ART-PRESENTATION: Gerhard Richter-Painting After All

Gerhard Richter practices the dual means of representation and abstraction in painting to explore not only the nature of the medium but also its conceptual and historical implications. While these two modes of working are sometimes characterized in oppositional terms, he has famously embraced both, sometimes simultaneously, finding expressive pictorial possibilities in the tension between them. Throughout, he has tested the ability of art to reckon with personal history, collective memory, and identity, particularly in the context of post–World War II German society.

Gerhard Richter practices the dual means of representation and abstraction in painting to explore not only the nature of the medium but also its conceptual and historical implications. While these two modes of working are sometimes characterized in oppositional terms, he has famously embraced both, sometimes simultaneously, finding expressive pictorial possibilities in the tension between them. Throughout, he has tested the ability of art to reckon with personal history, collective memory, and identity, particularly in the context of post–World War II German society.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Met Museum Archive

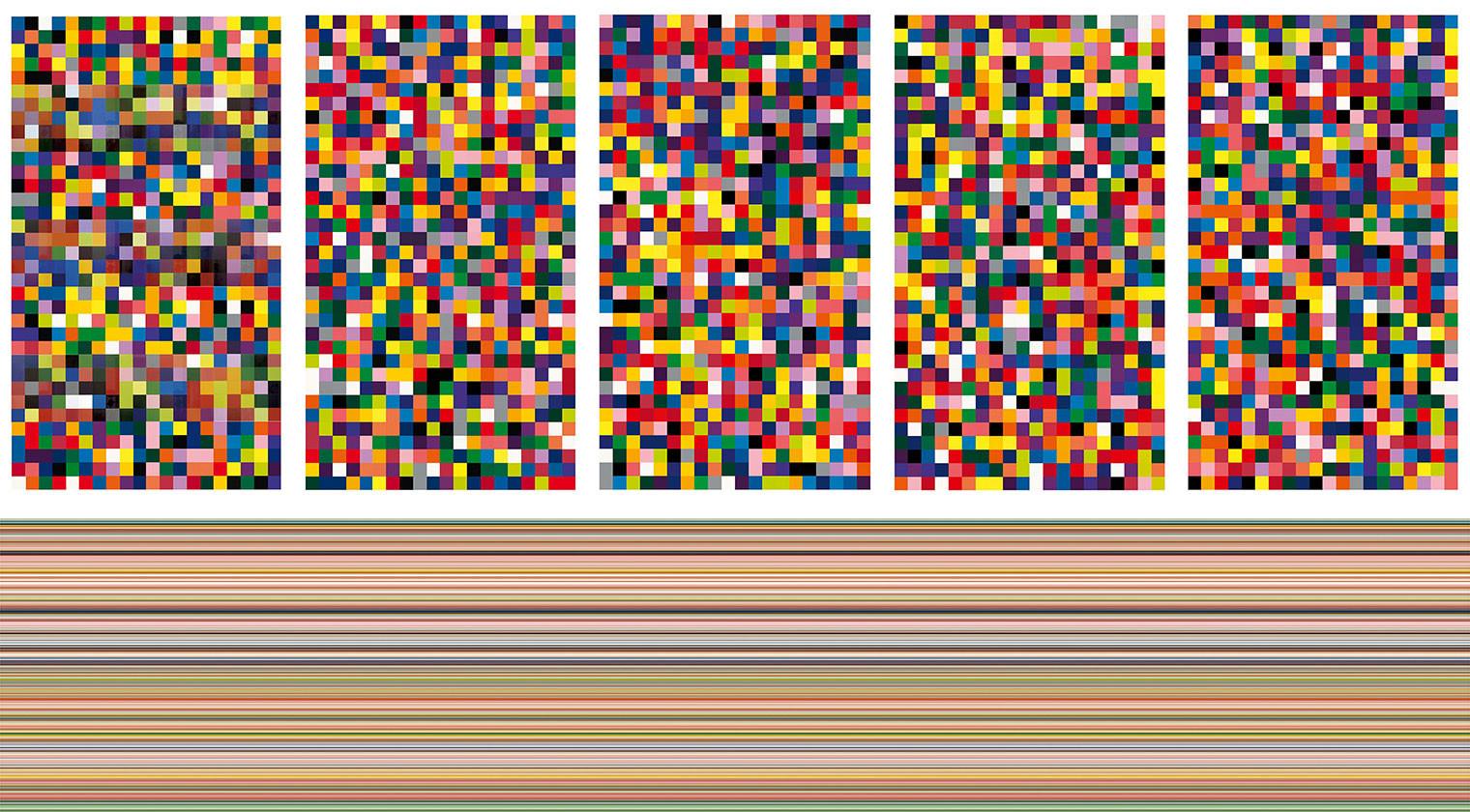

The exhibition “Painting After All” present 100 works that focus on Gerhard Richter’s specific commitment to the medium, as well as his related interests in photography, digital reproduction, and sculpture. Born in 1932 in Dresden, which became part of East Germany following World War II, Gerhard Richter began his career as a mural painter in the Socialist Realist style sanctioned by the German Democratic Republic. He escaped to West Germany in 1961 and considered his subsequent works to be a new start. In his breakthrough years of the mid-1960s, Richter made monochromatic paintings based on images sourced from newspapers, magazines, and family photo albums. Richter was acutely aware of the artistic and cultural context in which he found himself. Some of his so-called photographic paintings perceptively if wryly comment on the banalities of the capitalist society he was encountering for the first time, while others reflect on the darker, at times painfully personal, legacies of Nazism. Responding to postwar Art Movements such as Pop art and Fluxus, Richter transformed seemingly mundane scenes and quotidian snapshots into complex paintings whose meanings are often ambiguous. This sense of indeterminacy is underscored by the blurred surface of the canvases, which confirms and disrupts photography’s claim to “realism” by drawing attention to how paint can assert both an object’s presence and its simultaneous abstraction. Richter’s early works involved the transference of small, seemingly unremarkable black-and-white photographs (found in newspapers, magazines, and family albums) into paintings. His method of rendering the contours of the source material indistinct, either through a blurring of the paint layers or through thick, choppy brushstrokes, highlights the ordinariness of the composition, even as each work is pictorially complex. For Richter, the diffusion of the paintings into gradations of gray made “everything equally important and equally unimportant.” The artist would expand this exploration of the color’s chromatic and ideological neutrality in a series of