police killings of African Americans. A highlight of the exhibition is the first US museum presentation of an audiovisual listening room for Tillmans’s first full-length album, “Moon in Earthlight” (2021), a quintessential example of his unique style of “audio photography.” As a musician and documentarian of music, Tillmans has long engaged with music, its cultural significance, and the shared experience of listening: from images of raves, clubs, and dance parties to videos of the artist himself dancing. Produced primarily during the pandemic, the 53- minute album incorporates spoken word, ambient field recordings, and pulsating electronic beats, emphasizing the performative nature of music and its status as a preeminent force that brings people together. The platform just outside the sixth-floor exhibition space will feature Tillmans’s monumental collaboration with Isa Genzken, “Science Fiction / Hier und jetzt zufrieden sein” (2001), a dizzying environment comprised of two irregularly gridded mirrored structures by Genzken and wake, the largest photograph Tillmans has ever made, depicting the aftermath of a party bidding farewell to his London studio. The installation’s title is partially drawn from the German phrase meaning “happy in the here and now,” evoking a contemplative mindfulness as visitors depart the exhibition.

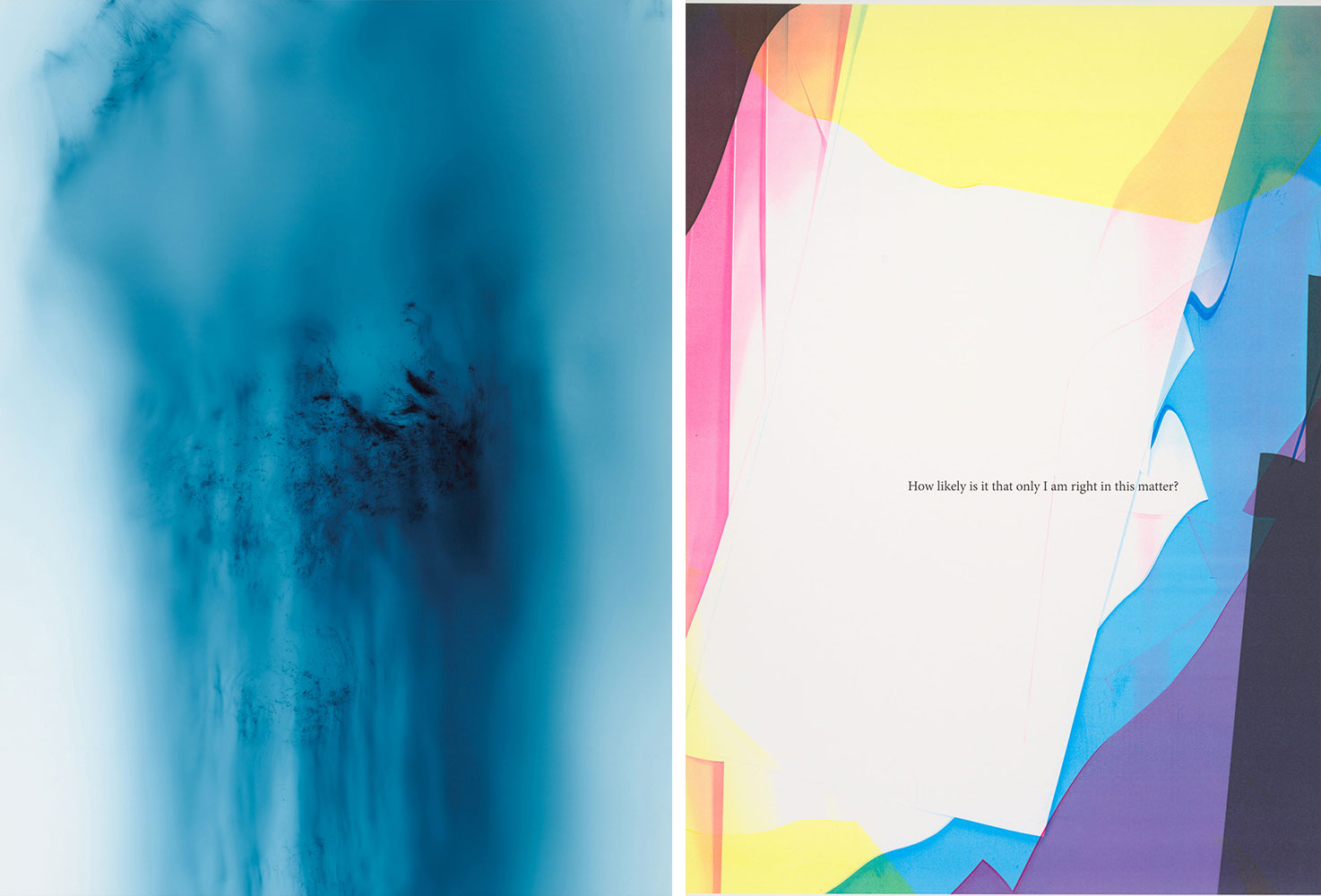

Photo Left: Wolfgang Tillman, Freischwimmer 230 (Free Swimmer 230, 2012). Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London. Right: Wolfgang Tillman, How likely is it that only I am right in this matter? (c) (2018). Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Info: Curator: Roxana Marcoci, Assistant Curators: Caitlin Ryan and Phil Taylor, MoMA, 11 West 53 Street, Manhattan, New York, NY, USA, Duration: 12/9/2022-1/1/2023, Days & Hours: Mon-Fri & Sun 10:30-17:30, Sat 10:30-19:00, https://www.moma.org/

Right: Wolfgang Tillman, Smokin’ Jo (1995). Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Right: Wolfgang Tillman, Icestorm (2001). Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Right: Wolfgang Tillman, Concrete Column III (2021). Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London