ART-PRESENTATION: documenta-Politics and Art

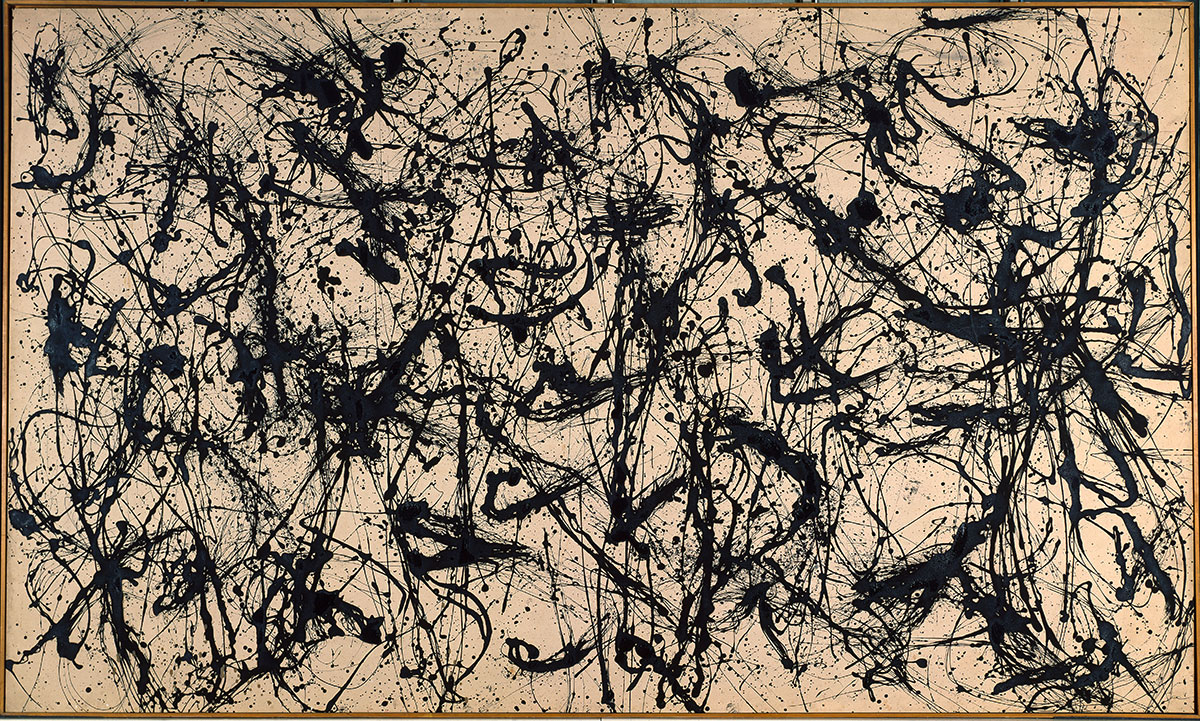

Documenta’s rise to become Germany’s most successful art exhibition was due not least to its political dimension, in particular the need to draw a line under National Socialism, followed by the formation of the Eastern and Western blocs in the Cold War. Although the exhibition claimed to distance itself from Nazi cultural policy, it failed to engage openly with the National Socialist past. At the same time, its politically motivated orientation towards the West led it to reject the socialist concept of art in the Eastern bloc.

Documenta’s rise to become Germany’s most successful art exhibition was due not least to its political dimension, in particular the need to draw a line under National Socialism, followed by the formation of the Eastern and Western blocs in the Cold War. Although the exhibition claimed to distance itself from Nazi cultural policy, it failed to engage openly with the National Socialist past. At the same time, its politically motivated orientation towards the West led it to reject the socialist concept of art in the Eastern bloc.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Deutsches Historisches Museum Archive