abstractions that collectively came to be called his “Gray Pictures”. Richter compiled the source imagesfor many of his photo-based paintings into a visual compendium known as the “Atlas”. From the late 1960s onward, photographs of natural landscapes and urban cityscapes predominated in the folios of the “Atlas”, but the artist selected only a few of these for paintings. As Richter explained, “I see countless landscapes, photograph barely 1 in 100,000, and paint barely 1 in 100 of those that I photograph. I am therefore seeking something quite specific; from this I conclude that I know what I want”. Richter’s turn to landscape painting following the tumult of the mid-20th Century in Germany reflects an awareness of how these works both extend and disrupt the Romantic landscape tradition, with its symbolism of the untainted wilderness or the unspoiled countryside. The shift also hints at a defiance in Richter’s approach at a time when many of his contemporaries had proclaimed the death of painting. Unlocking certain conceptual possibilities for his broader practice, these occasional paintings of scenes and vistas punctuate his much larger corpus of abstract works. At once intimate and incisive, Richter’s paintings of family and friends allowed him to explore the possibilities of the portrait as an artistic motif that went beyond the obviously personal. In these figurative paintings, the artist rendered his subjects in distinctive, if sometimes idiosyncratic, compositions that hint at the complexities of particular relationships or artistic collaborations (such as those with Isa Genzken, Gilbert & George, and Brigid Polk), while he also continued to pursue formal and conceptual experimentation. The serial repetition of a subject across multiple canvases or within one composition as in “Six Photos”, either by using the same source image to achieve different, evocative results or by creating a series of related images, is a direct outcome of Richter’s engagement with photography in the making of his pictures. While Richter’s photo-based paintings respond to the traditions of realism, his abstract works engage with 20th Century nonobjective art practices, from gestural Abstraction to Minimalist experiments with the grid. Since the mid-1960s, Abstraction and Figuration have coexisted in Richter’s work. Yet his approach to abstraction has never been static or predictable. The diverse results include his geometrically ordered or algorithmically generated “Color Charts”, brushy, monochromatic fields of paint, and vividly colored, blurry compositions derived from photographic blowups of details from earlier paintings. In the mid-1980s, Richter began to use a method that involved the successive application and removal of layers of paint, primarily by scraping the surfaces of his canvases with a squeegee, augmented with spatters and deliberate brushstrokes. The resulting ruptured surfaces, with their irregular accretions of textures and hues, are like palimpsests that bear traces of what lies beneath. Often produced in series, Richter’s abstractions seem to both challenge and underscore systems of seriality and duplication. Richter has observed that “the forest in general has special significance, perhaps more so in Germany than anywhere else. You can lose your way in forests, feel deserted, but also secure, held fast in the bosom of the undergrowth. A fine romantic subject”.

