ART-TRIBUTE:Weaving and other Practices… Alighiero Boetti

We continue our Tribute with, Alighiero Boetti (16/12/1940-24/2/1994). Traveling to Afghanistan at the beginning of the 1970s, he was introduced to the traditional craft of embroidery, which marked a turning point in the artist’s career. His fundamental concern with the relationship between order and disorder is manifest in his grid structures, derived from the magical squares, that feature sayings and aphorisms that stem from cultural, philosophical, mathematical and linguistic contexts.

We continue our Tribute with, Alighiero Boetti (16/12/1940-24/2/1994). Traveling to Afghanistan at the beginning of the 1970s, he was introduced to the traditional craft of embroidery, which marked a turning point in the artist’s career. His fundamental concern with the relationship between order and disorder is manifest in his grid structures, derived from the magical squares, that feature sayings and aphorisms that stem from cultural, philosophical, mathematical and linguistic contexts.

By Dimitris Lempesis

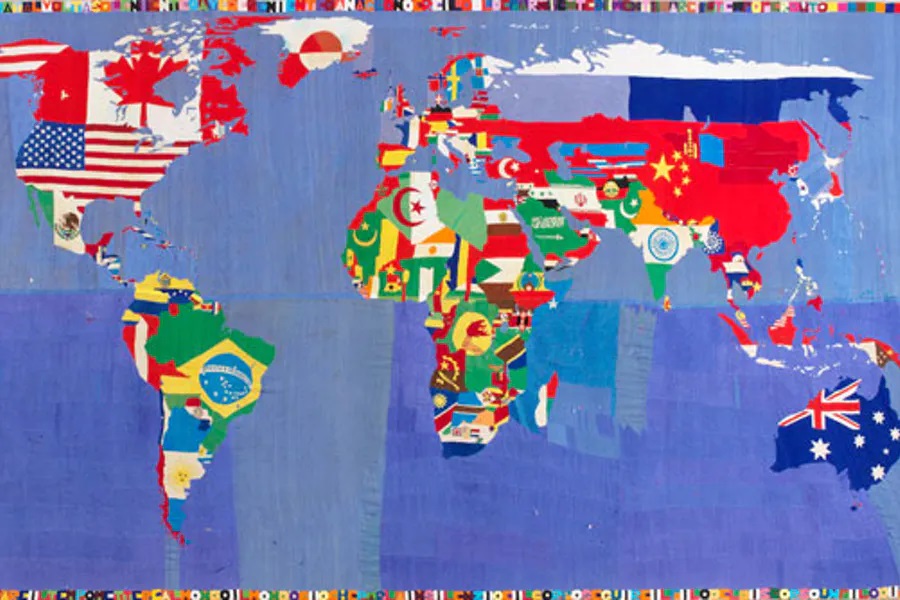

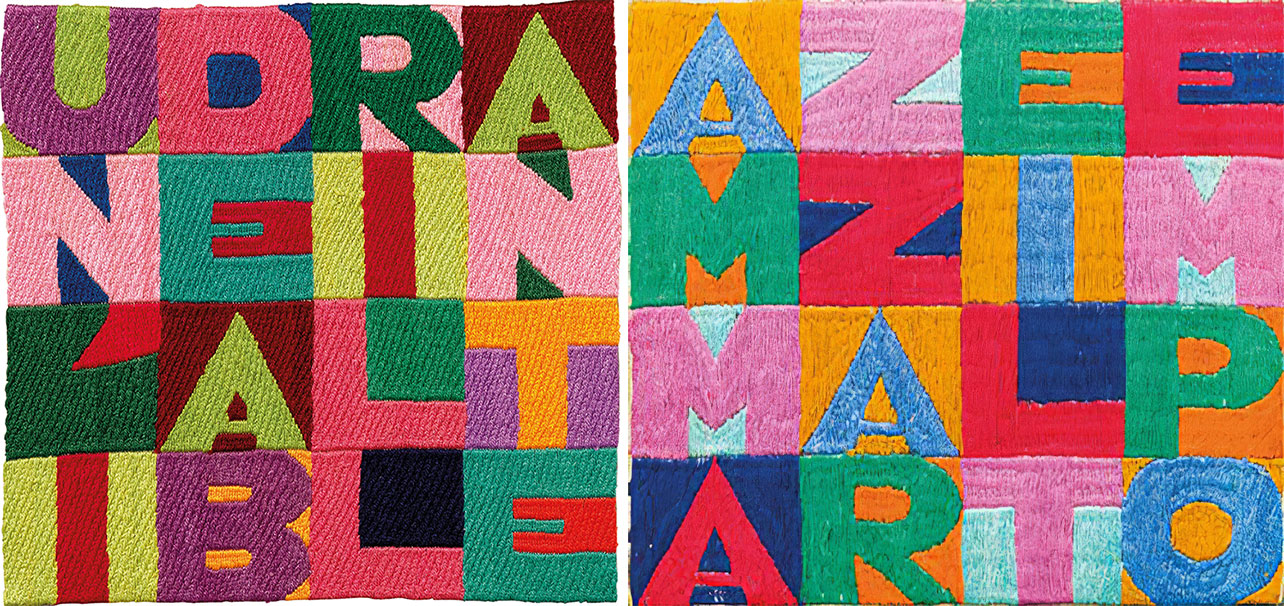

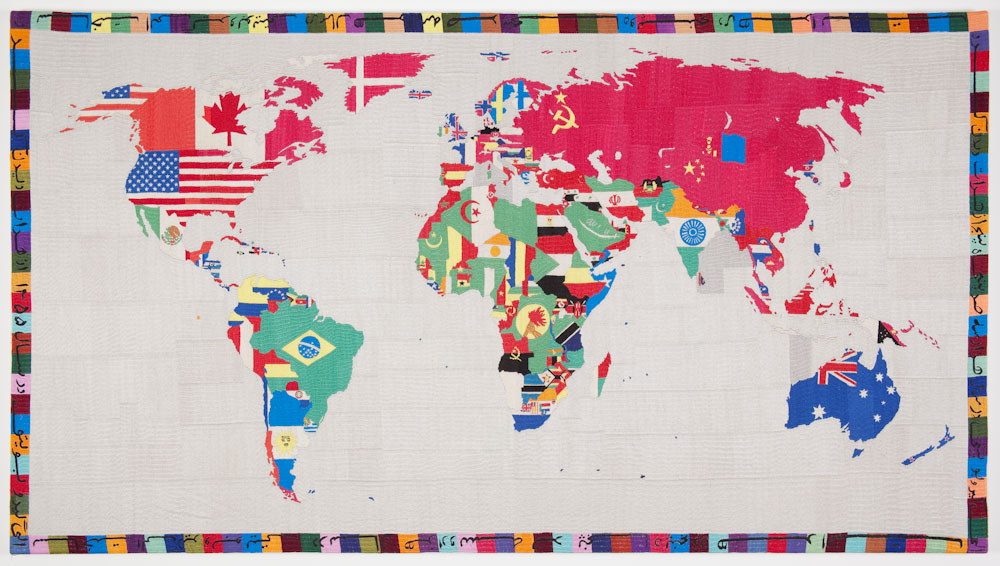

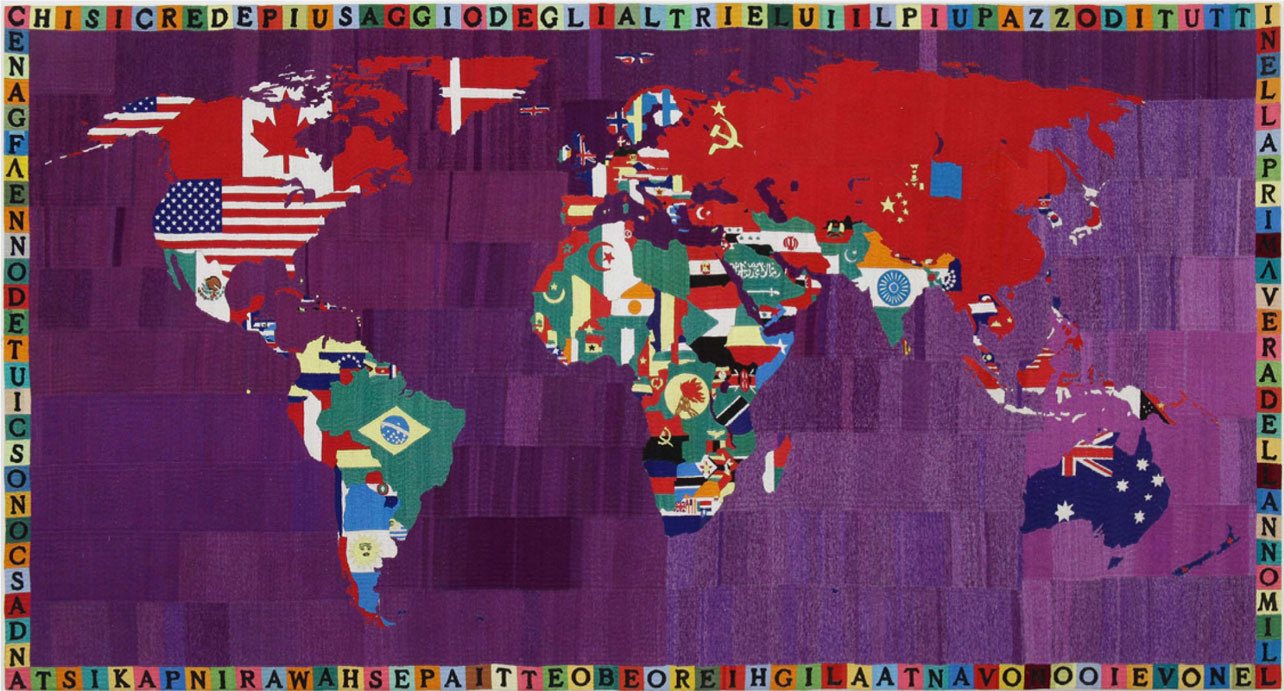