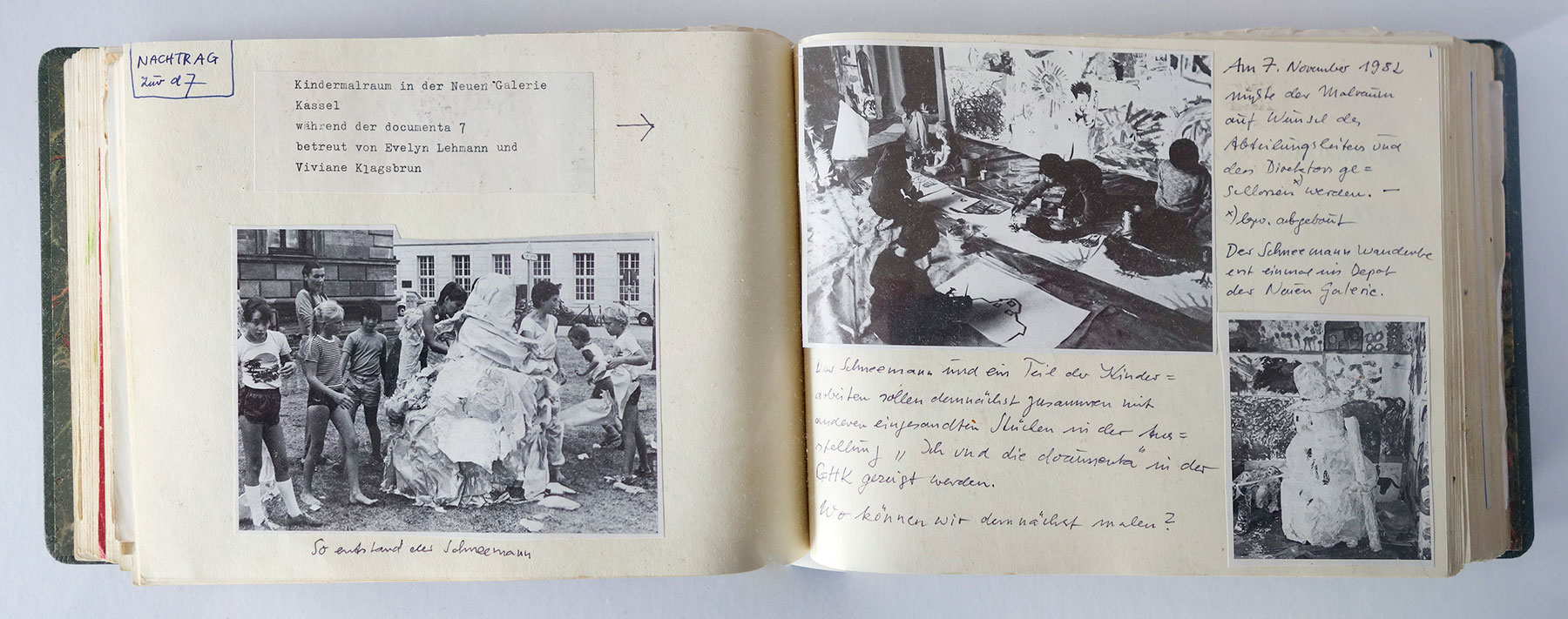

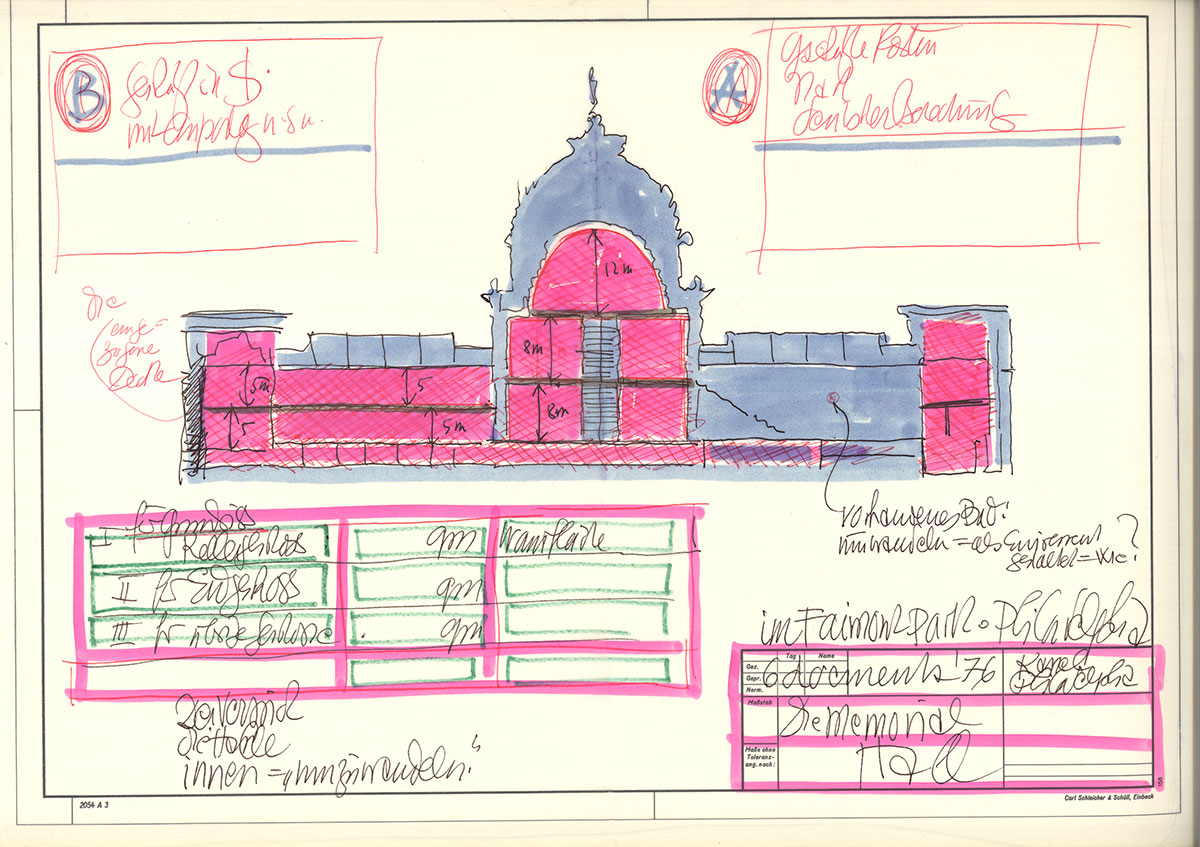

“documenta. Politics and Art” is the first exhibition to focus on documenta as a means of investigating the many-layered interplay of politics and art in German society after 1945. Documenta is one of the most famous and most visited art exhibitions in the world. It was first held in 1955. Since then, the city of Kassel in the state of Hesse has been transformed every four years (later five) into an international beacon of contempo‐rary art. Documenta has always been more than merely a brilliantly staged art show. It helped modernism, which the National Socialists had condemned, to become the young Federal Republic’s favoured epoche and created a welcome distance to the Nazi era. Due to its location near the inner‐German border, documenta was always a political arena in the Cold War. The selection of works of art reflected the alignment with Western Europe and the United States as well as the demarcation from East Ger‐many and the Eastern Bloc. From 1968 onwards, documenta also served as a stage for political protest and art as social criticism. Later, this was often eclipsed by the festival aspect. This exhibition is the first to examine systematically how art was used to pursue broader political goals at documenta during the period from 1955 to 1997.

The Deutsches Historisches Museum looks at the documenta exhibitions of the twentieth century from the first documenta in 1955 to the tenth in 1997. This period saw the consolidation of the Federal Republic, the peak and then the relaxation of Cold War tensions, and the first years after German reunification. The exhibition is structured around a number of themes. This introductory section offers an overview with information on each documenta: the artistic director, the number and origins of the works of art on show, the artists, the budget and the number of visitors. Key data on important political events and social developments set each documenta in its historical context. They also outline the conventions and attitudes prevailing among the people who went to d 1 to d 10 for an encounter with contemporary art.