Yet even as he acknowledges the powerful persistence of its romance, the artist evokes the woods as a place of ambiguity, haunted by darker seductions and mysteries. In the abstract series “Wald” (forest), while the associations seem impressionisticthe paintings articulate both the personal experience of a particular place and a collective signification of the forest. Ominously recalling the beechwood trees (Buchenwald) and birch groves (Birkenau) that gave the areas around notorious Nazi concentration camps their names, this cycle of twelve paintings from 2005 foreshadows Richter’s turn to one of those sites as a subject in 2014. The simultaneous occurrence of figuration and abstraction in Richter’s body of work has sometimes been confounding to viewers and critics, but for the artist the distinction is less salient. Rather, his art is marked by a dual commitment to and ambivalence about painting, as both a historical and a personal medium. Accordingly, Richter’s practice evinces many artistic departures and returns, in which he formulated particular systems of working and then consciously transformed or abandoned them, all informed by an acute understanding of pictorial traditions and coupled with a rigorous critical assessment of his own work. In Richter’s paintings, intimate and expansive spaces can thus coexist. In recent years Richter has focused his attention on abstraction. His artistic techniques, however, continue to evolve: alongside compositions made with oils and squeegees on canvas, he investigates the potential of the painterly medium in this era of digital technology. For works such as “Strip” he used computers to effect a complicated process of distillation and division to create an image. Indeed Richter’s long-standing interest in iterative and replicative processes through the production of facsimiles, prints, and editions, as well as the use of photographs of earlier paintings as the basis for later ones, have a conceptual affinity to his transformation of painting through algorithmic means. Chance procedures, infinitely differentiated constellations of color, and an expansive size drawing upon the scale of political murals and Hollywood screens were among the foundational paradigms of Abstract Expressionist painting. Their immense impact on postwar Europe reached Richter after his move from East to West Germany in 1961. The “Cage” paintings, one of his most important series of large-scale abstractions, integrate yet invert all three of these features, situating them in a present where the humanistic aspirations originally associated with them have no more relevance. Richter defines abstraction in these works as a mode of perpetual cancellation or even destruction of gestures, formerly understood as expressing intentions and dispositions. The title pays tribute to a key promoter of chance aesthetics, John Cage, whose radical participatory concepts exerted a strong pull on both American artists and—as these paintings evidence—some Europeans as well. Their mural-like scale notwithstanding, these sizeable squares convey the spatial confinement of seemingly infinite erasures of gesture and color. Thus “Cage” might just name the contemporary subject’s extremely limited conditions of experience. The final installation in the exhibition, the “Birkenau” cycle, consists of 4 paintings, their 4 partitioned digital copies, and 4 photographs secretly taken in the death camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau by a member of the Sonderkommando (a group of mainly Jewish prisoners forced to dispose of victims of the gas chamber). In 2014 Richter returned to these photographs (which had preoccupied him since the 1950s) after encountering Georges Didi-Huberman’s study “Images in Spite of All” (2008), and he engaged once more with the question of whether and how a German artist could (or could not) address the history of the Holocaust. After a yearlong attempt to render the photographic images, the artist gradually veiled his original figurative drawings on the 4 canvases through layers of paint, in a slow and hesitant process of applying and then scouring each coat with a squeegee to produce the heavily disturbed, abstract surfaces. This distinctive facture and a subdued palette distinguish the “Birkenau” paintings from the chromatic and textural opulence of Richter’s other cycles, such as “Cages” and “Wald”. These features make evident his conscious struggle to address through painting the documents of historical trauma while curtailing the inevitable spectacular nature of the reproduced image. In a further gesture to limit the fetishistic singularity of the image, Richter produced digital duplicates of the paintings, thereby subverting their unique import and mirroring their effect. The multiplicative action positions the series as not only a commemoration of the most horrendous genocide in the twentieth century and its particular historical and cultural magnitude, but also a critical reflection on the grave possibility that such crimes against humanity could reoccur.

Info: Curators: Sheena Wagstaff and Benjamin H. D. Buchloh with Brinda Kumar, The Met Breuer, 945 Madison Avenue, New York, Duration: 4/3-5/7/20, Days & Hours: Tue-Thu & Sun 10:00-17:30, Fri-Sat 10:00-21:00, www.metmuseum.org

Right: Gerhard Richter, Uncle Rudi, 1965. Oil on canvas, 87 x 49.5 cm, Památník Lidice, © Gerhard Richter, Courtesy the artist and the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Down: Gerhard Richter, Strip, 2013. Inkjet print on fine art paper between acrylic and aluminum, 200 x 1000 cm, Private Collection, © Gerhard Richter, Courtesy the artist and the Metropolitan Museum of Art