Alighiero Boetti was born in Turin, his artistic career begins in the second half of the ‘60s, when he abandoned his studies at the business school of the University of Turin to work as an artist. Working in his hometown in the early ‘60s amidst a close community of artists that included Luciano Fabro, Mario Merz, Giulio Paolini, and Michelangelo Pistoletto. After his first exhibition in 1967, he becomes associated with the Arte Povera Movement. In 1971 upon his departure from Italy and his arrival in Afghanistan, Alighiero Boetti began a continuous collaboration with local weavers to produce embroidered tapestries, using himself only as the referential artist but considering the works a creation of a combined effort. Mappa del Mundo is a colorful, beautifully crafted tapestry showing each country emblazoned with its own flag, examining borders, frontiers, nationalism, and patriotism. The borders are emblazoned with Italian and Persian texts, selected by Boetti and the craftswomen. Over the next two decades, from 1971 to 1994, more than 150 maps of different colors and sizes were created in this way. From this, geopolitical changes were tracked throughout the world, transforming a simple idea into a political vision by visualizing territory disputes and regime changes. Halfway through their endeavor, the embroiderers selected a pink thread to fill in the oceans, completely altering the look of the works. Boetti loved the intrusion of chance into the artistry of the craftsmen, and let them select the thread colors from then on. Because of this, he has little say in the appearance of the maps. Boetti showed one of his two first embroidery pieces at the section titled “Individual Mythologies “of the 1972 Kassel documenta 51, curated by Harald Szeemann. Up until his premature death in 1987, Boetti was in the process of creating his most complex and biggest tapestry yet, “Tutto” that he devoted his time to depict the world’s cultural diversity. Together with his assistant, Iranian Mahshid Mussari, they collected a wide variety of motif patterns to include in this canvas that is also a representation of the world’s complexity. Sadly, he died without getting to complete this piece. What sets Boetti’s art apart is the importance of his work’s social dimension, his use of mathematical logic, esoteric, different Eastern cultures, the concept of order vs. disorder and finally, his regard of art as a game that draws the audience’s participation in deciphering the writings, the code, and the theme behind each piece.

![]()

![]()