Documenta did not have an easy start. The financing, above all, long remained un‐certain and the federal grants were only approved a few months before the opening. During tough negotiations, Arnold Bode stuck to his plan. The art professor and designer from Kassel was one of the main visionaries behind the documenta concept. One argument convinced the federal ministers above all: Kassel lay near the inner‐ German border, and documenta would enable art to promote the West as a land of liberty. Federal President Theodor Heuss played an important role. As early as the summer of 1954, the art‐lover declared himself willing to be the patron of the Kassel exhibition. Heuss believed in the power of art to enlighten people. As he put in a speech given a few years earlier: ‘You can’t make culture with politics, but maybe you can make politics with culture’.

The 1955 documenta brought a reappraisal of modernism: the art denounced as ‘de‐generate’ by the National Socialists received official blessing in the Federal Republic. Yet documenta also established continuity with 1933–45, as many of its participants simply resumed their careers. Of the twenty‐one people involved in bringing the first documenta into existence, ten were former Nazis who had been members of the NSDAP, SA, or SS. The fault line ran right through the inmost circle. Arnold Bode, a Social Democrat, and Werner Haftmann, a former member of the National Socialist Party, worked together closely from d1 to d3. Haftmann’s attempt to keep details of his earlier life from becoming known also shaped his judgment of artists. He was not alone in wanting to forget past actions. This exhibition is the first ever to explore in detail the consequences for art history and the politics of memory. Not until d6 in 1977 did a change become evident.

In his plan for the first documenta in 1955, Arnold Bode wrote: “It can become a model for raising consciousness in the world of the European idea in art, 30 kilometres from the zone border”. As a main line of cultural and ideological defence against the East, documenta was conceived as a world stage on which to signal West Germany’s alignment with West‐ern values. With modern art as a symbol of political modernisation, the battle cry was ‘freedom’ as opposed to ‘totalitarianism’ – a term with which the fascism of the recent past was conflated with communism in the present: brown equating with red. Documenta would increasingly become a forum for dissent at which contradictions in society played out in the encounter between the political and the aesthetic.

As a major West German event close to the ‘zone’, documenta presented itself from the start as a bulwark against the Eastern Bloc. In justification, it cited state pressure on artists behind the Iron Curtain to follow the principles of socialist realism. Artistic freedom in the West was set in contrast to a lack of artistic freedom in the East. This led to artists from Eastern European countries and the GDR being assigned a subordinate role at documenta. Only those who had emigrated to the West, or whose styles were compatible with Western concepts of liberty, had their work exhibited. This changed with Chancellor Brandt’s new policy of détente. In 1972, Harald Szeemann tried – and failed – to get Chinese and Russian art to show at documenta 5. The first to succeed was Manfred Schneckenburger, in 1977, who showed work by six socialist realist painters from the GDR at documenta 6. However, this remained a one‐off event. The idea that ‘good’ art was only possible in the freedom of the West prevailed until the 1990s.

The documenta brand stood for a modern, post‐war Germany. The event attracted a steadily increasing number of visitors, mainly reaching a young, educated segment of the public. It developed a sophisticated art education programme and thus created a new, critically aware type of visitor. The attitude of the general public changed over the years, with initial scepticism giving way to relaxed tolerance. Contemporary art, as shown every four to five years at documenta, was receiving ever broader acceptance. The character of documenta became more like that of an entertainment event. Yet it was often accompanied by acts of protest with political and artistic purposes. Basic funding was guaranteed by the city, state and federal authorities. Soon, docu‐menta itself was earning high sums and gaining sponsors who saw benefits in using its image.

Loretta Fahrenholz was invited to create new works for documenta. Politics and Art. She has worked alongside the curatorial team from the complementary viewpoint of artistic research, and in giving the last word to an artist, the writing of documenta’s ongoing history is kept open to new developments and statements. At the documentas to come, ideas of political, market and artistic freedom were interlaced with changing views of the West. During the different stages of the long Cold War, the West was understood variously as political alliances, consumer culture, the capitalist‐imperialist West and – after the fall of the Iron Curtain – the West that had been. The works created by Fahrenholz for this exhibition are the print series “We-Wolf”, the film “documenta Dream” and the performance “A Way of Turning”. “We-Wolf” was made by feeding portrait photos and paintings of artists from the first ten documentas into an image‐recognition programme. The images in the series are haunted by the hidden presences of history as the result of gaps, distortions and the reinterpretation and (mis)reading of data. For “documenta Dream”, Fahrenholz used amateur footage of different documentas as source material for animating a composite historical gaze of visitors to the exhibitions. Finally, in “A Way of Turning”, performers channel documenta’s past by embodying excerpts of happenings and performance pieces that once took place there.

Photo: Second ‘marathon talk’ in Weimar in Preparation for documenta 9, with artistic director Jan Hoet and his predecessors Manfred Schneckenburger, Rudi Fuchs and Harald Szeemann, 13-14 April 1991, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021, photo: Benjamin Katz – New York

Info: Curators: Lars Bang Larsen, Julia Voss, Dorothee Wierling, Research Associate: Alexia Pooth, Artistic Research: Loretta Fahrenholz, The Deutsches Historisches Museum, Pei building, Hinter dem Gießhaus 3, Berlin, Germany, Duration: 18/6/2021-9/1/2022, Days & Hours: Fri-Wed 10:00-18:00, thu 10:00-20:00, www.dhm.de